Amsterdam’s new Van Gogh exhibition paints a portrait of familial affection

The story of how Theo, Jo and Vincent Willem preserved and promoted Van Gogh’s oeuvre is a tale of triumph over adversity, writes William Cook

Here in Amsterdam, the Van Gogh Museum is throwing a spectacular birthday party – not for Vincent van Gogh but for the museum itself. It’s 50 years since this gallery opened, back in 1973. The home of the world’s biggest Van Gogh collection, it attracts millions of visitors every year.

However, this golden jubilee isn’t just about the numbers. What makes the Van Gogh Museum so special is its unique connection with three members of Van Gogh’s family – his brother Theo, Theo’s wife, Jo, and their only child, Vincent Willem. It was this familial trio who kept Van Gogh’s legacy alive. Without them, this splendid museum would not exist, and Van Gogh never would have become the iconic figure who is so familiar to us today.

The story of how Theo, Jo and Vincent Willem preserved and promoted Van Gogh’s oeuvre is a tale of triumph over adversity – a reminder that even the greatest painters can never do it on their own. As Van Gogh said himself: “As an artist, one is merely a link in a chain.” This story is the subject of the Van Gogh Museum’s new exhibition, Choosing Vincent.

“We wanted to kick off our jubilee year with a big thank you to the Van Gogh family,” says the show’s curator, Lisa Smit, but this exhibition does more than that. It reveals that this trio were central to Van Gogh’s posthumous success. It shows how they transformed an unknown artist into a worldwide superstar.

Vincent van Gogh’s biography has become so familiar, it’s acquired a kind of mythic status: the tortured, tormented genius toiling alone in his lonely garret, dying unknown and unacknowledged. Like most legends, there’s a good deal of truth in it; but it also leaves a lot out.

Yes, Van Gogh had a difficult life that led him down the road to suicide. Yes, he’d only sold one painting when he died. Yet although he was often alone, shunned by polite society and neglected by the art world, he always had one man who believed in him: his younger brother Theo.

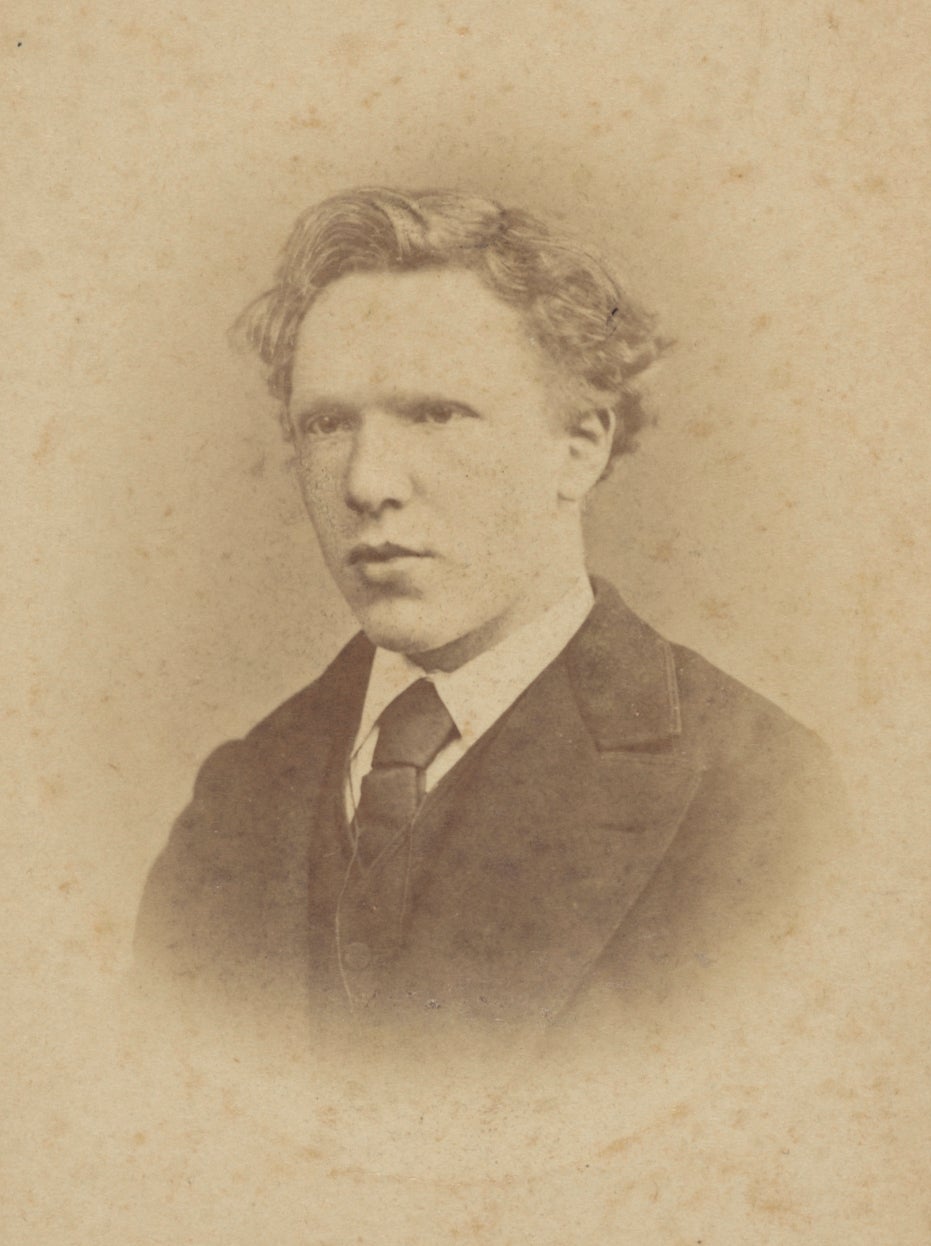

Born in 1853, in Zundert, a small town in the Netherlands, the son of a Protestant pastor, Vincent van Gogh was the eldest of six children. He had three younger sisters and two younger brothers. He got along well with all of them but it was his brother Theo who became his lifelong soulmate, “My best friend,” as Vincent put it. “More friends than brothers.”

Vincent’s uncle was a partner in the international art dealers Goupil & Cie. Thanks to him, Vincent and Theo were both apprenticed to this prestigious firm. Theo prospered there but Vincent floundered. Fired by Goupil & Cie, incapable of holding down a steady job, he drifted around for several years, scratching a living as an itinerant teacher and a lay preacher, until 1880 when, aged 27, he decided to become an artist.

Vincent had a passion for art but he’d only ever drawn a few rough sketches. He knew it’d be years before he could even hope to pay his way. He’d need to learn from scratch and he had no money to support himself. If it hadn’t been for Theo, this improbable ambition would have been stillborn.

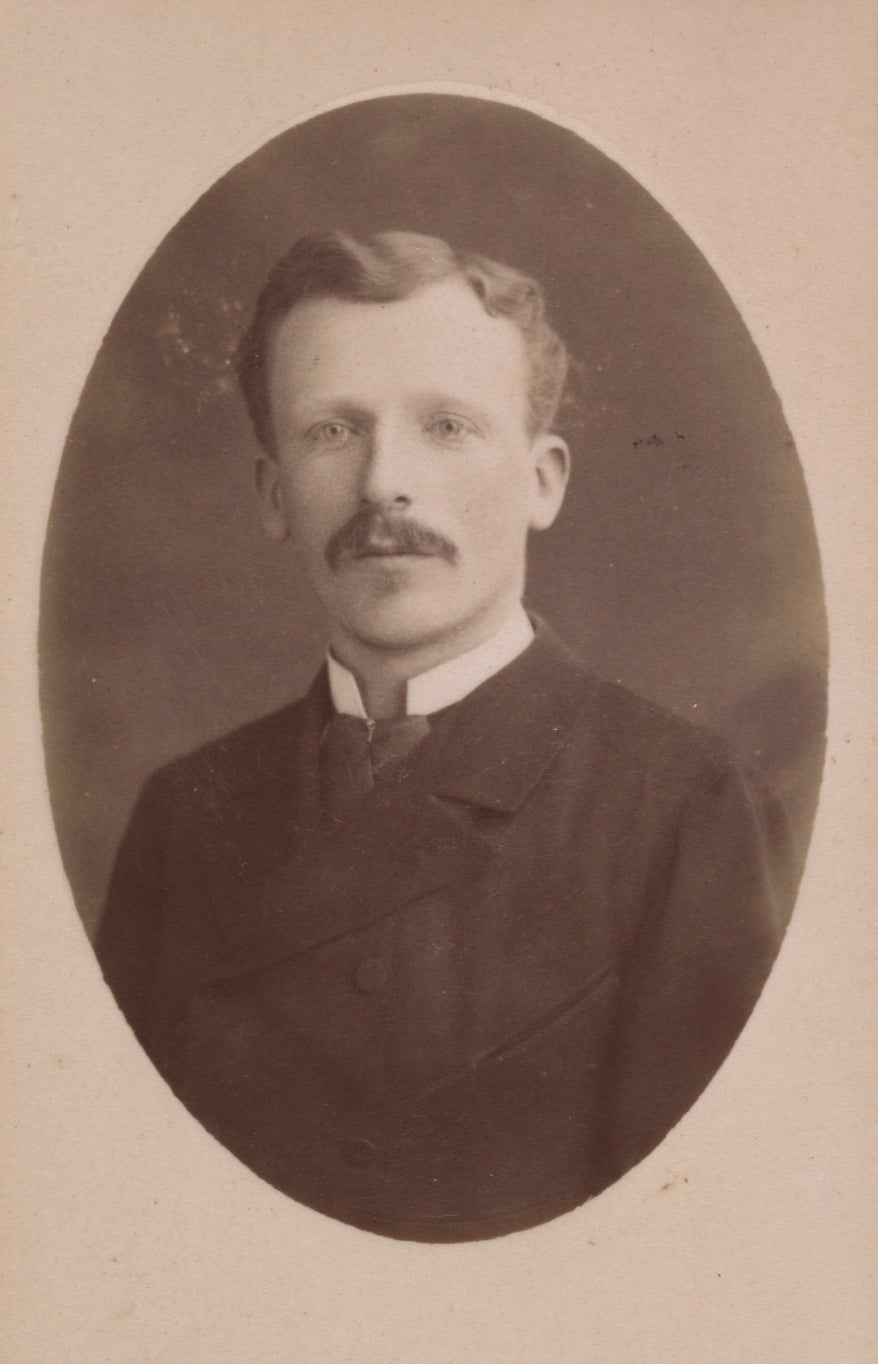

A tougher man than Theo would have dismissed this as the latest fad by a man who’d roamed from job to job and never stuck at anything. Yet remarkably, Theo had faith in Vincent’s artistic ambitions. Even more remarkably, he offered to support Vincent financially until he found his feet. In exchange for this allowance, Vincent gave Theo joint ownership of all his artworks. The idea was that Theo would sell them on his behalf.

In the long run this turned out to be the investment of the century but at the time it was a lousy deal. Theo could see that Vincent had some talent but he could also see that Vincent’s paintings would be extremely difficult to sell. Vincent was working hard and improving rapidly but his gloomy daubs of glum peasants labouring in muddy fields under darkened skies were hardly the sort of paintings you’d want to hang above your mantelpiece.

At least Vincent was suitably grateful for the lifeline his kid brother had flung him. Every month Theo sent him money, and every month Vincent wrote a long letter in return. These weren’t just thank you notes – Vincent poured his heart out. He wrote about art, religion, philosophy. He revealed his deepest thoughts. Vincent sent hundreds of letters to Theo, and though neither of them imagined they’d ever reach a wider audience, this correspondence played a key role in the creation of the Van Gogh cult.

Vincent was very lucky to have a brother like Theo. A more business-minded man wouldn’t have been willing to support Vincent. A less business-minded man wouldn’t have been able to afford it. For a while, Theo considered leaving Goupil & Cie to set up on his own, and Vincent egged him on.

In the end, Theo decided it was too risky. It was a good job he didn’t take his big brother’s advice. Without a steady income from Goupil & Cie, Theo might not have been able to afford to bankroll Vincent anymore.

In 1886, Vincent went to live with Theo in Paris, and though he proved to be the housemate from hell, constantly driving Theo to distraction, living with Theo did wonders for Vincent’s art. Theo introduced him to up-and-coming artists like Gaugin and Toulouse-Lautrec, who admired Vincent’s work. Their friendship boosted his confidence and brightened up his palette. By the time he left Paris in 1888, to move to Arles in the south of France, he’d finally become the artist we know and love today.

By now, Theo was engaged to Jo Bonger, a young teacher and translator. They married in April 1889, and in January 1890 she gave birth to a baby boy, whom the happy couple called Vincent, after his uncle (the elder Vincent was in an asylum at the time, plagued by paranoid delusions).

Rejuvenated by this news, Vincent painted a beautiful picture of almond blossom for his new nephew; a painting that now forms the centrepiece of the Van Gogh Museum’s Choosing Vincent exhibition. “He always looks with great interest at Uncle Vincent’s paintings,” wrote Jo, in a letter to Vincent, updating him about his namesake, “in particular the blossom that hangs above our bed.”

A few months later, Vincent left the asylum and moved to Auvers, a small town close to Paris. En route he visited Jo and Theo, and their infant son. “Silently, the two brothers observed the quietly sleeping baby,” recalled Jo. “Both of them had tears in their eyes.”

Sadly, Vincent only had a few months more to live. In July 1890, in Auvers, he shot himself in the chest. Theo rushed to his bedside but there was nothing he could do to save him. Vincent was 37 years old. He left Theo hundreds of paintings, many of them painted in the last few months of his life. Six months later Theo died from syphilis, aged 33. He left his brother’s paintings to his wife Jo and their little boy.

Mercifully, Jo was not infected – but that was her only crumb of comfort. Widowed, with a one-year-old child to raise and now running a boarding house to make ends meet, she could have been forgiven for forgetting all about her late brother-in-law’s unsellable paintings. Instead, she set about establishing his posthumous reputation.

“She wants to pursue her husband’s dream, and that’s what she does for the next 35 years of her life,” says Lisa Smit. “She dedicates her life to finding recognition for the work of Vincent. She starts to exhibit his work very early on.” This process reached its peak in 1905 when Jo organised a massive solo show at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. Built around her late husband’s huge collection, it remains, to this day, the biggest Van Gogh retrospective ever staged.

An equally crucial contribution was Jo’s compilation of Vincent’s letters, which she published in 1914. Thanks to these heartfelt missives, we know more about what he thought and felt than any other artist. Van Gogh’s millions of modern fans engage with him as a personality, not just as a painter; and that personality cult began with the publication of this groundbreaking book.

Jo also built Van Gogh’s reputation through judicious sales, ensuring that some of his most iconic artworks ended up in the world’s most prestigious museums. In 1924, she sold one of her Sunflowers to London’s National Gallery. “She parted with it with pain in her heart but she said it was a sacrifice for the glory of Vincent because she wanted this important institution to have an important Van Gogh painting,” says Smit.

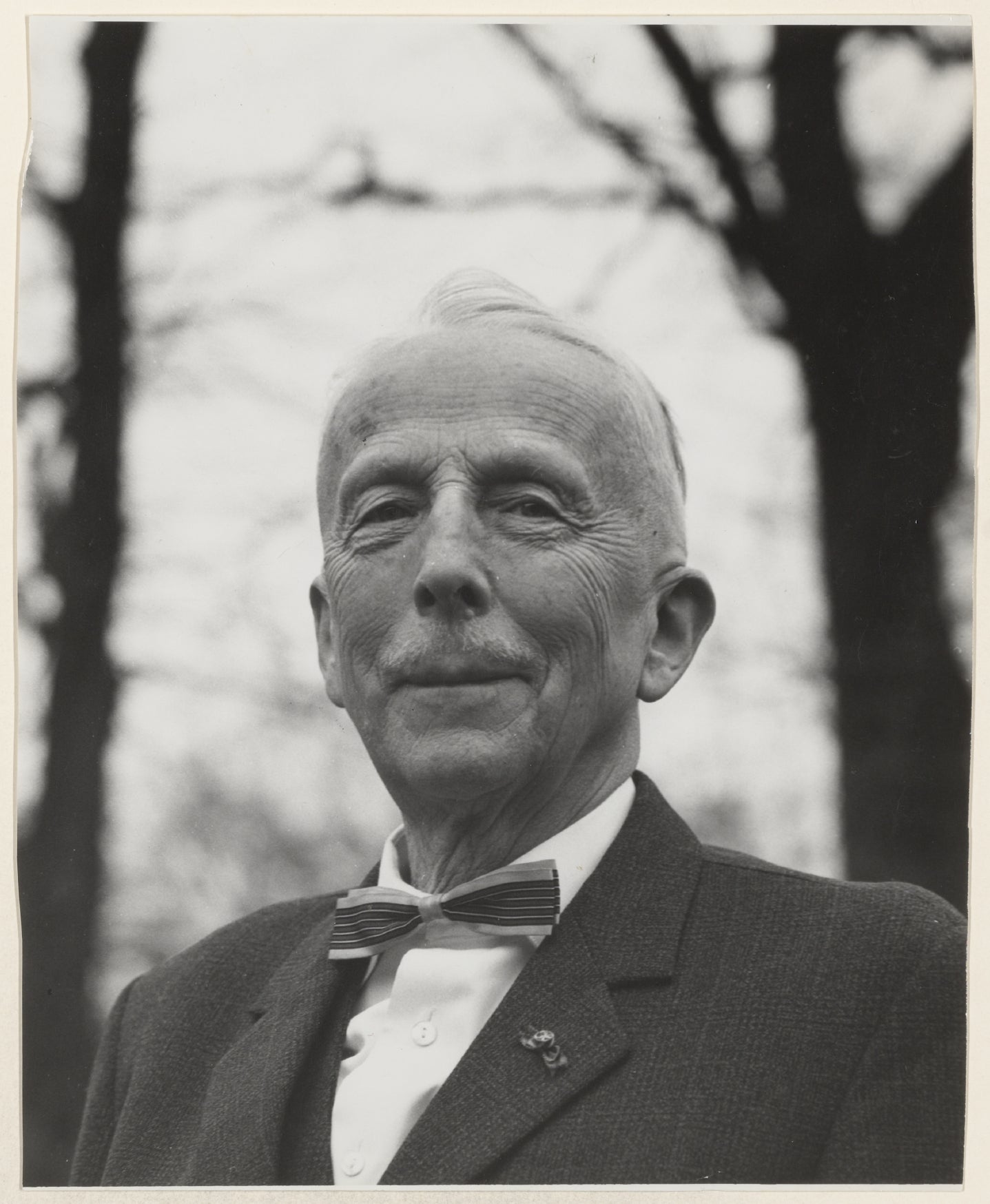

Jo died in 1925, leaving Theo’s art collection to her son – Vincent’s nephew and namesake, Vincent Willem. She’d sold a few of these paintings, to pay the bills and spread the word, but the bulk of the collection remained intact. Vincent Willem sold a few more but in 1927 he resolved to make no more sales, and in 1930 he loaned a large number to the Stedelijk.

By now, thanks to Theo and Jo, Van Gogh paintings were commanding big prices. Vincent Willem could have sold the lot and lived the high life but for him these paintings were too personal to sell to the highest bidder. Instead, he chose to put his priceless collection on public view.

Partly, this was because he’d established his own career as an engineer and wasn’t short of money. But mainly it was because he believed his uncle’s work should be seen by everyone. “He never knew his father, he never knew his uncle, but he grows up surrounded by the artworks of his uncle,” says Smit. “He could have become filthy rich but for him that was not what it was about.”

The Netherlands had remained neutral during the First World War, which safeguarded Vincent Willem’s collection, but during the Second World War Germany occupied the Netherlands, so it was hidden in a bunker in the dunes. The collection remained unharmed but Vincent Willem’s war ended tragically when his eldest son Theo (named after Vincent Willem’s father), a member of the Dutch resistance, was executed by the Nazis.

After the war, Vincent Willem retired from engineering and devoted all his time to the collection. In 1962 he transferred all these artworks to the Vincent Van Gogh Foundation, and the Dutch state set about building a new museum in which to house them, here in Amsterdam. After years of preparation, the Van Gogh Museum opened in 1973. “It’s amazing that there’s one place in the world where you can see such a large collection of his work, of all the different phases of his life,” says Smit.

Vincent Willem wanted to make the collection accessible, rather than merely preserving it, which meant building a museum with “a living and lively character”, rather than “a warehouse shunned by the public and visited only by a handful of students and experts”. He wanted a museum with a library, a lecture hall, a reception room and space for temporary exhibitions – all common nowadays but still relatively new back then. In particular, he wanted the museum to have a studio where visitors could paint and draw. “Anyone who enters the building has to feel welcome,” he said.

Thanks to his inclusive vision, the museum still feels welcoming today. A striking, futuristic building, flooded with natural light, it seems more like a municipal arts centre than a posh art gallery. When it opened, some critics wondered if there’d be sufficient demand for such a large gallery devoted to a single artist. Today, the main challenge is to escape the crowds.

However, in the end it’s all about the paintings. “Our collection history is a very moving family history,” says Lisa Smit. “Every single object you see here today comes directly from the inheritance of Theo van Gogh, the beloved brother of Vincent.”

The reason Theo’s collection is still intact is entirely due to the selflessness and foresight of his widow, Jo, and his son, Vincent Willem. It’s what makes this collection so personal and intimate. As well as 200 paintings, 400 drawings and 700 letters by Vincent van Gogh, it includes all sorts of artefacts from other members of his family. One of the exhibits in Choosing Vincent is Jo’s original diary, on show for the first time.

“We have these things because of the family connection,” says Smit. “The fact that Jo and later on her son dedicated themselves to the collection is absolutely essential to the Van Gogh Museum because that’s why such a large core collection was kept together – the biggest collection of Van Gogh works worldwide.” Would he still have become famous without Jo and Vincent Willem? Possibly, but he couldn’t have done anything without Theo.

Vincent Van Gogh created images of unrivalled power and beauty – images that move us in ways no other artist knows how to do. But none of those paintings would be here today without the three people who supported him: his sister-in-law, his nephew and his faithful brother, Theo.

As Vincent Willem said, at the opening of this magnificent museum, five years before he died: “Our goal is to make people who are free inside.” It’s a goal he shared with his uncle – a man he met just once when he was still a baby, sleeping beneath that picture of almond blossom, painted for him as a birthday present by the most extraordinary artist of modern times.

Choosing Vincent is at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until 10 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments