In what was the best piece of news the prime minister has received in some months, the Bank of England has issued a central prediction that inflation will fall to 4.9 per cent by the end of the year. This means that it should comfortably hit Rishi Sunak’s “five priorities” promise to halve it from the double figures it was running at in late 2022.

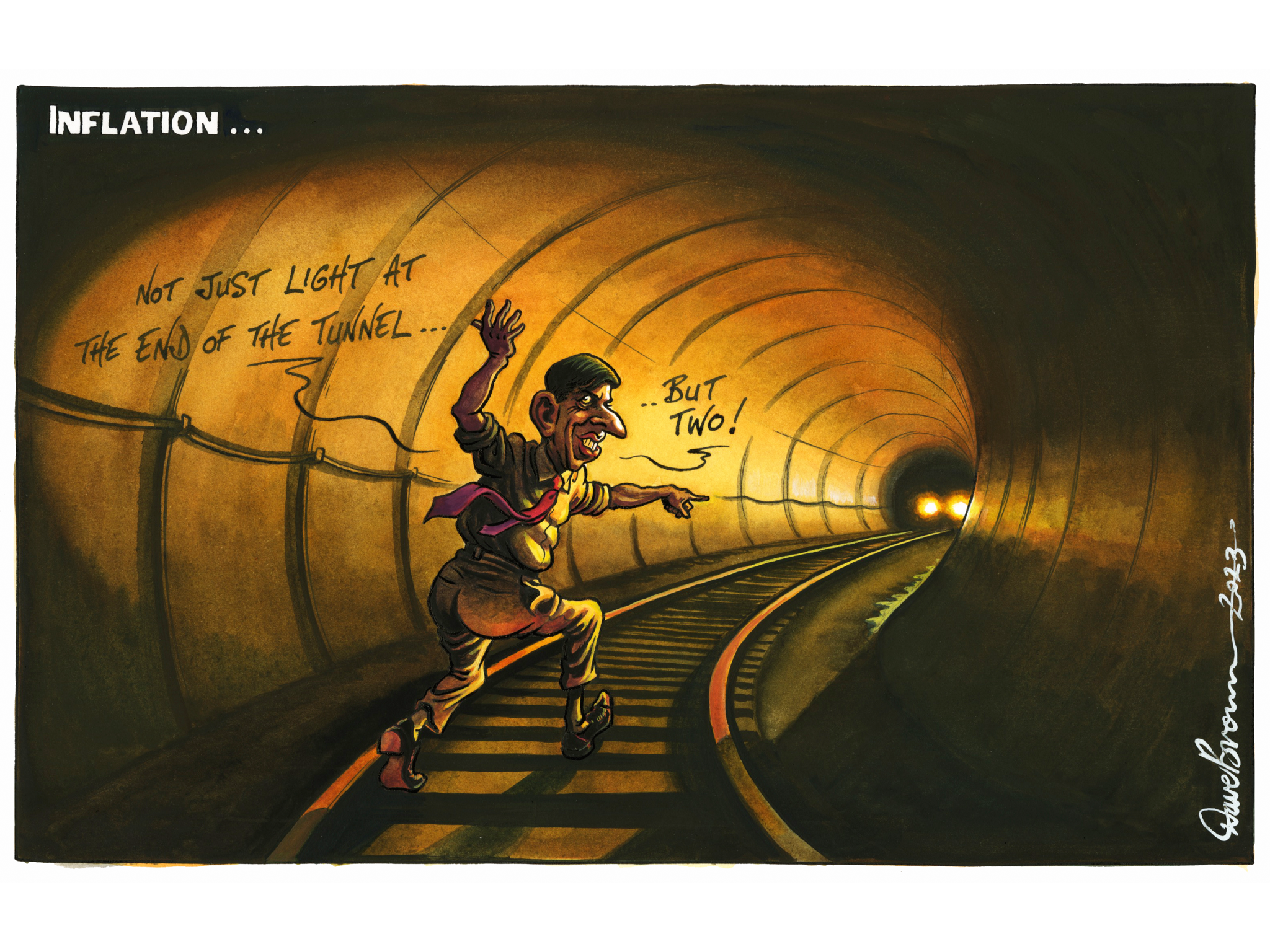

Informally, the inflation target is the most important one for the government, because it is so key to easing the cost of living crisis, stabilising interest rates and making the public finances more sustainable. It is light at the end of a long, dark economic tunnel.

Politically, Mr Sunak and the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, will claim that their strategy of placing inflation at the centre of policymaking has been justified. Despite previous disappointments and some quietly simmering frustrations in government circles about the performance of the Bank and its governor, Andrew Bailey, things at last seem to be going Mr Sunak’s way.

Come January 2024, Mr Sunak and Mr Hunt will claim themselves vindicated. It would be in poor taste to point out that they have been merely reversing the disastrous effects of the Truss-Kwarteng experiment, managing the continuing depressing effects of Brexit, as well as the aftermath of the Cameron-Osborne austerity era and more than a decade of mismanagement.

However, there are risks, and there is a price to pay for this improvement in inflation. The war in Ukraine, for example, still has the potential to push food prices higher on a global scale, because the region is such an important source of grain, edible oils and fertilisers. Continuing shortages of labour, post-Brexit, may keep wage costs uncomfortably high for business, and they will try to pass those costs on to shoppers. Recent experience has certainly suggested that UK inflation is “sticky”, and has become to a certain extent endemic, via the tight labour market. Britain has the worst inflation performance among the advanced economies, and looks likely to continue to do so, even if Mr Sunak’s (modest) personal target is met.

The biggest risk – and the one that will exact a painful political price – is that the Bank’s squeeze on households and businesses could tip the economy into recession. Recent poor retail sales figures and a pronounced weakening in the property market certainly point to a slowdown, and the authorities must hope that such trends don’t turn into a housing slump – something that would have the most profound consequences for the economy and the government’s slim chances of re-election.

One thing that may be confidently predicted for 2024 is that there will be no boom, and Mr Hunt’s scope for radical tax cuts is non-existent. The perilous state of the public finances – now lumbered with an unexpectedly high cost of debt servicing – and the financial markets will permit only the most timid and symbolic of pre-election giveaways. That, in turn, will exacerbate the tensions about direction of travel within Mr Sunak’s party.

The Bank’s outlook for growth has been downgraded since the last one in May; and the central projection is for minimal growth accompanied by falls in investment, a weakening property market and a rise in unemployment. This suggests that, with inflation still relatively high, wage rises will continue to fall behind prices, and the pressure on the cost of living will persist, even if it becomes less painful.

But with such a fragile outlook for growth, it wouldn’t take much bad luck to push the economy into a shallow contraction and mild recession, if not worse. The Bank openly admits that inflation will be higher than the official 2 per cent target until 2026, and the relative strength of the services sector may mean a continued trend to higher interest and mortgage rates next year.

It’s also worth noting that interest rates are an increasingly weak weapon against inflation in an economy where the structure of the mortgage market has been transformed since monetary policy became the preferred policy instrument, about a half-century ago.

In those days of early monetarism, interest rates would affect a large proportion of the population holding moderately large mortgage debt at floating rates fairly rapidly. Now, because so many have laid off their debts, and because so few active mortgages are variable, the brunt of the punishment is borne by a narrow group of society – typically those in their thirties, with necessarily larger loans in the South East, and not yet at their peak earnings power. By contrast, their parents and grandparents, mortgage-free and watching their savings income increase, may be feeling rather better off.

Interest rates are also an ineffective way to increase the supply of labour in an economy. It might be fairer if fiscal policy were used to tax the better off, and migration policy adjusted to allow more workers in. Both such alternatives, though, are utterly unrealistic politically.

Stripping the jargon away, things will still feel tough in 2024. Whether the economy grows or shrinks marginally, it will feel like there isn’t much money around, and business will tend to stagnate. Obviously, this is an unpromising prospect for any government in an election year, and particularly for one that will have been in power for 14 years or more.

Mr Sunak will probably hit his personal inflation target, and enjoy his moment of triumph, but it won’t feel that good to the rest of the population. He should certainly not expect a surfeit of thanks when election day eventually rolls around.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments