An ode to autumn – is October the finest month of all?

October is the fading of the sun reflected in the fiery leaves, it is the changing of the seasons, and David Barnett loves it

October, then; the month on which the year pivots, off-centre, off-kilter, like the axis of the Earth. Hopes of an Indian summer lie fallow in the fields, winter is coming but not just yet, merely sending its heralds in on the chill bite in the rising winds.

October is the house on the borderland, one foot in the dying embers of evening sun and one foot in the grave. It is the month when night’s veil is drawn down earlier, when by the methodical witchcraft of time we gain an hour on the last Sunday of the month.

It is the month of apples and pumpkins and turnips and leaves – of course of leaves – shaking off their cool green to reveal that their fiery hues that have lurked unseen all through summer.

“I’m so glad I live in a world where there are Octobers,” said Anne in LM Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, and so am I, for it is surely the finest month of all.

But why the name October, which is more reminiscent of the number eight, when this is the 10th month of the year? For that we must blame the Romans, and their penchant for well-rounded things in multiples of ten. The ancient Roman calendar had 10 months, of course, and October was the eighth. It wasn’t until the end of the 1st century BC that Julius Caesar reformed the calendar and what we now know as January and February were inserted at the beginning of the year, this Julian calendar – later modified in the 16th century by Pope Gregory to space the leap years and get us the 365.3435 days a year – is pretty much what we use today.

So October is the tenth month, masquerading in its remembrance of being the eighth, surely a more temperate month, which is why we sometimes get the tantalising memory of the warmth of summer on mischievous October breezes.

October is also the month of death, Halloween, of course, and its pagan predecessor Samhain. The entire month’s 31 days are a preparation for Día de los Muertos, the Mexican Day of the Dead, which falls at the beginning of November, when the veil between the world of the living and the dead is at its most fragile and thin. October is the beginning of the death of the year, the Ragnarok of our progression through the seasons. And it is the trees that pull on their widow’s weeds first, though not the black of mourning, but the fiery hues of celebration, just as the Day of the Dead is not a sombre affair but a joyous re-connection with our departed loved ones.

Why do the leaves on the trees change colour in autumn? They don’t. They are merely revealing the shades of red, orange and yellow that they have hidden under a green coat since spring.

Like most growing things, trees use photosynthesis to grow and thrive. They turn the light of the sun into sugar, powered by water and nutrients from the soil, their leaves like a vast array of solar panels to capture the honeyed sunshine. The driving force for photosynthesis is chlorophyll, which is the pigment that gives the leaves their green colour.

Come October, when the sunshine starts to wane and the days get shorter, the trees shut down their photosynthesising processes and prepare to sleep for the winter. They stop renewing the chlorophyll in their leaves, and the green drains away, with the other chemicals in the leaves pushing through to dominance. Flavanols, which are yellow, and carotenoids, which are orange. Anthocyanins, resplendent in reds and purples. The green is a memory of summer, the hues that speak of bonfires and warm hearths now resurgent until spring.

It is not just the leaves that change colour in October. Look up, on a clear night, and observe the Moon. This month’s full Moon falls on 9 October, and it is always a special one. This is the Hunter’s Moon, or the Blood Moon. Its name dates back to Indigenous Americans, who would use the light of the Moon to track and kill the deer to stockpile food for the winter. It is the full Moon of death, but death to give life in the harsh winter.

“Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall,” wrote F Scott Fitzgerald inThe Great Gatsby. Jack Kerouac said in On The Road: “I was going home in October. Everybody goes home in October.” It is a time to retreat into our homes, to light the fires, to stock the pantry with apples and to bring the harvest in, to pile high the deer we hunted by the light of the Blood Moon. To wait out the shortening days until the end of the month, when time itself changes.

At 2am on the morning of 30 October, the last Sunday of the month, the clocks fall back. It is a rare kind of magic to watch this in the digital age, the clocks ticking over in unison from 01.59 to… 01.00. It is as if we have gained that hour of our lives back (though we know we will surrender it again come spring). It is as if that dark, quiet hour between 1am and 2am is suddenly erased, wiped from the record. Does anything you do in that hour count? Is it a mad, wild, lost hour where secrets can be whispered and ghosts may visit? Every year in October we time-travel, skipping back an hour, perhaps giving us a chance to make things right.

We change the clocks twice a year because of Benjamin Franklin, the American politician and inventor, who wrote in 1784 while visiting France that Parisians should be woken an hour earlier in summer by church bell and cannon, to make the most of the sunlight.

It wasn’t for more than a century that the idea would be seriously considered, when a New Zealand scientist called George Vernon Hudson took the suggestion even further, saying the clocks should go forward by two hours. There was little appetite for it, and the idea was bounced around for a while — including by British builder William Willett, who campaigned for clocks to be changed so there could be more light in the evenings for his golf playing. A curious aside — Willet is the ancestor of Coldplay’s Chris Martin, who late wrote a song called “Clocks”.

But it was war that propelled the idea of the clock changes into reality, when the German army turned their clocks forward in spring 1916 to take advantage of the earlier daylight, and the rest of Europe followed suit.

The hour we stole from March, we get back in October. We have a 25-hour day in October, always around Halloween, that time when the walls between worlds are crumbled and the doors that have been sealed shut all year creak open a little. Who comes through in that extra hour? What peers around the door? What stories are forged in that 60 minutes that should not be?

Halloween is plastic cauldrons and witch hats and hollowed-out pumpkins. It is brash and commercial and hated by many, though they are not the sort of people we wish to spend time with

October is the storyteller’s month. It lends itself to gathering around the fire and spinning yarns, telling tall tales, pondering what is out there in the dark… and here with us among the jumping shadows cast by fire and candle and lamp.

Writers find solace in the embers of October, the stories that have percolated in their minds emerging like the reds and yellows of the leaves, their words flowing onto the page by the light of the Blood Moon.

Kerouac was particularly Octoberish, born in New England, where leaf-peepers gather to watch the glorious canopy of the trees embrace autumn, and dying in the month, in 1969, on the 21st day.

His novel Doctor Sax evokes his childhood in the town of Lowell, where “In the fall there were great sere brown sidefields sloping down to the Merrimac all rich with broken pines and browns.” He later wrote of that childhood in the Book of Dreams, the 1960 fragments of his night-drenched thoughts, that it was “where figures stalk cleanly and sharp in soft gloom clouds…”

And of course, John Keats, whose paean to the finest month, “To Autumn”, celebrates the “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness”. Where are the songs of spring, asks Keats? Forget them, for autumn “hast thy music too”. “Hedge-crickets since, and now with treble soft, the red-breast whistles from a garden croft, and gathering swallows twitter in the skies.”

Neil Gaiman, in his 2006 short story collection Fragile Things, presented us with “October In The Chair”, in which the months gather in the woods and tell each other tales. “October was in the chair,” he wrote, “so it was chilly that evening, and the leaves were red and orange and tumbled from the trees that circled the grove”.

“October In The Chair” is a homage to, and was written for, Ray Bradbury, the writer who was truly the King of October, his finery a crown of fiery leaves and his mantle sewn from the darkest night.

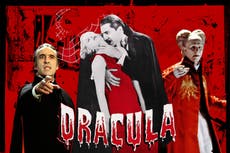

Bradbury, who died in 2012, was the American author who embraced October and Halloween in short stories and novels, who is synonymous with the month and season through the tales collected in The October Country and The Halloween Tree, and his magnum opus of the spooky month, Something Wicked This Way Comes.

Two boys, Will Halloway and Jim Nightshade, become embroiled in the witchery of October when Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show rolls into their small town. It is a slim novel that contains all the multitudes of October and growing up, and growing old. Anticipation and fear of the future, in the pitch-black of autumn nights, and friendship, and love, and family, and terror.

Bradbury loved Halloween, and so do we. We love Halloween in all its guises, in the faces it presents to us like the aspects of the Fates, the three-in-one. We love the young, modern, slick celebration, we love the older, nostalgic, warmth of childhood Halloweens, we love the crone mother’s knowing, toothless smile that speaks of the holiday’s dark origins.

Halloween is plastic cauldrons and witch hats and hollowed-out pumpkins. It is brash and commercial and hated by many, though they are not the sort of people we wish to spend time with. Halloween is not a new thing, nor an American import. Ask anyone who, as a child, put in the hours disembowelling a rock-hard turnip in the 1970s. Halloween is jump-scares and horror films and witches and ghosts. It is the shrill shrieks of children in the street, it is too much chocolate and too many sweets, it is dressing up and laughing with a look over our shoulder, in the hope our merriment will ward off evil spirits and welcome home those we have lost.

A friend calls the time between Halloween and Bonfire Night, “Dark Week”, and maintains there should be a public holiday over those seven days, for those of us who truly embrace the dark, delicious thrills of October.

And before Halloween, Samhain. A celebration lost in the mists of time, pagan and Celtic and Neolithic. An end to harvest, a preparation for winter. Song and fire and the fermented juice of the fruits of the forest and field, bacchanalian and lusty, the time-lost festival of the dead and the living, rolling over from what we now know as Halloween and into The Day of the Dead.

October is the fading of the sun reflected in the fiery leaves turning on the trees, it is the change of the seasons, it is ghosts and scares and fond memories of those we have lost.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks