Dracula at 125: How a nobleman vampire got his fangs into the world

Count Dracula is one of the most recognised figures in literature around the world. On the novel’s 125th anniversary, David Barnett asks what it is about Bram Stoker’s story that captures people’s imaginations

Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula isn’t really that explicit about the motivation behind the undead Transylvanian nobleman’s journey to England, which forms the bulk of the book.

It’s hardly a spoiler to say that the plucky band led by Abraham Van Helsing eventually foil whatever plans Count Dracula had, be they merely to dine well in London, the centre of the Victorian world, or to spread the plague of vampirism across Britain.

But 125 years after Dublin-born Stoker published his novel, on 26 May 1897, his character has indeed achieved the kind of viral domination that any self-respecting vampire would drool at.

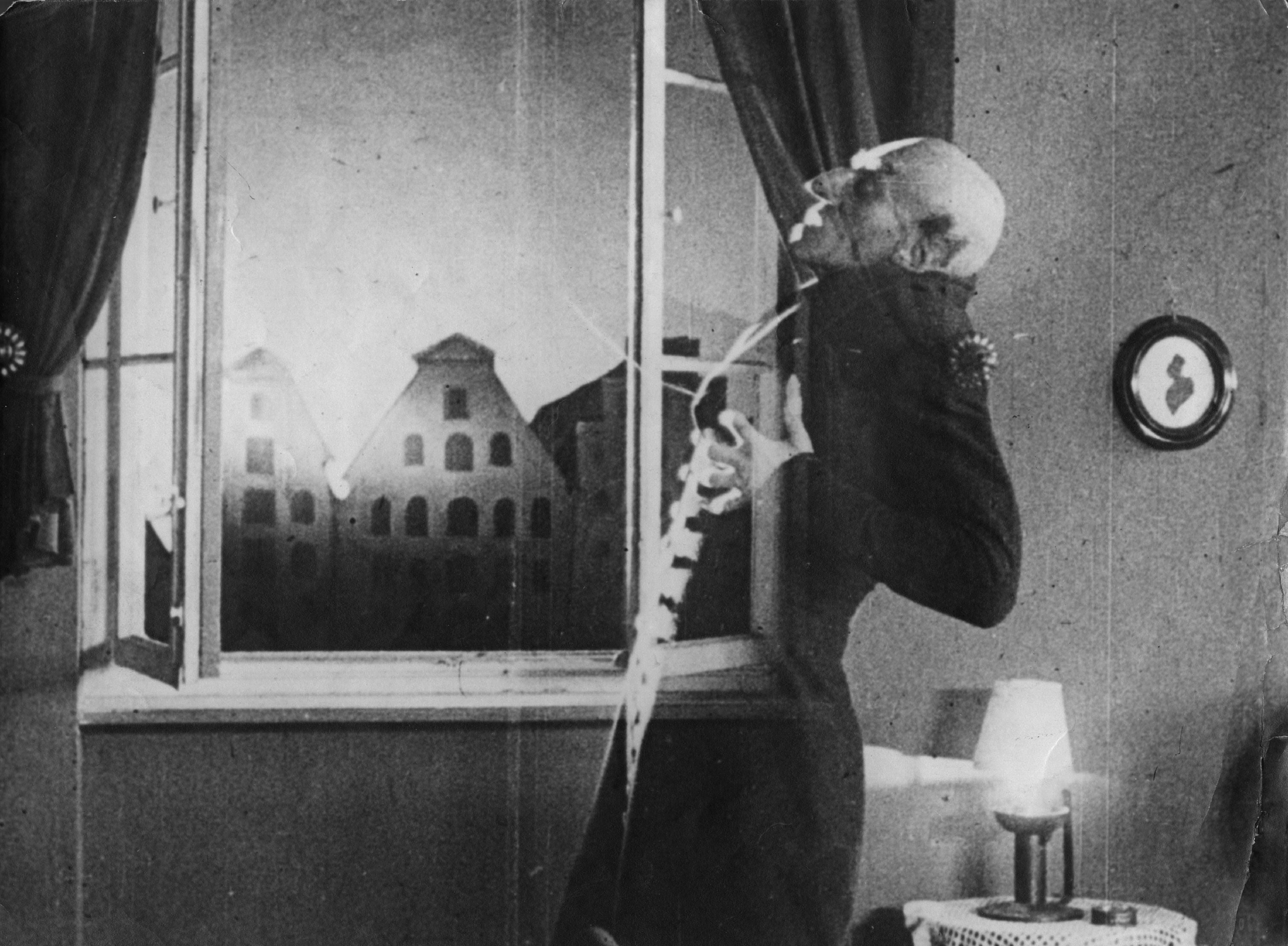

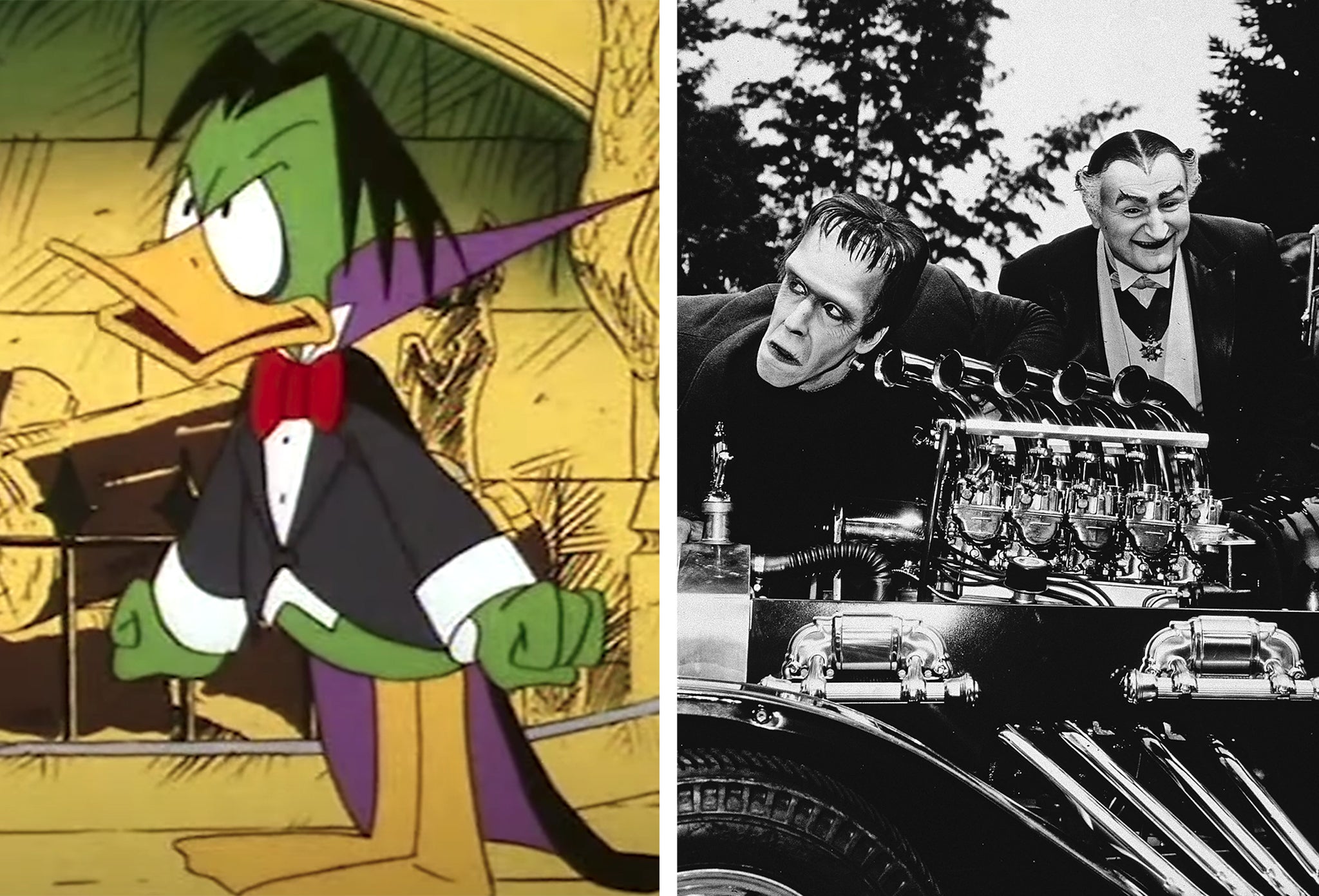

Are there many people who haven’t heard the name Dracula? And who hasen’t seen at least one movie, be it FW Murnau’s 1922 adaptation Nosferatu, or one of the Universal monster flicks in the 1930s, in which Count Dracula evolved from the horrific, otherworldly imp of the Murnau silent movie to the dapper, charmingly sinister European nobleman of Bela Lugosi? Or perhaps your first introduction to Count Dracula was Christopher Lee’s lean, blood-eyed predator from the sometimes-schlocky Hammer Studios movies that ran from the late 1950s to the 1970s. Maybe even 1992’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, in which Gary Oldman’s vampire smoulders with sensuality in pursuit of Winona Ryder’s repressed Mina Harker.

But Count Dracula isn’t just confined to literature and cinema. He is, and has been, everywhere, as ubiquitous and widespread as the bats and rats of which he is sometimes formed. He’s in the deathly purple pallor of Sesame Street’s The Count, teaching children their numbers in an Eastern European accent, fangs distended. He’s in the old Walls lolly, beloved of children on seaside bucket and spade holidays, black ice like the wily count’s cape hiding blood-red ice cream inside. What child in the early 1980s didn’t thirst for the I Vant To Bite Your Finger board game, in which players had to insert a digit into the mouth of a cardboard Dracula and see if he “bit” them and left two felt-tip pin-pricks behind?

Dracula has appeared in comic books, notably a run in his own title from Marvel Comics in the 1970s, he’s been in countless TV adaptations, including Mark Gatiss’s 2020 series that updates the story to shocking and satisfying effect. He’s been repackaged for children in Scooby-Doo and Count Duckula and The Munsters. He’s appeared in video games and on trading cards and in any medium you care to think of it. There can’t be many in the western world who don’t recognise Count Dracula. His cultural colonisation is almost all-consuming.

Dracula, it is fair to say, is in the blood.

It was in the blood of Stoker as well, long before he actually sat down and put pen to paper to write it. Born in 1847, Stoker grew up in the coastal town of Clontarf, just outside Dublin, and relocated to London in 1878 to become the business manager at the Lyceum Theatre.

He later became the manager of the Victorian stage star Sir Henry Irving, and moved in theatrical circles, all the while nursing ambitions to write. One day in March 1890 he scribbled a sudden thought down on a scrap of paper in barely legible handwriting:

Young man goes out — sees girls one tries — to kiss him not on the lips but the throat. Old Count interferes — rage and fury diabolical. This man belongs to me and I want him.

Anyone who has read Dracula, or seen one of the many film adaptations, will instantly recognise that as one of the pivotal scenes, where young solicitor Jonathan Harker, having journeyed to Dracula’s foreboding castle in the Transylvanian mountains to finalise the Count’s property purchasing deals in London, almost falls victim to Dracula’s coterie of vampiric women.

If that fragmented dream-note scribbled down in March 1890 was the impetus for Dracula, it was Stoker’s holiday to the North Yorkshire seaside town of Whitby in July of that year where his famous story really began to take form and substance. Stoker is thought to have visited alone for a week at the end of July but returned a week later, with Florence and 11-year-old Noel in tow. According to the Whitby Gazette, which scrupulously recorded all comings and goings of out-of-towners, the Stokers stayed at number 6 Royal Crescent, on the town’s West Cliff, which overlooks the grey, cold Atlantic and mirrors the headland at the other side of the harbour, on which crouches the imposing ruins of Whitby Abbey and the church of St Mary, with its graveyard assailed by salty sea-winds.

Stoker was something of a voracious magpie of a writer, plucking bits from history and legend and assembling them all into a coherent shape

Whitby, of course, was to be a great inspiration to Stoker. He immersed himself in the seaside town, visiting the museums and libraries and wandering among the weather-worn headstones of St Mary’s. He engaged fishermen and mariners for their tales of the sea. One old salt told Stoker of the Dmitry, a Russian schooner that had run full-tilt into the town’s Tate Hill Pier, sails up, on a storm-lashed day five years before.

Slowly, the puzzle of Dracula was solving itself in his mind. Stoker was something of a voracious magpie of a writer, plucking bits from history and legend and assembling them all into a coherent shape. He is said to have met with Armin Vambery, a Hungarian writer who told him wild tales of his adventures in the inhospitable Carpathian Mountains. He is thought to have borrowed the name of his titular vampiric count from Vlad III Dracula, or Vlad the Impaler, the 15th-century ruler of Wallachia, a medieval territory in Romania.

The true story of the Dmitry became, in Stoker’s hands, the terrible tale of the Demeter, which also crashed into the same stone pier at Whitby, but, in this narrative, the crew were all dead, drained of blood, and its cargo coffins filled with good Transylvanian earth. Its only surviving passenger was a midnight-black dog that leapt from the stricken ship and ran up the 199 steps that lead to the Abbey, where it would transform back into the undead Dracula.

Dracula is an epistolary novel, told in letters and journal entries. After Jonathan Harker’s encounter with Dracula in Transylvania, the action shifts to Whitby, where his fiance, Mina Harker, is holidaying, with her friend Lucy Westenra. Their vacation coincides with Dracula arriving on British shores, and after Lucy falls victim to the Count’s vampiric advances, her three prospective suitors — Dr John Seward, Quincey Morris, and Arthur Holmewood — bring in Seward’s former teacher Abraham Van Helsing to investigate. After Lucy’s death — and rising as one of the undead — the group hunts Dracula, even as the vampire targets Mina, and then follow him to Transylvania, where they meet up with Jonathan to despatch the villainous undead nobleman.

Today, Whitby is a popular bucket and spade tourist resort on the North Yorkshire coast, its front lined with raucous amusement arcades and fish and chip shops. On one corner lurks a fortune teller in a booth behind a beaded curtain, and just a little way past her is the Dracula Experience, a dark, tight labyrinth where students don plastic fangs and loom out of the blackness to make holidaymakers shriek.

If you go up to West Cliff, beyond the whale bones that form an arch, you can stand outside the Royal Hotel and look across at the ruined Abbey and St Mary’s Church, exactly the same view that Stoker would have seen in 1890 as he ruminated on his developing story.

The town is a hotchpotch of family holidays, history and Dracula, and no one knows it better than Harry Collett, who runs Dracula-themed walks around Whitby, dressed in the top hat and Victorian garb that has earned him the name The Man In Black.

I met Collett, who has been doing night-time guided walks for 30 years, a few years ago, and he told me, “Whitby was undoubtedly instrumental to Stoker when he wrote Dracula. When he took up residency in Royal Crescent, his landlady would turf him out in the morning so she could clean the room. Stoker would go to the reading room of the Royal Hotel and look out at the scene you can see now. That first week when he was alone in Whitby, he would go around, soaking up the ambiance.

“Dracula runs ashore as a black dog. This is based on another legend Stoker would have heard about a dark hound – a story brought over by the Vikings. And the black coach that later takes Jonathan Harker to Castle Dracula was taken from a local story about the lord of Mulgrave Castle, who used to take to a black coach that rattled down the road when he was on his way to court Elizabeth Cholmeley.”

Stoker’s novel was an instant hit when it was published in 1897, attracting very favourable reviews and comparisons to such luminaries as Wilkie Collins, author of The Woman in White, and the pioneer of Gothic fiction, Ann Radcliffe.

Stoker had lived through the Jack the Ripper killings, remember, and he had a feel for what would be terrifying to people at that time

With his newfound authorial success, Stoker began to work as a journalist for the Daily Telegraph in London, reigniting a career began when he worked on his hometown paper, the Dublin Evening Mail, which was co-owned by the writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, whose novel Carmilla was one of the earliest vampire novels.

Thanks to his writing, his journalism and his theatre work, Stoker counted among his friends the American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, fellow novelist Arthur Conan Doyle, and even Oscar Wilde, who was something of a love rival to the Dracula writer. Wilde had apparently proposed to Florence Balcombe, but she had turned him down in favour of Stoker, prompting something of a long-running feud between the two men, who had met at Trinity College in Dublin.

By the turn of the 20th century, the name of Dracula was becoming recognisable across the world, as was that of its creator, Bram Stoker. In fact, the two became synonymous, as a young boy called Dacre found out in 1970.

Growing up in Montreal, Canada, where Halloween was just as big a deal as in the neighbouring United States, revellers dressed as vampires would routinely visit Dacre’s house on their trick or treat route. And they would employ extra relish when they knocked at the family home, bellowing, “please don’t drink our blood!”

Aged about 12, Dacre went to see his father after one such visit, perplexed at the reaction their home always elicited. His father then went to get a book from the shelf, a first edition of Dracula, signed by the author and dedicated to the grandmother of Dacre Stoker, who then discovered he was in face the great-grand-nephew of the creator of one of the most enduring literary characters in history.

“To be honest, it wasn’t until much later that I really delved into my connection to Bram, when I was at university,” says Dacre, who now lives in South Carolina. “And when I did, I wanted to find out everything, what this man was all about.”

Dacre is now something of a leading authority on Bram Stoker and Dracula, and over the years has unearthed correspondence, notes and photographs. In 2009, working from his ancestor’s notes, he co-authored with screenwriter Ian Holt a sequel novel, Dracula the Un-dead, and three years ago wrote a prequel, with JD Barker, called Dracul, which has been optioned for film.

Dacre says that Dracula came at exactly the right time. There was a huge upsweep in interest in the occult and paranormal during the late Victorian period, and Stoker’s masterstroke was giving his novel a contemporary setting. This wasn’t some Gothic romance set centuries before, it was happening here and now in the bustling metropolis of end of the century London, centre of the newly industrialised world.

“It made the story more edgy, scarier to people,” says Dacre. “Stoker had lived through the Jack the Ripper killings, remember, and he had a feel for what would be terrifying to people at that time. And people were asking questions about what came after death. There was a lot of interest in spiritualism and people were wondering, what comes after this?”

Dacre agrees that Dracula’s reach has become all-consuming. “It’s difficult to actually think of a medium into which it hasn’t been adapted in some form,” he says. “And a significant moment came in 1962, when Oxford University declared the book a classic, which gave it its proper place in literary history.”

This week, Dacre will be visiting the UK, including a trip to Whitby, where he is spending a few days and attending a celebratory dinner in honour of his great-grand-uncle. Then he’s up to Scotland to visit Cruden Bay, a location that is as important to Dracula as Whitby, though gets less press.

The Stokers were regular visitors to Cruden Bay and it’s thought Stoker wrote the final chapters of his book while staying there at the Kilmarnock Arms Hotel in 1896. Nearby Slains Castle is thought to have been the inspiration for Castle Dracula in Transylvania. Dacre will be officially unveiling a plaque that shows the Dracula-relevant locations around the area.

“What I want to do is keep Bram Stoker’s legacy alive,” says Dacre, “to allow people to go to these places that inspired Dracula, and to tell people about the stories behind what became one of the most famous books in the world.”

It’s a fair bet that Dracula, and his creator Bram Stoker, will not be forgotten any time soon. A century after FW Murnau’s first celluloid outing for the book with Nosferatu, an upcoming movie will retell the story through the eyes of the vampire’s slavish servant Renfield.

Dracula was published in 1897, which was the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria. The book marks its 125th anniversary just a few days ahead of Queen Elizabeth II’s platinum jubilee. The charming yet deadly Transylvanian nobleman continues to spread his influence as empires rise and all, as monarchs come and go. Now quiet, and listen to them, the children of the night. What music they make.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks