‘Well, f*** it. Life’s short’: Tracey Emin isn’t holding herself back anymore

It’s been two years since the artist was diagnosed with cancer, but now she’s back creating again. She speaks to William Cook about her fight, the death of her mother, and her brand new works

At Jupiter Artland, a sculpture park on the green edge of Edinburgh, Tracey Emin is presenting her latest artwork to the press. Journalists crowd around her, photographing her from every angle, but Tracey isn’t fazed. She laughs and jokes with them, answering every question with disarming honesty. You’d never guess that not so long ago she underwent major surgery for bladder cancer, leaving her too weak to paint.

That was back in 2020, but it took her a long time to regain her strength, which is why this artwork feels like such a triumph. Titled, I Lay Here For You, it’s a huge bronze sculpture of a reclining female nude. She’s lying on her front, face down, her legs and buttocks slightly raised. Is she in the throes of sexual ecstasy? Has she been sexually assaulted? Or is she merely sleeping? Like a lot of her work, it’s both alluring and disturbing. It’s this ambiguity which gives this sculpture its strange power.

“I’ve been wanting to do it since 2010, and I’ve been working up to it and working up to it,” she says. “My mum dying, it kind of gave me this extra confidence to do it ... When she died I felt so bereft that it was like: ‘Well, f*** it. Life’s short. Go for it. Do it.’ Because if I mess it up, well, I mess it up. It’s OK, it’s alright. It was like my mum sort of saying: ‘Go on Tray, do what you want to do – don’t hold yourself back.’”

Sculpture is a relatively new medium for her, but it’s one she relishes. “Artists that move from one discipline to another – painting, sculpture, printing, film, whatever it is – are always somehow looked down upon. People are kind of condescending towards it. But I think, as an artist, working in whatever medium I like, is fantastic, because I’m always excited.”

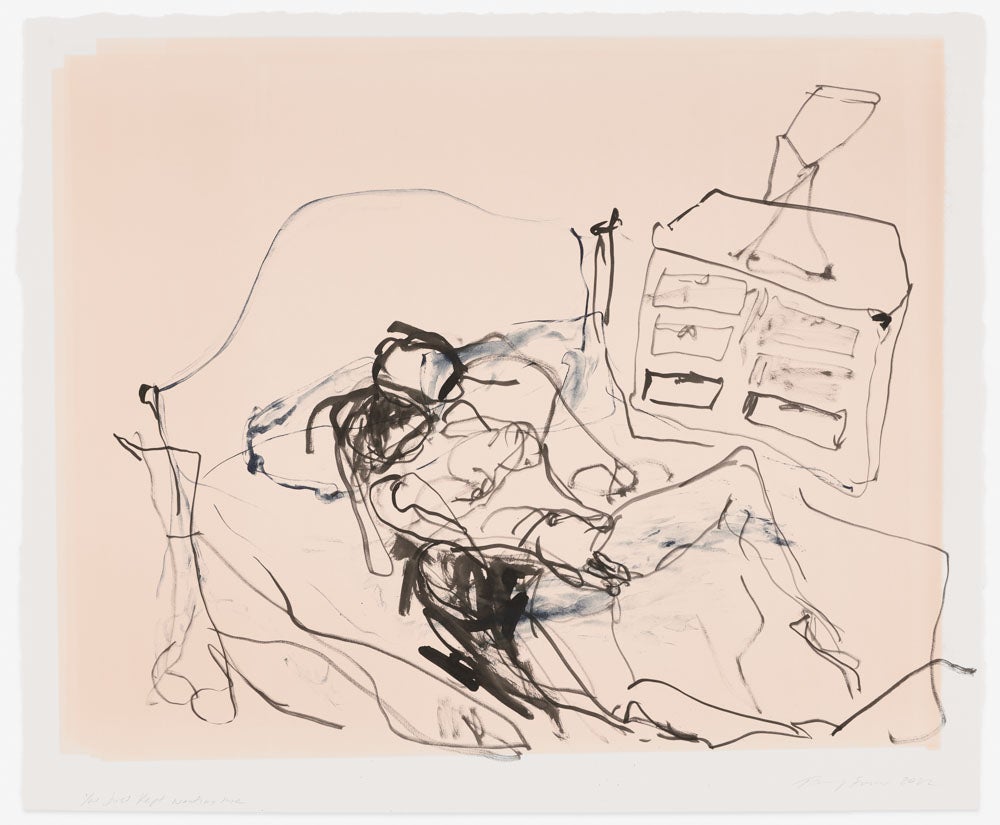

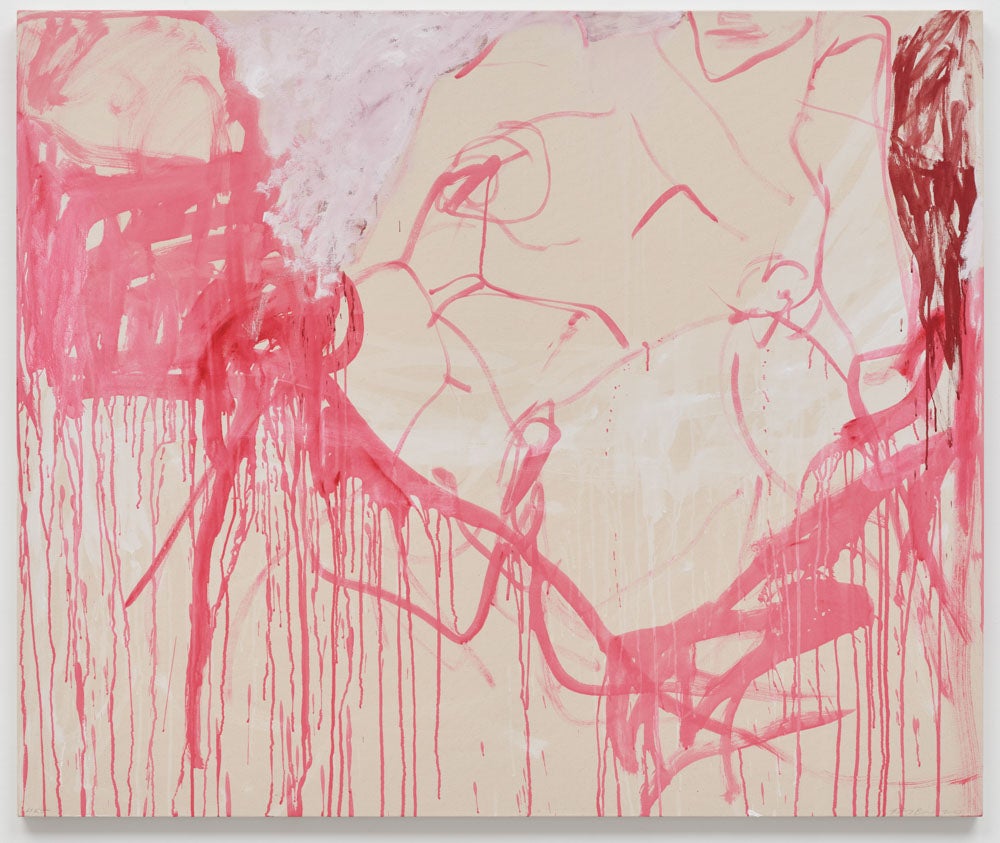

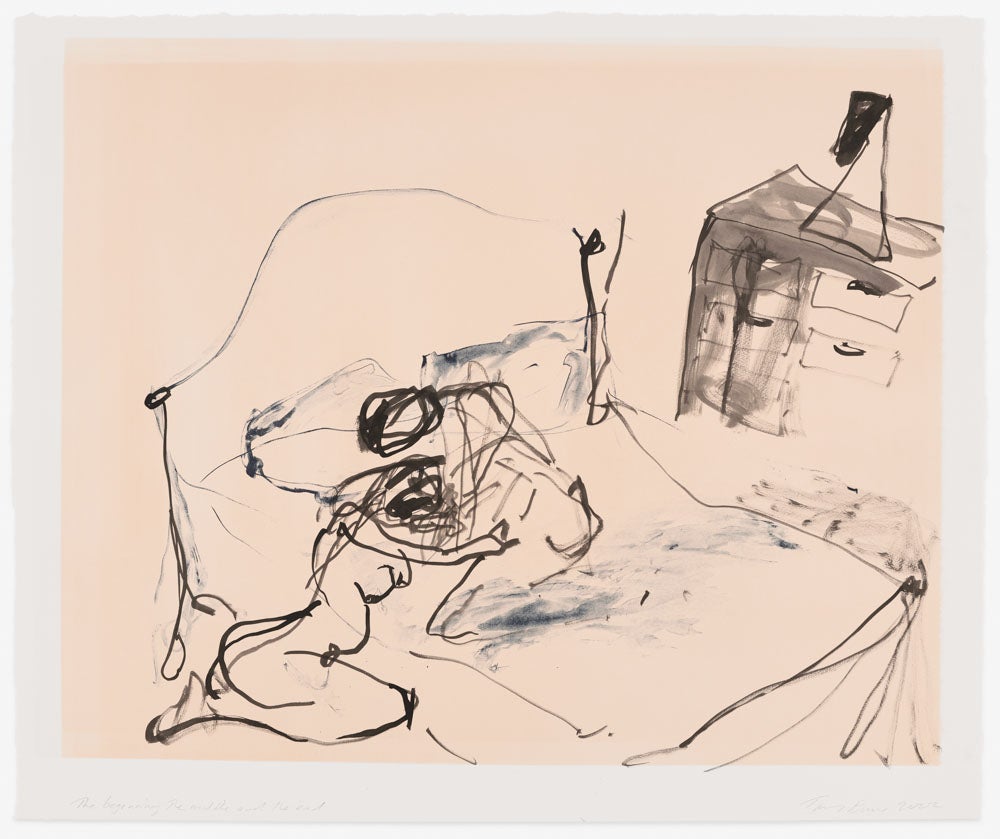

I Lay Here For You is the biggest artwork in a powerful new exhibition which reaffirms Emin’s position as one of the leading artists of her age. A lot of these works are overtly sexual, but they’re sensitive and complex rather than gratuitously explicit. With economy and grace, they capture the agony and ecstasy of sexual passion. The titles are poetic: You Just Kept Wanting Me, I Held You In Your Darkness, Of Course I Was Hurt and It Was Always About Love.

Words have always played a big part in her work, most notably in her iconic neon signs like I Want My Time With You (2018), which greets countless travellers every day, as they arrive at London’s St Pancras Station. For Tracey Karima Emin, CBE, RA, it’s also been quite a journey, from dropping out of school with no qualifications to becoming one of Britain’s most prominent and important artists.

She was born in Croydon in 1963, along with a twin brother, Paul, and raised in Margate. Her mother, Pam Cashin, was unmarried – her father, Enver Emin, a Turkish Cypriot, was married to someone else. Her teenage years were turbulent and she was sexually assaulted when she was 13. This was chronicled in her heartbreaking film, Why I Never Became A Dancer – a brave and shocking Bildungsroman, a Roman-a-Clef for the Costa-del-Dole generation.

Damaged but undefeated, she dropped out of school and moved to London. Her salvation was being accepted, despite her lack of qualifications, at Maidstone College of Art. She graduated with a first-class degree in fine art and then did a master’s in painting at the Royal College of Art.

She loved her time at Maidstone but found the RCA frustrating, and left with a conviction that her art was unoriginal. “My work was s***,” she told Melvyn Bragg, in a riveting and candid South Bank Show. “It was just like a copy of every German Expressionist you can imagine.” Ironically, her new show, at Jupiter Artland, is strongly reminiscent of German Expressionism, but there’s nothing derivative about it. Yet, at the time, her analysis was sound. She had to abandon painting for a while in order to find her own voice.

This is here forever and it’s part of an affirmation of who I am as an artist. It’s mine, I created this and I’m never going to abandon it. Part of me is always going to be there

“The idea of being some kind of bourgeois artist, making paintings that just got hung in rich people’s houses was a really redundant old-fashioned idea that made no sense to the times that we were living in,” she told Bragg. Instead, she turned to other media – film, photography, found objects – and focused on her own life.

This provocative process culminated in 1995’s Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963 - 1995, a tent adorned with the names of everyone she’d slept with (rather than had sex with), including family members as well as lovers, and two aborted fetuses. She told Bragg: “People were ringing me up and saying: ‘Why have you put my name on your tent? You shouldn’t have done that.’ And I said, ‘well, you shouldn’t have f***ed me then, should you?’”

Her most famous, or perhaps infamous work, My Bed (1998), took this process to another level. Rather than painting a picture of her bed, she simply exhibited the bed itself, complete with stained sheets, soiled underwear and discarded condoms. This was exactly how it had appeared after she’d spent four days in it, in a depressive state, and so this was exactly how she presented it. The media regarded it as outrageous, but it was actually part of a long tradition. Just as German Expressionists would have understood her painting, so the Dadaists and Surrealists would have understood this daring objet d’art.

The popular press pigeonholed her as a “Young British Artist,” but if that crude and clumsy label was ever applicable it’s now a generation out of date. She’s no longer a fashionable young rebel, a symbol of “Cool Britannia”. Today she’s a mature artist whose work transcends time and place. Timeless and international, her more recent work feels a world away from the rebellious Britart of the 1990s. She has more in common with Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele than any of the YBAs.

Like Emin, Munch and Schiele were fearlessly intimate and revelatory: Munch painted his dying sister; Schiele drew his dead wife. Emin portrayed her recent, life-threatening illness with the same raw, heartfelt candour that she applied to her traumatic sexual experiences. And now recovery has granted her a whole new lease of life.

After the photo shoot and after the other journalists dispersed, I sit down with Emin for a one-to-one interview in the handsome Jacobean house that stands in the middle of the sculpture park. She looks fragile, her voice sounds frail, but her eyes are full of laughter. I warm to her straight away. I’ve never met her before so I can’t say how much cancer has changed her, but she’s still got that engaging, crooked grin I’ve seen in a thousand photos. She talks passionately about art and artists. She’s completely open and utterly sincere.

We begin by talking about one of her heroes, the late great Louise Bourgeois, whom Emin worked with for a while. Like Bourgeois, Emin’s work explores the most intense and painful aspects of human existence, through all sorts of media, so it’s no surprise to learn that Bourgeois has been a major inspiration. “She just did whatever she felt like doing.” And so does Emin.

“When my mum died, in 2016, I’d planned that year to have a sabbatical, not to do any shows, not to do any interviews, not to do anything, to make no commitments, have no pressure, and spend a year just working and thinking, but it was the year that my mum was really ill. She had the same cancer that I had, bladder cancer, and so I was painting all the time and working and constantly visiting my mum.” When she died, Emin resolved to make the most of things, and not hold back. “This was supposed to be my year,” she thought. “I’ve got to do something for myself.”

That something was sculpture. “My mum’s death definitely inspired all the small figures that I made.” From those small figures, bigger figures grew. Monumental sculptures like I Lay Here For You articulate a determination to leave a legacy, a determination that was heightened by her own harrowing illness. “Those giant bronzes, they’re not going anywhere. They’re going to be here for a thousand years.”

So how’s her health? Her answer is typically frank and forthright. “Having a urostomy bag, people say, ‘it’s just a bag.’ It’s not just a bag. You don’t sleep. All your core muscles completely collapse. You have to go to the loo – sometimes not for an hour, sometimes every 10 minutes. You can’t go on a long journey without plugging in a large night bag. There’s lots of things that change in life.” And change is never easy. “I’m not strong like I used to be, at all,” she says. “When I was just like a waif, just lying in bed, when I wasn’t moving, on morphine all the time, it was easy because I wasn’t going anywhere, it didn’t matter, but now I need to be stronger.”

Making art is an athletic process, especially the way Emin makes it – hurling paint at canvases, wrestling with clay. “Everything I make is made by me in my studio. That should be a given, that should be obvious, but for a lot of artists it’s not like that.” She’s never had an army of assistants. She’s always been a hands-on artist, rolling up her sleeves, getting down and dirty, and this made it particularly hard for her to get started again after the cancer had abated. “I only started painting properly a few months ago,” she says. “Now, physically, I’m well enough to work. I mean, put it this way: a year ago, I couldn’t sit upright in a chair for more than half an hour.”

So has anything good come out of it, or has it just been an awful hindrance? “Loads has come out of it. Tonnes and tonnes of positive things. Like, I don’t put up with any bullshit anymore, at all – number one. Number two: I stopped drinking, which is really brilliant. That’s given me a major amount of clarity in my life. Being sober for nearly two years is pretty life-changing, I reckon. It’s been really good. I was smart before – now I’m razor sharp.”

It’s inspiring to hear her describe how she’s found a way forward through this trauma, how sobriety brings clarity and how “losing a few bits of your body” doesn’t have to spell defeat. “The cancer’s really bad, the bladder thing’s really awful, the major surgery was really terrible, but I’m so much happier than I was,” she says. “I feel so much better than I did.”

For her, the biggest blessing is being able to work again. “I love it. I love the dialogue with the painting. I like the feel of it. I like the unexpected with it. I like pushing myself or unpushing myself, learning when to stop, when to start. It really stops you from being lonely. Sometimes when I’m in London, in my studio, I fall asleep on the sofa with my paintings, and I always think they like it. It seems silly, but I think they like it.”

I think a lot of things in my life, whether it be rape or whether it be teenage sex, sexual abuse, whatever those things are, lots of people have to go through this hell – and they have no one there to help

She feels a similar connection with the sculpture that she’s installed here today. “This is here forever and it’s part of an affirmation of who I am as an artist,” she tells me. “It’s mine, I created this and I’m never going to abandon it. Part of me is always going to be there. It’s like being a mum.”

She’s been so generous with her own experiences, exposing all sorts of things that most of us would never dare to share, yet this approach has annoyed a lot of people, mainly men. “Being Miss Emin is her core activity,” complained the art critic Brian Sewell. “‘Look at me, look at me!’ she barks.” Sewell likened her to a “fraudulent medieval marketer of relics,” but her work was no more self-absorbed than that of countless male artists, past and present. “They were all making work about themselves and their experiences.” However, when a female artist does it, men feel far more threatened.

“A lot of people think that my art’s been about narcissism and being selfish,” says Emin. “For example, take abortion – what’s happening in America now. Suddenly, which is good, all these women are making art about abortion, being politicised and everything – I’ve been making work about it for the last 35 years.

“Instead of people saying, ‘oh wow, she’s making this really strong political point – she’s actually speaking up on a subject which is taboo,’ I actually got vilified for it, as if, ‘Oh, she’s moaning about her abortions.’ No, I wasn’t. I was talking about what it’s like to be a woman when you’re faced with that decision. What do you do? And I think a lot of things in my life, whether it be rape or whether it be teenage sex, sexual abuse, whatever those things are, lots of people have to go through this hell – and they have no one there to help them. They have no one there to confide in or talk to or relate to or whatever. If you walk into a museum and you see an artwork about abortion that I’ve made – and you can stand there and say to your friend, ‘I’ve had an abortion,’ or, ‘I need to have an abortion,’ and you can open up and talk about it, it’s going to make it so much easier.”

Her work has provided comfort and reassurance for countless people, but have these revelations cost her something? “It’s cost me lots,” she concurs. “In terms of relationships I’m not the luckiest in love – I don’t have children, I don’t have a family.” She’s sacrificed her privacy, the right to a secret inner life. However, her illness has helped her focus on what she does have, and what she wants. “Being so unwell, that made me sharpen up and think about what I do need, and what I want for the rest of my life.”

One of the things she’s doing now is opening her own art school in Margate. “If you’re a mum, you do things for your kids which benefit them, in terms of education and the future,” she says. “Just because I don’t have my own children doesn’t mean to say that I’m not going to take responsibility for the future in some way. And now I’ve worked out a way that I can do that, I feel so much better because it means that I’m going to be connected to what’s happening.” She likes the idea of growing old there. “I’ll be kind of looked after by people: ‘Oh, there she goes! Trace, d’you want a hand with your shopping?’”

On the night her mother died, in Margate, she drove down from London in the small hours, but instead of going straight to the hospital, she drove to her new studio. “I drove around this building thinking: ‘What am I doing? She could be dying right now! What am I doing?’ And I knew what I was doing. When my mum died – I knew she was dying – there would be no reason for me to go to Margate, only going back to my past: this is where I used to live, this is where my mum used to live, this is where I grew up. And I wasn’t happy with that. So I knew, from that moment, I was going to make some kind of investment in Margate.” It was an emotional investment too. “I needed to, it was part of me – Margate was never bad to me, ever. It wasn’t Margate.”

Today Margate is a very different place from the town that she grew up in. “Margate now is so f***ing cool!” she says. “Big international newspapers want to do interviews with me – not about my art, but about Margate!” She’s not blind to the social problems, all the people living below the poverty line. “A lot has got to change there and a lot has got to happen, and it is happening.” Her presence there is part of that sea-change. Having grown up, a bit too fast, on Margate’s Golden Mile, it feels fitting that she’s now been made a freewoman of the town that made her. “I was really bowled over. It was a real civic ceremony, everyone clapping. The mayor was there and all of that stuff, and it was so sweet and it was so nice.”

So has her relationship with Margate changed? “It’s like a love affair,” she replies, with a smile that lights up the room. “It’s like being in love with the same person, and your relationship changes, for better or for worse, or whatever, and you stick with them. Margate’s got a neon up of mine and it says, ‘I Never Stopped Loving You’, and it’s so appropriate because I didn’t.” As we say goodbye, I realise that’s what makes her art so special. It never shies away from pain and suffering, but above all, it’s about love.

I Lay Here For You is at Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh (www.jupiterartland.org) until 2 October 2022

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks