The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

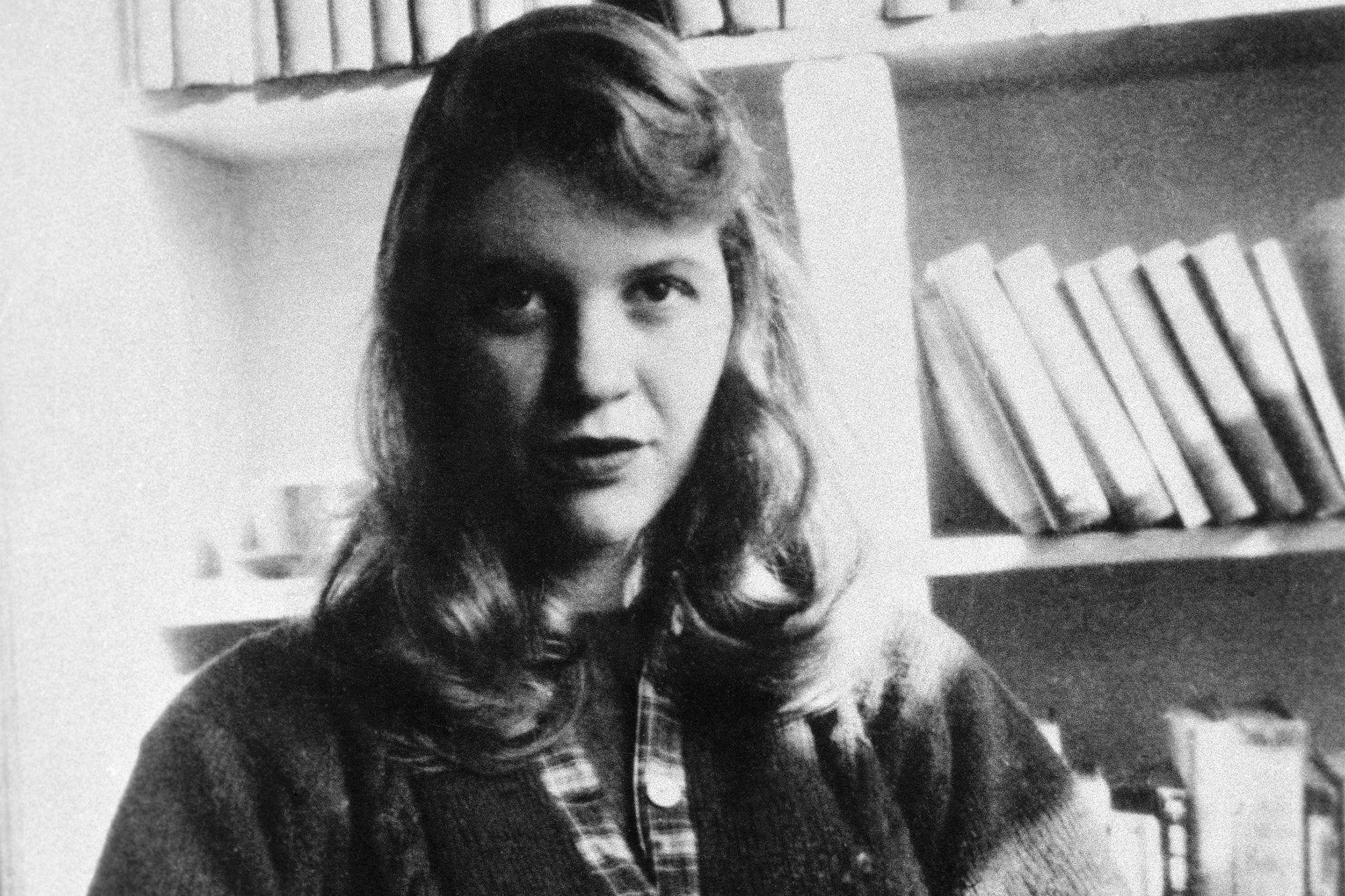

The monstrous myths that have hijacked the life of Sylvia Plath

The latest book on the poet casts her in a world of agony and repressed domestic violence at the hands of her husband Ted Hughes – a dark lord of a callous patriarchy. It’s a familiar tale, says Robert McCrum, who knew Hughes, but turning a bitter marital breakdown into a mythical yarn does her a great disservice

It was Boris Pasternak, author of Dr Zhivago who sounded a sombre warning about what happens in the terrible event of someone taking their own life: “We have no conception of the inner torture which precedes suicide.”

And in this latest book on Sylvia Plath, we have an original tale full of attitude whose origins must be traced to one of the most notorious suicides of all. More challenging and complex still, on top of a classic enigma, we have a new take on an old story of a tragic love affair that continues to torment writers and readers in equal measure, from the bright revolutionary skies of East Coast America to the back-ways of Hampstead Heath or Primrose Hill.

What began as a bitter marital breakdown has, over time, become a monster of myth and counter-myth that haunts every new generation.

It is a story that first took root in Camden Town, that leafy, yet grey, part of London known to Dickens. In the autumn of 1962, an expat American poet and novelist and mother of two, recently separated from her partner, a celebrated English poet, moved into the second-floor flat of a house previously occupied by WB Yeats.

A place whose associations seemed pre-ordained, it was here that the 30-year-old began to write as she’d never done before, in a fever of self-awakening. We now know that both she and her estranged husband, Ted Hughes, were in the antechamber of greatness. He had found his voice, and been acclaimed for it, with The Hawk in the Rain. She, having taken the rooms in Fitzroy Road, was “living like a Spartan”, to complete the Ariel poems that would also make her famous, composing new work in the cold blue dawn, gripped by the belief that she must write “to free myself from the past”.

As the year turned, however, she became trapped in the worst English winter for 150 years. The weather, which I remember from childhood, was brutal. Heavy snow falling on Boxing Day made travel impossible. By new year, the country was paralysed. Water pipes seized, with many power cuts. Everything ran short, while the freeze went on and on, a merciless offensive driving everyone to the limit.

“Weight for weight”, wrote her friend, the critic Al Alvarez, “plumbers were as expensive as smoked salmon… The lights failed and candles, of course, were unobtainable. Finally, the heart failed.”

For a better insight into this young poet’s breakdown, her ex-husband’s letters tell us most of what we need to know about the terrible events of 11 February 1963; the day Sylvia Plath gassed herself “at about 6am”.

She had gone upstairs to her two sleeping children (aged one and two) and left a plate of bread and butter and two mugs of milk in case they should wake hungry before the au pair arrived. (There’s an unverifiable suggestion that she had expected to be discovered before it was too late.) Then, according to the most reliable accounts, she returned to the kitchen, sealed the door and window with towels, opened the oven, laid her head in it, and turned on the gas.

A month later, Hughes wrote to his mother-in-law: “I don’t want ever to be forgive... if there is an eternity, I am damned in it.”

Despite this apt prediction, Hughes could never have known how, in Plath’s savage moment of self-destruction, she had become the goddess of a doomed future that would swiftly translate into a shared and tormented posterity, their unquenchable myth.

Hughes’ failed marriage was a kind of curse, a divorce braided with a suicide became a damnation. In 1962, led by Alvarez, the poetry world on both sides of the Atlantic – a palimpsest of vanity, grandeur, irony, ambition and pride – was soon buzzing with a tragedy to which few could be indifferent, and none impartial.

Next to Pasternak, Hegel reminds us that the true understanding of life’s mysteries only comes at the end of the day. The owl of Minerva spreads its wings at dusk; even personal tragedies get narrated late and backwards.

Within two decades of Sylvia’s death, an astonishing Plath-Hughes literature had blossomed in orchidaceous profusion: letters and diaries, literary criticism, Alvarez’s The Savage God (1971), and at least six duelling biographical studies (The Silent Woman; Bitter Fame; The Haunting of Sylvia Plath; Method and Madness; Rough Magic; The Death and Life of Sylvia Plath). Almost all of this was refracted through the hot lens of women’s liberation. By the 1990s, it had created, for better and worse, the first afterlife of Sylvia Plath, in which (in Janet Malcolm’s description) she became the “silent woman”, subordinate to Hughes as the guardian of her estate.

That traumatic cycle ended in October 1998 with the premature death of Ted Hughes at 68 and the sensational publication of Birthday Letters, his quasi-posthumous last word, soon after. In my recollection, it seems to have been a point of honour with him never to initiate a conversation about Sylvia, but, in this, he finally revisited his terrible marriage to achieve a belated redemption.

To some, Hughes remains a troubling and incorrigible proposition, but the man I recall as a Faber poet was gracious, reticent, generous and supremely dignified. At the graveside, Seamus Heaney said: “No death outside my immediate family has left me feeling more bereft. No death in my lifetime has hurt poets more. He was a tower of tenderness and strength, a great arch under which the least of poetry’s children could enter and feel secure. His creative powers were, as Shakespeare said, still crescent. By his death, the veil of poetry is rent and the walls of learning broken.”

The owl of Minerva is also a bird of omen. Much of this elegiac reverence gets short shrift in what we might call Plath’s second afterlife, approximately 2001-2017. From the millennium to the emergence of the MeToo movement, Sylvia Plath’s unforgettable presence and reputation have been supercharged by a mythic life story that has passed, with many gossipy scandalous accretions, into the collective unconscious.

Plath’s fate and her achievement – her greatness – have inspired the making of a literary icon: the patron saint of confessional poetry whose true genius has become smothered by the legacy of her suffering as an “abused woman”. Today, a new generation of Plath readers is repossessing her story to undo what they see as “the silencing of Sylvia Plath”, a crime against her genius that seems to inspire a weird mix of sound and fury.

Loving Sylvia Plath, subtitled “A Reclamation”, by Emily Van Duyne, is a case study from this genre, a bold and idiosyncratic volume that takes the traditional reader of Ariel into a world of agony and ecstasy, tormented biography and repressed domestic violence.

When the Plath and Hughes tragedy first began to be anatomised, it was conventional among critics such as Alvarez to keep life and art rigidly separate. Here, however, we find Van Duyne’s polemical fervour appropriating Plath’s life not only to transact passages of contentious literary criticism but also to console her own sub-literary distress. Art and life have now become inextricably mashed up in ways that would astonish the forgotten gatekeepers of Plath’s first afterlife.

The task of loving Sylvia Plath turns out to mean making a strong identification with her struggle: Van Duyne confidently mobilises her own autobiography to illuminate Plath’s tragic fate. Here, the relationship with Hughes, an unquestionably difficult marriage (no one disputes this) becomes a case study of IPV (“intimate partner violence”).

If this might seem, to some readers, a shaky foundation on which to construct a new literary critical interpretation, Van Duyne’s passionate intensity admits no doubts. As early as page 13, she declares that her insight into Plath’s predicament “was born of my own experience as a survivor of intimate partner violence with a man who is now the long-estranged father to my older son”.

This shadowy ex, of whom we learn almost nothing but his penchant for IPV, haunts these pages as the principal validation of Van Duyne’s right to conduct her anatomy of Hughes the sexual predator.

In Van Duyne’s version of Plath’s 21st-century afterlife, Hughes is the dark lord of a callous patriarchy. Sadly, many of her more fruitful insights into the psychodrama of the Hughes-Plath marriage get tarnished by the kind of scholarly paranoia that asks, “What stories [have been] struck from the archive?” Worse, in place of the biographical excisions, Van Duyne supplies her own experience (“Between 2010 and 2012, I lived with a violent drug addict… etc”) or, as she puts it, began “using my body to help tell the story of hers [Plath’s]”.

When we read – in closing – that Van Duyne’s IPV has achieved a rare communion with Plath, as the poet who “took me seriously”, it’s hard not to conclude that this well-intentioned but self-absorbed attempt at a better understanding of an impossibly dark myth has – like everything else in Plath’s afterlife – been cursed by her tragic suicide.

Other quasi-literary and biographical interpretations of Sylvia Plath’s life through the prism of her death will surely appear in the run-up to her centenary in 2032. I have no doubt these will present different and even stranger rereadings than this latest offering.

Her ghost is not yet at peace.

Losing Sylva Plath: A Reclamation by Emily Van Duyne, is published on 23 August by WW Norton & Co

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks