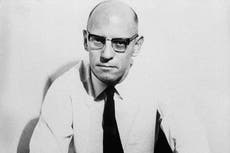

Peter Singer: The most controversial philosopher alive today

Singer’s views on subjects such as abortion, animal rights and euthanasia have got him into hot water

There is a thought about philosophy that it has no relevance for everyday life; that philosophers spend their time in ivory towers pondering questions that have no answers, and that nobody cares about anyway.

Peter Singer, perhaps the most controversial philosopher alive today, is living proof that this is at best an oversimplification. His most trenchant critics have suggested – entirely falsely – that he is a kind of Nazi; his appointment as Professor of Bioethics at Princeton was strongly criticised; and in Germany, his lectures have been disrupted by protests. The cause of this controversy are his ideas about subjects such as abortion, animal rights and euthanasia.

Singer’s ethical views are consequentialist, which means that he thinks that it is outcomes that are important in judging whether an action is right or not. More precisely, he thinks that what is significant is whether an action tends to maximise the satisfaction of preferences; in other words, does it increase the ability of beings to satisfy the preferences that they have (for example, a desire for material wellbeing or cultural enrichment). At first thought, this conception seems unproblematic; however, further reflection shows that it is in fact fraught with difficulties.

Consider, for example, the ethical issues surrounding the question of how we should treat (non-human) animals. In his book Animal Liberation, Singer argues that the fact that humans and animals belong to different species is not in and of itself a justification for treating them differently (to think otherwise is to be guilty of speciesism). In ethical terms, what counts is whether beings have the sorts of lives that are worth living, and part of what is involved here has to do with whether they have, or might come to have, preferences at all (which could be rooted in a sense of self, attachment to others, plans for the future, and so on).

This leads us into tricky ethical territory. For example, is it right to sacrifice the life of a great ape in order to save the life of a human being in a persistent vegetative state? Singer’s position seems to require that we allow the human to die – a person in a persistent vegetative state just does not have the sort of life which justifies killing a great ape.

This kind of argument can also be used to shed light on other ethical dilemmas. Take euthanasia, for example: if a baby has massive brain damage, then it isn't clear that taking the baby's life will always be wrong. The infant will have no real sense of self, no attachments to other people, no sense of the future, no psychological investment in its own survival, and likely only suffering and misery to look forward to in its future. In these kinds of circumstances, Singer’s consequentialism suggests that the right thing to do is to end the baby’s life as painlessly as possible (assuming we have parental consent).

It is now easy to see how Singer’s views have got him into hot water. The trouble is, though, it isn’t obvious where his arguments go wrong. It might just be that philosophy sometimes leads us to uncomfortable conclusions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks