‘I was always scared to death of him, to be honest’: In search of the real St Francis of Assisi

William Cook explores the sites and artworks that inspired the National Gallery’s upcoming show about the enigmatic founder of the Franciscan order

Outside an ancient church in Rivotorto, a village in rural Umbria, the director of London’s National Gallery Gabriele Finaldi is telling a group of journalists (including your own agnostic correspondent) about St Francis of Assisi – one of the holiest men who ever lived. “This is the very origin of the community of Franciscans,” he tells us, as we step inside.

Who was St Francis? And what does he signify today? His meaning has shifted through the centuries, appropriated by every creed. For the liberation theologists of South America, he’s a champion of the downtrodden. For Mussolini, he was a nationalistic icon, “the most saintly of Italians, the most Italian of saints”. For lukewarm Anglicans like me, he’s more like a cross between Friar Tuck and Doctor Dolittle: a nice man who’s kind to animals, a friendly figure from a nursery tale. So why is Finaldi so keen on him? And why has he brought us here?

Finaldi is the curator of the National Gallery’s forthcoming exhibition about St Francis, and he’s here to show us the sites and artworks which prompted this groundbreaking show. As he explains, St Francis wasn’t only a key figure in medieval Christendom; he also had a profound effect on the development of Western art. Finaldi’s show straddles both sides of this story: the man who founded one of the world’s most important monastic orders, and the man who inspired many of the greatest artists of the last 800 years.

Our pilgrimage begins inside this church in Rivotorto, within the “sacred hovel” where St Francis and his followers found shelter. St Francis gave away everything he owned and lived a life of severe simplicity. This humble building still evokes that spirit of self-sacrifice. “Rivotorto is always perceived as the really joyful moment in the history of the order,” says Finaldi. “As the story of Francis progresses it becomes much more complicated. It becomes darker, and the great struggles in the Franciscan order begin.”

From Rivotorto, we drive on to the Basilica di Santa Maria degli Angeli, just outside the medieval walls of Assisi. This gigantic baroque church was built over another humble building, the Porziuncola – the tiny chapel where St Francis died. For 800 years it’s been a place of pilgrimage. Like the “sacred hovel” it has a potent aura. There are many pilgrims here today.

“I came here first as a tourist, in 1996,” says Father Eunan, the Franciscan monk from Belfast who guides us around the basilica. “I came back as a pilgrim, in 1998, and then I came back in 2003 to ask to join, and the friars are a little crazy here – they let me!” He calls the Porziuncola a dangerous place – a place with the power to transform your life.

St Francis was a fiery radical, a world away from the jolly image in children’s books

Visiting these sites gives you a vivid sense of the life and vocation of St Francis, but the other side of the story is the spectacular art he bequeathed. Within a century of his death in 1226, there were thousands of artworks devoted to him in churches all over Europe. The seedbed of that harvest is the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi – the highlight of our trip.

The Basilica of San Francesco is a striking combination of Romanesque and Gothic architecture. However, it’s not the exterior that draws the crowds but the pictures on the walls within. This building is a double-decker structure – two churches, built one above the other. Both are festooned with frescoes – scenes from the life of St Francis, painted by the greatest artists of the age. It’s like a kind of comic strip – a godsend for medieval worshippers, most of whom couldn’t read. Father Daniel, a Franciscan monk from Baltimore who shows us around, calls it “a bible of the poor”.

Moving between the Lower Church, with its earlier paintings from the early 13th century, and the Upper Church, adorned with later paintings from the late 13th century, you see how perceptions of St Francis changed. The earlier paintings focus on his supposed miracles. The later paintings focus on the biographical landmarks of his life.

As you ascend from the Lower Church, with its Romanesque architecture, to the Upper Church, with its Gothic architecture, this change of subject matter is reflected in a dramatic change of style. The earliest depictions of St Francis seem flat and lifeless. The later depictions are in three dimensions, portraying real people in real places. They herald the advent of the Renaissance, the dawning of a new era, when artists started to depict the world they saw around them. Assisi became a crucible for the new art of central Italy, which then spread in all directions, carried across the continent by Franciscan friars.

Would this revolution have happened anyway? Probably, eventually; but St Francis was undoubtedly a catalyst. “His example was so powerful, and so overwhelming,” explains Finaldi. There was something extraordinary about his personality, something exceptional about his biography, that dragged medieval art out of its conformist torpor – away from the rigid iconography of the dark ages and out into the light of day.

What was it about this man that galvanised great artists like Giotto and Cimabue? To answer this question, you need to realise that the real St Francis was a fiery radical, a world away from the jolly image in children’s books. “I was always scared to death of him, to be honest, because he was so intense, so committed,” Father Daniel tells me. “But he also had great humility.”

It was the life he lived that made him special. “Most saints rely on martyrdom or miracles,” says Joost Joustra, the co-curator of the National Gallery show, who joins us on this trip. “Francis really stands out.” This was a man so pure and selfless that he was called Alter Christus (Another Christ).

St Francis was born in Assisi around 1181, the only son of Pietro di Bernardone, a textile merchant. At first he looked set to follow his father into the family business. But he aspired to become a knight, and in 1202, when Assisi went to war with Perugia, he went away to fight. Captured at the Battle of Collestrada, he was a prisoner of war for the next year or so, which did lasting damage to his health.

He develops a certain kind of social thinking, about the responsibility society has towards the poor

In 1205, after a pilgrimage to Rome, he renounced his wealthy background and his former life of pleasure, instead adopting an austere religious life. His affluent father was aghast. The two men had a public showdown outside the Santa Maria church here in Assisi, whereupon Francis took off all his clothes, placed them at his father’s feet and told him: “You are no longer my father.”

Francis was merely following the teachings of Jesus Christ; but then, as now, this was a lifestyle few Christians dared adopt in its entirety. In Assisi, as elsewhere, the church had become a bastion of the establishment. Its monasteries were wealthy, and its clerics enjoyed a comfortable life. Francis dared to take the Gospel literally – nursing lepers, begging for alms, comforting the dispossessed. As Finaldi says: “He develops a certain kind of social thinking, about the responsibility society has towards the poor.”

Despite the severity of his lifestyle, Francis attracted lots of acolytes. “He didn’t really set out to found an order, but the Lord gave him brothers,” explains Father Daniel. Any new monastic order required the blessing of the Pope, so in 1209 Francis went to Rome to seek an audience with Pope Innocent III. Bolstered by his endorsement, this nascent order went from strength to strength.

Why did the Pope give the Franciscans his blessing? Because Francis had incredible charisma, but also because he posed no schismatic threat. As Joost Joustra says: “Francis is a surprisingly non-theological saint.” His Christianity was practical and unintellectual – there was nothing heretical about it. He simply wanted to put the Sermon on the Mount into practice, “to live the Holy Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ in chastity, obedience, and without anything of our own”, as he put it (I once asked a Franciscan monk which was the hardest vow: poverty, obedience or chastity? Obedience by far, he said).

Throughout his ministry, Francis retained the common touch. He was never ordained, remaining a mere deacon. He cared for animals as much as people, he ministered to children as well as adults. In our time of climate crisis, his love of nature seems prophetic. On Christmas Eve 1223, he re-enacted the Nativity, complete with ox and ass and manger – thus initiating the Advent traditions of Nativity plays and Christmas cribs.

Within his lifetime, the Franciscan order spread rapidly across Europe, yet his brotherhood soon became a victim of its own success. Francis had forsaken all possessions, but as his order flourished donations flooded in. What had begun as a ragbag revolt quickly became an institution. Sidelined by his more mainstream brethren, who weren’t quite so keen on roughing it, he retreated to the hilltop refuge of La Verna to fast and pray. “Francis was a tough act to follow,” says Father Daniel. “He’s a tough act to follow today.”

I don’t think you can do an exhibition on the art of Francis without considering spiritual aspects. Francis as a teacher, Francis as an inspirational person for our time

We set off the next morning, bright and early, to La Verna. Father Francesco, one of the monks who lives up there, shows us around. “It’s not a museum,” he tells us. “It’s a living place.” You can see why Francis sought sanctuary here. You get a great view from the summit, over a vast arena of hills and valleys. If you believe in God (as I try, and often fail, to do) you’ll feel a lot closer to him up here.

Mind you, I must confess this is the place where I part company with the St Francis of the Catholic faith. According to his hagiographers, La Verna is where he became the first believer to receive the stigmata – the physical manifestation of the crucifixion wounds of Jesus Christ.

Whether you regard this as fact or fiction (or maybe even self-mutilation?), for me it diminishes the simple strength of the Franciscan story. Unlike Doubting Thomas, I don’t need physical proof to believe in him, or the man he strove to emulate. I don’t need miracles or relics to convince me he was a true follower of Christ.

However, I guess my attitude has been shaped by my Anglican upbringing. Gently, persuasively, Father Francesco explains it from a Catholic perspective. “It’s what you feel when you find someone who really loves you – you feel their pain,” he says. “That’s the meaning of stigmata.” When he puts it like that, I understand his point of view.

In 1224, in poor health, Francis was taken back to Assisi, to the convent of San Damiano, where Chiara di Offreduccio, a follower of Francis, had established a female Franciscan order (aka the Poor Clares). It was here that Francis wrote his Canticle of the Sun, a celebration of the natural world which anticipates contemporary ecology. By the time he died, in 1226, in Porzuincola, there were thousands of Franciscans all over Europe.

Yet despite his universal appeal, most of the main incidents of his life take place in and around Assisi. If you want to follow in his footsteps, you won’t have far to go. “He’s born here, right beside the main piazza,” says Finaldi. “He starts rebuilding the church of San Damiano, which is just outside the walls here – literally a few hundred yards away. He then moves to Rivotorto, which is a mile down the road – the Porziuncola is another mile further on.”

The long aftermath of Francis’s life is just as interesting as his life story. He was canonised in 1228, only two years after he died. In 1229 Thomas of Celano wrote the first of many biographies, charting his transformation from “vain and arrogant” youth to Alter Christus. In 1288, barely a lifetime later, Nicholas IV became the first Franciscan Pope.

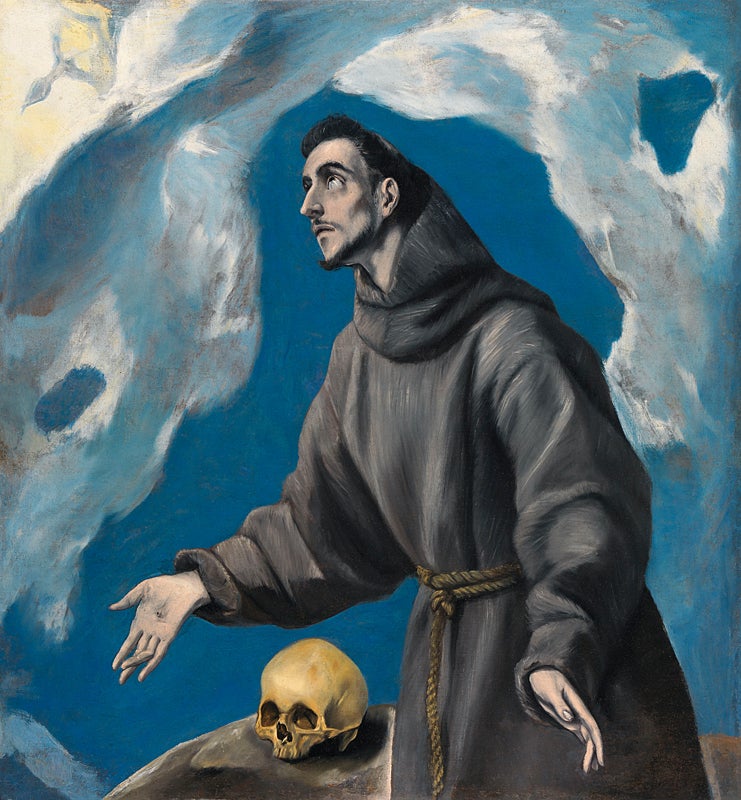

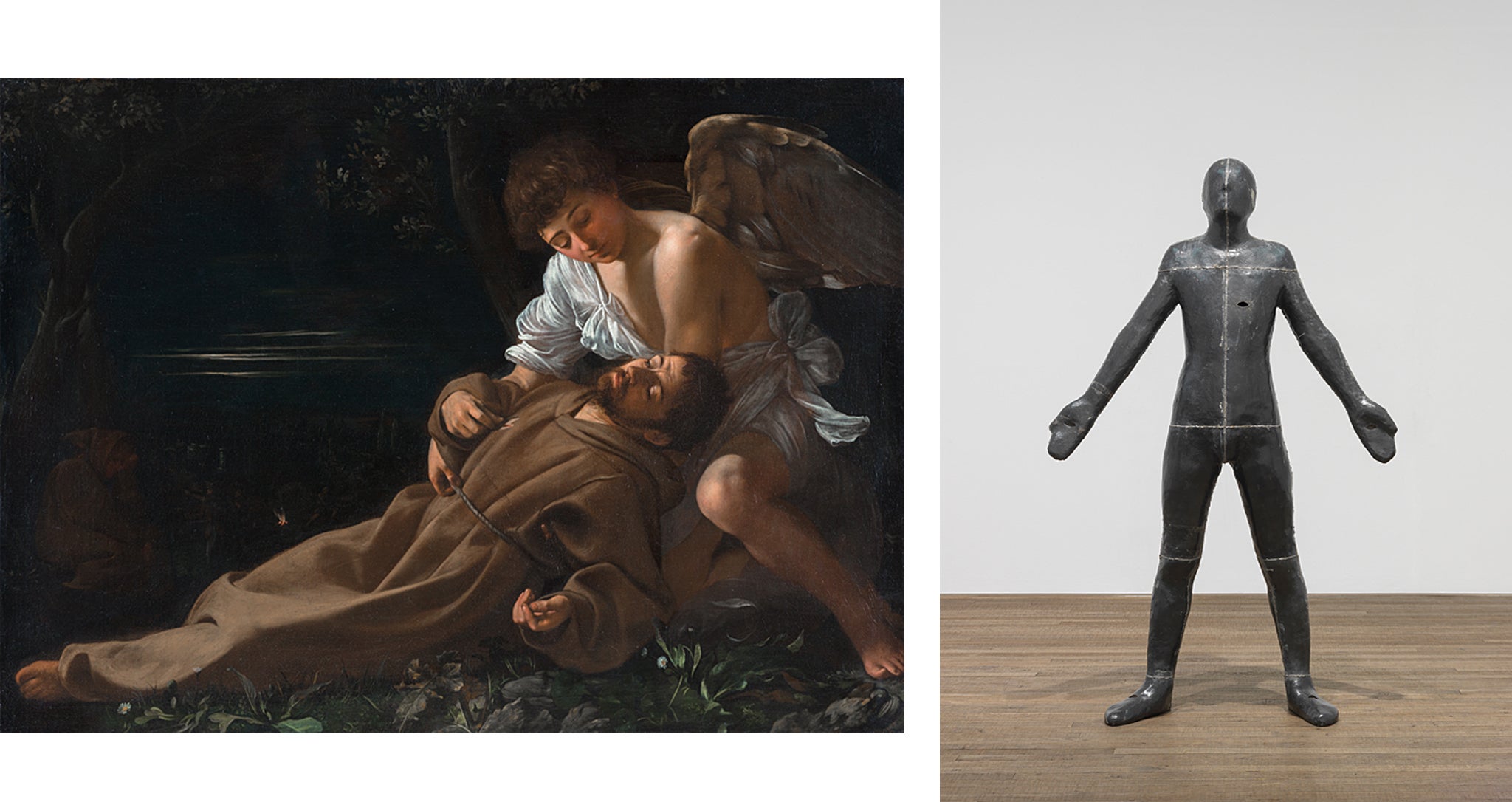

His role extends way beyond religion – he’s become a cultural figure, too. In the new National Gallery exhibition there are artworks from every century since his death, from Old Masters like Botticelli, El Greco and Caravaggio to works by living artists like Antony Gormley and Richard Long.

And although this show is primarily about the art, there will be a religious dimension too. “There will be relics there – things that actually have a holy, sacred significance,” says Joost Joustra. “I don’t think you can do an exhibition on the art of Francis without considering spiritual aspects,” concurs Finaldi. “Francis as a teacher, Francis as an inspirational person for our time.”

We conclude our pilgrimage at the Basilica of Santa Chiara, in Assisi, which houses the tomb of St Francis’s friend and follower St Clare. It was here that St Francis was first buried, in 1226, before his interment in the Basilica of San Francesco. The Basilica of Santa Chiara also contains the 12th-century crucifix of San Damiano, which spoke to him and inspired his holy mission. I sat in front of it for a while, and tried to pray, but it didn’t speak to me.

At Perugia airport, waiting for my Ryanair flight back to Stansted, I find an unfamiliar quote I’d scribbled down during our tour. At first, I assume it must be something Gabriele Finaldi said, but then I realise it’s from the first biography of St Francis, written by Thomas of Celano in 1229. “He felt this mysterious change within himself, but he could not describe it,” wrote Thomas. “So, it is better for us to remain silent about it too.”

Saint Francis of Assisi is at the National Gallery in London from 6 May until 30 July, admission free

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks