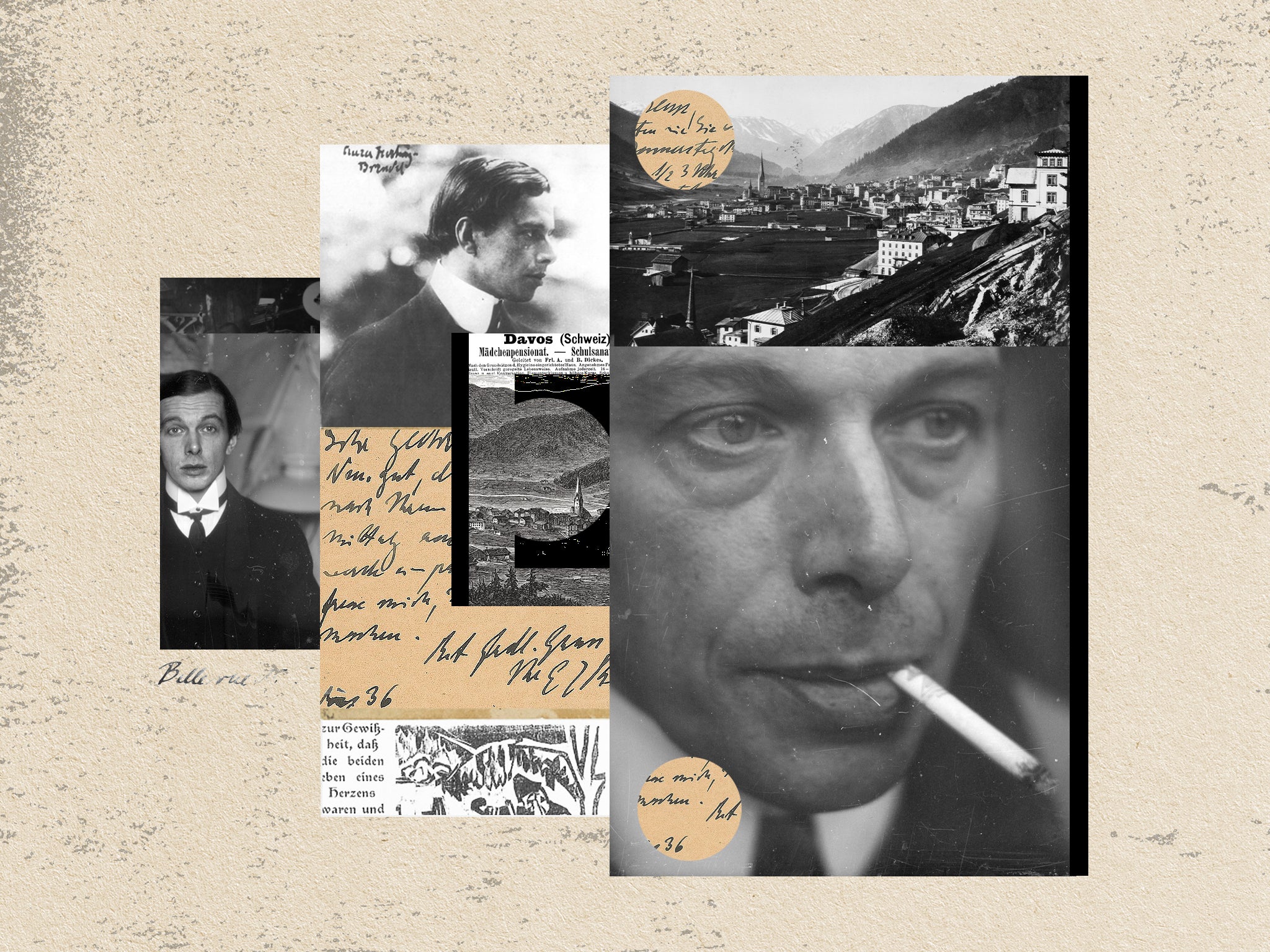

How Davos became home to one of the most important artists of the 20th century

Better known for the World Economic Forum, Davos also held an important place in the heart of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, the painter who helped pave the way for German Expressionism, writes William Cook

Here in Graubünden, in the most spectacular part of Switzerland, the inhabitants of Davos are bracing themselves for an invasion. This week, for the first time since Covid, hordes of business leaders and politicians will descend on this pristine Alpine resort for the World Economic Forum. But there’s another side to Davos, which is far more interesting than this geopolitical shindig. This isn’t just a rendezvous for jetsetting CEOs and politicos. It’s also the adopted home of one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was a pivotal figure in art history – the leader of Die Brücke, that groundbreaking group of artists who kickstarted German Expressionism during the heady years before the First World War. Die Brücke shaped the course of modern art and Kirchner was the most talented artist among them. His role in this influential movement is acknowledged by art historians, but most accounts of his career end in 1917, when he came to Davos. Kirchner spent half his adult life in Davos. He made more artworks here than anywhere. So why has the 20 years he spent here been reduced to a mere footnote in the history of western art?

For a long time, I assumed Kirchner had painted nothing in Davos during those 20 years, or at least nothing of any worth. It was an easy mistake to make. Art historians, like the rest of us, are suckers for a simple story: Kirchner’s edgy Berlin paintings anticipated the horror of the First World War, the creative chaos of the Weimar Republic and the tyranny of the Third Reich. That was the way the story of German Expressionism was always told, in Britain at any rate. It was a tale of doom and gloom. That the leading light of this movement went to Switzerland and painted exuberant mountain landscapes for 20 years didn’t fit this simplistic narrative. Far easier to skip that part, and pretend it never happened.

However during my travels around Germany, I kept coming across pictures that Kirchner had painted here in Switzerland, and I was blown away by their honesty, their beauty, their intensity. Why had I never come across these paintings before? Finally, in 2014, I made my way to Davos to see the biggest collection of Kirchner’s paintings, in the Kirchner Museum, the only museum in the world devoted to his work. I was amazed by what I found. The three houses where he lived and worked were all still here, and as I made my way from house to house, an extraordinary tale emerged. Kirchner’s time here was no mere epilogue. It was a story full of incident, which reflected the history of Germany and Switzerland between the wars.

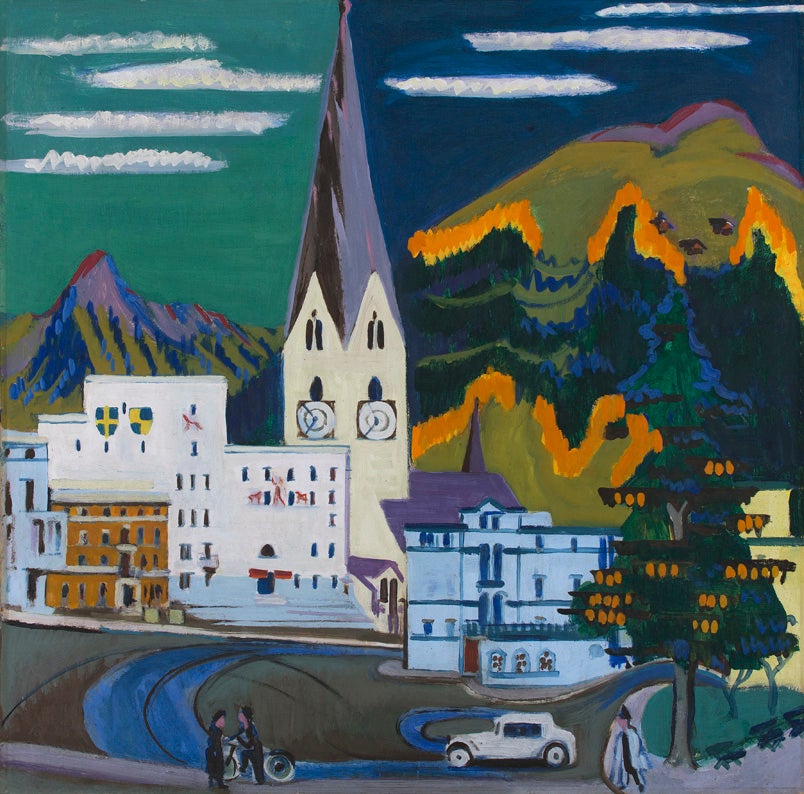

“This part of Kirchner’s oeuvre is not very familiar to the mainstream audience,” says Katharina Beisiegel, director of the Kirchner Museum, as she shows me around this sunlit gallery. “They’re fascinated by the landscapes, by the painting style he developed here.” These paintings are so different from the pictures he painted in Berlin before the First World War. While other German artists returned home and recorded the suffering of their defeated Fatherland, Kirchner came to Switzerland and painted a land untouched by war.

Kirchner came to Davos in 1917, aged 37, to recuperate after suffering a nervous breakdown while serving in the German army during the First World War. He was renowned as one of Europe’s most important modern artists, but his mind and body were broken. His life in Berlin had been hedonistic. He was hooked on absinthe and morphine. The war had been the final straw. Emotionally paralysed, he was in no fit state to fight.

The artist was fortunate. He knew a German doctor who was a big fan of his work, and this doctor wangled him a trip to Davos, widely regarded as Europe’s premier medicinal resort. The highest city in Europe, at an altitude of 1560m, its mountain air was believed to alleviate the effects of tuberculosis, so all sorts of clinics and sanatoria had sprung up here, not only for the treatment of TB, but all kinds of other ailments too. It is also where Thomas Mann set his novel, The Magic Mountain, and Robert Louis Stevenson wrote Treasure Island while staying in a sanatorium there.

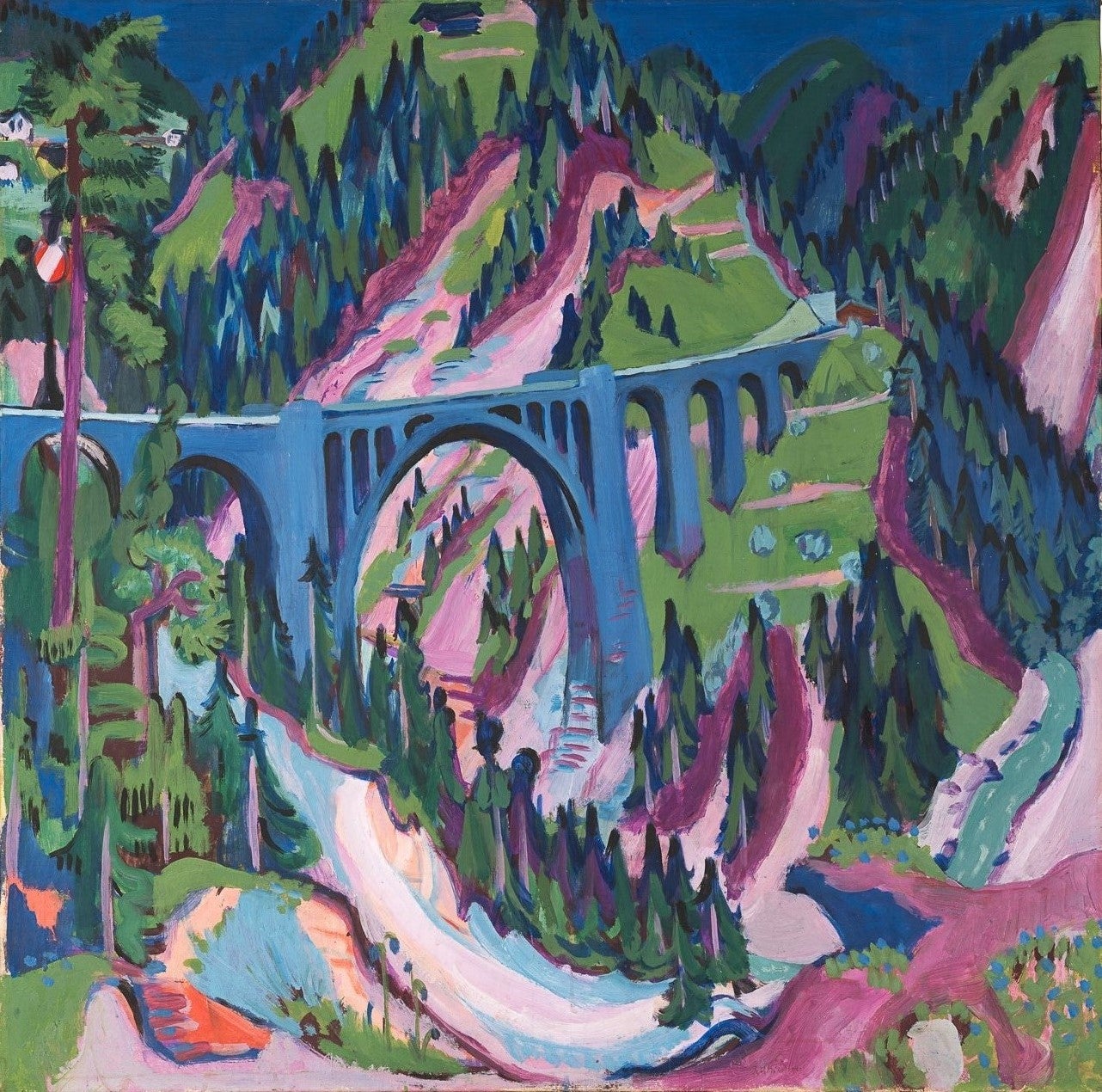

After his treatment finished, Kirchner stayed on in Davos but he had no interest in living in the city centre. Instead he rented a rudimentary wooden hut on the Stafelalp, a windswept hilltop over 300m above Davos. For a jaded urbanite like Kirchner, this rural lifestyle was a case of kill or cure. This austere outdoor life could have finished him off. Instead, it rejuvenated him. He tackled his addictions and returned to painting. But now, instead of dark, decadent studies of Berlin streetlife and nightlife, he began painting joyous pictures of the Alpine landscape all around him. “I wish to remain in the world,” he declared. “The high mountains will help me.” And they did.

Kirchner’s worries about the Nazis weren’t confined to Germany. There were also Nazis on his doorstep. Many Germans lived in Switzerland, a good many of them lived in Davos

After a few years on the Stafelalp, Kirchner relocated to a farmhouse called In den Lärchen, a few hundred metres below – a bit more comfy and a bit less isolated, but still fairly rudimentary nonetheless. After a few years here, he moved to another farmhouse about a mile away. It was in this farmhouse, called Wildboden, that he spent the last 15 years of his life.

Kirchner’s first 10 years in Wildboden, from 1923 to 1933, were among the happiest years of his life. Kirchner was now living with his lifelong muse, Erna Schilling, whom he’d known since his Berlin days – Erna and her sister Gerda were dancers in Berlin nightclubs. Gerda visited the couple in Davos. Another visitor was the dancer, Nina Hard. All three women feature in his paintings.

Davos was only a few miles away, yet Kirchner played little part in the social life of this lively resort. He liked to walk into town to drink a cup of coffee at Cafe Schneider (still there today) and read the newspapers, but he wasn’t interested in hobnobbing. His only real interest was his work. His feelings for Erna were sincere, but he declined to marry her, or give her children. He said he was incapable of loving anyone with sufficient intensity to become a husband or a father. His deepest emotions, he explained, were channelled into his art. “My work emerges from the yearning of loneliness,” he wrote. “The more I mingled with people, the more lonely I felt.”

Kirchner’s sense of separation was reflected in his painting. He painted a few pictures of Davos, but most of his paintings were of the mountains. “Fantastical colours stand before me,” he wrote. “I must work alongside nature.” If you’ve never been to Davos, Kirchner’s pink and purple hues may seem sentimental, implausible, but spend a few days in these mountains and you realise these “fantastical colours” are precisely what he saw.

For a man who’d made his name painting Berlin streetlife, this was a radical departure, but his new work was well received. Despite his relative isolation, he remained in contact with German art dealers, and he continued to sell well in Germany. After 10 years in Wildboden, his future looked secure. He was in his early 50s, at the peak of his artistic powers. And then Hitler came to power in Germany, and Kirchner’s life began to fall apart. At first he was in denial: “We’ve been hearing terrible rumours about the torture of the Jews, but it’s surely all untrue”. Yet even ensconced in neutral Switzerland, the bad news spewing out of Germany became impossible to ignore.

With the benefit of hindsight, Davos seems like a pretty good place for Kirchner to have sheltered from the Third Reich, but it didn’t seem like that at the time. Although he was only an occasional visitor to Germany, it remained the main market for his work, and as the Nazis set out to demonise modern art, his sales began to suffer.

And it wasn’t just about the money. Kirchner was a German patriot, and what was happening in Germany was deeply painful for him, even at a distance. “I am a German painter,” he said. “I was born in Germany, achieved fame and sold my work in Germany. I now thank the country by remaining German.” He never became a Swiss citizen, though it would have made his life a lot easier.

Kirchner’s worries about the Nazis weren’t confined to Germany. There were also Nazis on his doorstep. Many Germans lived in Switzerland, a good many of them lived in Davos, and in 1932 one of them, Wilhelm Gustloff, founded a Swiss branch of the Nazi party. The party HQ was in Davos and Gustloff was its leader. As an avant-garde artist with an eccentric lifestyle, living with an unmarried woman, Kirchner was an obvious bogeyman for this reactionary crusade. The exterior of his house was adorned with his expressionistic wooden sculptures. He now felt compelled to remove them and destroy them, so as not to attract attention.

In 1936, Gustloff was shot dead in his home in Davos by a Jewish student, David Frankfurter, as a protest against Nazi antisemitism. Frankfurter’s trial became a cause celebre, Gustloff’s coffin was transported by train from Davos back to Germany, amid immense pomp and ceremony, and Hitler attended Gustloff’s funeral. This incident left Kirchner feeling increasingly exposed. The Nazi movement in Davos was now centre stage.

Worse was to follow. In 1937, Kirchner was denounced as a “degenerate” artist by the Nazis, and forbidden to sell or display his work in Germany. Hundreds of his paintings were removed from public galleries. A selection of these confiscated artworks were exhibited in the notorious Nazi “degenerate art” exhibition, a crude display designed to ridicule and humiliate modernist artists like Kirchner. Many were then sold abroad. Some were destroyed. As Schilling confirmed, this caused Kirchner “tremendous emotional suffering.” A German patriot, he still regarded Germany as his Heimat, his Fatherland.

In 1938, Hitler’s Wehrmacht marched into Austria. Davos was only 15 miles from the Austrian border. Now the Third Reich was only a few hours’ march away. We know now that Hitler would never invade Switzerland. We know now that Switzerland would remain neutral, rather than forging an alliance with the Third Reich. But no one, least of all Kirchner, could have been sure of that. “Those who appreciated my paintings were Jews – my best and most decent art dealer was a Jew,” he wrote, in the spring of 1938. “They accepted my paintings.” A few months later, he shot himself, in the field outside his house. Schilling said, “he chose a radiantly beautiful day to end his life.”

Kirchner is buried in the local cemetery, a beautiful wooded glade barely a hundred yards from Wildboden. Schilling lived on in Wildboden, alone, until her death in 1945. She’s buried alongside him. Although they never married, the name on her headstone reads Erna Kirchner. It feels like a fitting tribute to a woman who had sacrificed so much to support his art.

The three houses where Kirchner lived are all still standing. They all look just the same, and so does the landscape that surrounds them. Standing outside them, you can recognise the scenes he painted. None of them are open to the public, but that doesn’t matter. It’s their settings which are significant, and a hike around them is a wonderful way to get inside his head.

I’ve done this trek three times now, and it gets better each time I do it. I like to do it in chronological order, following the course of Kirchner’s life. I start by hiking up to the Stafelalp, a bare hillside above the treeline. From here, you can look down on the other two houses that he lived in. On the way down you pass In den Lärchen, and from there it’s an easy walk to Wildboden, and finally on to Waldfriedhof, the bucolic cemetery next door.

“In the 20 years I’ve been here, I’ve always been treated with kindness,” wrote Kirchner, not long before he died. Standing here, beside his headstone, that kindness seems to extend beyond the grave. This graveyard feels supremely peaceful. The gravestones are hidden within a copse of enormous evergreens. Kirchner clearly liked it too. He made a rough sketch of it. You can see his house from here, through the trees. It seems strange that he’s buried so close to where he lived, so close to where he killed himself. But then there’s a lot about this tale that’s strange. It feels like a kind of fable, although what it signifies I couldn’t say.

I end up back at the Kirchner Museum in Davos. Intimate and emotive, these pictures never lose their resonance. Each time you stand in front of them, they seem more vibrant, more alive. I used to like his Berlin paintings best, but now I prefer these ones. They’re more hopeful, more optimistic. They make you want to carry on. And now, finally, foreign curators are starting to appreciate them, rather than simply focusing on his work before the First World War. Kirchner never stopped developing, and to discover his Swiss work is like discovering a new artist. “The art world is catching up,” says Beisiegel. “Kirchner reinvented himself in Davos.”

For more information about Kirchner in Davos, visit www.davos.ch, www.myswitzerland.com or www.kirchnermuseum.ch

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks