A legacy of hatred: The repugnant history of the Ku Klux Klan

As a new documentary for PBS explores the poisonous ideology of the KKK, we must never drop our guard, writes James Rampton

It’s an image that cannot fail to shock. Sporting his organisation’s trademark conical white hood, a member of the Ku Klux with an insouciant cigarette dangling from his mouth is holding up a Black baby doll for the camera. It has a noose around its neck.

This picture sums up the terrifying racist power that the Ku Klux Klan still projects, 158 years after its foundation. The Klan has been driven for all that time by a pernicious white supremacist philosophy.

Its dark history stretches from Klansmen routinely lynching Black people who had the temerity to try to vote in the 1868 post-Civil War elections, through the era of racial division in the Deep South during the 1960s, when young white children would parade at demos carrying banners proclaiming “Segregation Forever” and Black victims would have the letters “KKK” carved into their stomachs, to the spittle-flecked young men giving Nazi salutes while screaming “White power” and murdering civil rights activists at demos today.

The KKK’s influence has waxed and waned over the past century and a half. But it is undergoing something of a renaissance in the deeply fractured post-Capitol riots America. There are still a disturbing number of people in the US quite prepared to support the KKK and defend white supremacy. The message the Klan still wants to broadcast to the world is: be afraid... be very afraid.

But how did the Klan begin? What has powered it over all this time? And how does it still hold so many people in thrall to its repugnant race-hate ideology?

The group’s origins lie in the ashes of the shattered South in the aftermath of the Civil War. The conflict resulted in 4 million slaves (out of a total population of 9 million people in the Southern states) being freed.

This emancipation came as a huge blow to the white inhabitants of the South. As Linda Gordon, professor of history at New York University, puts it: “Slave owners were terrified by the end of slavery. They were terrified economically that they would lose their very cheap labour force. But they were also terrified that African-American people would start to demand the rights of citizenship.”

In reaction to that threat, a group of Confederate veterans began meeting in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1865. They formed a drinking society, initially to share stories of the good old days in the slave-owning South.

They named their society the Ku Klux Klan. Some have said that the founders chose that phrase because it replicates the sound of a shotgun being cocked. But it is more likely that the first two words come from the Greek for “circle”: kyklos. They added the word “Klan” for the sake of alliteration.

David Korn-Brzoza, the director and writer of The Ku Klux Klan: An American Story, an illuminating new PBS America documentary about the organisation, says their “branding” was cunning from the outset. “Very quickly, the words Ku Klux Klan became a well-recognised sign for their group. It was already a kind of sophisticated marketing for what they were.”

The group started by playing pranks, dressing up in scary costumes and putting on weird voices to frighten freed slaves who they thought were highly superstitious. But their antics soon escalated into something far more sinister.

In 1868, the KKK began terrorising freed slaves by burning churches, courthouses and polling stations. They also placed themselves outside voting booths in order to stop Black people exercising their democratic rights. More than 1,000 Black people were murdered in the four weeks leading up to the 1868 presidential election.

As well as a hideous legacy of slavery, lynchings were commonplace, too. Gordon explains the significance of this. “It's important to understand that in lynching an individual, their goal was to intimidate the whole mass. That is what terrorism is.

“To a very large extent they succeeded because while slavery was abolished, the complete subordination of African Americans continued. They were unable to get decent jobs, unable to have education, unable to have healthcare. It was a successful campaign by a small terrorist organisation.”

Horrified by the Klan’s activities, Congress voted to clamp down on what was known by now as the “Invisible Empire”, and by 1872, it was officially declared destroyed.

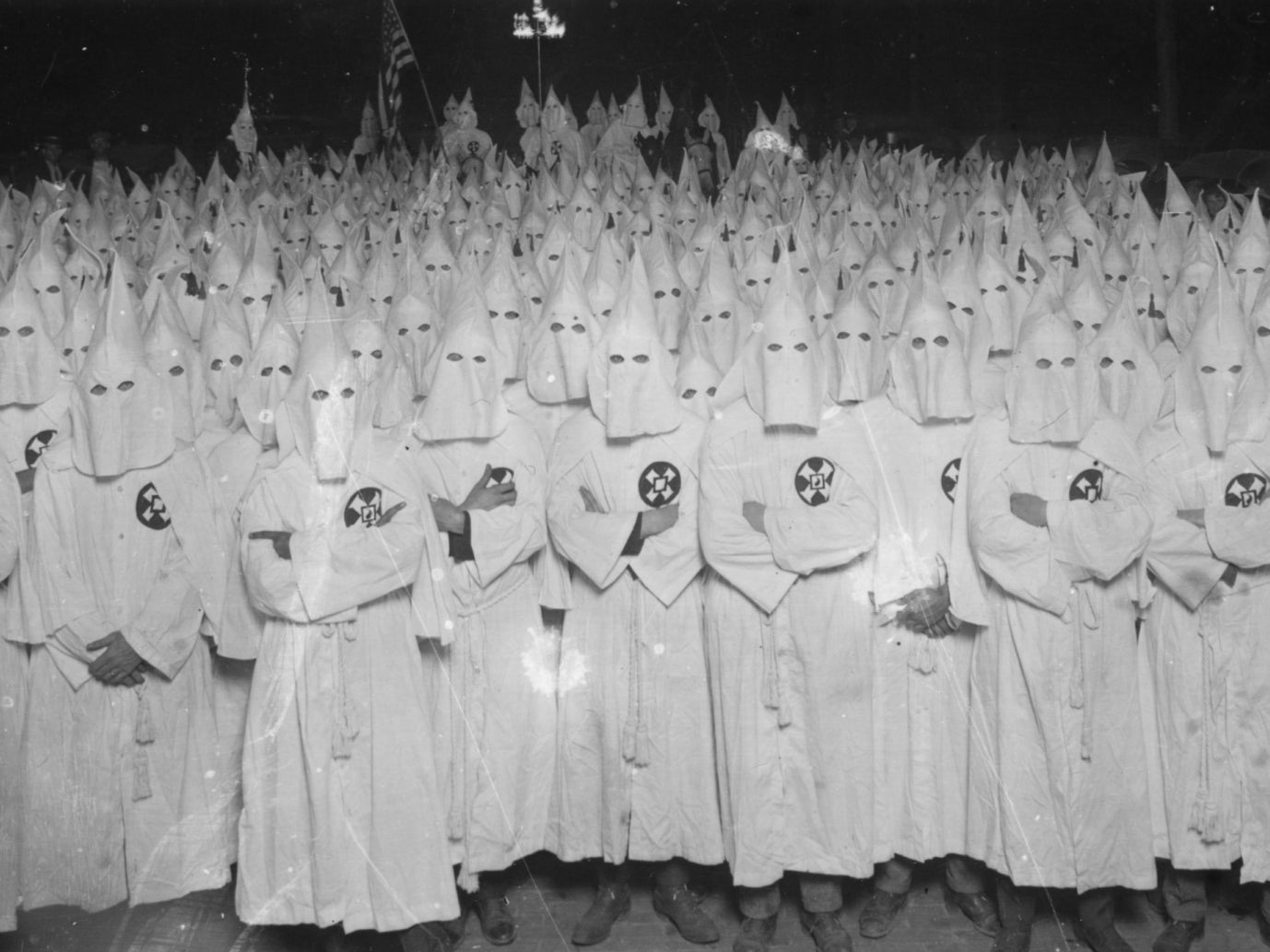

The KKK remained in abeyance until – of all things – the release of a movie. DW Griffith’s 1915 film, The Birth of a Nation, depicted the clan not as criminals but as avenging angels of justice. The film, originally entitled The Clansman, also cemented in the public consciousness the KKK iconography – the white hoods and robes and burning crosses – which still sends a chill down spines today.

Audiences flocked to this mendacious, absurdly romanticised portrayal of the Klan. More than 50 million Americans saw this outrageously slanted, three-hour advertisement for the organisation.

The movie was universally praised. Even president Woodrow Wilson, widely viewed as a progressive, said the film was “like writing history with lightning”.

“The first ever blockbuster movie was completely racist,” exclaims Korn-Brzoza, whose documentary is available on Freeview Play.

Gordon outlines the appeal of The Birth of a Nation: “Black people are threatening to kidnap and rape white women all over the place. The denouement of the film is quite terrifying. It shows all these Black people like barbarians just running wild across the land and the brave Ku Klux Klan defending morality and white womanhood. That position of defending white womanhood is very, very central to the Klan.”

The movie flattered the ego of Klansmen. “For a certain type of man, it made you feel good. You were heroic and a super patriot doing something to protect your society and country.”

More damaging yet, The Birth of a Nation became the predominant way that American people understood the history of the South.

A canny white supremacist pastor called William Joseph Simmons capitalised on the surge of interest by revitalising the KKK. He hired two publicists who concocted a pyramid scheme to sell membership of the organisation. Recruiters could keep 40 per cent of the initiation fees. It made Simmons seriously wealthy. He counted his riches in a multi-million dollar mansion.

As white Americans began to feel threatened by a new wave of immigration from Europe, support for the Klan grew extremely quickly. It soon became woven into the very fabric of American society. It had its own records, bands, radio stations and newspapers with such garish names as The Fiery Cross. You could even have Klan funerals, weddings and christenings.

It held mass family picnics attended by as many as 25,000 people and rapidly became one of the most important political organisations in the US. The Grand Wizard featured on the cover of Time magazine.

In 1925, an astounding 40,000 Klansmen and women paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue. At the time, the organisation boasted an eye-watering 4 million plus members. It seemed to have achieved the impossible: respectability.

KKK lobbyists helped bring in Prohibition, and also ushered dozens of politicians into power. Most significantly, lobbying by the organisation helped enable the passing of the 1924 Immigration Act, which created a quota system for the first time.

However, the supposedly devout organisation became drunk on power and was soon exposed as appallingly hypocritical. For instance, in 1925 the most famous Klan member in the country, the Grand Dragon of Indiana, David Stephenson, was convicted of raping and murdering his secretary. That hastened the demise of an organisation supposedly devoted to protecting “Protestant womanhood”.

By the end of the Second World War, the Klan had gone bankrupt, owing tax authorities $685,000. For the second time in its history, it disappeared. US society was changing dramatically, particularly as African-American servicemen were returning from war demanding to know why, after fighting racism and anti-Semitism in Europe, they were not being treated as full citizens in their own country.

That’s not to say that the racial ills of the US were instantly cured; far from it. Eighty years after the abolition of slavery, segregation still held sway in the Deep South. Black people still faced the same problems they had confronted in 1865. They were still excluded from all the things their white counterparts took for granted: well-paid employment and high-quality schools and hospitals. They were not even allowed to try on shoes in department stores. Mothers were obliged to take in a drawn outline of their child's foot in order to receive a new pair of shoes.

Bernard Lafayette, the civil rights activist, recalls: “My [Black] friend lived in Mississippi and his neighbour was white. Their dogs could play together, but their children could not.”

But things were changing, albeit very slowly. In 1954, the Supreme Court found that racial segregation in public schools was unlawful. This incensed white people in Southern states. At a demo outside a school admitting Black children for the first time, a white protester wielded a banner reading: “Keep our white schools white. KKK.”

The following year, Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat for a white passenger on a bus in Birmingham. Around the same time, Dr Martin Luther King launched his non-violent campaign for racial equality.

In 1963, 300,000 people marched on Washington demanding equal rights, and King delivered his celebrated “I have a dream” speech.

The demo radicalised white supremacists in the South. On 15 September 1963, two weeks after the rally in Washington, a bomb went off in the 16th Street Baptist Church in a Black neighbourhood of Birmingham. Four Black girls aged 11 to 14 were killed while practising their catechism.

The FBI immediately identified the four suspects, who were all members of the local KKK. The notorious head of the FBI, J Edgar Hoover, refused to send the file on to prosecutors, though. He believed that civil rights activists, whom he considered communists, posed a much greater danger to the US than white supremacists.

The former attorney general of Alabama, Bill Baxley, says at that moment “the Ku Klux Klan felt like they had a green light to commit violence. They could be as violent as they wanted and nothing would be done to them”. In the deep South, it became well-nigh impossible to convict guilty Klansmen, such as those responsible for the death of three civil rights activists in the notorious 1964 “Mississippi Burning” case.

After the heinous murder by KKK members of the white civil rights activist and mother of five Viola Liuzzo during the Selma to Montgomery march in 1965, president Lyndon Johnson designated the Klan “Public Enemy No 1”. Later that year, he signed the Voting Rights Act that enshrined the right of Black people to vote.

The bitter irony is that it was the Klan’s own dreadful crimes – which horrified even indifferent white people – that helped finally guarantee the success of the civil rights movement. By 1967, the KKK had lost 70 per cent of its members and its legal impunity had evaporated.

But you have to nail down the Klan’s coffin. The organisation has not died; in fact, it has seen a definite uptick in support since the election of Donald Trump as president in 2016. Throughout his presidency, he played on a fear of immigrants, which was very well-received by white supremacists.

The resurgence of the KKK is partly based on demographics. “Our census bureau has predicted that within 25 years, white people will become just one more minority,” says Mark Potek, an expert on the radical right. “It will sink to below 50 per cent of the population.

“This has driven this racial panic in this country. The idea is that white people will be just like brown people, Black people, another minority, that white people have been dispossessed, and that the country we white people built for our posterity and our white children is being stolen from us. That has culminated in the idea of a white genocide where white people are being killed or replaced.”

That noxious conspiracy came to a head at the “Unite the Right” protest in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017. Infuriated by the decision of Charlottesville City Council to take down Confederate monuments, thousands of far-right protesters converged on the city. Carrying burning torches – imagery all too familiar from the KKK – they chanted: “You will not replace us.”

That protest was capped by James Alex Fields Jr deliberately driving his car into a crowd of peaceful counterprotesters and killing activist Heather Heyer. In the aftermath, Trump claimed there were “very fine people on both sides”.

The KKK now intermingles with other far-right organisations and is being fired up by the Black Lives Matter movement, which started in response to the 2020 murder of George Floyd.

Last year, Harry Rogers, an avowed Ku Klux Klan leader in Virginia, was sentenced to three years to in prison after driving his pickup truck through a crowd of Black Lives Matter protesters in 2020 – and then bragging about it on his Facebook page.

The untrammelled fury contributed to the attempts by protestors to storm the Capitol in Washington DC on 6 January 2001. Their actions that day – which are still the subject of hundreds of court cases – led to a number of deaths.

It seems as if America has failed to cast out its old demons, then. The KKK has not gone away. Indeed, it has only been strengthened by modern technology. Korn-Brzoza says: “A century and a half ago, racists only had a few newspapers and flyers. Today it’s a dream for the racists. Now they have the internet that can reach millions of people. The movement has been reborn thanks to the internet.”

Veterans of the civil rights movement are not optimistic about the future. Dale Long, a prominent civil rights activist during the 1960s, says: “There’s a lot of work that has to be done in this country to make things better for all people. Sometimes I wish there was another Dr King.”

Adam Green, associate professor of history at the University of Chicago, agrees: “Laws were changed as a result of the civil rights movement. But we’re still having the fight in this country about whether the real America is a white America or the real America is a multicultural or plural America.”

The abiding message is that in the continuing struggle against the poisonous ideology of the KKK, we must never drop our guard.

Baxley concludes: “I think the story of the Ku Klux Klan is a part of the American story, but it’s a very disgraceful part.

“We must always be vigilant to try and stop it as soon as it rears its ugly head.”

The Ku Klux Klan: An American Story is available on Freeview Play

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments