‘Very powerful and yet very simple’: Henry Moore in the Sixties

Two new exhibitions explore how the 20th-century sculptor stayed true to his own vision, as much in his art as in his personal life, writes William Cook

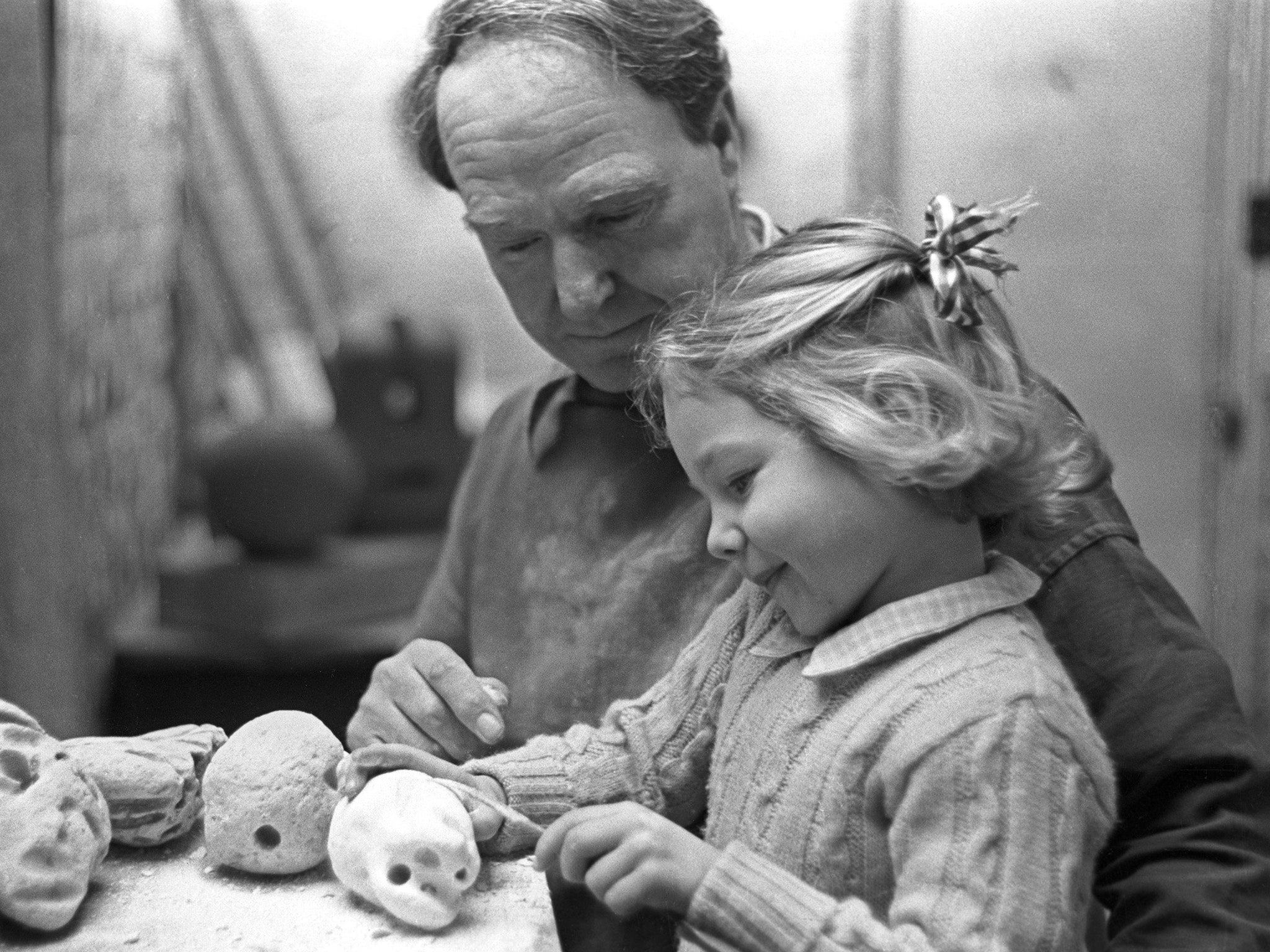

In the leafy grounds of Hoglands, an old farmhouse in rural Hertfordshire where Britain’s greatest sculptor, Henry Moore, lived and worked for nearly half a century, his only child, Mary Moore, is showing me some of her father’s greatest artworks. Mary grew up here, she played here as a child, and today these gardens are given over to his iconic sculptures.

“In a way, he saw the fields as open-air galleries,” says Mary. “The light changing, the weather changing, the time of day changing, from morning to night – all of those things change how a sculpture looks. It’s the most modern way, to my mind, of seeing sculpture in daylight, because you get a constant variation which changes your relationship to it.”

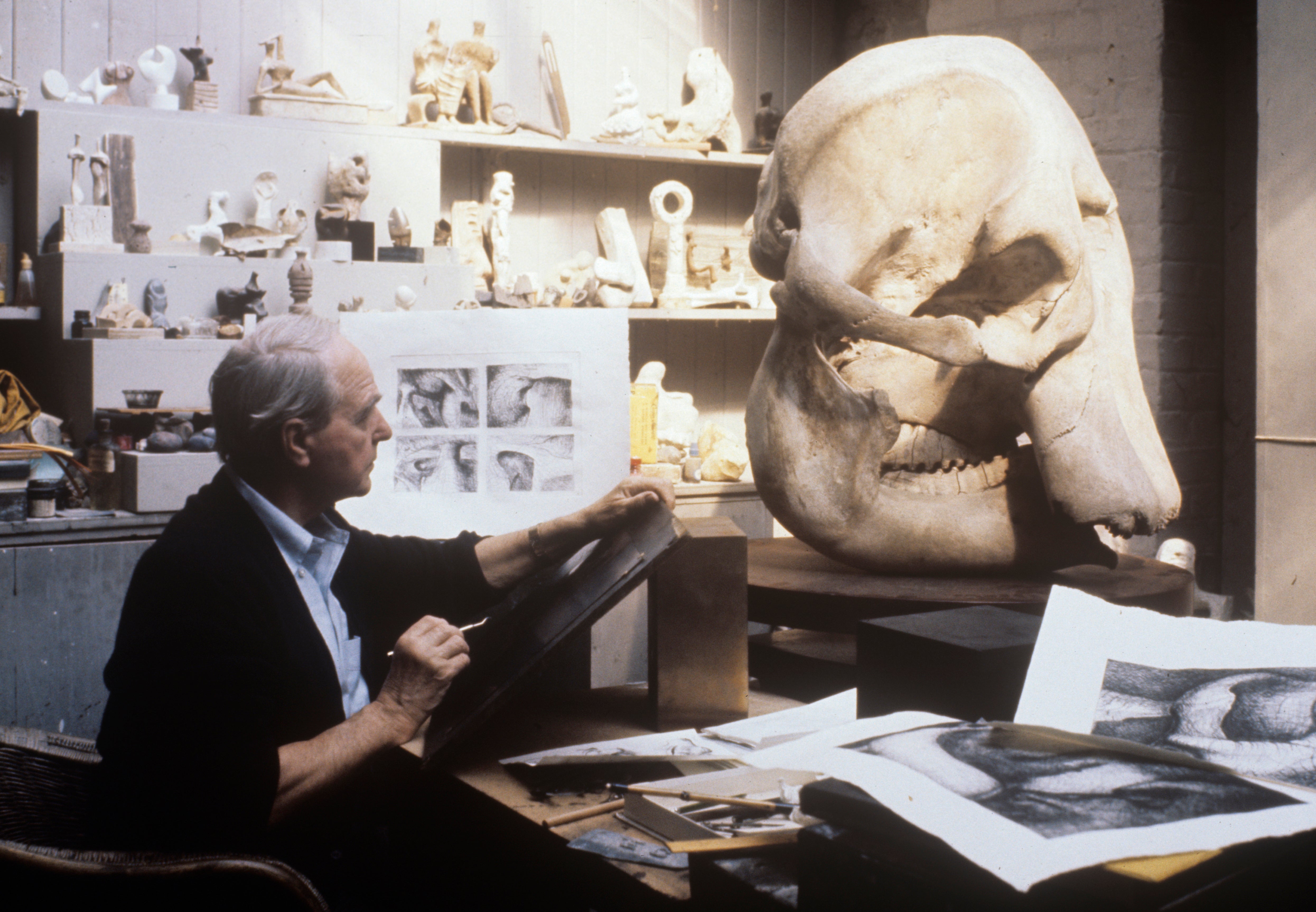

Moore loved to sculpt outdoors. “He worked outside, he liked to be outside,” says Mary. “He was utterly miserable if he couldn’t work.” Moore lived here from 1940 until his death in 1986, and his personality still looms large: in the little summerhouse where he used to sit and draw; in the airy studio where he made his maquettes; in the stables and the farmyard where he made his sculptures; in the homely farmhouse where he lived with his wife Irina, and their daughter Mary. Even after all these years, it feels as if he’s still around.

On my first visit here, 30 years ago, Moore’s sculptures seemed strange and futuristic, but seeing them again today I realise something’s shifted. Today they seem elemental, in tune with the natural landscape, closer to the antique relics in the British Museum which excited him as a student than the abstract artworks of the contemporary sculptors he’s inspired.

“He had three favourite subjects, really, which he returned to endlessly,” Mary tells me, as we sit and drink our tea together outside the house where she was raised. These subjects were the human head, the reclining figure and the mother and child, all eternal themes any prehistoric sculptor would have recognised. Despite the sneers and jeers of the traditionalists, he wasn’t remotely iconoclastic. On the contrary, his sculptures built bridges between the modern world and the lost worlds of our ancestors. “They show a kind of optimism, and a belief in the human spirit,” says Mary.

For the last 15 years Hoglands has been open to the public, providing an intimate insight into Moore’s private life. For one of the most famous artists of the 20th century, the house is remarkably modest, which is apt, for Moore was a no-nonsense Yorkshireman, renowned for his down-to-earth approach. His sculptures were profound, but his working methods were supremely practical. His home was part studio, part workshop.

We step inside the house, a cosy country cottage with low ceilings. “This is where he died,” says Mary, leading me into the sunlit sitting room. “This room had in it all the things he loved.” It’s full of books and sculptures, drawings and paintings, but there’s nothing lavish or ostentatious about it. It’s like the home of a country vet with a keen interest in art. I never met him, but in films and photographs he comes across as a calm and kindly man, someone comfortable in his own skin. “He knew absolutely who he was, and he was utterly clear about what he was doing,” says Mary.

Nowadays it’s hard to understand what the fuss was all about, but that’s because Moore changed the way we look at art, in Britain and beyond

I’ve come here today to see a new show called Henry Moore: The Sixties. Moore had been a leading light of the British art scene since the 1930s, but by the Sixties he’d become a worldwide star. Before then, no British artist had enjoyed a global reputation. Moore changed all that. By the time he died, at the grand old age of 88, his work was renowned all around the world. “It’s very powerful and yet very simple,” says Hannah Higham, the curator of this exhibition. So how did Moore become the most significant British artist of the 20th century, and why is his work still so resonant today?

He was born in 1898, the seventh of eight children, in a tiny terraced house in Castleford, a Yorkshire mining town. His father was a miner with a passion for education. Henry was studious, but above all he yearned to be a sculptor. He won a place at the local grammar school where he met an inspiring teacher, Alice Gostick, who nurtured his innate love of art.

When Henry left school his father told him to learn a trade, so he trained to be a teacher. Then came the First World War. Henry joined up and was sent to the Western Front. He was gassed at the Battle of Cambrai and sent back to Blighty (later, he recalled “the insufferable agony and the depravity” of war). After the horror of the trenches, sculpture seemed a lot less risky. Teaching could wait. He won a scholarship to the Leeds School of Art, and subsequently another scholarship, to the Royal College of Art in London.

Sculpture was barely taught in British art schools back then (Moore was the only sculpture student in his year, in Leeds and then in London) but he was talented and resolute, and by the time he graduated his work was already making waves. He was receptive to modern movements like Cubism, but he was equally in tune with classical and tribal sculpture. The result was a style which was progressive, yet also rooted in the distant past. His sculptures were intensely personal, the result of a passionate engagement with each block of wood or stone. “Every inch of the surface is won at the point of the chisel,” he explained. “Every stroke of the hammer is a physical and mental effort.”

Right from the start, Moore was admired by other artists (he met Picasso in Paris; his work was bought by Jacob Epstein), but it took the British art establishment a long time to catch up. His work was mocked in the popular press and castigated by art critics. “Moore shows an utter contempt for the natural beauty of women and children,” ranted The Morning Post, beneath the inflammatory headline, “Cult of Ugliness Triumphant”.

Nowadays it’s hard to understand what the fuss was all about, but that’s because Moore changed the way we look at art, in Britain and beyond. Before Moore came along, any artist who deviated from naturalism ran the risk of being derided as talentless and subversive, even fraudulent. More than any other artist, Henry Moore opened British eyes to modern art.

It's easy to forget what a radical figure he was at the time. When the Nazis declared war on modern art, removing modernist works from public galleries, Moore was the only British name on their list of “degenerate” artists. If Hitler had invaded Britain, he would have been a marked man.

Yet Moore was never a noisy advocate of modernism. He didn’t court controversy. He preferred to keep his head down, and focus on the job in hand. “I’ve never worried much about the communication between the artist and the general public,” he reflected in later life, in the BBC’s Face to Face, with John Freeman. “I believe that, given an opportunity, the average person will learn to appreciate sculpture or painting if he’s only given the chance.”

That opportunity arrived during the Second World War. Moore was too old to fight (he was now in his early forties), but he was living in London and the Blitz brought the war to his front door. He started sketching his fellow civilians, sheltering from the Luftwaffe in the Underground stations. These evocative drawings encapsulated the quiet heroism of ordinary Londoners, and they captured the imagination of the British public. People realised that modern art had something to say about their lives, and that modern artists like Moore were patriots, not anarchists or revolutionaries.

The Blitz also prompted Moore’s exodus to Hertfordshire. In 1940, his London home was damaged in a bombing raid. Thankfully, Henry and Irina weren’t there at the time – they were staying with friends in Much Hadham, a village in Hertfordshire – but now their house was uninhabitable, so their friends suggested they stay on in Hertfordshire for a while. They found rooms to rent at Hoglands, a farmhouse in Perry Green, near Much Hadham. At first, they rented half the house, then the whole house, and then they bought it. It was here that his greatest sculptures were conceived and made.

After the Second World War, Moore’s career reached another level. He’d been highly regarded before the war, but only among the cognoscenti. Now he became a household name. In 1946 (the year Mary was born), he made his first visit to the US, for a retrospective of his work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In 1951, London’s Tate Gallery followed suit.

Moore’s monumental artworks would have graced any era, but after the Second World War he was the right man in the right place at the right time. Architects were building for the future, in stainless steel and concrete. Moore’s timeless sculptures gave these brave new cityscapes the human touch.

Honesty, compassion, integrity – these are the words that people reach for when they describe him, as an artist, and as a man

But Moore far preferred to site his sculptures in the countryside. Today this is common practice, but it was something he pioneered. He’d always been intrigued by archaic sites like Stonehenge. By placing his artworks in the great outdoors, at the mercy of the elements, he took sculpture back to its ancient origins. He understood the relationship between landscape and the human form.

In 1977 Peter Murray founded Yorkshire Sculpture Park, in the grounds of an old stately home in a wooded valley between Wakefield and Barnsley, and he asked Moore to lend him some sculptures for this fledgling site. Moore was nearly 80, inundated with offers from all sorts of international institutions, but he was happy to help out. Moore’s participation, so early on, was crucial in attracting other sculptors to this innovative venture. Forty-five years later, Moore’s sculptures still have pride of place at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and it’s now Britain’s leading venue for outdoor sculpture.

“Moore always felt there should be a sculpture park in this country,” Murray tells me. “By then he’d more or less decided that the open air, the landscape, was the best place for his work.” Moore offered Murray financial support, as well as sculptures. He visited Yorkshire Sculpture Park and was thrilled by what he saw. “He liked the idea of being able to approach sculpture from a distance, the way it changed as you approached it.”

For Moore, visiting Yorkshire Sculpture Park was like a kind of homecoming. His life had come full circle, the miner’s son from Castleford who dreamt of being a sculptor, who went away to London, and returned to Yorkshire 60 years later, to return his sculptures to the landscape that had shaped him. “He liked to talk a lot about his background,” says Murray. “Castleford, Yorkshire, coalmining… his roots were extremely important.”

In 1987, a year after Moore died, Murray mounted a memorial exhibition of Moore’s work at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. It was a great success. The only sadness was that Moore wasn’t there to see it. “He was trying to do something which was obviously very different, but which at the same time respected the roots and the history of sculpture - it went right back to the beginning,” says Murray. “He attracted huge hostility. He was called a corrupter of youth. He was called a Bolshevik. He was criticised by the president of the Royal Academy. His students at the Royal College of Art signed a petition to get rid of him.” But Moore wasn’t bothered. He was confident in his abilities, sure of what he wanted to do, and he produced an enormous array of sculptures, of unending strength and subtlety. He bridged the gap between figuration and abstraction – he articulated how it feels to be alive. As Murray says, “The deeper you dig, the more powerful his work becomes.“

I travelled to Yorkshire Sculpture Park to take another look at Moore’s sculptures, and to meet up with Godfrey Worsdale, the director of the Henry Moore Foundation. “The Yorkshire landscape always resonated with Moore,” Godfrey tells me. It’s fitting to find so many of his sculptures here, on a windswept hillside, a few miles from the mining town where he came of age. Moore never lost the values that were instilled in him in Castleford – above all, the value of hard work, self-improvement and plain speaking. “He was incredibly pragmatic, incredibly clear in his direction, in his mission,” says Godfrey. “There’s never any prevarication with Moore.”

A short drive away, in Leeds, where Moore first studied sculpture, is the Henry Moore Institute, a unique sculpture gallery, library and study centre established by Henry Moore. “He thought very carefully about his legacy – he wanted to give back,” says Laurence Sillars, head of the Henry Moore Institute. “It has his name above the door, it has his benevolence at its heart.” It's there for anyone who’s interested in sculpture. Whether you want to make sculpture, study it or just look at it, you’ll be welcome here.

Moore was true to his own vision, and he pursued it with complete commitment. He wasn’t distracted by his fame, or the wealth that came with it. He never acted like a superstar. Honesty, compassion, integrity – these are the words that people reach for when they describe him, as an artist, and as a man. These qualities informed his art, and his relationships: his happy marriage, his happy family life, his tireless support for other artists. And because he was a good person, he saw beauty and goodness all around him. “There is an infinite amount to be seen and enjoyed in the world,” he declared, towards the end of his long life. “The texture of bark on trees, the shape of a shell... to observe, to understand, to experience the vast variety of space, shape and form in the world, 20 lifetimes would not be enough.”

Henry Moore: The Sixties is at the Henry Moore Studios and Gardens, Hertfordshire from 1 April to 30 October. Henry Moore: Sharing Form is at Hauser and Wirth, Somerset from 28 May to 4 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks