The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Sigrid Rausing: ‘I like the idea that we – the living – are the ghosts haunting the dead’

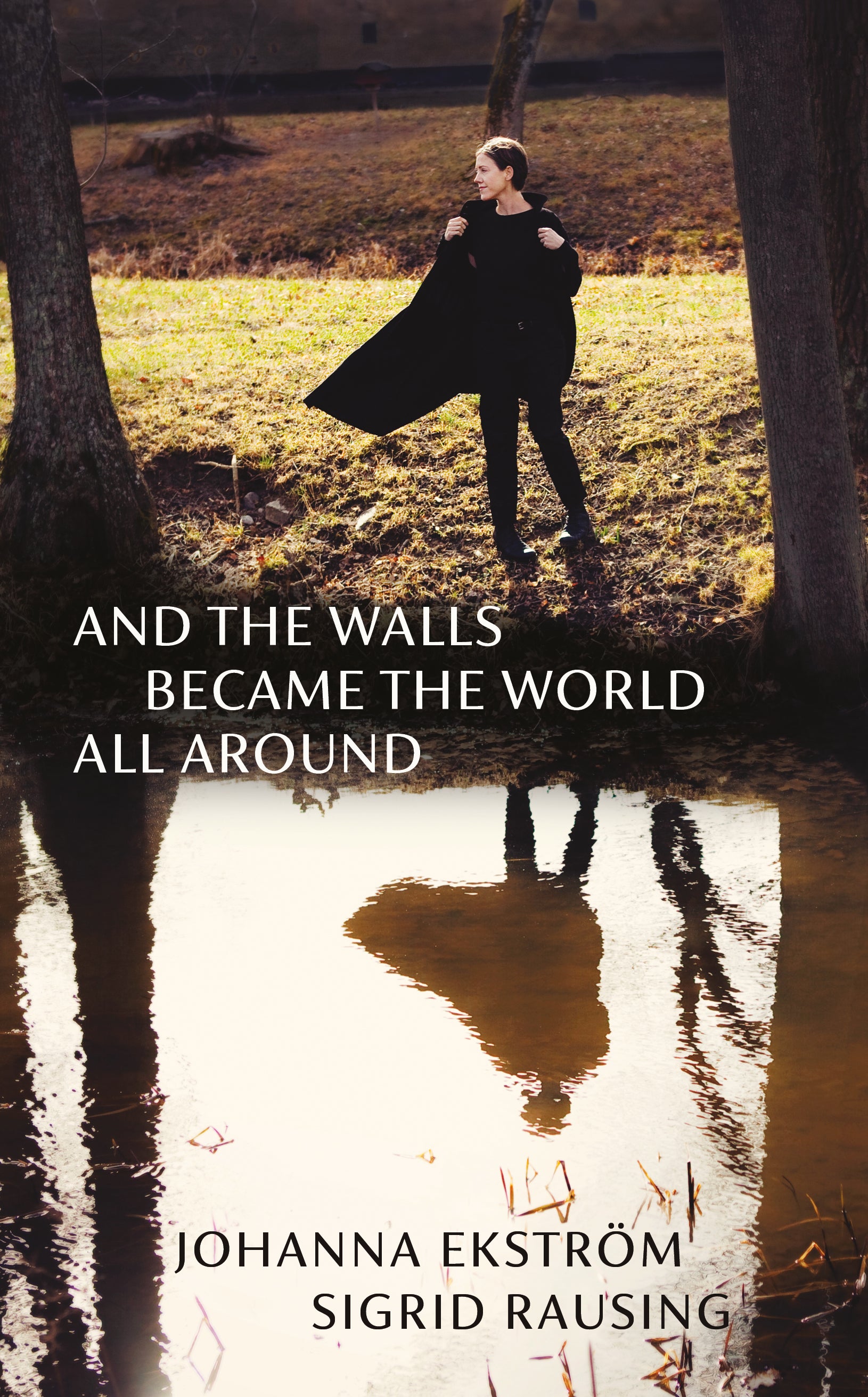

In 2022, Sigrid Rausing’s friend of 30 years, acclaimed Swedish writer Johanna Ekström, died of terminal cancer. After her death, Rausing completed Ekström’s request that she finish her final book, which became ‘And The Walls Became The World All Around’. Here, an extract shared with ‘The Independent’ lays bare their friendship, the life and death they shared, and its living legacy

My closest friend, the Swedish writer Johanna Ekström, was diagnosed with melanoma of the eye in September 2021. By the following spring, the cancer had metastasised to the liver, and her oncologist estimated that she had only two or three months to live.

She got a second opinion from a consultant in London, on Zoom. He confirmed the Swedish prognosis, advised her to eat what she liked and added that she might feel sad, or angry, or think, why me? Johanna, as I knew she would, found that irresistibly funny. “Well,” she said ironically, laughing at the screen. “Why not me?”

Johanna and I met in 1990. Her parents and mine knew each other a little, and her mother organised a birthday dinner for my mother in Stockholm (they were the same age). Johanna, ever competent and energetic, cooked for 20 or so people, with her then-boyfriend. I had brought my old friend Mark, and we all instantly recognised some quality of irony and longing in each other, a faintly under-parented sense of rebellion and hunger. Something in that first meeting – the irony, the camp, the gleefulness – stayed with us forever.

When I think of her now, I realise that it’s hard to describe a close friend because what one sees and thinks about is the feeling, the mood, the enduring microculture you generate together. Johanna was my closest friend, but she was also like a younger sister. Some sort of unspoken authority was vested in me, some sort of wild freedom in her.

As a writer, she was experimental and precise in equal measure. She played with words and syntax, but was rigorously attentive to her sentences.

Perhaps the quest for the right word or phrase in a conversation or in a piece of text was a slight obsession, cloaked in irony and humour. An exercise of diminishing returns if one had an end in mind, but she – or we – never did. The quest itself was the thing, the process of continuous exploration.

No right answers, only questions and observations that might suddenly turn into another register – equally authentic – of camp humour, performative femininity. However serious our conversations, in the end we’d laugh until we cried, or cry until we laughed.

After the terminal prognosis, I went to Stockholm to help. Time slowed down. Within a few days, Johanna was more or less confined to bed and ate only the tiniest portions of foods she craved or could bear to think about. A spoonful of semolina porridge with cinnamon, sugar, and a slice of strawberry or banana. A Japanese rice cracker with a sliver of avocado. A wafer.

I made notes during the hospice team visits, making sure I got the spelling and exact doses of the palliative medicines right. Johanna, already on morphine, cared not at all, fishing vaguely in the cotton shoe bag where she kept all her medicine. She was right, of course – none of it really mattered very much at this stage.

The week before she died Johanna showed me her last book, consisting of 13 handwritten notebooks, and asked me to edit and finish the text. I did, taking extracts from the notebooks and weaving in some of my own reflections. The book was published in Sweden in 2023, and within months I started my translation of it. The title (chosen by Johanna) And the Walls became the World all Around, is a quote from Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, showing how a room can become a whole world, or in Johanna’s case, the stage for the drama of her life and its end.

The book is a memoir of loss, which began as an ordinary writers’ notebook and then crystallised into something more exacting. Johanna originally conceived of it, I think, as an exploration of abandonment. She had experienced an intense relationship – a meeting of minds as well as of body – which disintegrated as her partner, N, retreated into a deep and silent depression.

The first part is a writer’s notebook, with quotes, cuttings, reflections on style and subject, dreams, memories and meditations on the pandemic. Some passages are marked “diary”, others “notes”. Johanna’s voice feels young and experimental – there are exclamation marks and capital letters, smileys and hearts. She’s happy, deeply in love with N, a translator and writer. A new relationship.

Soon, however, the euphoric tone turns. N fell into a depression, and Johanna describes her sadness and frustration. One senses the isolation of the pandemic in the background, but she has also found her subject: the notebooks now develop into a series of text fragments on the concept of loss, returning to deep feelings of bleak vulnerability, desolation and longing, intertwined with thoughts on literature and creativity.

The book is largely set during the era of the pandemic, and there is an unmistakable mood of the pandemic in the text – the close attention to minute details, the long meditations on the view from the window, the empty streets and the attention to soundscapes. A tree, imbued with a kind of life. Birds, observed like minor characters in a play. Dreams.

About halfway through the books – after many notes about exhaustion and curious visual disturbances – she received her diagnosis, and from that point on the book turns into reflections on another kind of loss – that of facing what turned out to be a terminal illness.

If Johanna didn’t think of the notebooks as a book from the very beginning, she soon did. From these handwritten fragments, the text would later be shaped. We don’t know what that book would have looked like, but it would likely have been quite different.

Her cancer diagnosis, for instance, slips in almost imperceptibly about halfway through the notebooks. Her symptoms – a profound exhaustion and changes to her vision – had by that time been part of her life (and of the notebooks) for so long that the diagnosis feels almost like a confirmation. “It’s raining gold in my eye,” she wrote weeks before she finally saw the optician. “All that gold, the stuff glittering in the corner of my eye.”

What does the fact that I saw it as beautiful rather than as a sign that there’s something wrong with my vision say about me?’

I helped to look after Johanna as she was dying. The days passed. She slept and I sat by the window. Sounds drifted up – voices, steps, the bark of a dog. Her voice turned weak and hoarse and at times she knelt on the bed, eyes closed, leaning forwards on cushions and pillows to alleviate the pain of the tumours, hard masses under the stretched skin of her abdomen. She sipped water and sucked on ice or frozen Coca-Cola, a cold cloth on her forehead.

She had a morphine pump attached to one arm and a port on the other where we could inject top-up morphine, liquid against nausea and tranquillisers. The syringes – three of each medicine, plus salty water to flush the line – were neatly lined up on a tray.

I cried again and again and was comforted by the very person whose imminent disappearance I was grieving. She held my arm and smiled; she leant back and closed her eyes, we sat in grief, in communion.

I read the newspapers as she slept and meaning escaped me. Sentences made no sense, I read them over and over. Johanna slept; so pale. She was increasingly absent. But every once in a while, she would come back – an ironic lifting of the eyebrow, some comment, something complicit between us.

Death, when it came, felt both abstract and concrete. The abstract quality (consciousness, a soul) disappears, the concrete body remains. Johanna’s body at the hospice was like an intricately detailed machine or a work of art. The enormous complexity of the body, all systems off.

A great silence.

Thoughts, images, sounds, heat, movement, electricity – all gone. Johanna’s short, clean hair bounced under my hand. Her eyes were closed; she smiled her faintly ironic smile.

The book is unfinished, and wilder and bleaker than anything she had published before. The playwright Simon Woods has spoken of the strange, harrowing beauty of her writing, and “that extraordinary combination of truthfulness and poetry and sensuousness and brutal intelligence that made Ekström so successful in her own language”. The writer Neel Mukherjee said the book is “absolutely its own thing, a haunting of the dead by the living”.

I like the idea that we – the living – are the ghosts haunting the dead, entangling ourselves in their lives, until we have to let them go to do their own thing. At times, working on this book, I have imagined, or thought I heard, or conjured up a memory of Johanna’s voice, and sensed a dialogue between us. Then the voice would fade, leaving me with 13 handwritten notebooks filled with dreams and fragments of text. The notebooks are archived in the Stockholm Royal Library now.

Our thousands of messages back and forth presumably still exist somewhere in the ether, digital archaeological signs, a footprint in the world. And Johanna is in me: a sensation somewhere between my heart and my throat, a mood, a word, a phrase, a hum.

A contour of my inner life.

And the Walls Became the World All Around by Johanna Ekström and Sigrid Rausing, published by Granta is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments