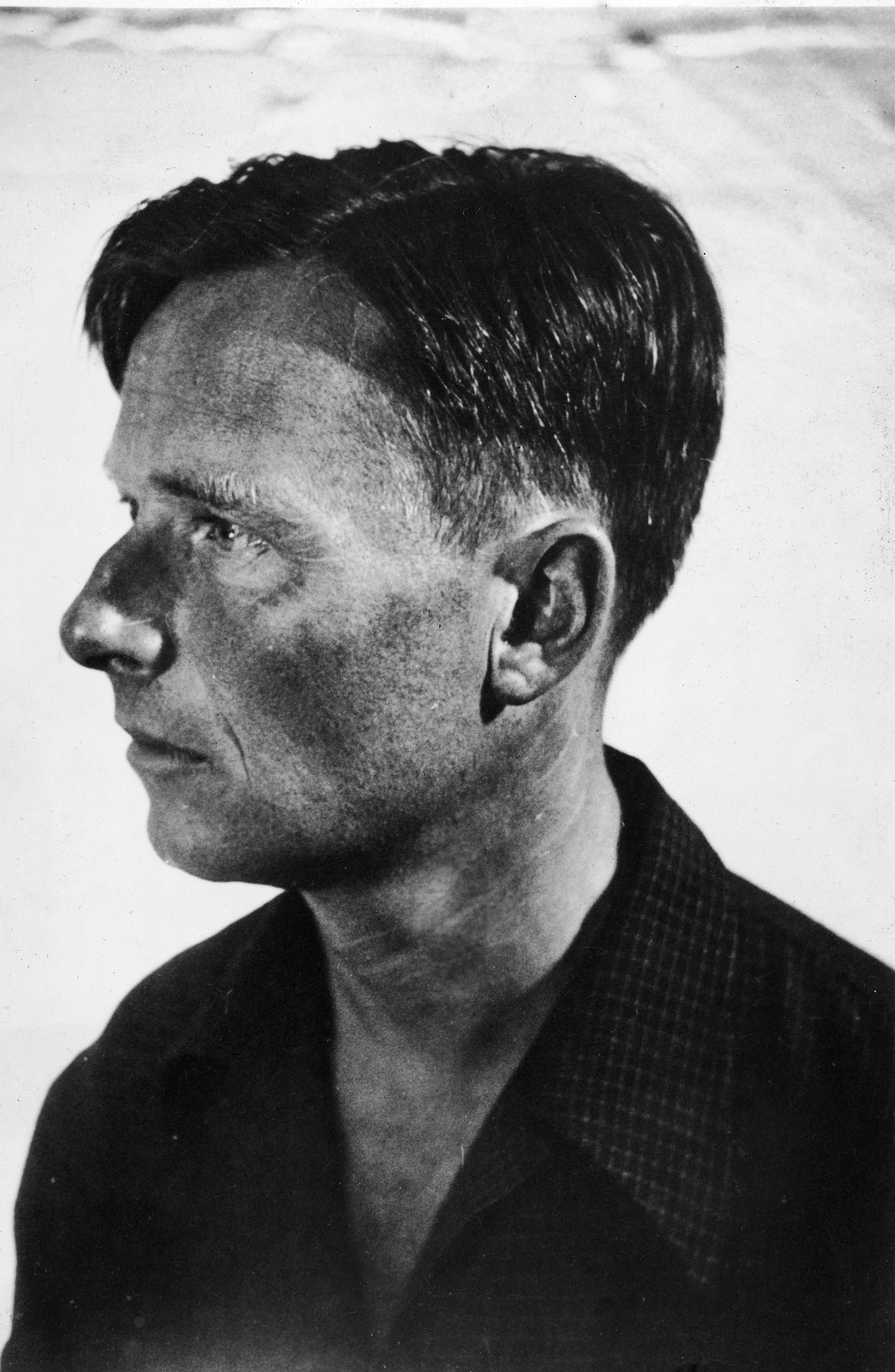

Lust before love: finally the full story of the wild boy magic of Christopher Isherwood can be told

Inveterate partygoer, sometime lover of WH Auden, and literary conjurer of Thirties Berlin, Christopher Isherwood was deemed to hold ‘the future of the English novel in his hands’. So what is left to say about him? A new biography by Katherine Bucknell finds plenty, says Robert McCrum

It was Christopher Isherwood’s sometime lover, the poet WH Auden, who dismissed the biographer’s art with “A shilling life will give you all the facts”, adding a vicious parody of the life-writer’s obsessions: abusive father; broken home; youthful struggles; deeds of greatness; and so on. As it happens, it became Isherwood’s gentle riposte to this sarcastic summary to offer the example of a brilliant career devoted to worldly affections, empathy, and gay sex: a romantic Modernist’s self-dramatisation of the Bloomsbury credo “Only connect.”

Furthermore, although there are plenty of Isherwood “facts” (classic writer on Thirties Berlin; inspiration for Cabaret, wunderkind gay novelist), these are often rather beside the point. It’s what Isherwood embodies in himself (gaiety, wit, tolerance and humanity) and also in his writing (a limpid style of clarity, strength, simplicity and candour) that matters.

For this idiosyncratic life, Katherine Bucknell is the perfect biographer. She is an Isherwood scholar who has devoted some 30 years to editing three volumes of Isherwood’s Diaries (1939-1983); also The Animals, his letters to his lover Don Bachardy, and an edition of Lost Years, another memoir of 1945-51. Why – you might ask – would she want to revisit such a well-documented career so meticulously curated by its own subject? Moreover, what’s left to say? Long before his death in January 1986, Isherwood – with crystal, and often comic, brilliance – had already had the last word. Or had he?

It’s the triumph of Christopher Isherwood Inside Out that Bucknell’s version not only transcends all previous attempts but also convincingly unites the astonishing scope and variety of the writer’s English and American lives into an enthralling, and finally moving, portrait of an artist who, as much as any writer of the 20th century, wrought a decisive and lasting influence on his life and times.

As Gore Vidal puts it, with green-eyed candour: “In every generation there are certain figures who are who they are at an early age: stars in ovo. People want to know them; imitate them; destroy them. Isherwood was such a creature.”

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood, like the hero of a classic English novel, was born in August 1904 to a life of wealth and privilege that seems, in Austen’s words about Emma, “to unite some of the best blessings of existence”.

According to Bucknell, “Christopher Isherwood” was, from the beginning, “the central character in a story” – the tale of his life. A child of Cheshire landed gentry, he was clever, sensitive and articulate, and was raised in a comfortable home amid settled security. His parents Frank and Kathleen competed in their love for him; above all, his gifts were equal to his ambitions.

This Edwardian boy would mature with a panoply of diminutives that emphasise his profound Englishness. When, in the 1950s, Isherwood conceived the novel about an Englishwoman that became A Single Man (1964), he wrote in his diary: “This morning we went on the beach and discussed The Englishwoman, and Don [Bachardy] ... made a really brilliant simple suggestion, namely that it ought to be The Englishman – that is, me.” He described this insight as “very far-reaching”.

Bucknell observes that Isherwood always “worked on the boundary of fiction and non-fiction”. Here, he had much in common with three equally brilliant English writers, born his contemporaries: Graham Greene (October 1904), Evelyn Waugh (October 1903), and George Orwell (June 1903). Like Orwell, Isherwood would wrestle with his identity, through sex not class, in search of a better life and a better self. He would become “Christopher”, the third-person character who occupies so much of a lifelong quest for authenticity, his signature achievement.

The Great War also contributed to his life story. Isherwood’s charmed boyhood was shattered in May 1915 when, during the battle of Ypres, his father Frank was annihilated by shellfire, a fate confirmed by his dog-tag. Kathleen’s grief forced the 10-year-old boy into the shocking realisation that his mother had loved her husband more than her son. Henceforth his affections would roam elsewhere.

Isherwood’s first role after this trauma would be as a Sacred Orphan, dedicated to the memory of his father’s sacrifice. At first, unable to bury his father’s body, he learnt to bury his emotions. No longer compelled by his mother’s feelings, he could begin to experiment with the assertion of a mature self, and with finding his voice as a writer. In the discovery of this vocation, his history scholarship to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, became an experience he loathed, and then rejected with his famously frivolous, comic repudiation of the tripos exam. Soon after his flight from academe – to Bucknell his “first act of self-realisation” – he would arrive in Berlin.

Just as Eric Blair found his new identity, down and out in Paris and London, and became “George Orwell”, so the ex-student Christopher Bradshaw-Isherwood discovered himself in 1920s Berlin, exploring his “need to get back into the dark, into the bed, into the warm naked embrace”. During the run-up to the Nazi seizure of power, he became “Herr Issyvoo”, discovering, in his obsessive, self-devouring lust, the truth that “boys can be romantic”.

In the marriage of art and sex, Isherwood found his theme. With contemporary reticence discarded, it’s only now that the full story of the Cosy Corner, a hangout for the working-class Berlin boys where “Herr Issyvoo” could lose all inhibitions, can be told, inside out.

Bucknell’s portrait of her subject’s lust for boys in 1930s Berlin is fearless, explicit and comprehensive, a homoerotic footnote to Christopher and His Kind (1976), replete with the joys of “rubbing”, “rimming” and “f***ing”. Occasionally, Bucknell tries to out-Issyvoo Issyvoo. “Love affairs,” she writes, “had become part of Isherwood’s repertoire of nervous tics, like smoking and masturbating.”

Gore Vidal says that, with his celebrated declaration of intent (“I am a camera”) on the opening page of Goodbye to Berlin, Isherwood “became famous”. These four words, indeed, would shape a whole life. After the publication of Mr Norris Changes Trains (1933) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939), he would never be the same again. His character Sally Bowles would inspire the hit play that eventually became the mega-hit musical Cabaret (1972).

An inveterate partygoer and book reviewer, habitue of the Cafe Royal and BBC broadcaster, he is glimpsed, like an exotic species, flitting through the pages of other writers’ letters and diaries. Isherwood, exclaims one, “seduced more boys than any other individual in Berlin”. Vidal, grappling with his friend’s elusive spirit, writes that Isherwood crops up “as a principal figure” of the times, but admits that he’s “not an easy figure to fix upon the page ... Nothing is harder to reflect than a mirror.”

Charm is a notoriously fickle, English quality. Bucknell delves as best she can into her subject’s “wild boy” magic, but she can hardly compete with Isherwood’s command of the Thirties. Meanwhile, before the Second World War broke Isherwood’s life in half, the London literary establishment had reached a verdict. For W Somerset Maugham, Isherwood “holds the future of the English novel in his hands”. To Cyril Connolly, he was, with Orwell, the “superlatively readable” master of colloquial English prose. To others, he’d joined the company of EM Forster.

Now, the novelist who’d identified so famously with the camera broke with Britain at war and went to Hollywood to become a screenwriter. “Christopher”, sometimes “Chris”, is the character who dominates the second half of his life’s tale, an icon of gay Englishness who acts out his story as a celebrated homosexual and devotee of Swami Prabhavananda and the Vedanta movement, a new religion, against a California sky. In his monastic house in Santa Monica, with the Pacific a few blocks away, Isherwood conducted a highly camp flirtation with American independence and the thrill of the second chance – breaking loose from Blighty amid the scent of eucalyptus and sea air.

In a highly revealing sentence at the end of this very long work, which must wrestle with the inequality of this life’s passage, Bucknell breaks cover to declare that her book has been “the adventure of a lifetime”. This ambiguous phrase (whose lifetime?) is also her coded thank you to the man – Isherwood’s life partner Don Bachardy – without whose blessing this “inside out” portrait could never have been attempted. Caveat emptor.

In 1953, the Isherwood who’d placed lust before love for so many years met young Don on Valentine’s Day, and fell in love. He was 48; Bachardy was 18 – a detail that scandalised Isherwood’s English friends. The vicissitudes of their relationship as “Dobbin” and “Kitty” – on which A Single Man becomes a haunting, even bitter, commentary – would not only shape the diminuendo of Isherwood’s creative life and define the second half of his career; it would also make Bachardy a promiscuous and highly strung co-conspirator.

During the Fifties, Bucknell retreats from the high ground of her subject’s brilliant first act. The life’s tale of 1904-45 becomes the wife’s tale, and closes in 1986 with Bachardy, in the antechamber to the morgue, executing a harrowing sequence of portraits depicting his lover on his deathbed. Inside out, with a vengeance.

‘Christopher Isherwood Inside Out’ by Katherine Bucknell (Chatto, £35, pp. 838)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments