A forgotten Italian Impressionist reemerges

Giuseppe De Nittis was enormously talented and highly skilled and yet remains relatively unknown, writes Philip Kennicott. The artist’s early death may have something to do with that

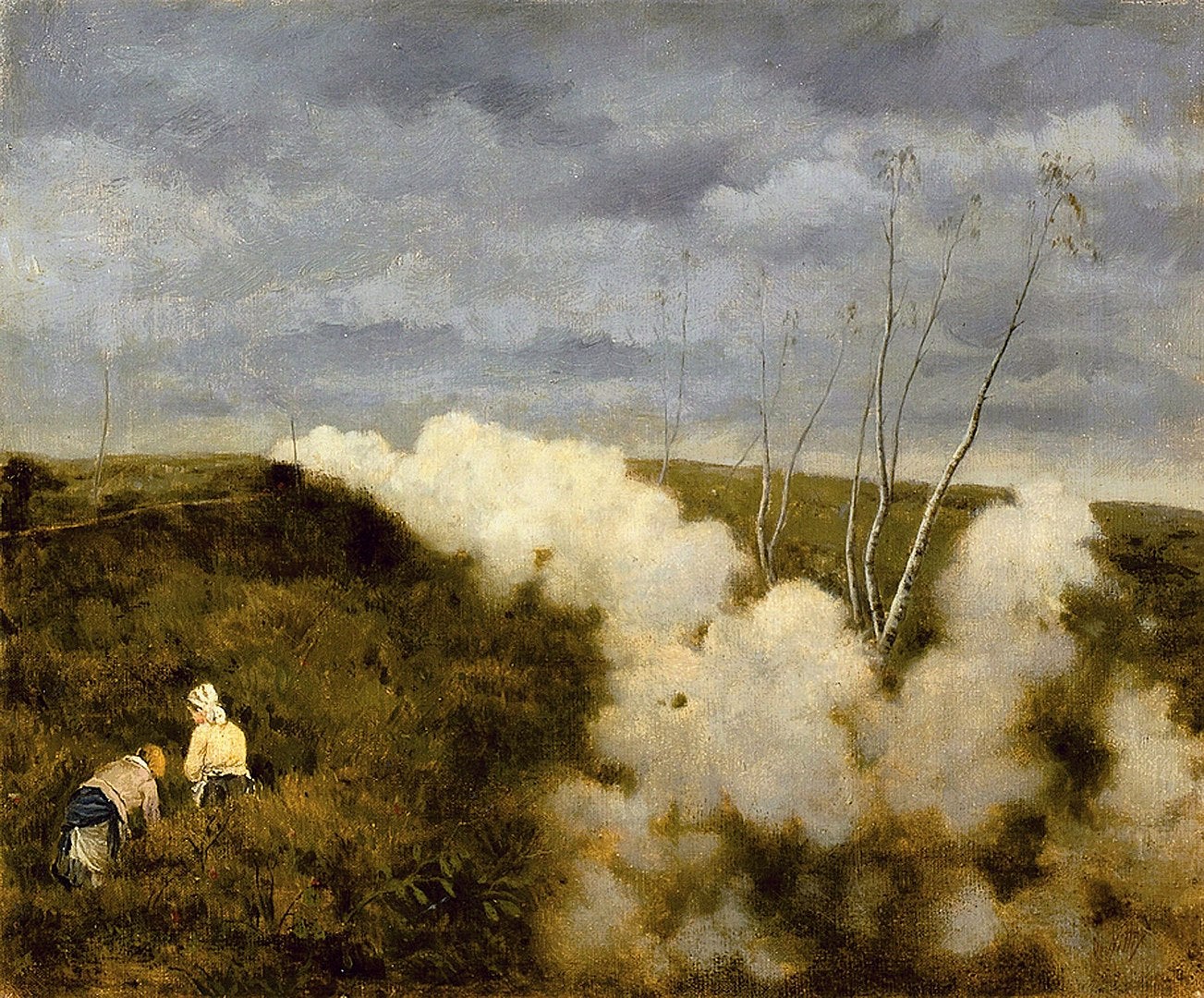

The train in Giuseppe De Nittis’s 1869 painting The Train Passes is there mostly by implication. A thick plume of white smoke or steam suggests the presence of an engine, and a small, dark form on the horizon seems to be its origin. But the bleak landscape of a few, spindly, leafless trees underscores the real subject: a world transformed by trains, coal and industry, and cities and countries brought into new intimacy by extensive networks of rail, roads and waterways.

De Nittis, whose work is surveyed in a new and engaging exhibition in the US called “Giuseppe De Nittis: An Italian Impressionist in Paris”, was born to a prosperous family in Apulia, in the south of Italy. But he also worked in Paris and London, was friends with Manet, Degas and Gustave Caillebotte, and exhibited in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874 in Paris. He had built a substantial career as a painter before his sudden death from a stroke at age 38 in 1884.

He was enormously talented and highly skilled, with a unique eye and sensibility, yet remains relatively unknown. De Nittis’s early death may have something to do with that. But more likely, his facility as a painter, and his ability to produce both polished salon work and ambitious visual experiments, have made him a difficult artist to define. As one of the catalogue essays for this exhibition observes, he was a “man in the middle.” And art history isn’t kind to anything that smacks of compromise or indecision.

Art museums are well stocked with lesser Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, artists who caught the drift but not the essence of the new painting styles that emerged in Paris in the second half of the 19th century. De Nittis was not that sort of artist. His exploration of colour and composition was as distinctive and even radical as any by his better-known friends and colleagues. But he was deeply and unapologetically bourgeois in his basic worldview, and elegant dresses, sumptuous fabrics and beautiful faces were as attractive to him as light refracted through clouds, mist or smog.

An exhibition of De Nittis’s work in Paris more than a decade ago used the subtitle “elegant modernity” to describe his work, and it is his relation to elegance that may have limited his posthumous reputation. When he painted nightlife, he didn’t turn to the demimonde of raucous cafes or circus spectacles, but to the soft and flattering light of a sumptuous salon. When he painted the women of Paris, they weren’t bleary-eyed from too much booze or yielding their bodies to the intrusive gaze of male clients and patrons. They were well-dressed, self-possessed and alert to the world around them.

In a late work, from 1884, De Nittis captured his wife and son having breakfast at an outdoor table in a well-manicured garden. The colours have the brightness and glare of Manet, and you may wish you had sunglasses when looking at the sun-drenched grass in the background. But despite that, the atmosphere is one of gentility and calm. The fine dishes and flowers on the table invite the viewer to linger in a pool of perfect shade. The artist will unsettle our sense of colour and light, but he won’t disturb breakfast.

There’s no seamy underside to these works, which are both elegant and modern, as if there is no contradiction between the two ideas. For De Nittis, there probably wasn’t. But that doesn’t make him a complacent or bland artist, especially if you view his salon elegance in the larger context of his early landscapes, including that painting of a train passing.

The elusive train and the blasted trees both suggest unseen forces. It isn’t even clear which way the train is going, given what feels like a surge of smoke wafting toward the viewer (carried by wind faster than the advancing train itself, or drifting toward us lazily as the train passes into the background?). Roads that seem to hurtle into the distance were a common theme of De Nittis’s early work, as if he were trying to capture both his ambition – to make art in the capital of the 19th century – and a growing sense of displacement, as transportation networks erased the distance between Naples and Paris, and effaced ideas of home and permanence.

His later cityscapes in Paris have a similar sense of unease. Paris was transformed during the years De Nittis lived there (he settled in Paris permanently in 1868). War and revolution left their scars, and the massive dislocation of Baron Haussmann’s urban renewal efforts made the city a perpetual building site, full of incipient order and beauty as well as the chaos and disruption of construction.

The grittiness of urban life is present in De Nittis’s work not through social markers like poverty or exploitation, but architecturally. The street scene captured in his 1875 The Place des Pyramides is as cold and damp as the glistening cobblestones of Caillebotte’s 1877 Paris Street; Rainy Day. But the scaffolding around the building, the jumble of street signage and the lowering clouds leave the impression that the elegant people scattered throughout the crowd aren’t completely at home in this evolving space, nor fully in control of it. You may feel your hand instinctively reach for the pocket that has your wallet, or for a tighter grip on your purse.

Unseen, even cataclysmic forces are present in a remarkable series of paintings De Nittis made of Mount Vesuvius in 1872. In two images, he captures not just the eruption of the volcano, but also the rush of spectators and day-trippers caught up in the drama. These works were too radical for De Nittis’s dealer at the time, but in the same year, he produced one of his first great successes, The Road From Naples to Brindisi, which seems superficially a more conventional painting until you start looking at it closely.

Heat radiates from the wide-open, treeless street, while a man’s leg sticks out of the door of a carriage, leaving us uncertain whether is jumping in or tumbling out. The surrounding landscape is flat and without any distinguishing features, and the sky has a lazy, torrid summer blankness. The people present, including the one attached to that enigmatic leg sticking out of the carriage, are trapped in some in-between space, going and coming without ever arriving or staying.

These are stronger, more interesting, more compelling paintings than some of the elegant Parisian scenes De Nittis would make a few years later. But there’s no sense that his ambiguous landscapes or uneasy city views are somehow more authentic to the artist’s true sensibility than his salon-friendly work, the ladies ice-skating or watching horse races or stirring a cup of tea in a fancy garden. They are not radically different, or incompatible views of the world, but rather, two views of the same world, highly interdependent on each other’s innate truth. Elegance has its cost. Modernity disrupted time and space, and made it a lot cheaper for ordinary people to set a fine table and dress up for the evening.

De Nittis died young, famous, respected, well-liked and deeply in debt. His personal ties to the Impressionists remained strong, though he kept his professional distance from the label of impressionism. The new exhibition, curated by Renato Miracco, leaves it uncertain which direction De Nittis might have gone, which tendency – to elegance, or modernity? – might have gained sway. Full disclosure: Miracco is a friend. But the exhibition he has assembled lets De Nittis speak for himself. And De Nittis speaks clearly, with a distinct and individual voice, and while it may seem that he was “a man in the middle,” the work argues otherwise. He painted the world just as he saw it, whether in the harsh glare of a southern sun or the warm glow of gaslight. Those worlds were connected, and he inhabited both.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments