Louise Bourgeois: How a great sculptor finally found fame

The spider sculptor started her art early but it wasn’t until the 1980s through to the 2000s that her work was able to blossom, and now she is getting the recognition she deserves, writes William Cook

I can still recall the first time I saw Louise Bourgeois’s enormous spider at London’s Tate Modern, 22 years ago. It was one of those rare moments when a new artwork becomes an instant icon, something timeless and universal, like Monet’s waterlilies or Van Gogh’s sunflowers. I’d never seen anything quite like it. It was sinister yet seductive, frightening yet alluring, not so much like modern art – more like a monster from another world.

The next time I saw Bourgeois’s spider was outside the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. I saw it again a few years later, at the National Convention Centre in Qatar. It seemed to be following me around the globe, like some spooky apparition. Each time I saw it, it felt more potent than before.

Back in 2000, when I first saw that disturbing sculpture, I knew nothing about the woman who made it. It seems I was not alone. Bourgeois had been a familiar figure on the New York art scene for half a century, but in the wider world she remained relatively unknown. It wasn’t until 1982, when she was granted a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, that her work began to receive recognition beyond the cognoscenti.

Bourgeois was already 70 when that retrospective opened at the Museum of Modern Art. At the time it seemed like a swan song, a belated tribute at the end of a long, unsung career. Yet, this tiny, feisty woman had almost 30 years left in her. Seventy is the sort of age when most artists start slowing down, yet Bourgeois achieved more in her 70s, 80s and 90s than most artists manage in their 20s, 30s and 40s. The work she did from the 1980s through to the 2000s was some of the best she ever did. When she died, in 2010, at the grand old age of 98, she’d finally become a household name.

A dozen years since her death, the art world is finally catching up with her. Over the next few months, she’s the subject of three major exhibitions, at the Hayward Gallery in London, at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (there will also be an exhibition of her work at Hauser & Wirth in Somerset in the autumn).

Bourgeois was born before the First World War, yet her art has never seemed more topical. “She was ahead of her time,” says Ralph Rugoff, the director of the Hayward Gallery and the curator of the Hayward’s Bourgeois show. And she was utterly unique.

“She never lost her identity,” concurs Anita Haldemann, co-curator of the Kunstmuseum show. “She never catered to any fashion.” So who was this extraordinary woman, who lived so long and blossomed so late? And why are her enigmatic artworks so resonant today?

“I was completely starstruck,” says Iwan Wirth, President of Hauser & Wirth, one of the world’s leading commercial galleries, recalling his first meeting with Bourgeois, in her twilit townhouse in Manhattan. “She broke so many rules.” She was the first artist to join Wirth’s gallery, which he co-founded with his wife, Manuela Hauser. Wirth has met a lot of famous artists, but you can see why he was blown away. She was eloquent, outspoken and intensely charismatic. She’d hobnobbed with all sorts of artists, from Marcel Duchamp to Andy Warhol. She’d known Bonnard, Vuillard, Miro, Matisse and Giacometti. Her life was like a time machine, back to the heyday of modern art.

She was not an easy woman to live with. Even her friends and fans were wary of her explosive temper. Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern, found her “extremely intimidating.” Another of her admirers, Anthony Gormley, likened her – affectionately – to a witch from a Grimm’s fairytale, “filled with extraordinary electric venom.” However there was something tender and vulnerable about her too – something fragile, innocent, almost childlike. “I’ve failed as a wife, as a woman, as a mother, as a hostess, as an artist, as a businesswoman, as a friend, as a daughter, as a sister,” she wrote, towards the end of her long life. “I have not failed as a truth-seeker.” She told the truth about herself, and her own experiences, however intimate, however painful – and in so doing, she changed the way we look at art.

While her father held court at the dinner table, she made little men out of the bread upon her side plate, little models of her father. Then she pulled off their arms and legs

Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911, the second of three children – a disappointment to her father, who wanted a son. Her parents ran a small family firm which restored antique tapestries. Ostensibly it was a team effort, but her mother did most of the work. Her mother was dutiful and diligent; her father was a philanderer. The firm did well enough for them to afford a live-in governess, a young Englishwoman with whom Louise’s father began a long and lusty affair, under the noses of Louise and her mother. This betrayal cast a long shadow over Louise’s childhood, and her later life.

Such behaviour, though reprehensible, was hardly unusual in the 1920s, but while a lot of people might have shrugged it off, its effect on Bourgeois was overwhelming. She felt betrayed by her father, whom she’d idolised; she felt betrayed by her governess, whom she’d adored; she felt fiercely protective of her mother but was unable to help her. At mealtimes her father talked and talked while the women sat in silence. Her mother diffused the tension by smashing crockery. It sounds like a scene from an Ibsen play.

Louise’s protests were more discreet. While her father held court at the dinner table, she made little men out of the bread upon her side plate, little models of her father. Then she pulled off their arms and legs. These makeshift voodoo dolls were her first sculptures. From the start, her art was introspective and therapeutic, exposing secrets which no-one else dared to reveal. Powerless, like so many children, unable to control or change her circumstances, she learnt to channel and dispel her anxiety through her art. “In order to liberate myself from the past I have to reconstruct it, ponder it, make a statue out of it, and get rid of it,” she said. “Through making sculpture, I’m able to forget it afterwards. I’ve paid my debt to the past and I’m liberated.”

Louise’s mother taught her the rudiments of tapestry restoration, and she soon became a skilful seamstress. One of her tasks was replacing genitalia with flowers to appease prudish clients – Freud would have had a field day. Later, a lot later, these skills resurfaced in her art, but meantime she found comfort in the cool precision of mathematics. As she said: “I got peace of mind only through the study of rules nobody could change.” She went to the Sorbonne to read maths but then in 1932, when she was 20, her mother died. She’d been ill for a long time, having never entirely recovered from a bout of Spanish Flu. Grief-stricken, Louise switched to art.

She graduated from the Sorbonne in 1935 and did further training at the Louvre. She studied under the Cubist artist Ferdinand Leger, who told her she was a sculptor, not a painter. In 1938, she opened her own gallery in Paris, where she met the American art historian Robert Goldwater. He was a complete contrast to her father. “They were like fire and water,” she said – her father was the fiery one while Goldwater was like water. They fell in love and married and went to live together in New York. The timing was fortuitous. In 1939, France went to war with Germany; in 1940, Paris was occupied by the Nazis. Bourgeois and Goldwater raised a family in New York. She became an American citizen and she spent the rest of her life in New York.

The 1940s and 1950s was the first flowering of Bourgeois’s idiosyncratic talent. She befriended abstract expressionists like Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, but while these artists became superstars, she remained obscure. Her work was so eccentric, and her range of genres so eclectic – painting, sculpture, tapestry, collage, printmaking, even poetry – that you’d struggle to find a place for her in a conventional survey of 20th century art. In a way, this was a blessing. Her art was entirely separate, outside any school or movement, and although the public indifference was hard for her to bear, it made her more original. Overlooked yet undeterred, she found her own way through.

“She was definitely someone who other artists have always rated very highly,” says Ralph Rugoff, “but it may have been that her work was too singular to get the kind of market success back then which leads to celebrity in the art world.” This singularity went way beyond the cultivation of a certain style. “She experienced things incredibly intensely,” says Rugoff. “In her sculpture she’s able to convey that, so that somebody looking at it has a very visceral feeling.” As he says, her sculptures express what things feel like from the inside rather than what they look like from the outside. “She never covers anything up,” agrees Haldemann. “She puts it all out there in a very honest and open way.”

She regarded these spiders as protectors, spinning webs to feed their families. Yet for the rest of us, the spider is a fearsome predator

“I’m a prisoner of my memories,” said Bourgeois, “and my aim is to get rid of them.” Yet she never entirely exorcised those demons, however hard she tried. “She was somebody with a lot of psychic stress,” says Rugoff, but that stress was what fuelled her art.

For Bourgeois, art was a form of psychoanalysis. She wasn’t engaged in a dialogue with the outside world, but with her inner psyche. Nowadays such an approach is a lot more commonplace, but back then it was something new. “The artist has the privilege of being in touch with his or her subconscious,” she argued. “No exhibition is important. The progression in the work is important. Self-knowledge is its own reward. A show is just a show.”

That introversion was one reason for her neglect. Another was her gender. Back then, the art establishment was far more chauvinistic than it is today. Most critics and curators were men, art was regarded as a male pursuit, and female artists were generally patronised or ignored. Bourgeois always resisted being pigeonholed as a “female” or “feminist” artist, but she couldn’t change the prejudices and preconceptions of society at large. “For some people, at that time, any excuse was a good excuse not to show women’s art,” says Wirth.

For any married woman in 1950s America, pursuing any kind of career was a direct challenge to the status quo – and despite its bohemian image, the art world wasn’t all that different. It seems her marriage to Goldwater was fairly happy (he died in 1973, when Bourgeois was 61, after 35 years together), but raising their three sons while he held down a steady job, her own artistic aspirations were bound to play second fiddle. She tackled these inequalities in her art – the ambivalence of motherhood; the frustrations and constrictions of home and family – but an art world dominated by men was bound to be less receptive to such concerns. It’s no coincidence that she began to gain acceptance when women began to acquire more power.

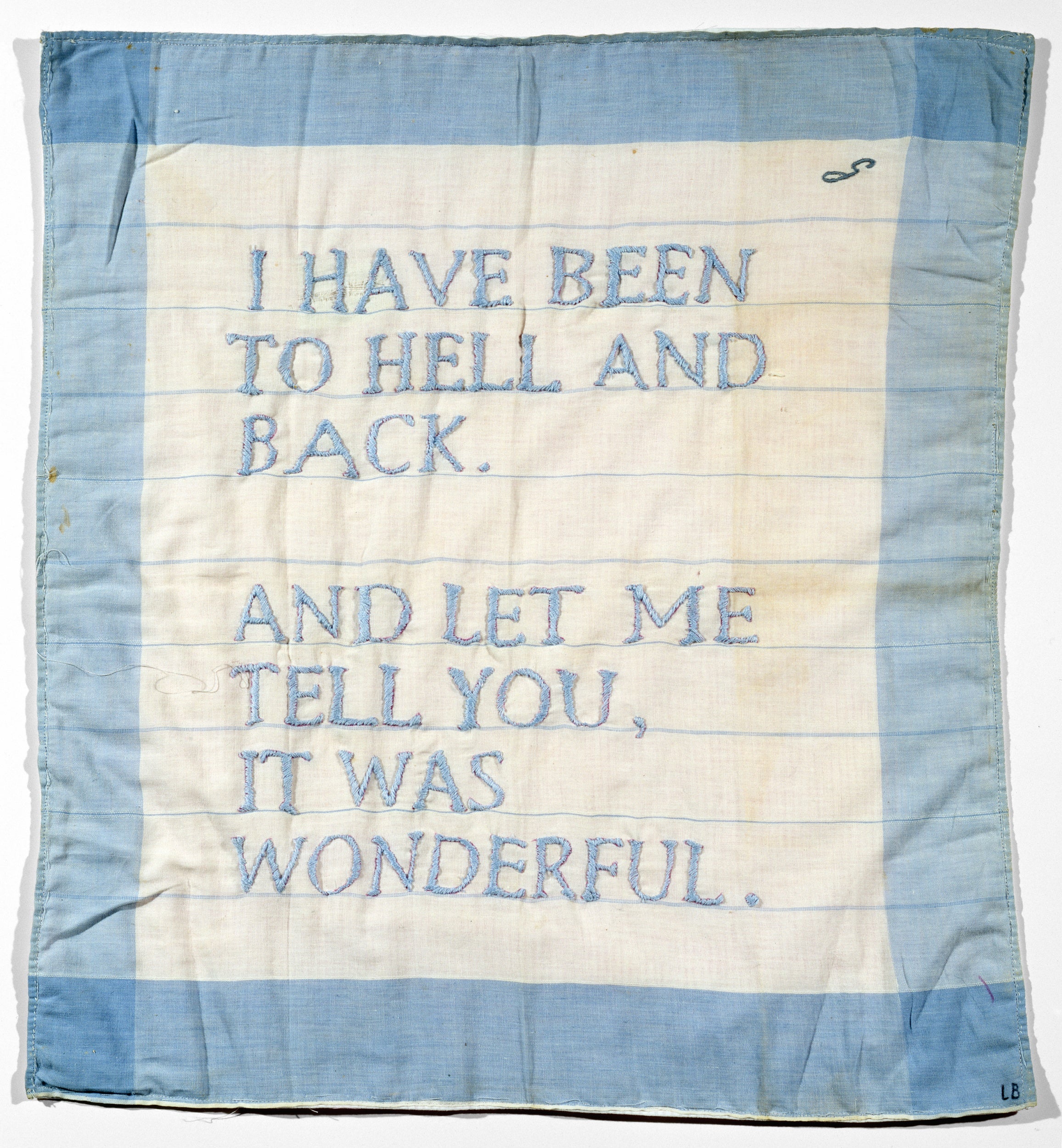

For Bourgeois that tipping point came at the start of the 1980s, and over the next 30 years she made up for lost time. Her longevity gave her a second chance which was denied to so many women. She exhibited all around the world and acquired a new generation of admirers and collaborators, such as Tracey Emin, who was young enough to be her granddaughter. As Emin told the BBC, describing what she loved about Bourgeois’s art: “she put her heart and her soul into it.”

It’s that uncompromising approach which makes her work seem so contemporary. As Wirth says, her work hits you in the stomach – it moves you to the core. “I have goosebumps when I see the work. I respond to it physically. That’s what great art does to me – only the greatest do that.” When Wirth started selling Bourgeois’s work, in the 1990s, all his collectors were women. Not anymore. “She speaks more and more to a new generation, of every age, every gender, anywhere in the world.”

During the last years of her life, Bourgeois rarely left the narrow brownstone in Chelsea, NYC, where she’d lived since 1958. Instead, the world came to her. Up and coming artists would come and visit her, and show her their work, and brave her ruthless judgements. She didn’t spare their feelings. Her passionate engagement was proof enough of how much she cared. “It is not a torment to be an artist,” she admonished a young artist, in one of these encounters. “It is a privilege.” For her, the torment wasn’t in her art, but in her life.

The final resolution of that torment, it seems, came in her sculptures of spiders – various versions, executed in the autumn of her life. “The spider is an ode to my mother – she was my best friend,” she explained. “Like a spider, my mother was a weaver.” She regarded these spiders as protectors, spinning webs to feed their families. Yet for the rest of us, the spider is a fearsome predator, which ensnares and devours its prey. The reason her spider is such a powerful symbol is because, like all her best work, it’s so ambiguous. Bourgeois always maintained that it was a representation of her mother, but the more I look at it, the more I see it as a representation of herself.

Louise Bourgeois – The Woven Child is at the Hayward Gallery, London (www.southbankcentre.co.uk) from 9 February to 15 May; Louise Bourgeois & Jenny Holzer – The Violence of Handwriting Across a Page is at the Kunstmuseum, Basel (www.kunstmuseumbasel.ch) from 19 February to 15 May 2022; Louise Bourgeois – Paintings is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (www.metmuseum.org) from 12 April to 7 August 2022

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks