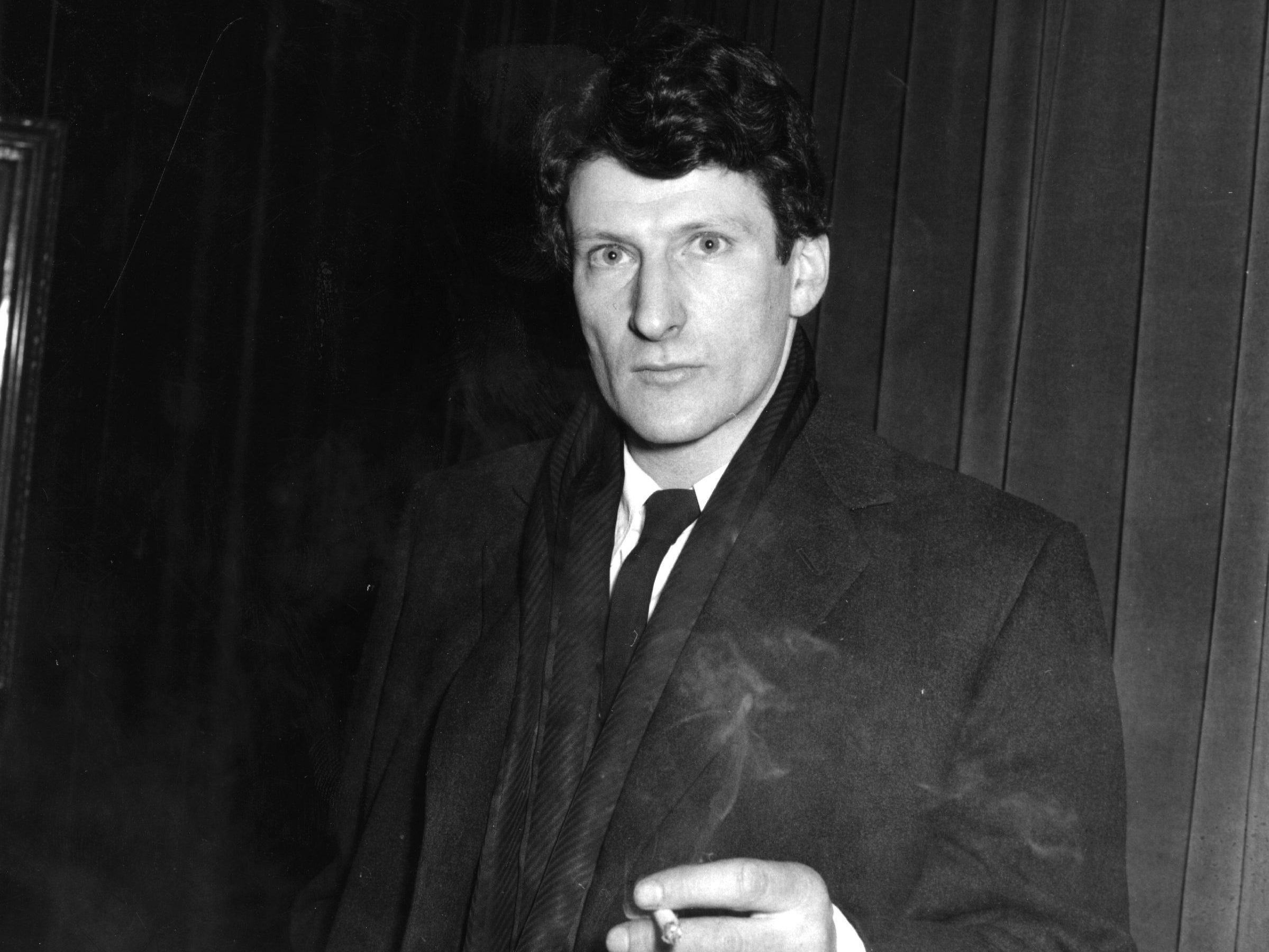

‘To astonish, disturb, seduce, convince’: Lucian Freud, warts and all

It’s 100 years since Britain’s greatest portrait painter was born. William Cook looks at what made the controversial painter who he was

In a sunlit drawing room at Chatsworth, one of Britain’s grandest stately homes, the 12th Duke of Devonshire, “Stoker” Cavendish, tells me about his family’s close friendship with Britain’s greatest portrait painter, Lucian Freud. Freud was a friend of Stoker’s father, the 11th Duke. He was a frequent guest at Chatsworth. Over the course of 20 years, he painted six members of the Cavendish family, including the man I’ve come to see today.

The Duke of Devonshire was 18 when he sat for Freud, in his London studio. “He was the best company,” recalls Stoker. “He didn’t talk down to you at all. He just made everything great fun.” Freud’s erratic lifestyle was a world away from the Duke’s comfortable upbringing. “We had to wait until the electric meter man went, having been knocking on the door for half an hour, because the meter wasn’t paid. I wasn’t used to that sort of life at all, and it was thrilling. Lucian was completely unabashed by it. He probably had enough money, but he had a horse to back in the afternoon, so he couldn’t possibly give it to the electric meter man.”

Sixty years on, to mark Lucian Freud’s centenary, the Duke of Devonshire is mounting an exhibition of Freud’s paintings, drawn from his collection here at Chatsworth. The highlight of this absorbing show is Freud’s penetrating portrait of Stoker’s mother, Deborah, the youngest of the Mitford sisters. The Duke has called it “probably the most beautiful thing at Chatsworth.” For a man whose art collection includes several Rembrandts, that’s quite a compliment.

“My parents were thrilled with it,” Stoker tells me. “Their friends were completely disgusted and horrified.” Today it’s hard to see why they were so upset, but that’s because Freud changed the way we think about portraiture. Deborah Cavendish, nee Mitford, was attractive, intelligent and affluent, yet she’d had her share of heartache as three of her children died at birth. Freud captured her beauty, but he also portrayed her hidden grief. Here was a portrait artist who could see beyond the surface, revealing the personality within.

Stoker’s father was good friends with Freud. “They liked gambling, they liked racing – they had a lot of racing friends in common,” says Stoker. “He came here when we moved in. In fact, his name is the first name in our visitors’ book.” But when Freud painted Stoker’s father, he didn’t pull his punches. The 11th Duke of Devonshire slumps in his chair, head bowed, his collar and tie askance. “It was painted when my father was at a very low ebb – he was still an alcoholic,” reveals Stoker. “He stopped drinking for the last 20 years of his life, but when that painting was made, in 1971, he was in a really bad place, and I think that really shows.”

It isn’t the sort of portrait you’d expect to see of a wealthy, well-connected aristocrat, but Freud was no respecter of reputations. He hobnobbed with toffs and gangsters. He treated everyone the same. He painted what he saw, but there was more to it than that. His pictures exposes something unexpected about the sitter – something you never saw before. As the Duke of Devonshire says, “He really genuinely didn’t care what other people thought.”

Lucian Freud was born in Berlin 100 years ago, on 8 December 1922, the second of three children (his elder brother, Stephen, led a life of blameless obscurity; his younger brother, Clement, became a media star and a Liberal MP). His father, Ernst, was a successful architect (and a frustrated artist). His grandfather was the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud.

Lucian enjoyed a happy, comfortable childhood in Berlin. Like most German-Jewish families, the Freuds were essentially secular, and fully integrated into German society. A lot of German-Jewish families thought Hitler’s anti-Semitic rants didn’t apply to them, and left it too late to emigrate, but Ernst had no illusions. In 1933, a few months after the Nazis came to power, he brought his family to London. Lucian was 10 years old. He never lost his German accent, but in virtually every other respect he left his German life behind.

Lucian was sent away to boarding school, first to Dartington Hall, and then to Bryanston. He was a talented, unruly student, with a precocious flair for art. He left school at 16 to train as an artist – first at the Central School of Art, and then at the East Anglian School of Painting & Drawing, a quirky institution run by the artist Cedric Morris.

During the Second World War he joined the Merchant Navy and sailed in an Atlantic convoy, but was invalided out with TB. He found a flat in Paddington – a much rougher part of London back then than it is today – and devoted himself to painting. He remained a painter, and a Londoner, for the rest of his productive, eccentric life. “What do I ask of a painting?” he once wrote. “I ask it to astonish, disturb, seduce, convince.” It might have been a manifesto for his idiosyncratic art.

Freud had some early success, but for a long time he was better known by the cognoscenti than by the general public. He could be very prickly, but he was also good company – amusing, outspoken and sexually attractive. His social contacts were diverse, from penniless artists to wealthy aristocrats. He was a fearless gambler who often lost far more than he could afford. Several times, he had to ask his aristocratic friends for money to pay off loans to crooks who’d threatened him with violence.

Even as an old man, when his paintings were selling for huge sums, he still lived the bohemian life of the archetypal artist – careless of convention, flitting between high life and low life

In 1948 Freud married Kitty Garman, whom he’d met at art school. They divorced in 1952. In 1953 he married Lady Caroline Blackwood (he’d always been well connected with the upper classes) but this marriage also ended after just four years. Incapable of monogamy, he had relationships with numerous women thereafter – some long-term, some fleeting, some overlapping. In addition to his two daughters borne by his first wife, Garman, he fathered at least a dozen children out of wedlock (he once described himself, rather heartlessly, as “one of the greatest absentee fathers of the age”).

Even as an old man, when his paintings were selling for huge sums, he still lived the bohemian life of the archetypal artist – careless of convention, flitting between high life and low life, painting furiously in his spartan studio, subjugating everything else to the thing that mattered most to him, his art.

Freud argued that there was nothing erotic about painting portraits, and he was right, but his finished pictures still had a potent sexual charge. The art historian John Richardson said he turned sex into art and art into sex. Indeed it’s impossible to separate his virility, and his promiscuity, from his painting. These are not the paintings of a happily married man, living in suburbia, with the proverbial wife and two children. “A painter must think of everything he sees as being there entirely for his own use and pleasure,” he wrote. In his life, as in his art, people came second and art came first.

Some of Freud’s earliest paintings were surreal, but he soon honed in on portraiture, and it’s for his portraits that he’ll be remembered. “If you’re painting humans,” he reflected, “you’ve got the best subject matter in the world.” In the 1940s and 1950s, these portraits were incredibly precise – his portraits of his two wives are among the masterpieces of this period – but by the 1960s he’d switched abruptly to a more expressionistic style. He swapped his fine sable paintbrushes for coarse hog’s hair brushes, and his work became even more penetrating, more alive.

These paintings were uncompromising, often depicting his sitters in the nude, in awkward and unflattering postures, yet although his gaze was merciless it wasn’t gratuitously cruel. Freud cared about his subjects (“I paint only the people who are close to me”) and he would abandon a painting if he felt that connection wasn’t there. Many of his best portraits are of friends and lovers. Yet there’s also something dispassionate about his art, a sense of separation from the subject. It was this tension between separation and involvement that made his paintings so disturbing and alluring.

His nude portraits of the performance artist Leigh Bowery and benefits supervisor Sue Tilley were particularly shocking, on account of his ruthless depiction of their corpulence. Yet that sense of shock was our problem, not his. We’re accustomed to portrait painters who show the sitter in their best light, rather than scrutinising what’s really there. Freud was never willing to submit to this quaint convention.

Bowery and Tilley weren’t so unusual – you see plenty of people who look a lot like them every day. What was unusual was that Freud chose to paint them, in the nude, rather than more conventionally attractive models, and that he painted them warts and all, rather than airbrushing away their natural blemishes. “The naked body is somehow more permanent, more factual,” he declared.

Graham Greene said there was a splinter of ice in the heart of every great writer. Freud had that splinter in his heart, and this coolness and detachment was part of what made him a great portrait painter. “He was malign and magical,” Lucinda Lambton told the journalist and author Geordie Greig, in his intimate, illuminating portrait of the artist, Breakfast With Lucian. “I adored him but he was also very cruel.”

Lambton declined Freud’s invitation to let him paint her in the nude, but although he strips his sitters bare, this exposure often makes us view them with more sympathy. Andrew Parker Bowles sat for Freud in his full dress uniform as a Brigadier in the Household Cavalry, yet his pose was casual and informal – sat cross-legged in a battered old armchair, a pensive expression on his face, his belly spilling out from his unbuttoned tunic. The contrast between the uniform and the man within it is incredibly affecting.

Freud didn’t hold back, even with his own mother. He painted her in her old age, a period when she suffered from depression and mental decline. Freud was unsparing in depicting what was in front of him, and the results were disconcerting, but there was nothing exploitative about it. To my mind, there’s a quiet dignity about these portraits. And anyway, why should old age and all its associated woes be hushed up or sanitised?

Recognition, when it came, was welcome, as was the money that went with it – despite his austere working practices, he was partial to smart restaurants and smart clothes

This intense engagement was reflected in Freud’s working methods. “My object in painting pictures is to try and move the senses by giving an intensification of reality,” he wrote, in an article for Encounter magazine in 1954. “Whether this can be delivered depends on how intensely the painter understands and feels for the person or object of his choice.”

To sit for Freud was an exhaustive, exhausting process, an open-ended commitment which usually spanned many months and hundreds of hours. The art critic Martin Gayford describes this ordeal in engrossing detail in Man with a Blue Scarf, his fascinating book about sitting for Freud. For anyone prepared to go the distance, it was a stimulating and rewarding experience. “In a way, I don’t want the picture to come from me,” Freud told Gayford. “I want it to come from them.”

However Freud gave short shrift to any sitter who didn’t meet his exacting standards. In 1998, he embarked on a painting featuring Jerry Hall suckling her baby but when he became dissatisfied with her attendance rate, his solution was to replace Hall with a nude portrait of his assistant, David Dawson, still suckling Hall’s child.

The amount of time Freud spent on each portrait might seem obsessive but the results speak for themselves. Tellingly, one of the few sitters who sat for Freud who wasn’t able to give him the same sort of time was Her Majesty the Queen. Freud’s painting was far more interesting than most royal portraits, but it didn’t have the depth or insight of his more intensive work.

By the end of his life, Freud’s portraits were selling for seven, even eight figure sums, but for many years his sales were a lot more modest. At the age of 50, the most he could command for a painting was around a thousand pounds. Abstract Expressionism was the big thing in the 50s, Pop Art was the big thing in the 60s, and in the 70s Conceptualism was all the rage. Freud didn’t fit into any of these movements. His art ran counter to them. He stuck to his own path, oblivious to the fads and fashions of the art world.

It’s easy to forget what an outlier he once was. His approach to portraiture was radical, but fundamentally he was a traditionalist, committed to depicting the world he saw, as accurately as he could. In this respect he had more in common with the artists of the late 19th century than the artists of the late 20th century. It’s no coincidence that many of his favourite artists were Old Masters. “They have what every good picture has to have, which is a bit of poison,” he said of Titian’s paintings. He might have been talking about his own.

Freud was nearly 80 when he got his first show at the Tate, in 2002 (before then, his only non-commercial show was at the Hayward Gallery, in 1974). A weaker man might have been discouraged by these decades of indifference but Freud remained undeterred. “I’m egotistical,” he told Gayford, “but I’m not in the least introspective.”

Recognition, when it came, was welcome, as was the money that went with it – despite his austere working practices, he was partial to smart restaurants and smart clothes. But neither neglect nor fame affected his painting in the slightest. “I’m fairly immune to praise and abuse,” he said, in a phrase that recalls Kipling’s advice about triumph and disaster (to “treat those two imposters just the same”).

After he became wealthy his passion for gambling abated, but back in the days when he couldn’t afford it, it had been a serious addiction. He lost £20,000 in one evening at John Aspinall’s casino. He owed the bookmaker Alfie McLean – the subject of several of his finest paintings – £2.7m. He owed half a million to the Kray twins. The reckless nature of his gambling was reflected in his art, but once his paintings were making big money, the link was broken. “Gambling is only exciting if you don’t have any money,” he told Greig, in Breakfast With Lucian. “It has to hurt.”

But the thing he never, ever lost was his passion for painting – the urge to push himself further every time, never to repeat himself, to always accomplish something new. When he died, in 2011, aged 88, there was an unfinished portrait on his easel, of his long-standing assistant and confidante, David Dawson, and his beloved whippet, Eli. The words Urgent, Subtle and Concise were written on his studio wall. “It is the only point of getting up every morning,” he told Geordie Greig. “To paint, to make something good, to make something even better than before.” And in doing so, he created some of the most remarkable, arresting portraits of all time.

Freud at Chatsworth is at Chatsworth, Derbyshire, until October (www.chatsworth.org). Lucian Freud – New Perspectives is at the National Gallery, London, from 1 October to 2 January 2023 (www.nationalgallery.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks