Why are we so obsessed with the multiverse right now?

We seem particularly fascinated by the concept of the multiverse at the moment, perhaps it’s because this reality sometimes seems just so awful, writes David Barnett

The idea that there are infinite variations of this world is both an enticing and terrifying consideration. On the one hand, there may be a version of reality where you are in fact reading this on your luxury yacht moored off St Tropez with a glass of champagne in hand and your butler standing attentively to one side ready to serve your every need, you having won the Euromillions last month. Or there may be one where that twist of fate that caused your parents to meet never happened, perhaps by dint of a cancelled train or sudden emergency, and you were never actually born and aren’t reading this at all.

We’re talking about the multiverse, the concept that there are infinite dimensions that cater to every single possibility that could ever have possibly existed. In one universe, perhaps, there was a devastating nuclear war in 1986 and the versions of us that survived are scrabbling in the ruins for food. In another, the dinosaurs were never wiped out and remain the dominant form of life on Earth. In yet another, life is exactly the same as it is in this world except Bucks Fizz never won the Eurovision Song Contest.

We seem particularly fascinated by the concept of the multiverse at the moment, with various strands of popular culture investigating through different media this evergreen idea.

Front and centre is, of course, the latest Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) escapade, Dr Strange and the Multiverse of Madness. The Marvel universe in comics has for decades posited a string of almost-identical Earths strung out through the cosmos like pearls, with the world where most of the Marvel action taking designated Earth-616. DC did similar in their comics as well, going back to the 1960s and used as a pragmatic device to explain away some of the discrepancies in the continuity of characters that came into the DC stable but had already been around for decades… if something in, say, Wonder Woman’s history didn’t quite fit into the attempt to bring DC’s superheroes into a coherent timeline, it could be explained away as having happened on another Earth.

In the latest Dr Strange movie, the titular Sorcerer Supreme meets up with a pan-dimensional refugee, America Chavez, and together they stomp through the multiverse with abandon. For Marvel, importing the idea of the multiverse from the comics to the movies is a masterstroke that solves an issue that has been bugging fans since the MCU was created.

Some of Marvel’s biggest properties had already been farmed out to other production companies before the MCU gained its foothold at the top of the superhero movie tree, such as Spider-Man, the X-Men and the Fantastic Four. We’ve already seen in the movies how what were in effect completely different cinematic universes have now been folded into the MCU by dint of the multiverse, which means anything can happen anywhere so all they have to do is bring them to the Marvel Earth by way of interdimensional gateway shenanigans.

As much as moviegoers might think they did, though, Marvel by no means invented the idea of the multiverse, it’s actually been both a concept in fiction and a consideration for science for a long time.

Thus, in another universe there might not be a different version of you, but rather everyone might have a Stylophone for a head

And especially now. Take the current indie movie hit Everything Everywhere All at Once written and directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert and starring Michelle Yeoh as an embattled laundrette owner who is given the ability to “verse-jump” and experiences a number of alternate realities where the old maxim that nothing is certain except death and taxes seems to hold true across the multiverse.

Kwan and Scheinert admit that the success of the Marvel blockbusters such as Dr Strange and Spider-Man: No Way Home paved the way for the success of their movie, softening audiences up to the idea of the multiverse. They told the Radio Times last month: “The audience is tuned into it ... They are now prepared for this version of the film, of the multiverse concept, which is kind of meant to show how inherently problematic the multiverse is for narrative – you know, once the characters’ decisions get watered down by every other universe, the character gets watered down, nothing matters. That was something we wanted to explore, and I don't think we would have been able to capture as many audience members if it wasn’t for those movies.”

But there is also the idea that things are so uniformly awful in many respects in this world, that we as consumers of culture are quite open to the rather seductive idea that there are other worlds almost exactly like ours where things might be better… or, somehow satisfyingly, even worse.

Scheinert told the Radio Times: “I was like, ‘okay, great. Let's make a movie that’s nihilistic and acknowledges that!’ Then it just kind of bounced back and forth until we’re like, ‘oh, the multiverse is the perfect metaphor for what it feels like to live right now.’ If we can explore all of our neuroses and fears through the multiverse, maybe we can learn something about ourselves. And so that was it, we’re just chasing questions when we’re making movies – we don't know the answers until we show it in front of an audience sometimes.”

This year has also seen the BBC TV adaptation of Kate Atkinson’s 2013 novel Life After Life, which attempts to answer the question many of us have surely considered at some point: what if you could have your time again? Would you do things differently?

In Life After Life, Ursula Todd (Thomasin McKenzie), born into the early 20th century, enters into a seemingly endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth, with each new incarnation having residual memories of her previous existence, allowing her to change the course of her life in sometimes subtle, sometimes huge ways.

This isn’t overtly a multiverse story, because, unlike the two big movies, there is no shifting between different dimensions; it’s simply the same story told over and over again with different outcomes. But the science of the multiverse tells us that this has to be a multiverse story. Ursula isn’t simply erasing what has gone before and replacing it with a new version; that old version already exists and cannot be wiped. So she is creating a new reality, a new version of her life, that runs concurrently with all the others.

There are really two main schools of thought on multiverses, or at least there are in this world. One is known as the “cosmological multiverse”, and suggests that when the universe was created in the Big Bang, it all happened so quickly and with so much energy that when the universe started to rapidly expand there were quantum fluctuations that created separate universes which also started to expand and through their own expansion caused yet more to come into existence, and on and on and on… This idea came from Russian physicist Andrei Linde, who said that this could account for an infinite number of universes that developed, really, in a completely different way to ours. Thus, in another universe there might not be a different version of you, but rather everyone might have a Stylophone for a head, or it might be ruled by dogs with laser eyes. Stuff like that.

The other multiverse idea is a bit closer to the one most commonly presented in fiction and also has a pleasing pop-cultural crossover as well. The idea of the “quantum universe” suggests that the universe is constantly splitting into other versions of reality, thanks to every single decision we make. With 7 billion people on Earth making decisions every second of every day, that’s a lot of parallel worlds out there, potentially ranging from ones where Donald Trump woke up one morning and thought, “Hey, today I’ll nuke North Korea!” to ones where you had Pop-Tarts for breakfast instead of porridge.

The quantum multiverse theory was the work of Hugh Everett III, an American physicist who posited his “Many Worlds Theory” in 1958. It was roundly dismissed by the scientific community at the time, and Everett died in 1972, aged just 51. He never saw science eventually come round to his thinking and begin to treat his theories seriously. He did, however, leave another legacy.

His son, Mark Oliver Everett, grew up to be the lead singer of American band Eels. It was Mark, aged just 19, who found his father’s body when he’d died of a heart attack in bed. The two men barely knew each other, Everett’s work kept him estranged from his own children. But decades later, Mark went on a journey of self-discovery about his father and himself, producing in 2008 and documentary that was shown on the BBC, Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives, about his relationship with his father, and his father’s work.

Science fiction has usually been the genre that has embraced the Many Worlds Theory most joyously, but more mainstream books and cinema have also flirted with it, sometimes subtly, sometimes more overtly.

Take the 1998 movie Sliding Doors, for example, where the simple act of missing a Tube train causes the life of Gwyneth Paltrow’s character to split into dual narratives, one where she catches her philandering boyfriend in bed with another woman and leaves to begin a romance with John Hannah, and one where she doesn’t, leaving her trudging through life unfulfilled.

No matter how many infinite worlds there are out there, no matter how many versions of you, living different lives, you and me, we’re stuck in this one, where each decision we make impacts this reality

In a way, all fiction is multiverse fiction. Even that which cleaves most closely to the life we are familiar with. Even Coronation Street and EastEnders are multiverse stories. We see these characters, we recognise them as people we could know or live next door to. And yet, they don’t exist. Albert Square is not a real place, nor is Weatherfield, as familiar as they look. These stories, these lives, never happened. Each episode of a soap is essentially a window into a parallel universe almost exactly like our own. The same with every single novel, in which people who do not exist in our world do things in worlds almost precisely like our own, but the very act of them being there and doing those things and having those thoughts creates a whole separate reality.

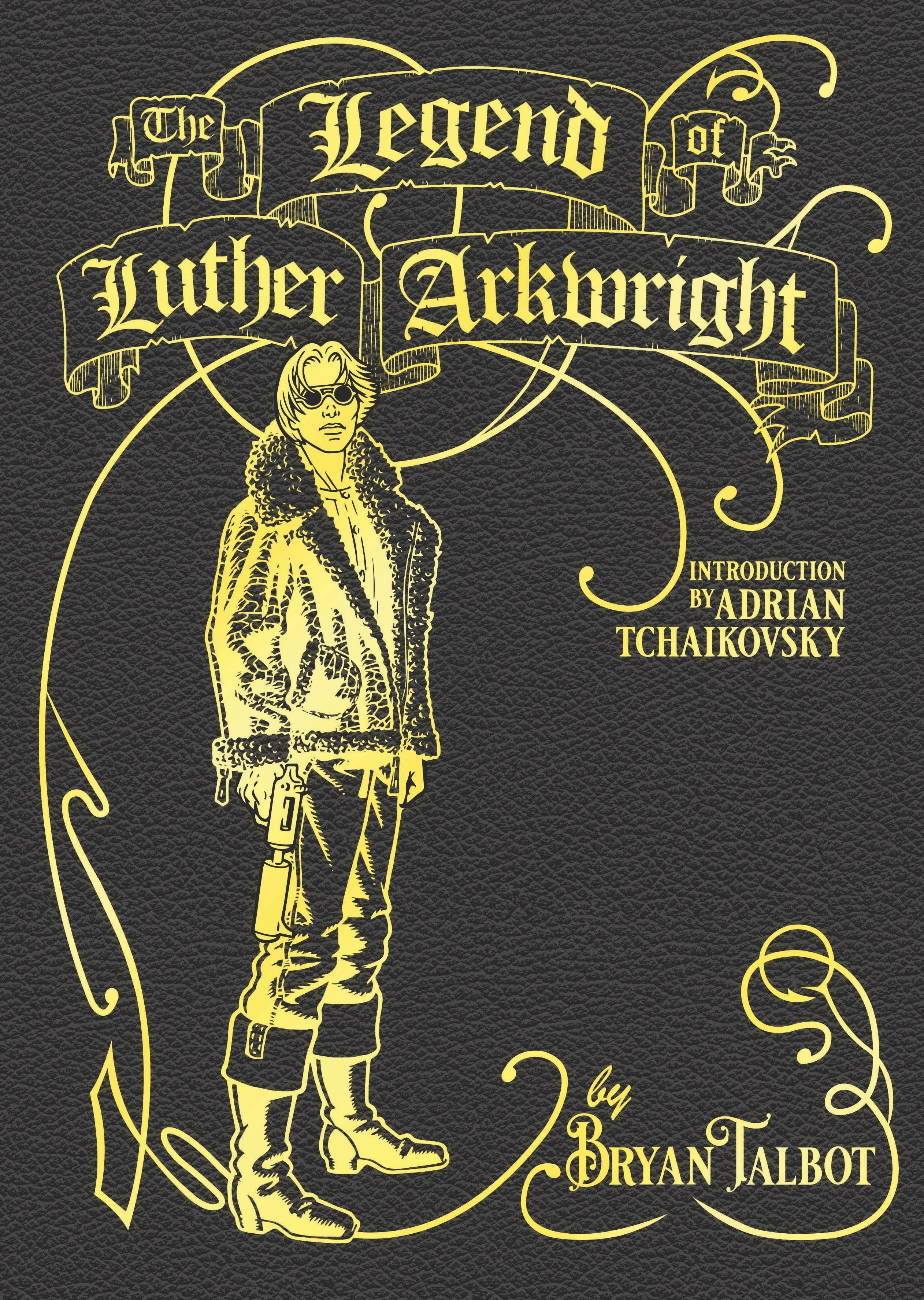

On 14 July there is published a big graphic novel entitled The Legend of Luther Arkwright, written and drawn by the legendary British comics creator Bryan Talbot, who was born in Wigan, lived in Preston and now lives in Sunderland, with his wife Mary, also a graphic novelist of note whose kind-of memoir Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes was the first graphic novel to with the Costa Book Award for biography.

Talbot’s character, Luther Arkwright, is part secret agent, part anarchist rabble-rouser, who has the ability to travel between parallel worlds, acting on behalf of a seemingly-utopian reality known as “Zero-Zero”, ostensibly to save the many and varied worlds from diverse destruction.

Talbot first debuted Luther Arkwright in 1978, and this latest magnum opus is the first outing for the character for 20 years, since the last instalment, Heart of Empire.

“The idea of a multiverse, of alternate realities, parallel worlds, has been around a long time, especially in science fiction,” says Talbot. “It allows us to answer that question that’s at the heart of a lot of fiction: what if…? What if instead of this thing happening, something else happened instead? Would life be different? Would the world be different?

“It’s something that far predates the Marvel version, of course. There have always been books that look at how the world would look if a major event did or didn’t take place. Kingsley Amis wrote The Alteration in the 1970s, in which the Reformation didn’t happen. And Len Deighton wrote SSGB, about what would have happened if the Nazis had won the Second World War and occupied Britain.”

Talbot was inspired to create Luther Arkwright through being a fan of the work of British author Michael Moorcock, who is credited with coining the term multiverse. Moorcock has written a huge body of interconnected works featuring a diverse range of fantasy and science fictional characters, such as Elric of Melnibone, Hawkmoon, Corum and Jerry Cornelius. The stories could and often are read alone and in isolation, except for one thing; each of these characters is an aspect of what Moorcock calls The Eternal Champion, different in each universe but essentially the same.

Most inspirational to Talbot was Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius, a 60s hipster whose picaresque adventures are mainly chronicled in a quartet of novels written in the 1960s and 1970s: The Final Programme, A Cure for Cancer, The English Assassin and The Condition of Muzak.

“Cornelius was very psychedelic, very counter-cultural and it immediately chimed with me,” says Talbot, “and I knew I wanted to do something similar with Luther Arkwright, but different.

“Moorcock’s characters don’t really travel across the different dimensions as such, and I wanted Arkwright to be able to do that. Quantum mechanics has an infinite number of universes possible, but I needed to keep that more manageable.”

The idea that there are agents such as Luther Arkwright travelling between different alternate realities is strangely comforting, as though there are emissaries from worlds that are worse and better than our own who can show us the error of our ways and stop things spiralling out of control before its too late.

However, that, of course, is fiction. No matter how many infinite worlds there are out there, no matter how many versions of you, living different lives, you and me, we’re stuck in this one, where each decision we make impacts this reality, and this reality alone, no matter how many spin-off worlds it births.

So the decisions we make here, we’re kind of stuck with. Which begs the question: what are you going to have for breakfast?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks