Simon Russell Beale triumphs in a treacherous genre: the thespian memoir

He’s one of the greatest actors of his generation, and this elegant love letter to Shakespeare is a precious glimpse into a free-spirited life – and it touches on some heartfelt universal truths, writes Robert McCrum

Stagecraft is also witchcraft, but it’s rare to have a magician of British theatre confide his secrets. A contemporary of Imelda Staunton, Alex Jennings and Ralph Fiennes, Sir Simon Russell Beale, who’s already been acclaimed by The Independent as “the greatest actor of his generation”, certainly has a résumé to match: 10 Olivier nominations, three Baftas and a Tony award, along with many prizes, and countless roles in film and television.

His true passion, however, is classical, obsessive and singular. Launched with a simple quotation from Hamlet, this remarkable book is one actor’s account of falling “in love at first sight” with William Shakespeare.

After a long and rich relationship – some 40 years – that has become, writes Beale, “an indispensable part of my life and work”, this elegant volume triumphs in a treacherous genre: the thespian memoir. The book is not an exercise in bardolatry, but rather a lucid, often brilliant, witty, and above all modest – even practical – account of “my time in [Shakespeare’s] company”.

As an actor, Beale possesses an uncanny and mesmerising ability to anatomise the mystery of a great part through the deconstruction of script and role. This is a gift that he translates from the stage to the page in his exploration of the playwright’s “uniquely hospitable” qualities as a poet, philosopher, psychoanalyst, entertainer, historian, mystic, and metropolitan crowd-pleaser.

In A Piece of Work, a clever and ambiguous title that’s at once precise and teasing, Beale paints an enthralling portrait of what “life and work” in the theatre might entail.

As an actor who has enjoyed important relationships with some of our finest contemporary directors (principally Deborah Warner, Adrian Noble, Sam Mendes and Nick Hytner), he takes the reader inside the rehearsal room to elucidate his own performances as Macbeth, Hamlet, Lear, Iago, Benedick, Malvolio and Prospero, among many others.

It’s a masterclass in Shakespeare by a player who confesses early on, with raw merriment, that he “loves being on stage”. In front of the footlights, or enjoying the vicissitudes of his own ebullient autobiography, here’s an artist who knows in his marrow how to hold an audience through a kind of radiant wit. As ever, that’s deftly achieved with a very light touch.

At the same time, this actor seems never to have been starstruck. In the making of his mature identity as a performer, Simon Beale, son of Sir Peter Beale (an army doctor who eventually became Surgeon General of the British armed forces) was blessed with two pieces of luck: his family and his voice.

The first became his anchor – the nurture of parents, brothers and sisters during a nomadic childhood with overseas postings; the second supplied a youthful grounding in the discipline of a chorister’s rehearsal routine. He writes that this “privileged” upbringing was “very sheltered”, but the record reads otherwise.

Family came with loss (the premature death of his sister Lucy); the demands of music instilled a deep grasp of his limits. Before he stepped on stage, life and singing were braided together; he treats both with respect and seriousness. (In the final pages of this memoir, we find a heartfelt note about his desire to make a television history of the concerto.)

He is always very much himself, with an infectious streak of self-mockery: one of many bone-dry comic asides describes a botched attempt at a theatrical rebrand as “Simon Beagle”. The upshot, in his work as an artist, is a kind of detachment that makes Beale an exhilarating comic actor, but also something of a lone wolf.

At Cambridge, he was part of a glittering generation that included Emma Thompson, Hugh Laurie, Tilda Swinton and Stephen Fry, but he’s at pains to establish that he “knew none of them well”. He might resist this comparison, but he shares with Shakespeare an insider-outsider ambivalence, running with both fox (many directors) and hounds (his fellow actors).

From his early life, he seems to have been blessed with an innate resilience. Sent away to school at the age of eight, he remembers “feeling more bemused than upset”. In his first letter home, instinctively searching for the mot juste, he reported himself to be “halfway between happy and unhappy”.

As well as displaying, in his attitude towards himself as a star, an impressive absence of vanity, there’s his basic modesty. Not many of his contemporaries would admit, as readily as he does, that “I am visibly overweight.”

It’s very much in character, for example, that he should report an early “West Country review” of his Hamlet, which punned: “Tubby or not tubby. Fat is the question.” Typically he concedes: “I was used to people writing about my weight. An actor’s size and shape are part of what people see on stage, and maybe I was fair game.”

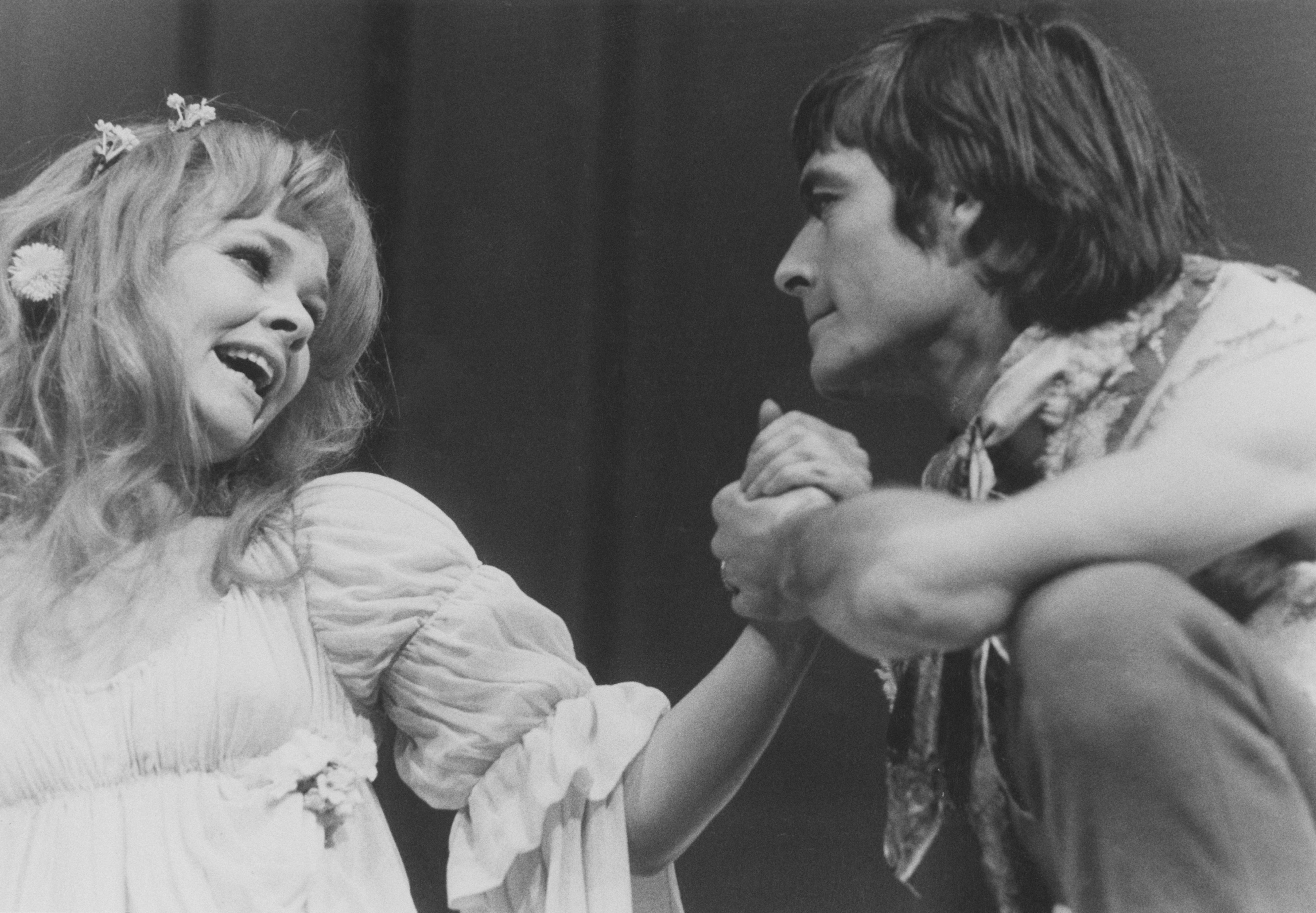

On stage, Beale almost always conjures an engaging atmosphere of “play”. In this memoir, which begins in a mood of reticence, his boyish innocence soon breaks through. Describing his performance as Benedick in Much Ado (opposite Zoë Wanamaker’s Beatrice), he recalls the scene in which (on the National’s Olivier stage) he was required to jump into an ornamental pool.

This, he writes, was “by a long way the most physically satisfying moment I have ever enjoyed on stage”. He describes the happy sensation of “being a 10-year-old again”, the experience evoking childhood memories of life in the far east.

His devoted audiences will know that what they see when Beale steps on stage is not only a great performer in his natural habitat, but also a free spirit in joyous communion with his liberated self. Just as important, he’s also a devoted student of the Shakespearean canon.

This is the great passion of an artist who can seem, in part, an academic manqué (with a first in English). Among several truly remarkable passages in A Piece of Work, his working analyses of Macbeth, Hamlet and Lear – as characters – are outstanding.

Consider, for instance, his reading of Macbeth, a role he “would like to play again” in a drama he interprets as a compulsive re-examination of children in relation to parents. His readings of Hamlet and Lear are also steeped in the lessons of the live production. Not for him the quasi-academic pose that claims that Shakespeare’s greatest plays are better read than staged, and that text trumps performance.

As you’d expect, A Piece of Work makes affectionate reference to many marquee names in recent British theatre (Fiona Shaw, Judi Dench, Benedict Cumberbatch, etc). Just as close to his heart is the roll-call of the major/minor Shakespeare parts he has played: Cassius, the King of Navarre, Thersites, Ariel, Edgar; even the young shepherd in The Winter’s Tale.

His analysis of Malvolio, Iago, Leontes, Prospero, Falstaff, and Timon of Athens is matched by his actor’s insights into their “stories”. He is not above confessing the influence of Coronation Street on his interpretation of a role.

Once, in a suggestive aside, Stephen Greenblatt, an American scholar of Shakespeare, observed that the playwright always wrote “as if he thought that there were more interesting (or at least more dramatic) things in life to do than write plays”. Beale’s “love affair” with Shakespeare, compelling as it is, has never blinded him to the appeal of a varied theatrical experience. He has been a great exponent of restoration comedy, performed regularly in Chekhov, and had many cameo roles in film, plus a lot of television. He has not, however, acquired a great screen presence.

Movies, he writes, are “another world”, and describes a conversation with a famous actor “of prodigious talent” (could this be Sir Ian McKellen?) who told him that “he planned to make his name in movies and then come back to the theatre later in his career, when he would be assured of great parts – and full houses” – which was “precisely and triumphantly what he did”.

Beale is at home in his skin as a stage performer. This, to many English actors, is a higher calling than movie stardom. His instinct, he reports, is that he would “probably spend most of my career in the theatre, which felt like home, rather than in the movies, a scary terra incognita”. Just once, in A Piece of Work, does he seem to hanker for better recognition on screen, when paying tribute to Armando Iannucci for the role of Lavrentiy Beria in that brilliant black comedy The Death of Stalin.

The alchemy of Shakespeare that Beale administers in these pages derives from Hamlet’s “words, words, words”. Few contemporary actors understand as well as he the minutiae of thought and emotion that can be encrypted in print – or the risks inherent in this magical experiment. “Words,” he writes in closing, “are slippery.”

That, for him, is “the ever-present thrill of Shakespeare”, and the greater professional thrill of analysing Shakespeare. On stage, from time to time, some actors do achieve something he describes as “a universal impersonality”. Such moments are rare, transcendent, and unforgettable. When you close A Piece of Work, as a dazzled reader lost in the solitude of these pages, I believe you will glimpse this “universal” sensation – in black on white – for yourself.

‘A Piece of Work: Playing Shakespeare & Other Stories’ by Simon Russell Beale (Little Brown, £25.00) is published on 5 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks