Nasa is preparing for the first woman to walk on the Moon – it’s been a long time coming

In 2024, Nasa will be shooting for the Moon once more, but this time a woman will walk the lunar surface, writes Mick O’Hare

The United States is returning to the moon. Artemis 1, powered by Nasa’s Space Launch System (SLS), the biggest rocket ever built, made a successful uncrewed orbit of the moon in 2022 and returned to earth with nary a hitch. Artemis 2, the dress rehearsal for a moon landing, remains on course for 2024. And Artemis 3, scheduled for the following year, will return astronauts to the lunar surface, more than 50 years since a human last walked there.

The Apollo programme took 12 people – all of them white men – to the moon and back in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This time, when Artemis returns with a crew, a woman will walk on the moon, as will a person of colour. They might be the same person.

On 5 October 2022 Nicole Aunapu Mann became the first Native American woman in space when she started her five-month mission on the International Space Station (ISS). Mann, of the Wailaki people from what is today north-western California, said before she flew to the ISS that as a girl the thought of becoming an astronaut seemed impossible. “I was born in 1977 and in my mind, at that time, it was not in the realm of possibilities,” she said referring to her race and sex.

Mann joined the US Marine Corps after attending the US Naval Academy in Annapolis and flew combat aircraft in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2013 she was selected for Nasa’s astronaut training programme. She worked on the development of both SLS and the Orion capsule that SLS will carry to take humans to the moon, and following her return from the ISS she will be a contender for the lunar landings.

But Mann is up against stiff competition to become the first female moonwalker. Nasa has already announced the 18 initial members of the Artemis Team, the group of astronauts preparing for Nasa’s return to the moon. Nine of them are women and Mann is among them. They also include Christina Koch who took part in the first three all-female spacewalks, the experienced Anne McClain who has already completed 204 days in space, and former international rugby union player Jessica Watkins became the first African-American to serve on the ISS in April 2022.

“We do not yet know the identity of the first woman who will walk on the Moon,” says Emily Margolis, curator of American women’s history for both Washington DC’s Air and Space Museum and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Laboratory in Massachusetts. “But we do know that she will be incredibly skilled and accomplished. The women on the Artemis Team all hold advanced degrees in Stem fields and include shuttle astronauts, commercial crew commanders and decorated military pilots.”

It is fair to say that despite its achievements in space, Nasa – and by extension, the United States – has been markedly laboured in putting women into space. “Of course, women were no less interested or capable of flying in space,” says Margolis. “Nasa eventually accepted the first women into the astronaut corps in 1978, 20 years after the agency’s creation. Although Nasa did not explicitly prohibit women from applying for astronaut candidacy before then, the requirements implicitly excluded their participation. At the time, only military test pilots were eligible. And the military barred women from these careers. But astronaut eligibility requirements changed over time, as did society’s ideas about what careers were appropriate for women. And when Nasa opened a call for its first shuttle astronauts, the space agency explicitly recruited women for the first time.” That was in 1978.

Some commentators believed that Nasa was reluctant to put female astronauts into space because the backlash, should there be a catastrophic accident, might be greater if it involved a woman. Tragically, such a situation came to pass in 1986. The first American civilian, other than two Congressmen, to fly a space mission was schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe who perished in the Challenger space shuttle disaster. The shuttle exploded when one of its external solid rocket boosters failed 73 seconds after launch.

Her death, more than perhaps those of her fellow astronauts – all military professionals – had a huge impact on the American public. But Margolis says that it was more the fact that McAuliffe was a teacher and a civilian than her sex. “Judy Resnik, a professional astronaut, also lost her life in the accident,” she points out. “The reason Christa’s death had such an impact was because she was going to be America’s first teacher in space. Her journey was highly anticipated. Many teachers and students watched the launch on live television because it fell during a school day. That was the shock.”

McAuliffe’s death resulted in the cancellation of Nasa’s Civilians in Space programme. “Nasa deemed the risk for civilians too great to continue,” says Margolis. “The death of the crew shocked a nation that had always returned its astronauts safely to Earth. The space shuttle was publicly understood to be a safe and comfortable ride to orbit. But Challenger was a tragic reminder of the dangers.”

“McAuliffe’s death is particularly painful,” wrote New Scientist magazine. “Astronauts are the targets onto which many ordinary folks imprint their ideals. That one should be a smiling, New Hampshire schoolteacher means Nasa will be under immense pressure to protect those it chooses to send into space. It may choose never to send a civilian again.” It chose the opposite, but the soul-searching was punishing.

The first American woman in space was Sally Ride who, ironically, flew into orbit on the same space shuttle Challenger, three years prior to the disaster, on 18 June 1983. Ride had responded to a newspaper request which explained Nasa was looking for new astronauts and wanted women to apply. Her successful return rather put paid to questions asked before her flight which included the rather direct: “Will the flight affect your reproductive organs?” – something Alan Shepard, the first American man in space, was almost certainly never asked – and the rather ludicrous: “Do you cry when things go wrong at work?” She also declined to take a make-up bag. On a more positive note, her flight did lead to the feminist slogan “Ride, Sally Ride” emblazoned on T-shirts across the US and beyond.

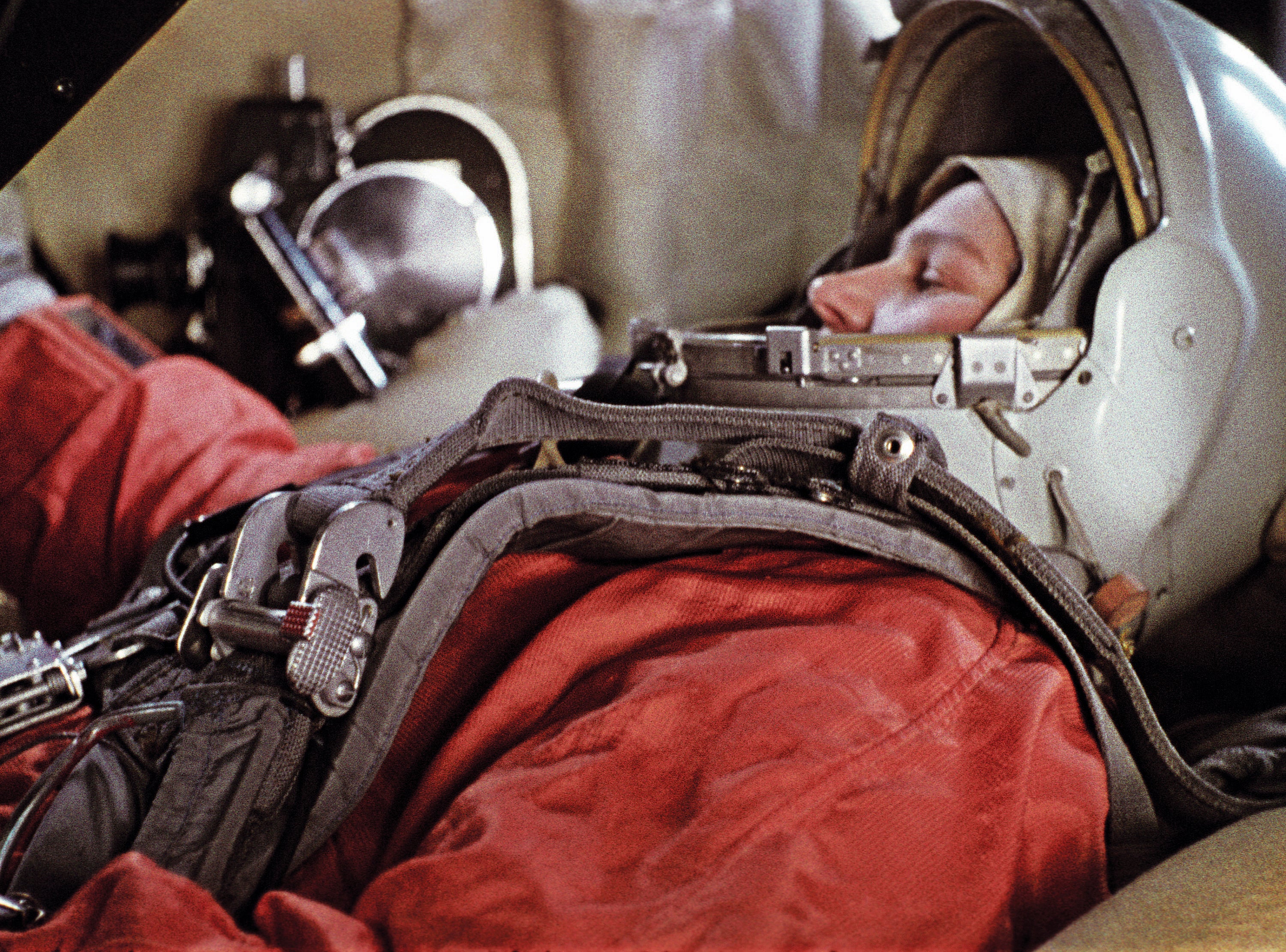

Although Sally Ride was the first American female to fly into space, she was the third woman overall. Two decades before Ride launched from Florida’s Kennedy Space Centre, Valentina Tereshkova, a lieutenant in the Soviet Air Force, was carried into orbit aboard Vostok 6, becoming the first woman to fly in space. Her trip took place on 16 June 1963, only two years after the first man, Yuri Gagarin, achieved the same.

And although Tereshkova was hailed at the time as a feminist icon – and remains one to this day – her flight, perhaps unsurprisingly, did not lead to the emancipation of spaceflight many hoped it might. Quite astonishingly, she remains the only woman to have ever flown a spacecraft solo, and still the youngest woman to fly in space.

It was indeed a different era. News agency United Press International wrote, under the headline “First Girl in Space Gets a Rousing Welcome from Communist Women”, that “the ladies showed their approval at the four-day meeting which has the announced aim of forwarding women’s rights, peace and disarmament.” It added: “Soviet propaganda media are using Miss Tereshkova as evidence of the opportunities for woman in a communist system compared to the West where, Soviet authorities maintain, millions of women are downtrodden.”

The report is, in equal measure, patronising and sceptical. The scepticism was probably not misplaced. It went on to say that Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev “interrupted a triumphal speech to steal a kiss from Miss Tereshkova.”

After Tereshkova flew it would be 19 years before another woman would fly in space — Soviet cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya in 1982 — one year before Ride. The Soviet commitment to equality espoused by the acclaimed launch of Tereshkova was always something of a sham. Once Khrushchev had seen the headline – and stolen the kiss – the patriarchy reverted to type.

The Soviet Union had, in all truth, no intention of putting woman into space. But when, in 1961, Nikolai Kamanin, the director of cosmonaut training, heard that the US had been considering it, he deemed it would be “an insult to the patriotic feelings of Soviet women.” Kamanin’s information was erroneous. The US had no plans to put a woman in space. However, totally separate from Nasa, 13 American women were undergoing psychological evaluation for spaceflight as part of physician William Randolph Lovelace’s privately run “Women in Space” programme. This may have been the source of Kamanin’s inaccurate intelligence.

Whatever the reason, he acted. By January 1962, 400 candidates had been selected, all of them parachutists. A month later that had been whittled down to five. By then all of them knew that only one of them would ever fly in space, the others would be retired. It would become clear that they were merely part of a propaganda stunt.

Tereshkova’s closest rival for the flight, Valentina Ponomaryova, had finally been ruled out when, in interviews, it became clear she had strong feminist opinions rather than relying on the Soviet-era political platitudes she was expected to espouse. The Soviet space programme’s professed egalitarianism was always a veneer.

Helen Sharman, the first Briton in space who flew to the Soviet Union’s Mir space station in 1991, says “It was all about racing the US for firsts: first spacecraft to orbit the Earth, first person in space – at that time it was always going to be a man – first woman in space, first spacewalker, and so on. Although women in the Soviet Union routinely were engineers, doctors and farmers, it was still a patriarchal society. Traditional values that framed women first and foremost as mothers and home makers endured.”

Kamanin condescendingly referred to the woman cosmonauts as “Gagarins in skirts”. To him, putting a woman in space was merely a means to an end. Kamanin may also have been the source of rumours that, during Tereshkova’s flight, she became too ill to carry out any of her functions and this was subsequently used as the excuse for not sending more female cosmonauts into space. Tereshkova has always denied this and historians now accept that it was untrue.

Yet despite this disappointing hinterland to her flight, Tereshkova’s achievement was a remarkable one. Even if political machinations were at play, the accomplishment dwarfs the motivation. She might have been an inadvertent puppet of the Soviet bureaucratic machine but she had to study, train and fly simulations to the same level as every male cosmonaut – many of whom failed to make the grade – and at a time when safety was neither paramount nor guaranteed.

Indeed, one story suggests that had it not been for her keen eye and an understanding of the spacecraft in which she was being carried, she might have been the first woman to die in space. Soon after take-off she realised that the capsule’s systems for re-entry had been mis-set by the ground engineers. She argued with mission control until they realised she was correct and sent her new settings with her mission having to be extended. They also swore her to secrecy. Tereshkova has always assumed that none of the all-male ground crew wanted it to be known that a woman had spotted their error.

She was awarded the Order of Lenin and became a Hero of the Soviet Union. She remained a committed member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991 and was a staunch opponent of the reforms of the last Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev which led to the break up of the nation that had put her into space. “I don’t want to hear his name,” she often tells interviewers today who ask for her opinion. “The Soviet Union made mistakes, but it is wrong to dismiss its achievements. For a lot of people, it was a great nation.”

Her residual Soviet patriotism may have informed her future political direction. In recent years, she has somewhat tarnished her reputation – in western eyes at least – by being a supporter of Russia’s authoritarian leader Vladimir Putin, standing as a candidate for the United Russia party and winning a seat in the Duma. Aged 85, she still cuts an austere figure, often unsmiling, seemingly as driven as the day she stepped into Vostok 6 six decades ago.

“When I trained in Star City north of Moscow I was always in awe of the early cosmonauts, especially Valentina,” says Sharman. “But I got to know her and she made a point of coming to the breakfast reception send-off for my crew and me, before we left for our launch in Kazakhstan. She always wanted to show support for women space fliers. We still come across each other at various events around the world – Covid and the Ukraine war excepted. Valentina always makes sure to gather all the female astronauts for a photo.”

And now the US has the opportunity to find the modern-day successor to Tereshkova. The first woman to walk on the moon will be lauded as fervently as the first woman to fly in space, much as Neil Armstrong – the first man to walk on the moon – and Gagarin are extolled today. Margolis explains that the selection procedure will be thorough but “is the purview of Nasa’s Astronaut Office. Nasa does not usually comment on this process.” It seems we will have to just wait and see who emerges.

Sharman looks forward to that day and the day a woman walks on the moon, but thinks Tereshkova’s equivalent achievement, despite its primacy, is sometimes lost in the propaganda battles fought between the spacefaring nations. “Nasa’s press and PR machine is good at ensuring we don’t forget Sally Ride and that we are aware when two American women are making space walks together, for instance,” she notes “And British politics leans more to the US than to Russia, which filters down to education and a culture that embraces American achievements over those of Russia.” She feels that Tereshkova’s feat is sometimes underplayed today.

But with the hindsight of history and the 60 years of struggle for emancipation that women have fought since, Valentina Tereshkova, whatever the propaganda reasons behind her flight, proved – if proof were needed – that women are equal to men. Her flight in Vostok 6 was as successful and consummate as those of her male compatriots. She set a benchmark – to date 75 women have flown in space – and remains a feminist role model. Soon a woman will walk on the moon. And the fame that was once conferred on Tereshkova will then be transferred onto her shoulders. Those are big boots to fill.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments