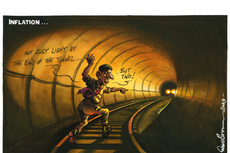

The Bank hikes interest rates again – but the end of the pain could finally be in sight

The cycle of rate rises is coming to an end – it will be all eyes on inflation and wages to determine how quickly they go into reverse, writes James Moore

“Are we nearly there yet?”

Mortgage holders, small businesses and just about anyone with an interest in the future health of the UK economy could be forgiven for copying the child’s traditional car journey complaint at the Bank of the England’s Threadneedle Street HQ. And loudly.

After the fourteenth consecutive UK interest rate rise – by 0.25 percentage points to 5.25 per cent this time – it’s fair to say that we might be at the beginning of the end as regards this interest rate cycle. But we’re not quite there yet. Sorry, but that means there may be a couple more small rate rises to come. It all depends on the next couple of inflation releases and how closely they conform to expectations.

The good news, so far as borrowers are concerned, is that the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) did at least fight shy of imposing a second consecutive 0.5 point rise, something which a significant minority of the City (the split was roughly 70/30 in favour of 0.25) had been expecting.

Two external members - leading rate hawk Catherine Mann and her occasional ally Jonathan Haskel - went so far as to dissent and vote for that. Swati Dhingra, a model of consistency, repeated her cry into the wilderness that a pause is due. She voted no change making for a 2-6-1 split.

The real power, however, is with the Bank’s internal team. As usual, it voted en bloc for the middle path alongside debutante Megan Greene, a new external member of the MPC who had made hawkish noises in speeches before she took her seat.

The MPC is now expecting inflation to fall to 5 per cent by the end of the year, which is good news for Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt, who could yet claim to have met their promise of halving inflation come Christmas time, credit they won’t deserve given that it’s the MPC and (especially) Britain’s borrowers who’ve been doing the heavy lifting.

But the MPC remains concerned about wage growth and the increasing price of services, which has remained stubbornly high.

The TUC has long said that Britain needs a pay rise and it is hard to argue with that given the brutal assault on living standards caused by extended price spike we’ve been living through.

But it puts the frighteners on the MPC. It has repeatedly made clear its concerns over a potential wage price spiral. Not always diplomatically. The Bank’s well remunerated governor Andrew Bailey and especially its chief economist Huw Pill have both put their foot in it with some notably ill advised comments on the subject of pay the past. This despite the fact that, as Dhingra has noted, wages have been falling in real terms for three in every four workers. The hard fact is that the current cycle of rate rises won’t end until the pace of pay growth slows.

That is ultimately expected to happen because for a start, as the MPC acknowledges, its actions are going to cost jobs. The unemployment rate forecast to rise to 5 per cent by 2026, from its current 3.9 per cent, because the economy is going to slow. Enough to qualify for a recession? You need two consecutive quarters in negative territory for that and we’re not there yet. But it could happen.

Some of the consumer’s resilience will inevitably take a hit as the remainder of fixed-price mortgage deals unwind and people face sharply higher bills to keep a roof over their head. Let’s not forget the plight of small businesses, which are facing a perfect storm. The Federation of Small Businesses reports that low-cost finance has “almost entirely disappeared” and the base rate rise will only make that worse.

“Yesterday, the Prime Minister claimed that small businesses are ‘booming’ – but we’d class what he said as more of an aspiration at this point, unfortunately,” said its national chair Martin McTague.

It is still just about possible to foresee a temporary pause in rate rises at the next meeting. It would help a lot if the next inflation figure (due in a couple of weeks) starts with the figure six. June’s figure of 7.9 was less than most forecasters had expected, the first time that’s happened in months. A repeat performance would be just the ticket. I wouldn’t, however, bet the house on it.

As for when things start to move the other way, easing the pressure on everyone who’s borrowed so much as a fiver, I still wouldn’t expect to see that until the middle of next year.

But those looking for a bit of optimism might care to pay heed to a school of thought which holds that it takes time for rate rises to have an impact. We’re only really at the beginning of the economic squeeze they will cause. It could get quite severe and that could force the Bank to move more quickly than most forecasters currently expect.

The political pressure on the MPC is mounting and while it members would tell you they’re focussed purely on economics, they’re not competley immune to that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks