The legacy of Art Nouveau lives on in Brussels

William Cook examines the triumphant return of the style to its spiritual home in the Belgian capital

Down a quiet sidestreet in Brussels, just off Avenue Louise, stands a terraced house that transformed our idea of architecture and design. The Hotel Tassel isn’t a hotel – in French, the word merely means a grand house, and this house isn’t even all that grand. Yet 130 years since it was built, the Hotel Tassel still looks radical, for it was this building that sparked a revolution in the arts called Art Nouveau.

Art Nouveau is difficult to define, but you know it when you see it. It’s more than an architectural or aesthetic style – it’s an attitude, a state of mind. It mimics the contours of leaves and flowers, the swirl of flowing water. Its inspirations were naturalistic, yet its techniques and materials were modern. A century since its sudden demise, amid the industrial slaughter of the First World War, it remains defiantly avant-garde.

This is the year of Art Nouveau in Brussels. The city is celebrating its unique Art Nouveau heritage with a season of special events. Brussels was the birthplace of Art Nouveau, the most beautiful art form of modern times. So why did the Brusselaars try so hard to destroy it?

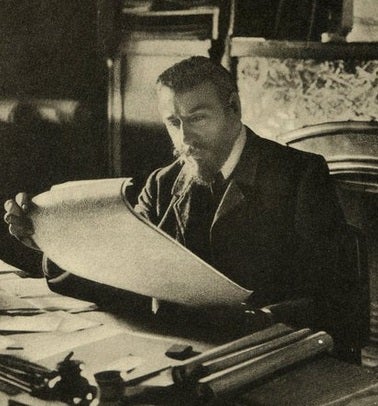

For 20 years or so, from the 1890s to the First World War, Art Nouveau galvanised every avenue of the visual and decorative arts. From painting to printing, from fashion to furnishing, no genre was immune. It swept through every western nation, mutating as it went, reshaped by Gustav Klimt in Vienna, Antoni Gaudi in Barcelona and Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow. Yet it started here in Brussels, with the man who built the Hotel Tassel, Belgian architect and designer Victor Horta.

Surreal and futuristic, Horta’s Hotel Tassel was a sensation, inspiring Belgian architects and designers like Paul Hankar and Henry van de Velde. Art Nouveau houses sprang up all over Brussels. It wasn’t only the exteriors of these buildings that were revolutionary; the interiors were equally spectacular, lavishly decorated with murals, stained glass and mosaics – all executed in the florid Art Nouveau style. Even the bathroom fittings and lavatories were beautiful. From furniture to tableware, each building was a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total, integrated work of art.

Why did Art Nouveau take off in Brussels? Partly because Belgium was a young country – founded in 1830, its stylistic instincts were forward-looking – but above all, because it had industrialised at an exponential rate. Profits flooded into Brussels, creating a new upper-middle class who’d made their own money rather than inheriting it.

To inhabit an Art Nouveau house was a mark of wealth and status. It showed you were successful – those big windows weren’t just designed to let in more light, they also showed off the riches within – but it also showed you were liberal and progressive, rather than a reactionary arriviste, trying to ape the landed gentry.

If it hadn’t been for the First World War, Art Nouveau might have become the defining style of the 20th Century. Instead, it became an aesthetic dead-end. The main reason was money. With its emphasis on beauty, Art Nouveau was expensive. After the “war to end all wars”, such extravagance was unaffordable. However, there was a deeper reason too. Art Nouveau reflected the optimism of the Belle Epoque, an era when anything seemed possible. After the carnage of the trenches, such exuberance was woefully passé.

During the Twenties and Thirties, Victor Horta followed the spirit of the times, shifting from flamboyant Art Nouveau to more streamlined Art Deco (Brussels’ Central Station and Bozar arts centre are two examples of his later style). Mercifully, Brussels came through the Second World War relatively unscathed, and when Horta died in 1947, its Art Nouveau cityscape was still largely intact. Yet tragically, in the Fifties and Sixties, many of these antique landmarks were torn down to make way for ugly tower blocks.

As always, the overriding motive for this wanton destruction was greed. Most Art Nouveau buildings were in private hands, with few planning restrictions to restrain their owners. Many were built on large plots, which could easily accommodate far bigger buildings. Brutalism was all the rage, Art Nouveau was out of fashion. To bulldoze an Art Nouveau mansion and replace it with high-rise flats or offices was an easy way to make a profit.

There was still a market for Art Nouveau decor, but ironically this demand merely fuelled the destructive process. The contents of these houses could be sold to museums or private collectors, providing an added incentive for demolition. Preserving Art Nouveau artefacts in museums was better than nothing, but it was no substitute for seeing them in the buildings they’d been designed for. Collections created for specific sites were broken up and dispersed. This iconoclastic fervour even spawned a new word: “Brusselisation”. The seedbed of Art Nouveau had become a synonym for architectural vandalism.

Brusselisation reached its peak in 1965, when Horta’s iconic Maison du Peuple was dismantled, and replaced by yet another anonymous skyscraper. Built for the Belgian Workers’ Party, the Maison du Peuple was one of Horta’s biggest buildings – but it wasn’t just its size that made it significant.

Built on an irregular, sloping site, it was a technical triumph, and its socialist function refuted the familiar accusation that Art Nouveau was merely an art form for the rich. Hundreds of architects protested in Belgium and beyond, to no avail.

The destruction of the Maison du Peuple was a wake-up call. It wasn’t the last Art Nouveau building in Brussels to be demolished, but from then on Brusselaars began to take the necessary steps to protect these treasures from developers. Today there are hundreds of Art Nouveau buildings scattered around Brussels, and though hundreds more have been lost, there’s still a richer Art Nouveau legacy here than in any other European city.

Most of these buildings are private homes, but for several weekends every year, many open their doors to visitors. Some are now museums, including the Old England department store – now a museum of musical instruments – and Horta’s Magasins Waucquez, a former furniture showroom that now houses the Belgian Comic Strip Centre (the clean lines of Herge, creator of Tintin, bear a significant resemblance to the sgraffito reliefs of Art Nouveau).

However, the finest relic is Horta’s home and workshop, which provides an intimate insight into his professional and domestic life. The first Art Nouveau building to receive protection from the Belgian state, it opened as a museum in 1969, a few years after the obliteration of the Maison du Peuple.

Adorned with intricate metalwork, and flooded with natural light, it’s a kaleidoscope of exquisite detail: but the most remarkable thing about it is the overall effect. There’s an incredible sense of peace, and it takes you a while to realise why. Finally, the penny drops: there are no straight lines, no sharp edges. It’s closer to the natural world than the geometric structures we inhabit.

That’s why Art Nouveau is so precious. That’s why so many people adore it, even folk with little interest in architecture or design (the Horta Museum, in a suburban backstreet, attracts 50,000 visitors a year). During the last hundred years, the buildings that we live in have become increasingly functional and impersonal. As soon as you step inside Horta’s house, you find yourself thinking, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to live in a place like this.”

“His goal was to put personality into architecture,” explains the curator of the Horta Museum, Benjamin Zurstrassen, over coffee in his cosy office above the museum. Yet Horta was also supremely practical. His Hotel Solvay was the first Belgian building to be lit by electricity. As in all the best buildings, form follows function; the kindergarten he built in 1895 is still a nursery school today.

Horta’s father was a shoemaker, who instilled in him an appreciation of fine craftsmanship. He rejected the elitist notion that the architect is a creative artiste and the builder or engineer a mere artisan. He broke down the snobbish, class barrier between fine art and applied arts.

There are various other Art Nouveau museums around town (Horta’s Maison Autrique is especially atmospheric) but the best way to get a sense of this eccentric style is to simply wander around. You can join a guided tour, but for me, the greatest pleasure is when I head out on my own, following a walking trail in an old guidebook, past rows of humdrum modern houses, until I come across an Art Nouveau townhouse – an oasis of delicate artistry amid the dull conformity of contemporary urban life.

“It’s so easy to get in touch with the heritage of Horta because it speaks to us,” says Zurstrassen. “It’s the play of light, it’s the opening of space, it’s the beauty of the colours, the beauty of the materials. All those things can speak to anyone.”

And now, after decades in the doldrums, Art Nouveau is back in fashion. I dropped into the Hotel Hannon, a gorgeous Art Nouveau villa designed by Jules Brunfaut, to admire the ongoing renovation. After several years of meticulous restoration, it will reopen as an Art Nouveau museum. Brussels’ Musee Art & Histoire is inaugurating a new Art Nouveau wing. Brafa, Brussels’ annual art fair, is focusing on Art Nouveau this year.

“Now, with this very special year, you see many new buildings which open in Brussels, which is fantastic news,” says Zurstrassen. Too many of those amazing buildings have been lost, but thankfully the future of these survivors seems secure. A hundred and thirty years since its inception, Art Nouveau has never been more topical. As our interest in ecology grows, amid mounting concern about the future of our planet, the connections that men like Horta made between nature and architecture seem uncannily prophetic.

Travelling around Europe, I’ve stumbled across Art Nouveau buildings in all sorts of unlikely places, and wherever I find them it lifts my spirits like no other architectural style. There are lots in Riga, the capital of Latvia. There’s quite a lot in Nancy, in France. There’s even some in Tournai, a sleepy Belgian town near the French border. “There are as many Arts Nouveaux as there are artists, and as many Arts Nouveaux as there are countries,” says Zurstrassen. But nowhere is there such a wide array as here in Brussels. And the fact that you have to hunt for them makes them even more special when you find them.

I finished my Art Nouveau odyssey at Brussels' Musee Art & Histoire. I’d come to meet Werner Adriaenssens, curator of the museum’s 20th-century collections (and the brains behind a superb Henry van de Velde retrospective here, back in 2014). When I arrive, he’s packing up some Horta cutlery. He takes time out to show me the museum’s unrivalled collection of Art Nouveau glass, ceramics and silverware.

So why is all this stuff worth saving, I ask him? After all, other styles come and go, and most of them are eventually forgotten. Most buildings, most objects, are eventually destroyed. “It’s important because it’s the beginning of a new world,” he tells me. He's quite right, of course. It was the harbinger of a new society, the first modern art form, the advent of popular culture.

“Art Nouveau is the first Belgian style,” says Adriaenssens, and as I leave the museum I come across a particularly stunning example. The Maison Cauchie was the house and studio of the artist, architect and designer Paul Cauchie, and the entire frontage is an advertisement for his decorative talents. “Par Nous, Pour Nous” (By Us, For Us) reads the sign outside. It feels like a fitting motto for Brussels’ year of Art Nouveau festivities. After the dark days of Brusselisation, Art Nouveau has finally come home.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments