The story of the Salzburg festival that inspired Edinburgh

The Salzburger Festspiele, founded after the First World War, was set up to reunite old enemies through their love of performing arts. William Cook tells its tale

Here on the leafy outskirts of Salzburg, in the shadow of its rugged castle, there is a building that changed the course of European culture, and inspired the Edinburgh Festival, the biggest arts festival in the world.

Film buffs will recognise Schloss Leopoldskron as the von Trapp residence in The Sound of Music, but the most significant event in the history of this palatial house occurred at the end of the First World War, when it was bought by Austrian impresario Max Reinhardt. It was here that Reinhardt hatched the idea for the Salzburger Festspiele, an international festival designed to reunite old enemies through their shared love of the performing arts. Reinhardt described this pioneering project as “the first work of peace.”

Reinhardt’s scheme was so successful that it’s since been copied throughout the world, most notably in Edinburgh after the Second World War. In Edinburgh as in Salzburg, the aim was to bring together former foes after years of bloody conflict, as performers and spectators, to celebrate their common heritage in a place where they could also let their hair down. Today Edinburgh is the behemoth, but Salzburg was the prototype, and its colourful, stormy history mirrors the triumphs and calamities of the last century.

The centenary of the Salzburg Festival, in 2020, was overshadowed by Covid, and although the 2021 festival went ahead, many international visitors stayed away. This is the first year since 2019 that foreigners can attend without restrictions, and so last week I went back there again, ahead of this summer’s Festspiele, to take a closer look at the story of the festival that helped to change the world.

What is it that makes the Salzburger Festspiele so exceptional? What can the story of its origins teach us about the world today? With war raging again in Europe, art can sometimes seem like an extraneous luxury, but that’s not how people saw it during the First or Second World War. In 1947, the Edinburgh Festival helped to forge a new idea of Europe, and it can trace its roots back to Salzburg in 1920.

When Max Reinhardt moved into Schloss Leopoldskron, in 1918, his native Austria was in a state of crisis. His homeland was facing imminent defeat in the First World War, alongside Germany, and the consequences were bound to be severe. Sure enough, the subsequent Treaty of Versailles stripped the Austrian Empire of the vast majority of its territory. It lost huge tracts of land to Italy, Poland and Romania, and the newly created states of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Austria was massively reduced.

Reinhardt was an internationalist, not a nationalist. While other Austrians railed against the Versailles Treaty, Reinhardt sought to re-establish cultural ties with these lost lands, and with Austria’s First World War adversaries. Before the First World War, the Austrian Empire had been polyglot and cosmopolitan. Its reactionary ruling class had brought about its ruination, but it had also been a bastion of creative innovation. A Viennese Jew who’d made his name in Berlin as a radical theatre director, Reinhardt personified the progressive side of Austrian culture, and it was this outward, forward-looking attitude that he brought to Salzburg in 1918. Schloss Leopoldskron became a rendezvous for artists and intellectuals, and in 1920 it became the springboard for the first Salzburg Festival.

“The heart of the heart of Europe,” as Reinhardt put it, Salzburg was an ideal location for an international arts festival. An important pitstop on one of the main trade routes between northern and southern Europe, it had always looked beyond its borders – Bavaria is only a few miles away. Until 1816, it was an ecclesiastic city-state, ruled by a succession of Catholic bishops, who cultivated art and music as a bulwark against the Reformation. Mozart for example, who was born and raised here, was one of the beneficiaries of their patronage.

Like virtually every city in the Third Reich, Salzburg was bombed during the Second World War, and when the US army occupied the city, in 1945, around a quarter of its buildings had been destroyed

Those bishops rebuilt Salzburg in ornate Italianate style, a cluster of domes, spires and piazzas – an Alpine version of Vatican City. When Reinhardt arrived, it had only been Austrian for a century, granted to Austria in the reconfiguration of Central Europe after the Napoleonic Wars. Supported by the composer Richard Strauss and the playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Reinhardt resolved to transform the entire city into a stage.

Right from the start, these three founders were profoundly idealistic. Von Hofmannsthal called the Festspiele “a matter of eminent political, economic and social importance.” Reinhardt declared that the arts were more than mere decoration, an essential part of life, as fundamental as food. Looking back on those heady days it might be easy to scoff at such idealism, but it was this idealism that drove them on and made the Festspiele so successful.

The first Salzburg Festival began with Jedermann, Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s modern version of Everyman, a medieval morality play, performed in the cathedral square – this show was such a hit that it’s been performed there virtually every year ever since. In 1921, orchestral music was added to the programme. In 1922, opera completed this rich mix. In 1925 an imposing new concert hall, the Festspielhaus, was built especially for the festival. During the next decade, the Festspiele went from strength to strength.

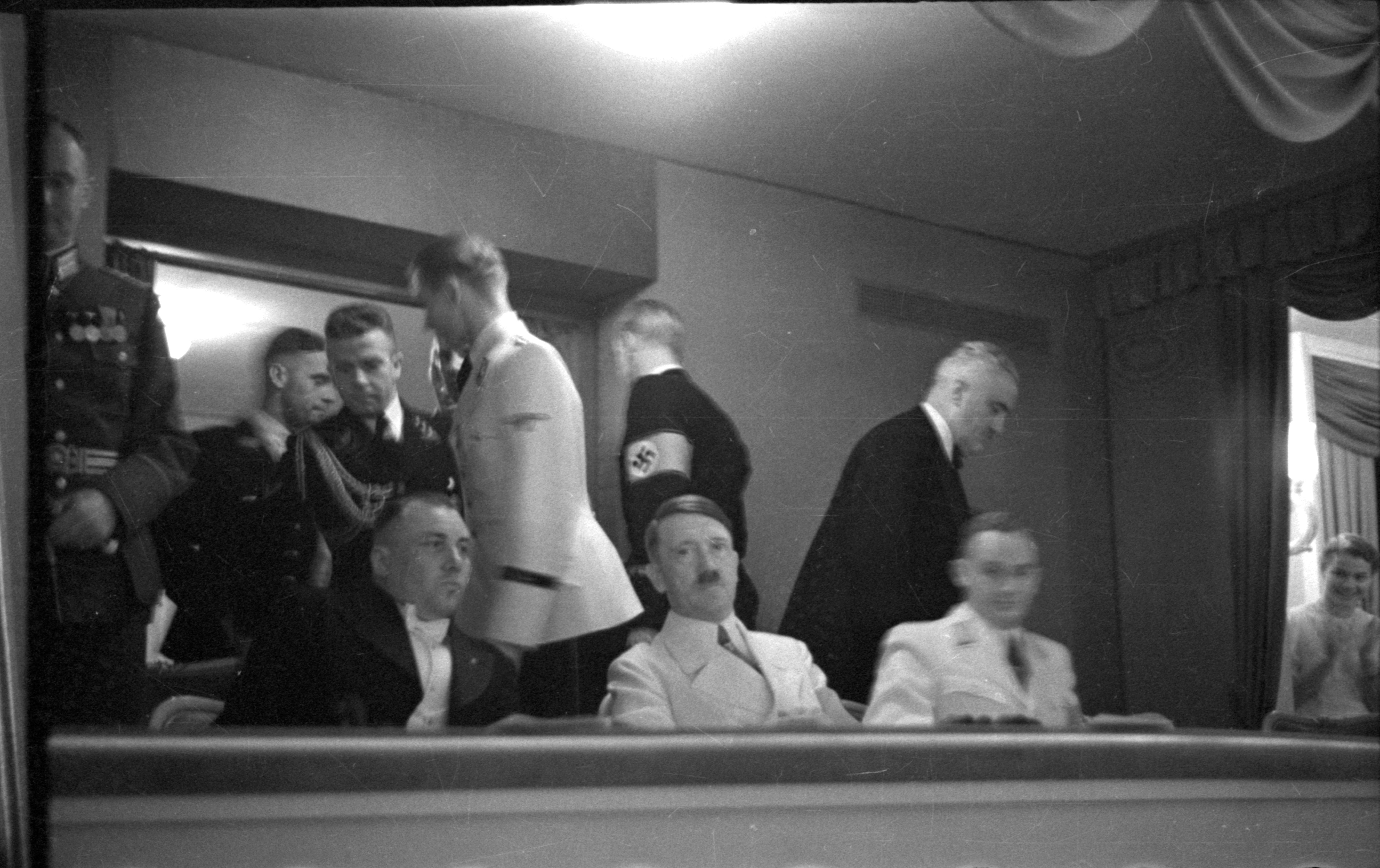

By the mid-1930s, the Salzburg Festival was firmly established as Europe’s leading showcase for orchestral music and classical theatre. Then as now, the emphasis was on established classics rather than new work, but with Europe’s most innovative directors and conductors in charge, there was nothing fuddy-duddy about it. The 1936 festival even featured a performance by the von Trapp Family Singers, later immortalised in The Sound of Music. And then, in 1938, Adolf Hitler marched into Austria, and everything changed.

Since its main focus was traditional orchestral music, a genre cultivated by the Nazis, the Salzburg Festival was able to continue, but the Nazi restrictions were still brutal. The modernist murals in the Festspielhaus were painted over. Works by Jewish composers, such as Mendelssohn, were banned, Jewish performers were exiled, Reinhardt’s Salzburg home, Schloss Leopoldskron, was confiscated by the Nazis, and Reinhardt was forced to emigrate to the USA, where he died, in 1943. Hijacked by the Nazis, the festival continued during the war, a shadow of its former self, until Josef Goebbels banned it, in 1944, in the aftermath of the failed attempt to assassinate Hitler.

One unexpected consequence of this Nazi stranglehold was that performers fleeing from Salzburg took the spirit of the Festspiele with them. The Lucerne Festival, in Switzerland (now one of the world’s leading festivals of orchestral music), was set up in 1938 by refuseniks from Salzburg. Many Jewish musicians found sanctuary in the United Kingdom. The impresario Rudolf Bing, a Viennese Jew who'd fled from Germany to Britain, was the co-founder and first director of the Edinburgh Festival. “My mind kept returning to the sight of the castle on the cliff at Edinburgh,” he said. More than any other British city, it reminded him of Salzburg.

Like virtually every city in the Third Reich, Salzburg was bombed during the Second World War, and when the US army occupied the city, in 1945, around a quarter of its buildings had been destroyed. With food and shelter scarce, and the city flooded with refugees from eastern territories seized by Stalin, you might have thought that reviving the Festspiele was the last thing on anybody’s mind. Yet remarkably, the Salzburg Festival resumed that summer, only a few months after VE Day. After the Nazification of Austria, which had contaminated every avenue of daily life, the Americans recognised the importance of restoring Salzburg's liberal culture. The resumption of the Salzburger Festspiele was a crucial component of denazification.

Thanks in no small part to that benevolent, far-sighted liberation, the Salzburg Festival became an annual event again, and it’s been going strong ever since. The dominant figure of the postwar years was the great conductor Herbert von Karajan, a Salzburger born and bred, who was artistic director of the festival for over 30 years, from 1956 until his death in 1989. Since then the festival has become less traditional and more experimental, but quality remains its main ethos, rather than experimentation for its own sake.

Reassuringly, for anyone who finds modern classical music a challenge, this year’s programme includes plenty of familiar favourites: Mozart’s Magic Flute, Verdi’s Aida, Handel’s Messiah, and Daniel Barenboim conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. However, there are lots of new names too. The Salzburger Festspiele may be traditional, but it’s not conservative. And like the Edinburgh Festival, it’s also spawned a separate, unofficial fringe. You don’t need to buy a ticket for the Festspielhaus to enjoy the festivities. There are musical and theatrical events all over town, in fringe venues and even on the streets.

Today, thanks to Salzburg, the world is full of arts festivals, so why is this one still so special? Perhaps its extraordinary density has a lot to do with it

But how do the locals feel about it? Of course, it’s fantastic for visiting artists and aficionados, but what about the folk who actually live here, who aren’t full-time arts professionals or paid-up members of the cognoscenti? To find out, I met up with Gottfried Seer, a retired Salzburger who plays a small but crucial role in the perennial performance of Jedermann. He only has one line, one word in fact, which he bellows from the church tower, a voice from the heavens, calling Jedermann to judgement. He left me in no doubt how much the Salzburger Festspiele means to him, and other locals like him here in Salzburg.

“It’s a timeless classic,” Gottfried tells me, over coffee in Hotel Goldgasse, an ancient Gasthaus in Salzburg’s medieval Altstadt. “It’s one of the most beautiful venues in all of Austria. Part of this play is about faith, and when the actors are on stage, they have the cathedral behind them, so God Almighty is behind them.” He's been playing the role for over 20 years, and he’s seen the show change since he first took part. “Back then, the performances were baroque,” he says. “Today, it’s more modern - the text captures you from the first line.”

As Gottfried explains, to some extent the Salzburger Festspiele has been a victim of its own success. The opening night is a grand affair - celebrities stepping out of limousines in ballgowns and dinner jackets – and since these are the images that end up in the papers, a lot of people assume the entire festival must be a red carpet event. “The festival always had a reputation for being for super-rich people, but the more I got into it, the more I realised there are so many concerts and so on that you can see for very little.”

Like the Edinburgh Festival, this performing arts festival has also invigorated other artforms. Fine art used to be a poor relation here. Now it’s a star player. Salzburg is home to one of Europe’s leading commercial galleries, Galerie Thaddaus Ropac. It also boasts a thriving modern art museum, the Museum der Moderne. On my last day in Salzburg I went along to the opening of the museum’s new show, Nervous & Angry. A riveting exhibition featuring artists from George Grosz to Käthe Kollwitz, all drawn from the museum’s own collection, it’s a brilliant example of how this compact city – just 150,000 inhabitants – has become a centre of all the arts.

Afterwards, I sat down with the museum’s director, Thorsten Sadowsky, and asked him how the Festspiele has affected Salzburg as a whole. “The Salzburg Festival is very important for Salzburg,” he says, but although he works in cooperation with the festival, his museum provides a refreshing contrast – more avant-garde, more provocative, in much the same way that Edinburgh’s Fringe provides a contrast to the official international festival. “It’s not our job to be part of a conservative and well-established artworld.”

Today, thanks to Salzburg, the world is full of arts festivals, so why is this one still so special? Perhaps its extraordinary density has a lot to do with it, and Thorsten thinks this may be the case. “You have so many cultural events, and you can walk from one to another – you don’t need to use a car,” he says. “That is really unique, I think, in Europe, that we have that concentration of culture in such a small place.” This is a baroque metropolis, a place where Mozart would still feel at home. You bump into people as you walk around. You don’t need to plan ahead.

Today Salzburg is a festive city all year round, but the summer Festspiele still feels different, a time when Salzburg becomes what Austrians call a “Weltstadt,” a world city. “You have an international audience,” says Thorsten. “People come from every part of the world – we have people from China, from the Far East, from the United States, from all parts of Europe.” Max Reinhardt would have been thrilled to see it. If only he was still around today.

And what became of Schloss Leopoldskron? Well, today it’s the home of Salzburg Global Seminar, a non-profit organisation that hosts conferences on a wide range of topics, from culture to geopolitics. Like the Salzburg Festival, it was founded to foster international understanding after a world war – the second in this case. The Schloss has been beautifully restored and the highlight is Reinhardt’s exquisite wood-panelled library. Reinhardt left quite a legacy – the Salzburg Festival, the Edinburgh Festival – but for me, this precious library is his most intimate monument and the place where I feel closest to this extraordinary, visionary man.

William Cook was awarded the Johann Strauss Gold Medal for his reporting from Vienna. The Salzburg Festival (www.salzburgfestival.at) runs from 18 July to 31 August. For more information about Salzburg and the surrounding region, visit www.salzburg.info or www.salzburgerland.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks