The writer who found inspiration in the folklore tale of the Treacle Walker

Alan Garner speaks to David Barnett about his Booker Prize longlisted novel and how he discovered the Treacle Walker, a person who can heal anything but jealousy

It’s the question every author dreads: “where do you get your ideas?” Yet, it was the query that set Alan Garner on the road almost a decade ago to his latest work of fiction, Treacle Walker, published this week.

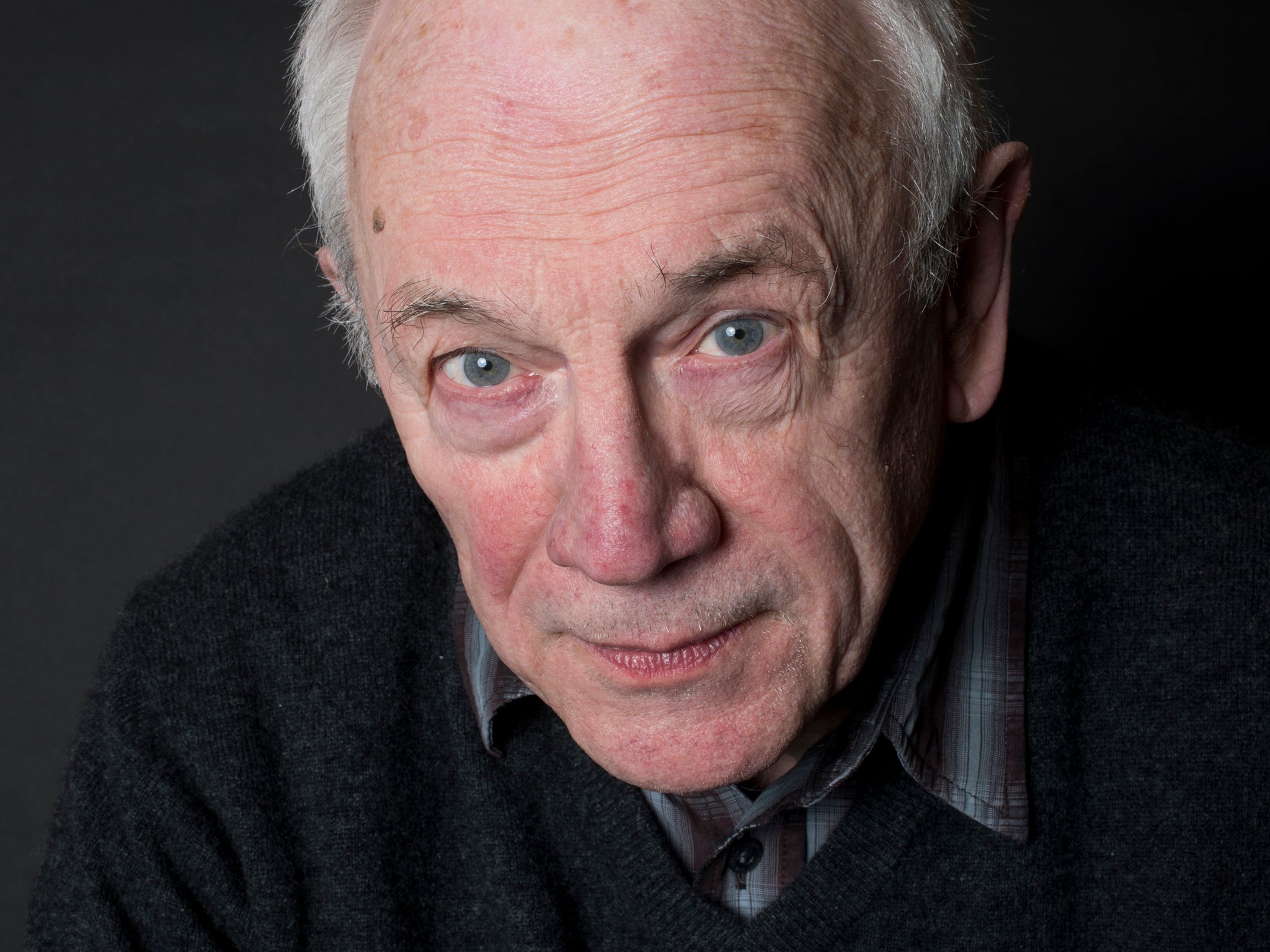

Garner had a birthday this month – “Ah, 87, wind-turned age,” he says, quoting Dylan Thomas, when I wish him the best at the start of our Zoom call. Garner has excellent recall; he quotes chunks of his own books at me throughout the interview, despite claiming that “once a thing’s finished I tend to forget it; if you want to talk about The Weirdstone of Brisingamen you’ll have me at a disadvantage, but Treacle Walker is still in my head.”

Weirdstone was Garner’s first novel, published in 1960. Ostensibly a fantasy novel for children, it told the tale of Colin and Susan, who are staying with family friends in Garner’s native Alderley Edge, Cheshire, and get drawn into an ages-old battle between the forces of darkness, led by the wizard Nastrond, and the good magician Cadellin Silverbrow. It spawned two sequels: 1963’s The Moon of Gomrath, and – after quite a gap – the concluding part of the trilogy, Boneland, in 2012.

Aside from his memoir Where Shall We Run To? (which was published in 2018), Boneland was his most recent novel and it was the very same year of publication that he was given the idea for what would become Treacle Walker. It was a project which began with that dreaded question, “where do you get your ideas?”

“It was 20 July 2012,” says Garner, from his home, a medieval cottage in Blackden, a few miles out of Alderley Edge. “I was walking across an Iron Age hill fort in Huddersfield, called Castle hill, with a friend, Bob Cywinski, who is a professor of physics at Huddersfield University. The night before, we’d spent most of the evening failing to communicate because he’s a scientist and no matter how imaginative science is, they have to start with something, even if it’s to say, ‘right, I’m looking at this, even if I don’t know what it is’.

“Bob had been pursuing me in the question all authors get: where do you find your ideas? And I had not succeeded in getting across to him a successful answer. I’d got as far as saying, I don’t find them, they find me, which made it only worse for Bob.”

That July day Cywinski took Garner to see the Iron Age fort, and while they were walking, it was the turn of the scientist to tell the writer a story, this one about a tramp called Arthur Helliwell, who Cywinski never knew, but his mother did.

“Helliwell was what is known as a local tramp,” said Garner. “He didn’t just wander, he worked a circuit of the farms on the moors of the Pennines and he did odd jobs and was allowed to kip in a barn. He was of pure working class, uneducated origins, but he went by another name. Treacle Walker. And he was a healer, and said he could heal anything except jealousy.”

The intellect which we need and which I prize quite highly, is a drudge. It’s a superb editor but it can’t have an original idea

That lines makes it into Garner’s book of the same name. In it, young Joe lives alone in a ramshackle house, his days spent exploring the local landscape, reading his Knockout comics and marking time by the lone steam train that whistles by every noon. Into his life comes Treacle Walker, a rag and bone man who gives Joe a donkey stone – used for whitewashing steps – and a half-empty jar of ointment, in exchange for Joe’s old pyjamas and a lamb’s bone. This sets Joe off on a journey of discovering that his small world is a lot stranger than he realises, now he knows how to look at it properly.

Cywinski’s story had given Garner what he calls “morning sickness”, when an idea takes root in his fertile mind and there’s the scent of a new book on the wind. “I said to Bob, do you remember the conversation we had last night about ideas?” Garner recalls. “Well, look at your watch and remember the time, because you’ve just given me a book. Well, that made him blink. He said, ‘what’s it about?’ I said, ‘I have no idea. I just know it’s a book.’”

This wasn’t enough for Cywinski, whose scientific, rational mind demanded more than Garner’s vague feeling that there was a book on the horizon. Garner says: “In the end I said to him, ‘here’s something I think you’ll understand. You know how Einstein and others got their ideas? They saw the answer and had to find out the question,’ and he got that immediately because it’s very common among creative scientists. They see the answer and ask, well, what’s the question?”

Garner had his answer. Now he just had to find out who Treacle Walker was, and what he meant, and how this was going to be his next book.

The more Garner thought about Treacle Walker, the more the questions started to form. And being immersed in folklore and the lost language of these isles, he knew something his scientist friend didn’t: treacle didn’t just mean, as Cywinski responded when Garner asked him what it was, “the sticky stuff”. It meant healing. “There’s a treacle well in Alice in Wonderland,” he said, “and Lewis Carroll got that from Binsey, just outside Oxford, where there is a treacle well, which is a holy well.”

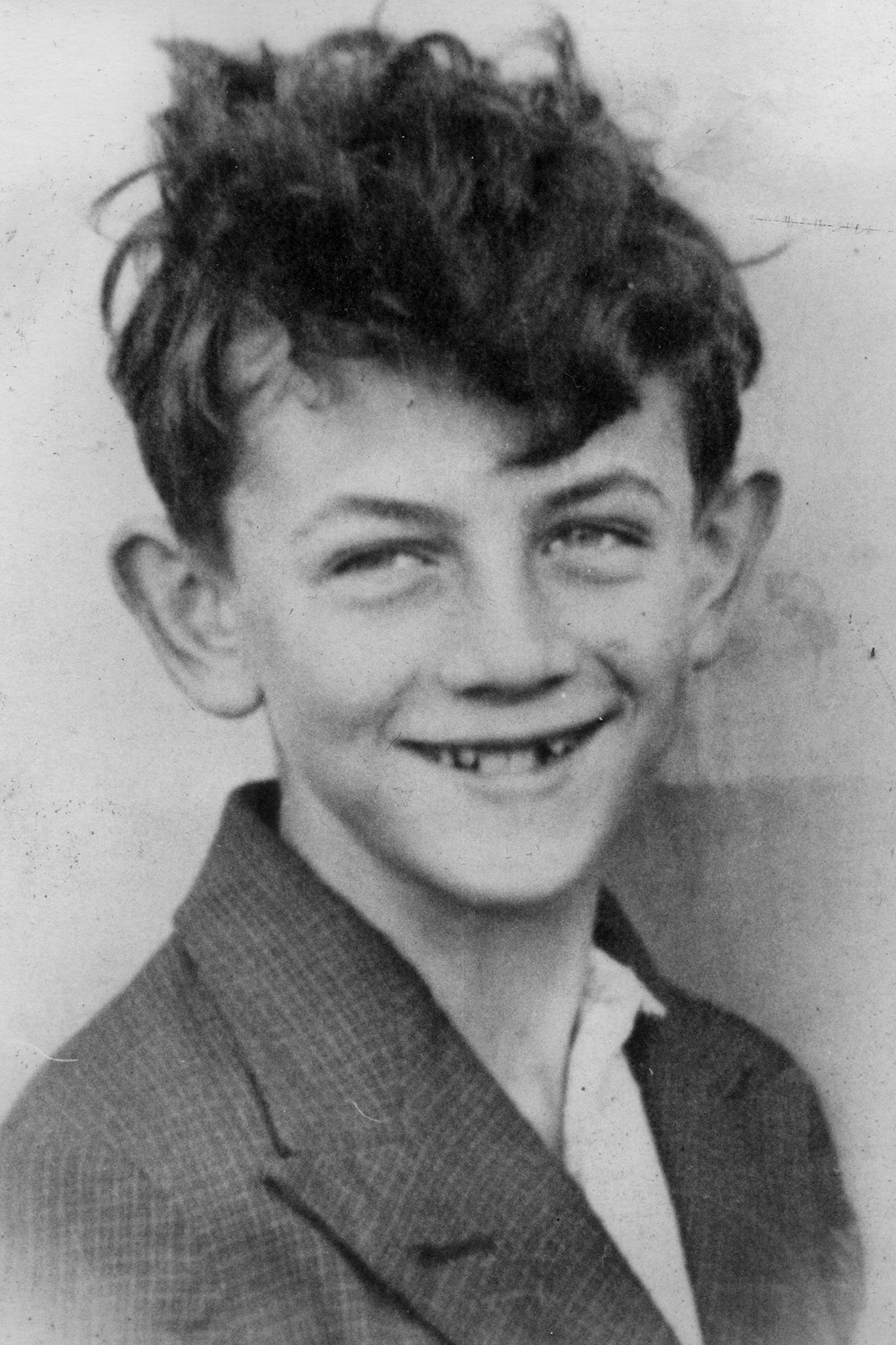

Alan Garner was born in 1934 in Congleton, Cheshire, and soon moved to Alderley Edge with what he calls his “rural, working class family”. He suffered a series of serious illnesses as a child, and says he was declared dead three times. His education was at the village school and on what locals called The Edge, where he learned to love and respect the folklore and history of the place.

He won a scholarship to Manchester Grammar School and then on to Magdelen College, Oxford, to study classics, the first of his family to receive formal education at that level. His grandfather, he recalled, could read and write, but didn’t. However, he gave the young Garner an education which money couldn’t buy, and tutored him in the ways and stories of The Edge.

In his mid-fifties, Garner was diagnosed as bipolar. “I’m sort of a split personality,” he told me, “because the writer in me is totally intuitive but I went through a very rigorous academic education in Latin and Greek and philosophy, and so I learned quite early on through the agonies of writing the Weirdstone that that kind of brain can’t write. The intellect which we need and which I prize quite highly, is a drudge. It’s a superb editor but it can’t have an original idea. That comes from somewhere else, and I’m no wiser about that.”

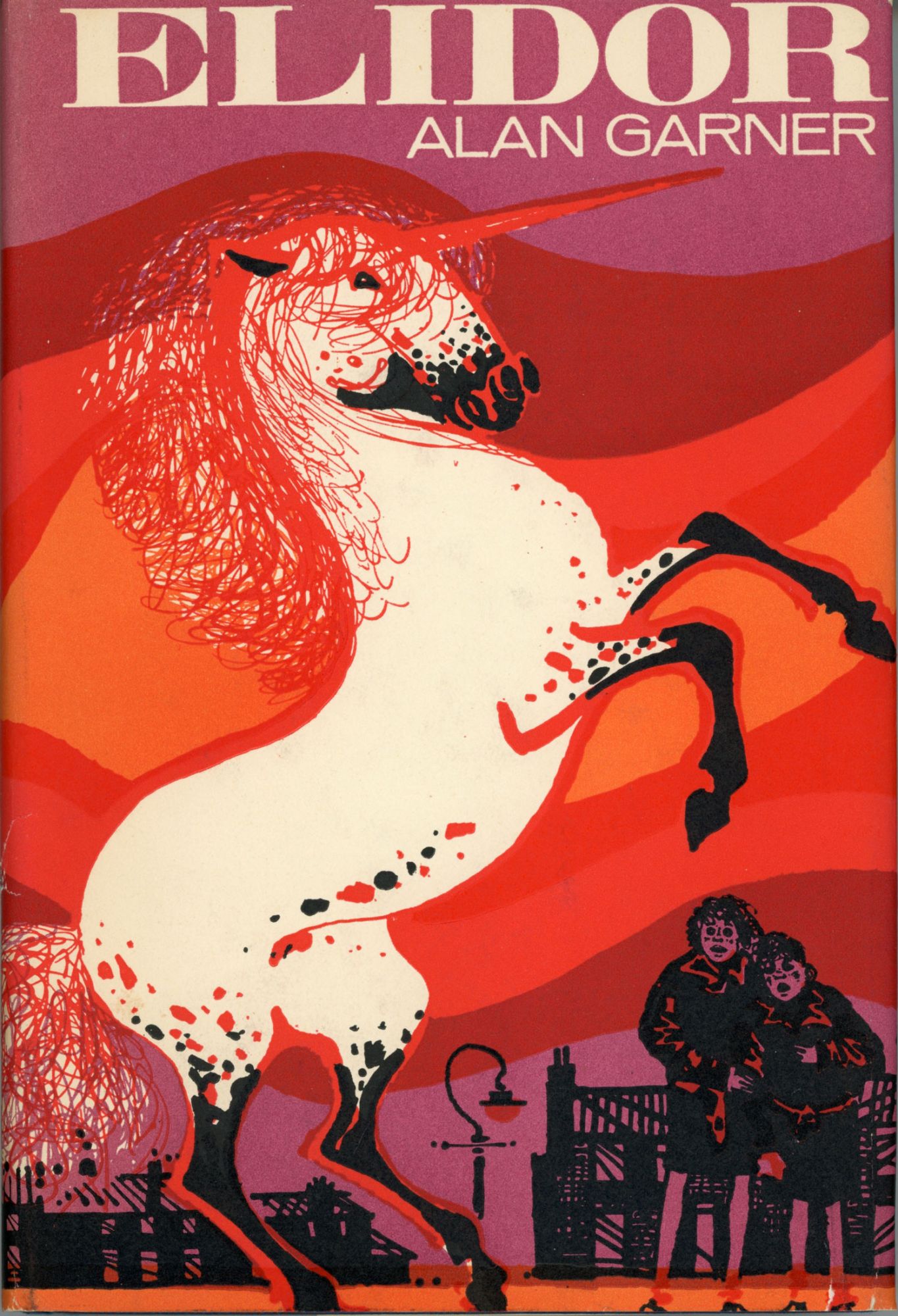

Wherever it comes from, perhaps a treacle well of ideas that heals the idea-less writer, it served Garner well over the years. Weirdstone and its sequel Gomrath were followed, over the next decade, by Elidor,The Owl Service and Red Shift.

Elidor was the first book of Garner’s I encountered. I can’t remember which forward-thinking teacher at Britannia Bridge Primary School in Wigan decided to read it to us as a class sometime in the late 1970s, but I thank them profusely for it now. I had begun to explore fantasy and science fiction at that age, and I think I had started, if not finished, CS Lewis’s Narnia books, devoured from the mobile library that used to visit our street every Thursday evening. On the face of it, Elidor seemed cut from the same cloth: a group of children find a way into another world and are engaged in the ages-old battle of good versus evil.

But Elidor was actually cut from a far darker cloth, black and voluminous as the night. For a start, the book was set in urban Manchester, with a group of working class characters who are drawn to the other world through a derelict church. I was used to the jolly capers of Narnia, where the children had thrilling adventures then returned to their normal lives. The Pevensies seemed as fantastical as fauns to me, yet here in Elidor were kids like me. The other big difference was that the journey into Elidor was not without consequences; they didn’t leave the magic behind and get home in time for tea.

“No,” said Garner. “The magic comes and gets you.” Between writing Weirdstone and Gomrath, Garner had started working as a freelance television journalist for Granada and the North West BBC network. He fully admits that his first two books were not natural in terms of speech and characterisation of his young protagonists. His time working in television changed that.

“When I was first published people came to the strange conclusion that because I could write I could be happy in front of a camera,” said Garner. “It turned out to be true, but the reasoning was a bit barmy. What it taught me above all, and you can see this if you compare the first two books with Elidor, is that it showed me how to listen to people’s speech.

“Another thing that developed my ear was that I was working with Harold Riley, a Salford painter and he is as tuned in to Salford as I am to Alderley Edge. He took me round and showed me the mean streets, which for him were rich, cultural havens, and so that was what tuned me in to the area.”

I mention the Narnia books to Garner and he says with a laugh, “I disliked them intensely. It was only when I finished Elidor – which I wrote for its own sake, because if you write aggressively or polemically or snidely, then forget it – that I realised that the unconscious, or subconscious side of me had somehow written the anti-Narnia book.”

In the mid-1970s, Garner published four novellas which were collected together as The Stone Book Quartet and were a departure from his folkloric fantasies, each one telling the story of a child from a different generation of his family.

In the 1990s he returned with Strandloper, an adult tale of a man from Cheshire transported to Australia at the beginning of the 19th century and becoming enmeshed in the aboriginal earth magic of the Antipodes. Thursbitch, set in both the 18th century and the modern era, followed in 2003. And then, in 2012, he returned to the Alderley Edge of Weirdstone of Brisingamen.

“By the time Strandloper came out in 1996,” Garner told me, “I was meeting people who were successful writers, publishers, editors, and they all somewhere in the conversation would say to me ‘when’s the third book coming out?’ And I’d never said to anyone there was going to be a third book after Weirdstone and Gomrath, but over the years the intellectual side of me, the ignorant side of me, started asking what happens to kids who’ve gone through that experience, and have to be adults. What happens if you went through all that, or at least believed you’d been through it? And that was the start of Boneland.”

Half a century is a long time to wait to finish a trilogy. Garner sighs and thinks about it a bit longer. “I did originally see Weirdstone and Gomrath as a trilogy because I had so much material but to be honest, by the time I’d got to the end of the second book I was up to my gills with loathing for Colin and Susan.” He laughs for a long time. “Basically I made the mistake of using the children as lenses for the reader to view the story and that basically made them wimps.”

At one point, Garner even went as far as to write an alternative ending for The Moon of Gomrath that would have killed any idea of a third book stone dead. He pauses for but a moment then recites, “‘Yaroo,’ said Albanac. ‘I’ve been got at’. And he dropped dead. ‘We wins,’ said The Morrigan and she went upstairs to the room where Colin was and wrung the little bugger’s neck. The end.’” Garner collapses into peals of laughter.

But Boneland did come out about Colin, an adult astrophysicist, somewhat disturbed by his childhood adventures but with his neck resolutely unwrung. And that was Garner’s last novel, up to now. Wasn’t nine years a long time for a novel to percolate?

“Not for me,” laughs Garner. “I’ve been writing for 65 years and I’ve got 10 novels, so this is about right.”

I begin to enthuse about Treacle Walker, which I have finished just half an hour before I speak to Garner, so I’m still processing it. Young Joe, applying the ointment to his lazy eye, gets the ability to see both the “real” world and the world that lies behind it, the world in which Treacle Walker also dwells. I start to wonder if Garner is telling us that we all have the ability to see the world more than one way, but we often don’t.

“Watch the screen!” he commands me and I lift my head from my scribbling of shorthand notes. “I’m not preaching, I’m just telling a story. If you want to read that into the story, then good, excellent. The only area where I’m didactic… I’m going to be didactic, are you ready?” Garner points his finger sideways across the screen. “I’ve no time for writers who point the finger.” Then he shows me the palm of his hand. “What’s in my hand? Anything? Nothing? Okay, we’re done. Go and read something else now!”

What he means, of course, is that Alan Garner doesn’t tell you what his story is about. He shows you his story, and what you take away from it is up to you. “If a book is good,” he adds, “there are as many valid interpretations of it as there are readers. If a book is worth reading, it’s open to interpretation. This,” he opens his hand again, “not this,” he points his finger.

Garner has no problem with the time it takes him to write a book. It’s all about connections for him, joining the dots. Coming up with the different aspects that all come together in some strange confluence of elements in his writer’s mind to coalesce into that elusive, will o’the wisp of an idea that his particle physicist friend was so keen to be able to nail down.

It started with Bob Cywinski’s tale of Treacle Walker, and then an old folk tale that Garner remembered about a woman who is taken inside a hill by an ordinary man to deliver his wife’s baby; she is given an ointment to rub on the infant’s eyes and unwittingly gets some on her own, seeing the man for what he is, a prince of faerie, in regal raiment. When she sees him at market some time later he realises she has partaken of the cream and stabs out her eye which affords her the second sight.

Garner admits he doesn’t have many writer friends, he has surrounded himself with folklorists and archaeologists. But he’s also sometimes incongruously excited about technology. He tells me enthusiastically about his son at Stanford University putting him onto Metacrawler. “It’s a search engine that searches the search engines!” He put Treacle Walker into it and came up with a single link to a handwritten document.

“It was a scrap of paper from the 19th century from a land claim made by the Cherokee nation to get some of their land back,” he said. “The claimants had to be listed under their Cherokee names and their imposed translations into English. And there was Treacle Walker, who was a healer. That was the English translation of his name.”

Garner sits back, his eyes twinkling. “I couldn’t get any further with that, but what it does show, with my folkloric and historian’s hat on, is that Treacle Walker is something that is very old indeed, otherwise how could a barely-literate if literate at all tramp on the moors above Huddersfield in the early 20th century get the name of Treacle Walker? It’s still a mystery. But it’s a good ‘un.”

For Garner and wife Griselda, the past 18 months have not made a huge change to their lives in splendid isolation at home. “Selfishly, to my occasional shame, it was just business as usual, but better in a way. We’re half a mile from our nearest neighbour and if I look out of my window I can see for a miles and all I can see is trees and fields and they don’t change.” He shrugs. “That said, I have friends in London for whom lockdown was quite a different matter, and we also don’t live with three kids in a tower block.”

It’s a delicate question to ask, but given he has just turned 87 and his long gestation period between novels… but, does he have another book in him? Is he writing anything? Has he had one of those elusive ideas unexplainable even by a particle physicist?

He sits back, illuminated by a shaft of Cheshire sunlight lancing in through his window. “All I’ll say is… I’ve got that queasy feeling in the mornings. So I probably am, but even if I knew, I wouldn’t say anything. I’m not superstitious, I’m an arrogant Classicist. But at the same time you don’t speak about the fairies’ gold lest it turns to leaves in your pocket…”

Treacle Walker by Alan Garner is out now from 4th Estate

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks