The world of romcom queen Nora Ephron is a tonic for times like these

As the reality of yet another four years of Donald Trump begins to set in, Robert McCrum argues that Ephron’s comforting world of autumn landscapes, witty prose and whirlwind romances can help us through

In the weeks since Donald Trump’s storming of democracy’s citadel, there have been expressions of dread, hand-wringing editorials, and stunned columns. One New Yorker friend of mine, a mother of two, fled to Montreal and checked into a first-class hotel as the vote loomed. At the last count, she had taken to her bed with Netflix and room service, having switched off her phone. For all I know she’s still there.

In the weird catalogue of psephological panic, this is not exactly new. Many Americans suffered similar conniptions when George W Bush was elected in 2000. Several eminent literary figures swore to emigrate in protest, but very few actually upped sticks.

There is, of course, another view. Trump’s first term confirmed him to be one of the worst presidents in US history, although less sinister than fundamentally incompetent. He may be a vicious, far-right autocrat bent on revenge, but he’s also vain, lazy, ignorant, and often quasi-senile. America has known worse, though not often.

In these dire straits, I’m inclined to turn, for succour and counselling, to the free, liberal and uplifting spirits of the past, the great American romantics. I mean, why wouldn’t we want to smile through our tears? Why, for instance, wouldn’t we want to hear what Nora Ephron has to say?

The author of Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle and I Feel Bad About My Neck died too early from leukaemia (myelodysplastic syndrome) in 2012. Her ageless legacy in film and journalism, however, leaves many clues to the kind of witty and cold-eyed clarity on imminent existential dread that we might welcome just now.

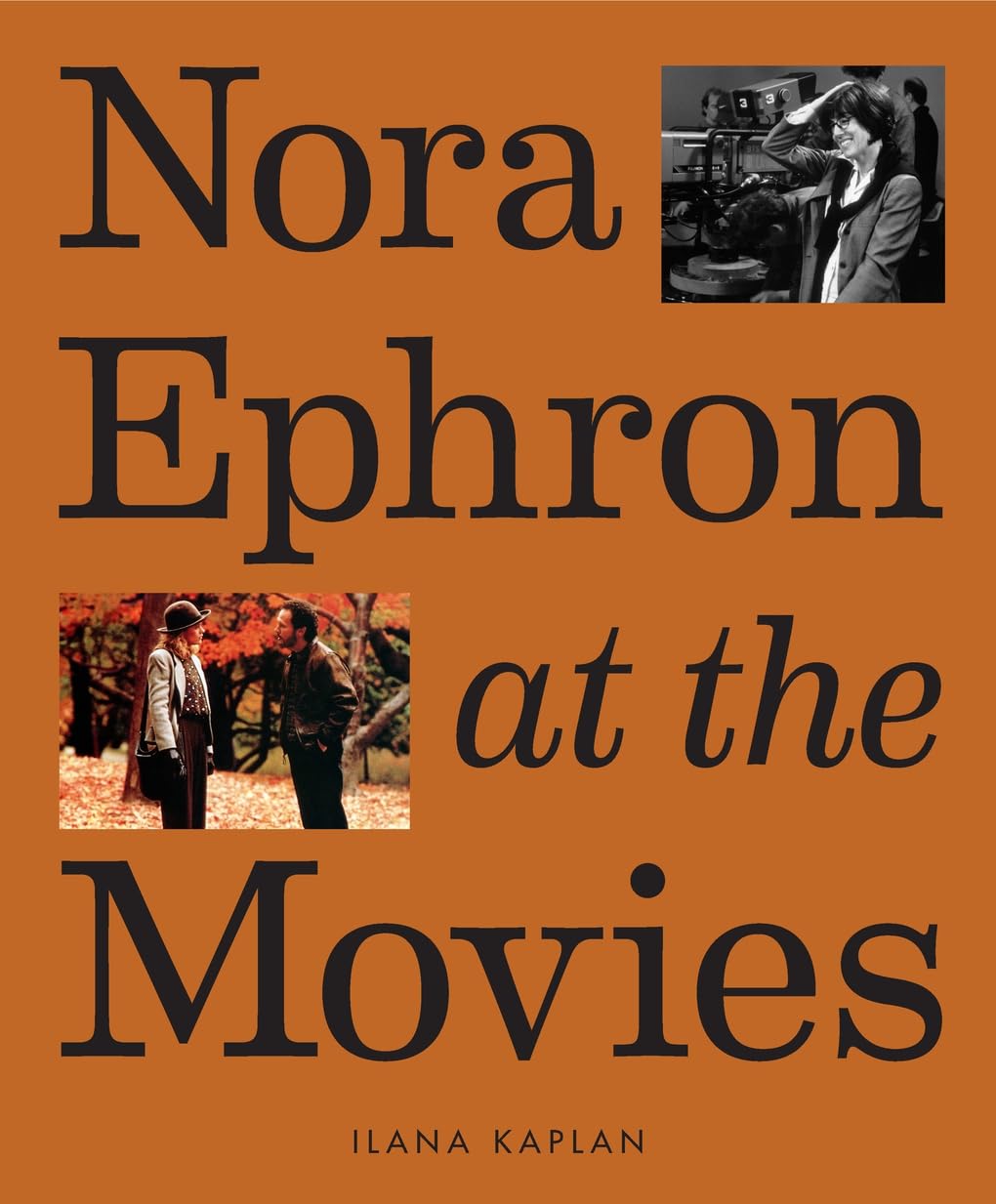

Ephron’s gift, as a writer, was to anatomise and exploit an insouciant ownership of her everyday experience. As Ilana Kaplan puts it in Nora Ephron at the Movies, her “talent for turning setbacks into success was unmatched”. Mining gold from dross, Ephron could extract revelations from ordinary life, the more ordinary the better. As Ephron famously observed, “Everything is copy.” (To her mother Phoebe, a Hollywood scriptwriter, this was a family saying.)

Mine is not an unbiased recollection. I knew Ephron before she became, as it were, herself. I remember an exquisitely gracious and composed young woman in the autumn light of New England; an unfazed observer of vanity fair who, as a journalist in Sixties New York – now I come to think about it – must have encountered Trump, the tabloid villain: a dodgy, attention-seeking property developer.

It was the autumn of 1981, and I was weekending on Long Island, staying in the Hamptons with Joe Fox of Random House. A tall man with a bearlike shamble, Fox was known as a charming, squash-playing clubman, and a backgammon fiend, but above all as a literary legend who’d worked with Truman Capote on In Cold Blood, as well as publishing Fran Lebowitz, Philip Roth and Peter Matthiessen, among many others.

Also staying at his beachfront property was this elfin, high-spirited divorcee, many years younger than Fox, who was currently his girlfriend. She introduced herself, almost shyly, as Nora.

In hindsight, I see that to a writer such as Ephron, for whom everything was raw material for her art, nothing would ever be wasted.

In You’ve Got Mail, an opposites-attract remake of Ernst Lubitsch’s romcom The Shop Around the Corner, Kathleen Kelly inherits an old bookshop from her mother, and Joe Fox (Tom Hanks), who’s the multimillionaire owner of the bookstore chain, wants to drive her out of business.

In the course of the next three days, knowing little of her backstory, and, more shamefully, even less of her reputation as a renowned magazine journalist, I soon came to discover in Ephron a brilliant and acerbic student of the human comedy, whose passion, after her typewriter, was her kitchen.

Ephron lived to cook. (Heartburn is as famous for its recipes as its revenge.) Better still, she loved to talk about food. In this present emergency, I’m fairly sure her first thought would be to start baking.

She was also instinctively wise, blessed with a savvy innocence of spirit that aerated every line of her prose with a lifelong metropolitan’s joie de vivre. At the moment we met she was irreconcilably separated from Carl Bernstein (of Watergate fame), and presumably at work on Heartburn, the wronged wife’s masterclass in getting even. When Harry Met Sally, You’ve Got Mail, Sleepless in Seattle, and the rest, were yet to come.

Like so many of the writers we admire extravagantly, Ephron always wrote as if there were other things to do than file copy. One collection of her essays has the simple, almost belligerently modest, subtitle: “And Other Thoughts on Being a Woman”. But it also contains “What I Wish I’d Known”, an anthology of her insights into the human condition.

Some of these are simply life-enhancing, from “You can order more than one dessert” to “Never marry a man you wouldn’t want to be divorced from.” Others are merely profound: “People have only one way to be.”

And then there are some sublime Ephron thoughts that can only elicit optimism and make you smile: “The plane is not going to crash”; “There are no secrets” and “The empty nest is underrated.” And (my favourite): “You can’t own too many black turtleneck sweaters.”

In Nora Ephron at the Movies, Kaplan’s focus is on Ephron’s films more than her prose, but she perceptively points out that what brings Annie and Sam together in Sleepless is their shared isolation and – yes – their experience of grief.

As well as her obiter dicta, Ephron left us some classic cinema moments that will always be an inspiration. There’s a way in which bad American politics often sponsors outstanding US culture. (Think of the prohibition years of the Twenties, and the dreadful presidencies of Harding, Coolidge and Hoover – a golden age of art and letters. When Coolidge died, Dorothy Parker, an outstanding literary figure from that era, murmured “How can they tell?”)

Imagine, if you will, that the US, in the age of Trump 2.0, does not go to hell in a handmade handbasket, but discovers some fresh resilience. There’s a new generation to oppose its creative innovations against the Maga trolls infesting the White House. Trump, as a lame-duck president, might become an object of renewed satire, with romcoms as a new kind of comfort.

Why not hunker down to watch When Harry Met Sally, and the rest, for those things without which we cannot survive? Autumn landscapes, cosy bedrooms, witty conversations, nice, comfortable clothes, crafty allusions to the golden age of Hollywood, moving pictures of some terrific food, and – how can we forget? – Meg Ryan in Katz’s Deli and the ageless echo of her inspired climax, with the perfect comic coda from an elderly diner at the nextdoor table: “I’ll have what she’s having.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks