Is this new author really the next Patricia Highsmith and does The Safekeep live up to the hype?

The Dutch writer’s debut novel went to a nine-way book auction and Yael van der Wouden has been compared to Patricia Highsmith and Sarah Waters. But this tale of sex and guilt set in post-war Holland is dominated by feelings rather than story and atmosphere over plot. Welcome to the 21st-century novel, writes Robert McCrum

It’s an iron law of the book trade that when the publicity for a first novel by an unknown writer praises its presumed affinity with the work of established contemporary masters – the “awesome pathos of X”; or the “highly charged beauty of Y”; even “the wild intimacy of Z” – there’s usually big money at stake.

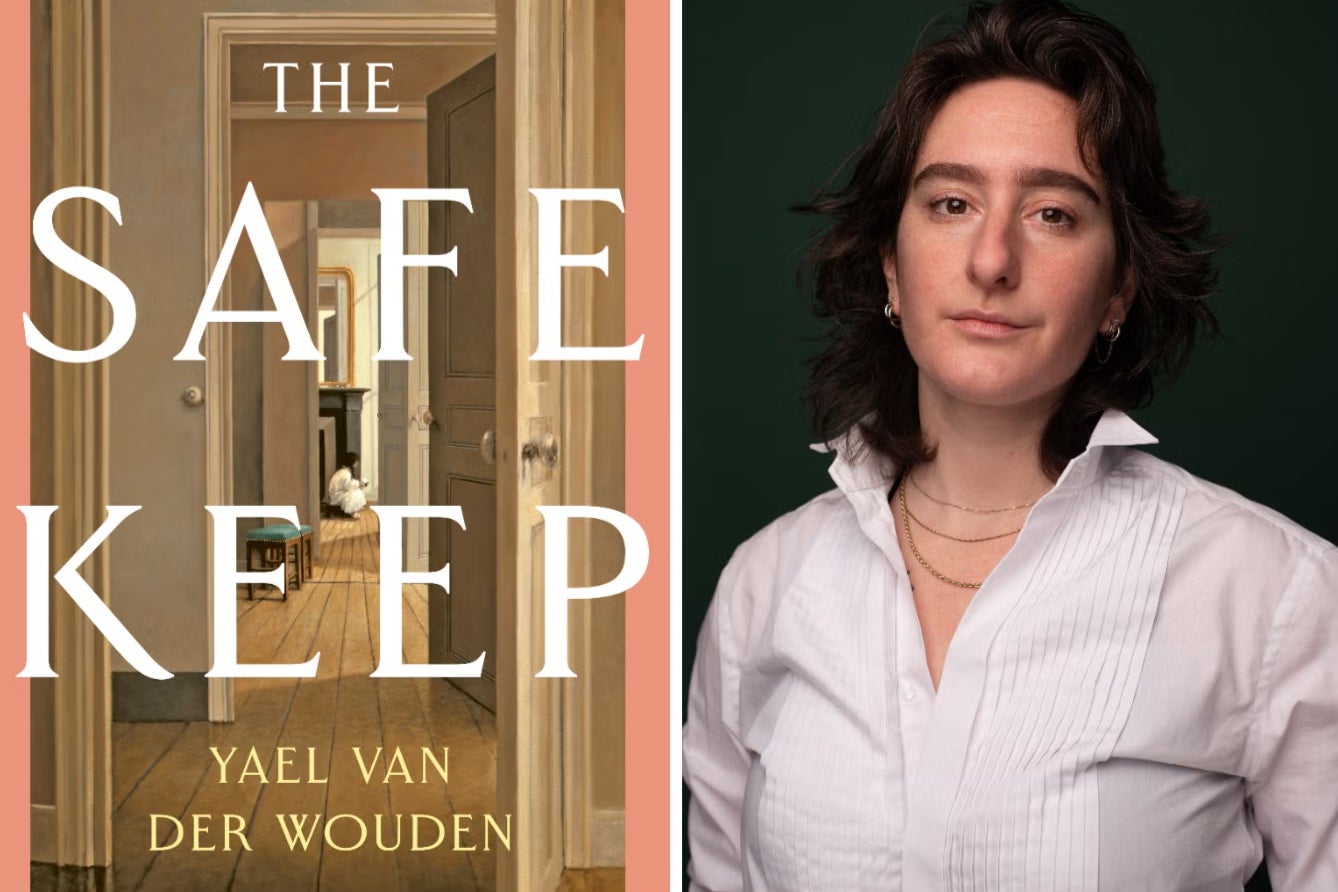

The Safekeep by the Dutch writer Yael van der Wouden, festooned with breathless hyperbole, and comparisons to the work of Patricia Highsmith, Sarah Waters and Ian McEwan, is a case study of publishers’ ballyhoo. Indeed, in promoting The Safekeep, Penguin Viking actually declares, with rare bravado, that this debut novel was acquired in “a hotly-contested nine-way auction”. (Translation: We forked out big time for this one). Nothing, in such boasts, could be better calculated to inspire an atavistic longing for the pleasures of solitary reading, unmediated by considerations of money or fame.

Enough about the hype. Actually to compare The Safekeep with Atonement et al is a surprising misstep for a world-class publisher. Yes, Van der Wouden transports her readers to an eerie country house in a remote, brooding landscape – and she does indeed subject a family of orphans to the tormented aftermath of the Second World War. But – it’s a big “but” – unlike McEwan and Waters, Van der Wouden displays no natural command of narrative, beyond a shadowy, vaguely sinister, backstory.

She has a scenario – the re-assimilation of persecuted Jews into the antisemitic communities of post-war Holland – but that’s a premise, not a plot. At best, her novel’s uneven exposition mashes up an atmosphere of unlikely paranoia with overwrought confusions of sex and guilt. Or, more generously, The Safekeep is an impressive debut whose strengths lie principally in mood.

A first novel is a statement of authorial ambition. Among aspiring writers in this genre, character is king, and novels with wonky plots increasingly familiar. Where new fiction (cf McEwan and Waters) used to be replete with “story”, now it tends to be dominated by feelings.

Welcome to the 21st-century novel. In fiction, amid present disruptions, we no longer cherish an appetite for plots. EM Forster, who famously said “Yes – oh dear yes – the novel tells a story”, has become a quaint Edwardian with moth-eaten sensibilities, quite as remote as a Regency writer like Jane Austen. Outside genre bestsellers, it’s now unusual for a literary novel to treat its plot with care. Contemporary novelists such as Van der Wouden are preoccupied with atmosphere, and psycho-social concerns such as the predicaments of sexual identity, or the horrors of the Holocaust.

The Safekeep opens in the Netherlands, 1961. We’re in the northeastern province of Overijssel, bordering the wasteland of the shattered Third Reich. The Second World War is over, but everyday life still suffers aftershocks. Isabel and her brothers are piecing together their lives as orphans in peacetime, confessing their survival instincts under the Nazis when their neighbours disappeared into the camps (“What time did I have to pay attention to anyone else? I did not keep track of where people went….”) Isabel clings to the security of her family home, which has assumed a character role. Post-war Dutch society’s adjustment to the transition from a brutal Nazi occupation remains a special trauma for a Calvinist community that takes pride in traditions of parochial decency that wrestle with visceral antisemitism.

Isabel, alone in her late mother’s property, devotes herself to normality. Van der Wouden’s evocation of airless still lives (“a moth under a dome of glass”) within this safe house creates a haunting, oppressive atmosphere of unspecified dread. When Isabel’s brother Louis comes home with his new girlfriend Eva, her fragile serenity is shattered.

Eva is Isabel’s polar opposite: loud, messy, vulgar and intrusive. We suspect – but are not yet told – that she is Jewish. Isabel’s hatred for her kicks in at once and when she begins to suspect that this unwanted guest is stealing from the house (spoons, knives, and crockery), her loathing turns this safe house into a bourgeois war zone.

EM Forster, who famously said ‘Yes – oh dear yes – the novel tells a story’, has become a quaint Edwardian with moth-eaten sensibilities, quite as remote as a Regency writer like Austen

Van der Wouden unfolds this part of her narrative with some skill: half-finished sentences; weird asides; flashes of sinister emotion; inexplicable exchanges; repressed allusions – a lot of space devoted to the unsaid, the unheard, and the unseen.

Charlotte Brontë famously wrote of the plot-driven English novel’s “suspended revelations”. The Safekeep, in contrast, becomes an asylum for disembodied desires. Van der Wouden’s characters – especially Isabel and her brothers – are notable for the energy they put into not saying how or what they feel, and in masking what they think. How, exactly, Isabel’s shameful jealousies morph into animal longing is never fully explored, but – when the mood breaks into sex – it explodes like a riot in a mortuary.

Without warning, Isabel now unravels in the grip of a same-sex “fever”. Again, we wonder at the transgressive thrill of an affair with a Jewish girl, but Van der Wouden – in thrall to her exploration of mood – is not much help. We follow Isabel being swept away by troubling sensations she does not understand until – hey presto! – she finds Eva’s diary.

Suddenly, all – or almost all – is explained. Eva is indeed Jewish, (“everyone would recognise her Jew face”), Isabel’s safe house had belonged to Eva’s family before they were shipped to the camps. Now it’s an object of obsession for both women. In the words of fiction’s oldest cliche, nothing is quite as it seems.

The same, sadly, might be said of The Safekeep. Its lyrical gifts are often notable, occasionally brilliant, but its reconciliation of character and story is improbable. Perhaps, for Dutch readers, Isabel’s agonised return of the family home to Eva holds a special magic. In our duller, and more insular climes, where memories of the war are unclouded by guilt, it reads like an ambitious but incomplete love story which was, regrettably, denied that all-important final draft.

’The Safe Keep’ by Yael van der Wouden (Penguin Viking) £16.99, pp. 262

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments