‘By rebuilding the cathedral, I’m rebuilding myself’: The craftsmen working to replace the Notre Dame spire

Nearly four years after the gothic masterpiece burned down, hundreds of craftsmen are working round the clock to return the cathedral’s spire to its former glory, writes Rick Noack

Almost four years after a fire gutted the over-850-year-old Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the monument is slowly being pieced back together. With a reopening date set for December 2024, workers are carving statues and cranes are lifting stones to repair the vaulted ceilings. And about 200 miles away, at an industrial wood workshop in rural eastern France, carpenters are assembling what will become the cathedral‘s new spire.

“The dimensions are gigantic,” Philippe Villeneuve, a chief architect of Notre Dame’s reconstruction, says.

Workers on Thursday were climbing up ladders and carefully assembling the spire’s future base, an X-shaped structure made of thick oak beams, measuring 50ft on its longest side.

“I often think of it as the nuclear core of the construction site,” Villeneuve says. “There’s absolutely no room for mistakes.”

The spire itself, cone-shaped and lead-covered, will reach a height of more than 300ft once all the elements have been assembled at the cathedral in Paris.

It would be fair to say that France, if not much of the world, is watching.

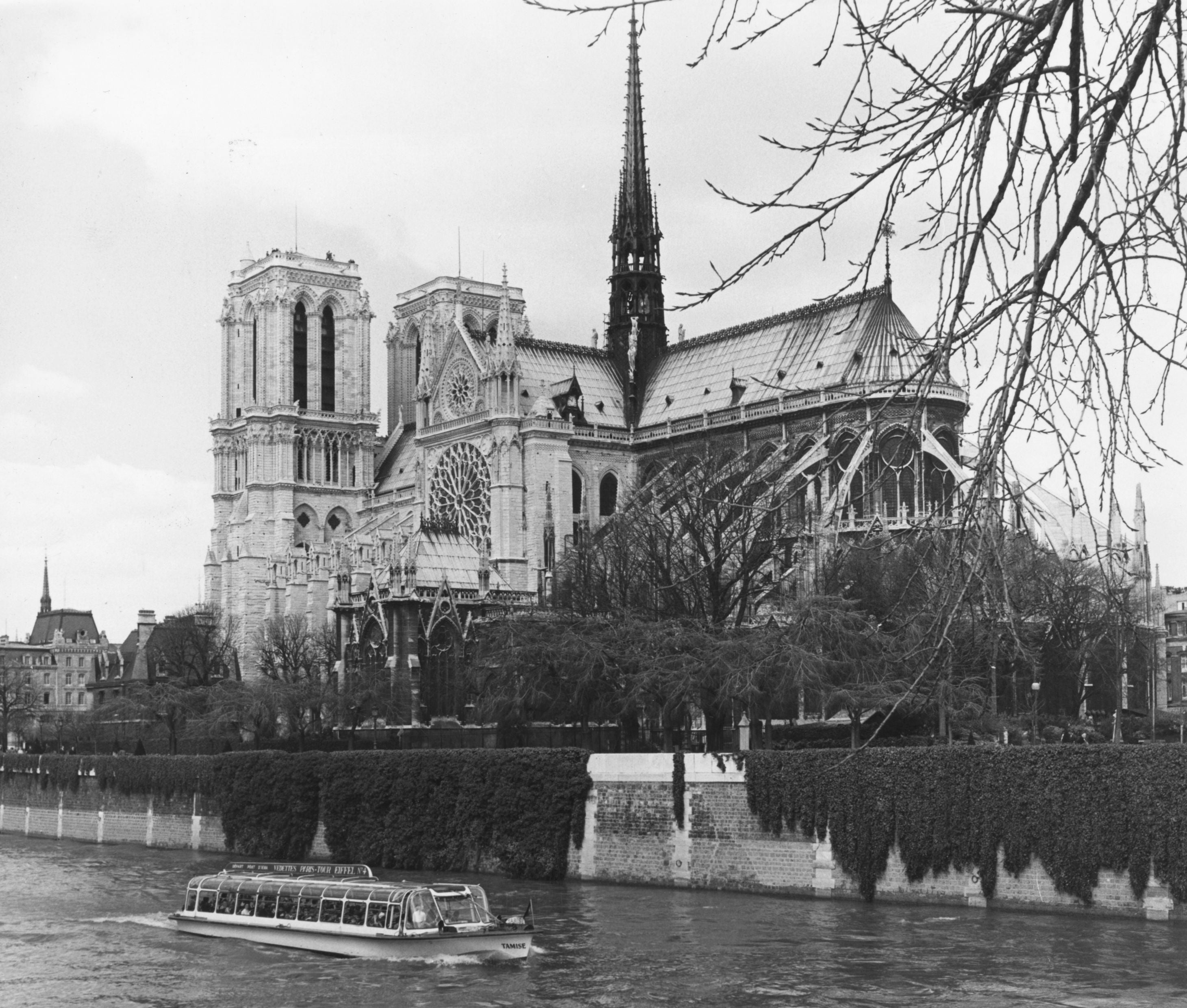

The day of the blaze, 15 April 2019, will remain deeply engraved in French memory. As the spire collapsed, bystanders watching from the banks of the Seine river cried in silence. Millions followed the scenes in disbelief on television. Many French people still know exactly where they were and what they did when they heard the news.

“People couldn’t believe that it was possible – but unfortunately, it was,” recalls Dany Sandron, an art historian, who was among the crowds near the Seine and has worked on the construction site in the years since.

Notre Dame had been Paris’s most-visited tourist attraction, a masterpiece of Gothic architecture that lured more than 12 million visitors each year. But many people in France also embraced it as a cultural symbol, a visual anchor of Paris and a reminder of the Catholic traditions that undergird a proudly secular republic.

The cathedral’s iconic bell towers and elaborate stained glass withstood the flames. The Crown of Thorns, which Jesus purportedly wore during his crucifixion, was saved. But the roof collapsed, the medieval wooden interior was obliterated, and many artefacts were lost. The cause of the fire remains unknown.

Standing in front of Notre Dame that night, with smoke still billowing, president Emmanuel Macron vowed, “We will rebuild this cathedral.” His hope was to have it ready for visitors by July 2024, when France is hosting the Summer Olympics. But French officials say they are now aiming for the end of 2024.

“We will have two extraordinary events in France in 2024: the Olympic Games and the reopening of Notre Dame,” Jean-Louis Georgelin, the French army general tasked with overseeing the project, told journalists touring the wood workshop on Thursday. “The image of France is at stake in those two events.”

Villeneuve had been involved at Notre Dame before the fire, overseeing repair work since 2013. He wasn’t in Paris when the first fire engines rushed to the cathedral. But as soon as he heard, he jumped on the last train from the Atlantic coast.

“Luckily, I didn’t see the spire fall,” he said. “I don’t think I really would have recovered from that.”

In the following days, he and his team identified the most destabilised parts of the cathedral. As workers secured the building over the following two years, French architects, church representatives and politicians sparred over how to rebuild.

Some architects proposed reconstructing the collapsed roof as a greenhouse, or with stained glass instead of wood, or even replacing it entirely with a swimming pool. Not all of those proposals appeared to be serious, but advocates of a modernised design argued that the fire presented a chance to start anew, as previous generations of architects had done.

Notre Dame has undergone multiple transformations in its more than 850-year history. Through the centuries, the cathedral’s windows were widened and the flying buttresses reconstructed. After an old spire was removed over safety concerns in the 18th century, the cathedral went decades without its now most iconic feature. Under the architectural leadership of Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Notre Dame was subject to such dramatic changes in the 19th century that many scholars today say the building is more representative of that period than of its medieval origins.

Successive French presidents have been eager to leave their imprint on the centre of Paris, personally championing projects such as the Louvre pyramid and Pompidou Center. Macron, who had been elected on a platform of renewal two years before the fire, suggested a “contemporary architectural gesture” in the new spire design. But after a backlash – including a threat by architect Villeneuve to resign – he embraced a reconstruction closely replicating the original.

It will look different in some ways, though.

“Before the fire, we had a very dirty cathedral – walls that looked almost black or dark grey, because of the pollution from candles and smoke,” says Sandron. “Now, the colour of the stones is very light.”

Aurélien Lefevre, who leads a group of carpenters working on the reconstruction, says the project remains a challenge – but not one that is insurmountable. Problems can appear at any stage, which is why the test run of assembling the wooden beams this past week was a crucial step.

“We’re not immune to forgetting something,” Lefevre says.

Especially for younger carpenters, being part of the project may be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, he says.

Nearby, dozens of carpenters saw, hammer and polish wooden beams made from centuries-old oak trees. More than 1,000 carefully selected trees from across France have been felled for the reconstruction.

On the edges of the workshop, the skeletons of walls for local construction projects have been pushed aside to make space for the project that will remain the priority over the next months.

Outside, Villeneuve rattles off a list of project milestones: “The galleries are finished, the north and south transept done.”

Other parts – including the spire, decoration, vault and furniture – remain works in progress. But after the shock and devastation of 2019, every sign of progress matters to those who care deeply about the building.

“It’s balm on my scars,” Villeneuve says. “By rebuilding the cathedral, I’m also rebuilding myself.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments