How the ancient ‘Queen of the North’ was forgotten

She was a warrior like Boudicca and yet few today know who Cartimandua was. Is it time to put up statues of her, asks David Barnett

Andy Burnham, the mayor of Greater Manchester, has earned himself the nickname the King of the North for his campaigning ways. But Burnham is merely following in the footsteps of the region’s first actual ruler 2,000 years ago.

We all know of Boudicca, the warrior-queen of the Iceni tribe who took on the invading Romans in the 1st century AD. But Boudicca was never officially recognised as a queen, while her contemporary – who you’ve probably never heard of – was: Cartimandua.

I first heard of her a couple of months ago, when I was chairing a panel on northern writers at the Bradford Literary Festival. Two of the panellists both mentioned Cartimandua in their books – Kate Fox in Where There’s Bras, which tells lost stories of the women of the north, and Brian Groom’s Northerners: A History.

Both cited Nicki Howarth-Pollard’s 2008 book Cartimandua: Queen of the Brigantes, as the only real modern source of information. So Howarth-Pollard is the obvious first stop to discuss this forgotten queen.

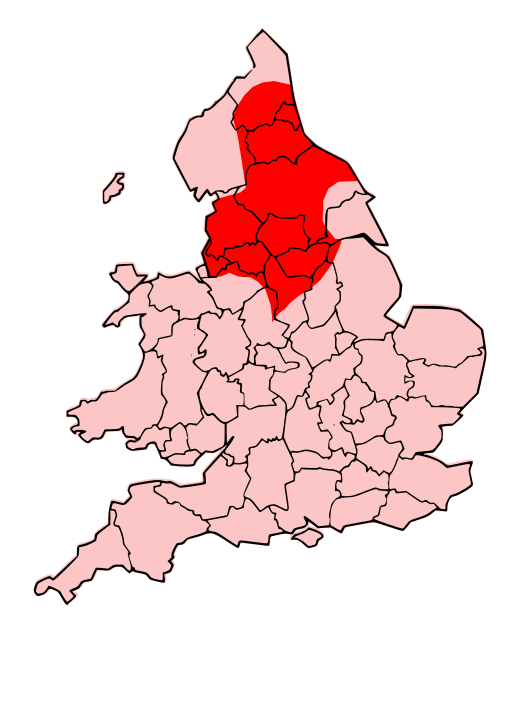

The potted history of Cartimandua is that she was the queen of the Brigantes, a Celtic people that lived in a huge area of Northern England, centred on Yorkshire. She came to power around 43AD, the time of Roman Emperor Claudius’s conquest of Britain, and ruled over what was at the time the biggest tribe in the isles.

Perhaps one of the reasons we know little about Cartimandua today is that unlike Boudicca, and the romanticised stories of her declarations of war against the occupying Romans, Cartimandua was much more of a stateswoman, working with rather than against the Romans in order to maintain peace.

In other words, Cartimandua might have just been dismissed as a collaborator, rather than as the vengeful warrior-queen that earned Boudicca her own statue in London. But is this fair?

According to Howarth-Pollard: “Context is everything. At the time of the conquest of Britain in AD 43, we were not yet a united kingdom but an area of distinct tribal domains.

“Brigantia was a vast expanse of territory stretching, it is argued, from Birrens, near the Scottish border, down to Little Chester, near Derby and covering most of the lands east to west in between.

“The Brigantes were thought to be a federation of smaller tribal units banded together under a single leader and that leader was female. Cartimandua was no puppet queen and Imperial forces never occupied her lands while she was in power.

“Instead, she had a reciprocal agreement with Rome – she was pivotal to their plans for Britain and due to her shrewd dealings with the Empire, she managed to utilise Roman support when she needed it, without losing independence for herself or her people.

“The south and east either surrendered or were defeated and so as the Romans moved north and west, Cartimandua’s support ensured that they were not attacked from the rear.”

One of the main problems that Howarth-Pollard faced when researching Cartimandua was the lack of historical documents. “I spoke to academics, archaeologists and experts in multiple fields to try and establish the details of her world. The main thing is that there were no ancient tribal texts so everything we do know about her was written by Roman authors and aimed at a Romanised audience. Most modern authors have just repeated these sources verbatim without bothering to question the motives behind writing them.”

Indeed, Cartimandua’s adeptness at managing the Romans might have disgruntled the invaders a little, she says, and even caused a bit of what we’d think of today as a smear campaign.

“Rich and influential Romans would not have wanted to hear about the political adeptness and tactical skills of the Brigantian queen,” says Howarth-Pollard. “So like the modern-day celebrity-hungry media, the Roman authors obligingly turned to the scandalous. Accusations of adultery and betrayal taint her memory and unfortunately, even today you will still read about the ‘power-hungry seductress’ and the ‘betrayer of freedom fighters’.”

That betrayal centred on Caratacus, leader of the Catuvellauni tribe, who had been harrying the Romans in Wales. After his guerrilla fighters were defeated in one battle he and his family sought sanctuary with the Brigantes. Cartimandua promptly handed him over to the Romans.

She further angered the Celts by divorcing her husband Venutius, throwing him over in favour of his own shield-bearer, Vellocatus.

All this sex and betrayal makes this a pretty juicy story worthy of any Game of Thrones episode, so it’s perhaps even more surprising Cartimandua’s history is so little-known.

“Her story should be more widely known as it gives a different slant on the whole story of the Roman invasion – not everyone fled, surrendered or was defeated,” says Howarth-Pollard. “She was the first hereditary tribal queen that we know about [Boudicca was not a queen in her own right but a wife to Prasutagus] and Cartimandua succeeded in protecting her people from the might of Rome.”

With the tide turning against Cartimandua, who narrowly avoided being captured by rebel factions goaded on by her ex-husband, she fled to Cheste (then Deva) and abandoned the Brigantia region to Venutius in 69AD, who didn’t last long running his former wife’s territory, and was soon defeated by the Romans. What happened to Cartimandua after that is lost in the mists of time.

For comedian and author Kate Fox, the whole story is absolutely fascinating because of “the fact that she was a Northern Queen, as powerful – or more powerful – than Boudicca, but has been erased. Her forgetting tells us more than her history – about the persistent downgrading of northern identities and icons.”

And the Cartimandua story has relevance to our lives today, says Fox. She says, “The north has not been ‘colonised’ by the south and yet there is a ‘coloniality’ of voice and culture which I think we are in denial about – and Cartimandua’s absence from history symbolises this for me.

“I also think she broadens the range of what’s allowed or valued in terms of myths and symbols of northern womanhood. We’re allowed matriarchs like Hilda Ogden, or Betty Boothroyd, but not leaders who displayed a full range of power, sexuality and defiance.

“The fact that her tribe would have identified her with the Celtic Goddess Brigid, who was a smith, a prophet, a poet and a warrior, tells us something about the breadth of complexity she had as an archetypal [as well as historic] figure.”

For Brian Groom, Cartimandua’s erasure is nothing short of scandalous. He says, “I wasn’t aware of Cartimandua until I started researching ‘northerners’. Even when I talk to history societies, hardly anyone has heard of her. She isn’t mentioned at all in the only previous general history of northern England [Frank Musgrove’s The North of England, 1990]. Even when she is mentioned in history books, she tends to get confined to a few disparaging lines compared with Boudicca.

“What little we know comes mainly from the Roman historian Tacitus, who portrays her – despite her collaboration with the Romans – as an adulterous betrayer of British men, even though there was at that time no British nation to betray – she divorced her husband, married his shield-bearer and was overthrown by a revolt. The only substantive modern source is Nicki Howarth’s very helpful book on her.

“She is the first British queen known to history and the first northerner we can identify [Tacitus consistently names her as a queen, but does not describe Boudicca as such]. For most of our history women have been denied public roles, so it’s remarkable that the first known northerner was a powerful woman. Faced with a brutal and powerful invader, she succeeded in keeping her territory free from annexation for up to 30 years, though ultimately the tensions this created overcame her.”

So history has effectively cancelled Cartimandua – isn’t it problematic that she did work with the Romans rather than took up weapons against them?

“Well resistance which is subtle resistance is often less recognised,” says Fox. “Cartimandua’s people lived and prospered for years. She made a strategic decision and must have constantly been strategising and skilfully negotiating in order to maintain a mix of autonomy for the Brigantes and cooperation with the Romans. But of course. that’s less of a ‘heroic’ narrative than a military rout.

“Views of Boudicca have shifted depending on how defiant female leaders from Elizabeth I onwards have been seen, whereas views on Cartimandua have mainly just been limited to the small amount that the biased Roman historian Tacitus wrote about her.”

Groom adds: “A key reason why Cartimandua is less well known than Boudicca is that Boudicca became portrayed as a resistance heroine, which appears more dramatic and patriotic – at least on a superficial level.

“Yet Boudicca’s revolt brought down a terrible retribution on her people, which Cartimandua largely avoided. Perceptions of both suffer from how women were viewed by the Romans. No Roman woman became an emperor. Female rulers on the empire’s fringes were seen as exotic, but their authority don’t square with Rome’s culture, so they invited disapproval. They were portrayed either as women of loose morals or as fierce and unladylike.”

So it seems it’s time for a reassessment of Cartimandua, Queen of the North, ruler of the Brigantes. Statues, perhaps? Lessons at school?

Groom says, “I would certainly like to see much greater awareness. If there is any northerner who deserves a statue, it is surely Cartimandua.

“It would be good to see her included on the school curriculum, though I’m not holding my breath. Most of all, I would like to see her acknowledged and taken seriously in history books. Given the increased emphasis today on women’s underappreciated role in history, there is so much we can learn from the story of the first known northerner.”

Fox agrees. “Of course I think she should be on school curricula, street names, pub signs, as a statue, with an education centre at Stanwick [her likely seat of rulership] and generally re-remembered. We have so few northern female role models as it is. But we seem reluctant to celebrate the ones we do have. For example, Hilda of Whitby was a great leader, administrator, educator and inspirer-but the gift shop at Whitby Abbey has just one postcard you can buy linked to her, but endless Dracula bats and coffins! We’ve only just got statues of Barbara Castle and Emmeline Pankhurst.

“The reclamation of northern feminist history has been gathering pace since the centenary of female suffrage in 2018, but recognising Cartimandua would give it much deeper historic and mythic grounding.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks