Michel Foucault: A critic of social institutions

More than just a philosopher, Michel Foucault’s pervading theme is that human relations are defined by the struggle for power

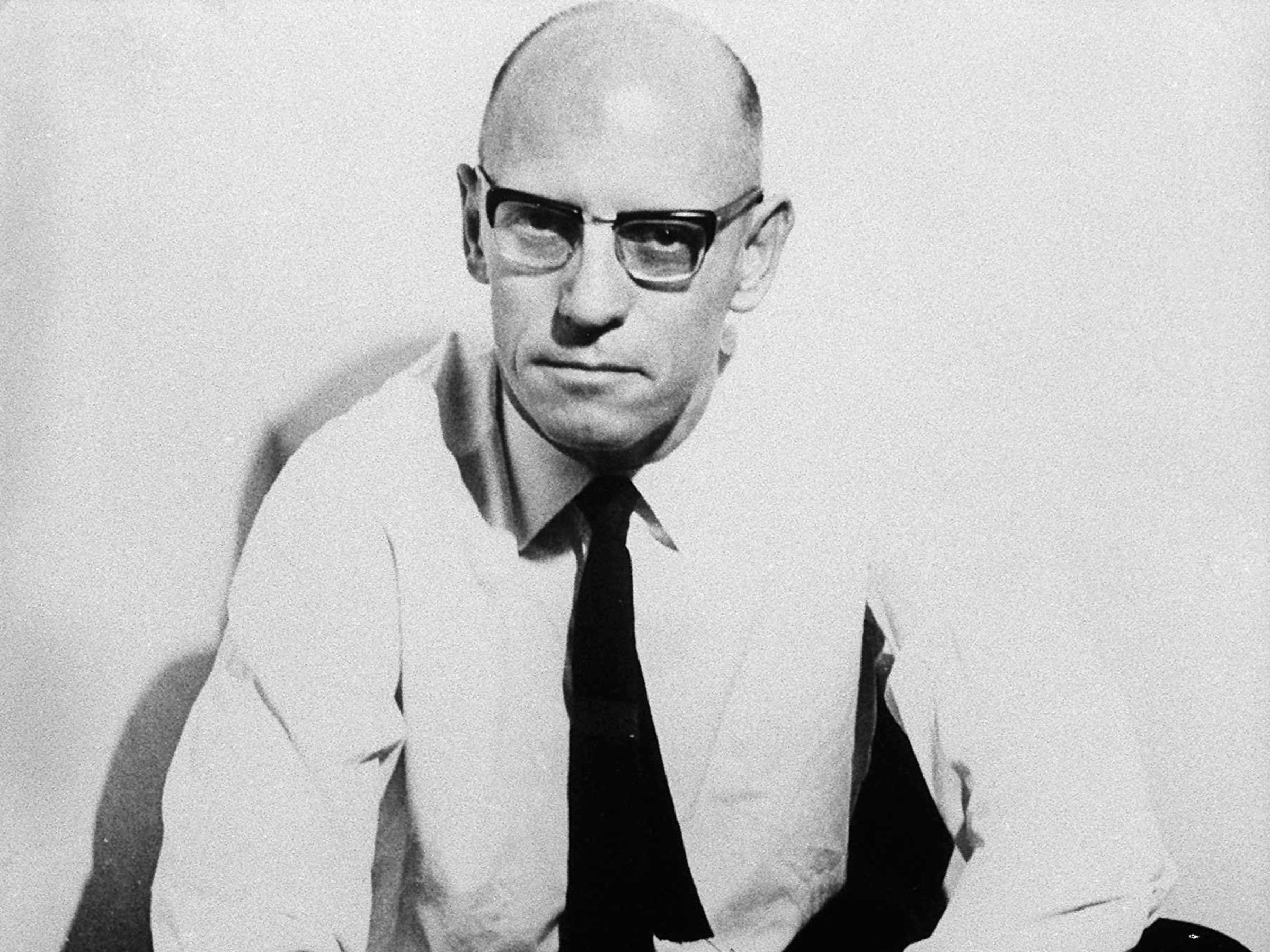

Michel Foucault’s (1926–84) influence extends beyond philosophy across the humanities and social science. He is perhaps best known for his critiques of various social institutions, most notably psychiatry, medicine and the prison system.

The British philosopher Ted Honderich once said of late 20th-century French philosophy that “it aspires to the condition of literature or the condition of art”; that one thinks of it as “picking up an idea and running with it, possibly into a nearby brick wall or over a local cliff, or something like that”. It is very easy to find examples of the kind of thing that Honderich is talking about. Here’s Jacques Derrida defining the word “sign” in Of Grammatology: “… the sign is that ill-named thing, the only one, that escapes the instituting question of philosophy: ‘what is …?’”

Yes, the crossings out are deliberate. The idea is that the erased words are inadequate to express their intended meaning, but that there aren’t any better words either. So they are put “under erasure”. David Lehman, in his book about deconstruction, Signs of the Times, says of this technique that it very quickly becomes an annoying affectation. Many people will agree with him.

Happily, not all modern French philosophy is quite so esoteric. The work of Michel Foucault is a case in point. It is true that in comparison with Paine and Mill, for example, Foucault is a difficult philosopher. However, he is no more difficult to understand than Kierkegaard, and he is considerably easier to get to grips with than Hegel. His work also has the merit that it has original and interesting things to say about power, knowledge and subjectivity.

Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in Poitiers, France, the second child of Anne Malapert and Paul Foucault, a prominent local surgeon and professor of anatomy. His father hoped and expected that his son too would choose to “become a doctor”. However, it seems that Foucault’s family were not the formative influence that they might have been. Rather, in an interview, Foucault suggested that his future ambitions were most profoundly affected by his experience of the Second World War; thus, in 1946, he entered the École Normale Supérieure, graduating in 1951 with degrees in philosophy and psychology. He then went abroad for several years – according to some commentators, in order to escape the conservative sexual mores of French culture – taking up teaching jobs in Sweden, Poland and Germany, before returning to France in 1960 to join the philosophy department at the University of Clermont-Ferrand.

This marked the beginning of the period which established Foucault’s intellectual reputation. In 1961, he published his first major work, Madness and Civilisation; and he followed this up with eight further books written over a 20-year period, which included The Order of Things, The Archaeology of Knowledge, Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality.

Power and the self

These works show Foucault mapping out a new course for French philosophy in the latter part of the 20th century. He drew upon the disciplines of philosophy, history, psychology and sociology in an attempt to show how power and knowledge interact to produce the human subject, or, the self. His intention was to demonstrate that human beings are constituted as knowing, knowable and self-knowing subjects in relations of power and discourse, which necessitated rethinking the concept of power, and analysing the links between power and knowledge.

The general process of the objectification of the human subject is linked to historical changes in the nature of power, and to corresponding developments in the areas of human and scientific knowledge

Foucault claims modern western societies are characterised by three modes of objectification which function to constitute human beings as subjects. These modes are: “dividing practices”; “scientific classification”; and “subjectification”.

Dividing practices objectify people by distinguishing and separating them from their fellows on the basis of distinctions, such as normal and abnormal, sane and insane, the permitted and the forbidden. It is by means of dividing practices that people are categorised, for instance, as madmen, prisoners and mental patients. These categories provide human subjects with the identities through which they will recognise themselves and be recognised by others. Thus, in Madness and Civilisation, Foucault analysed the mechanisms by which madness was established as a specific category of human behaviour, one which legitimised the detention of individuals in institutions.

The mode of scientific classification objectifies by means of the discourses and practices of the human and social sciences. For instance, it is possible to break down mental illness into the numerous categories of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; in Birth of the Clinic, Foucault showed how the emergence of the human sciences in the 19th century led to the human body being treated as an “object” to be analysed, labelled and cured, something which is still characteristic of modern medicine today.

Subjectification is slightly different from the first two modes of objectification in that it refers to the way in which people actively constitute themselves as subjects. This idea runs through Foucault’s History of Sexuality, where he analyses how the desire to understand oneself leads to our confessing our most personal thoughts, feelings and desires both to ourselves and to others. This necessarily implicates us in networks of power relations with authority figures – for example, doctors, psychiatrists and, in the 21st century, perhaps even TV producers – who maintain that they can understand our confessions and reveal the truth of them. It was Foucault’s contention that through the expansion of this process of confession, people become objects of their own knowledge and of other people’s knowledge; objects, moreover, who have learned how to reconstitute and change themselves. He argued that this phenomenon is a central part of the expansion of the technologies for the control and discipline of bodies and populations in modern societies.

The general process of the objectification of the human subject is linked to historical changes in the nature of power, and to corresponding developments in the areas of human and scientific knowledge. Foucault used the expression “power/knowledge” to denote this conjunction of power and knowledge. Instead of focusing on coercion, repression and prohibition, he showed how power produces human subjects and the knowledge that we have of them. This idea has its fullest expression in the notion of “bio-power”.

Foucault noted that in the course of the 17th century, state power began to make its presence felt in all parts of a person’s life; then, with the emergence of industrial capitalism, there was a move away from the use of physical force as a kind of negative power towards new, more effective, technologies of power, which were productive and aimed to foster human life. The state started to focus on the growth and health of its population. Foucault argued that a new regime of bio-power had become dominant, which aimed at the management and administration of the human species or population, and the control or “discipline” of the human body.

State power and state control

In Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault showed how Jeremy Bentham’s idea of the panopticon, a type of prison, was a paradigmatic example of disciplinary technology. The panopticon is built in such a way that it functions effectively whether or not prison guards are actually present. Prisoners have no way of knowing whether they are being watched, and so they must behave as if surveillance were constant and never ending. Effectively, then, prisoners become their own guardians. Thus, according to Foucault, the panopticon brings together power, knowledge, the control of the body and the control of space into a single, integrated disciplinary technology. The parallels here with wider society are clear. Society exerts its greatest power to the extent that it produces individual human subjects who police themselves in terms of the discourses and practices of sexual, moral, physical and psychological normality.

Foucault’s concern with matters to do with power and the control of populations and bodies was mirrored in his political activities; he was, throughout his adult life, interested in issues to do with gay rights, prison reform, mental health and the welfare of refugees. However, there is something slightly paradoxical in this, for it is one of the criticisms of Foucault’s work that it functions to undermine any commitment to emancipatory politics. Put simply, the thought here is that by elevating power to the point where it infects everything, Foucault’s position rules out the possibility of any genuinely benevolent, or even rational, impulse or intervention. For example, if scientific psychiatry has transformed the lives of “schizophrenics” through the use of antipsychotic drugs, it is only because it is aimed towards the control of patients, not because it seeks good outcomes for them. Or, to take slightly different example, if truth about history is a function of power, then whether or not the Holocaust took place is not a matter of historical fact, but rather a matter of establishing, or not establishing, the dominance of particular historical narratives.

Many of Foucault’s critics claim that his views lead straight to a relativism about both truth and morals. For example, Patrick West argued in The New Statesman:

“The pervading theme in Foucault’s philosophy is that human relations are defined by the struggle for power. Right and wrong, truth and falsehood, are illusions. They are the creation of language and the will to dominate … Thus, there is no such thing as benevolence: men have created hospitals, schools and prisons not to cure, educate and reform, but to control and dominate ‘the Other’. The rationalism of the Enlightenment was merely a mask for this malevolent impulse.”

There is certainly something right about this criticism. Indeed, the influence of thinkers like Foucault has been declining in recent years precisely because it has been recognised that their nihilist leanings undermine the possibility of genuine political commitment. Nevertheless, even if one wishes to reject the more radical aspects of Foucault’s approach, it would be wrong to dismiss his work in its entirety. Foucault’s importance is that he showed how power can operate; that is, to create human bodies, human subjects and populations which in various ways are surveyed, categorised, disciplined and controlled.

Foucault lived his life as if he were driven by the need to transcend both physical and cultural limits. He experimented with LSD, visited sadomasochistic clubs in California, attempted more than once to kill himself, and talked of the intense pleasure he had experienced after being hit by a car. In the end, he was killed by an AIDS-related illness; he was one of the first victims of a disease he presumably thought only properly existed in the context of particular discourses or narratives.

Major works

Madness and Civilisation (1961)

An analysis of the genesis of modern psychology, it attacks the idea that “madness” and “mental illness” are natural categories, suggesting instead that they exist at the intersection of various institutional, social and political imperatives.

Birth of the Clinic (1963)

This work, the first of Foucault’s archaeological studies, shows how the emergence of the human sciences, and medical science, in particular, led to the human body being treated as an “object” to be analysed, labelled and cured.

The Order of Things (1966)

A complex analysis of the “epistemes” – the systems of thought and knowledge – which, across time, have underpinned various kinds of social scientific enquiry. It pursues the claim that different ages have a different understanding of the relations between language and truth.

The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969)

A theoretical articulation of the archaeological method which had underpinned his previous historical studies. A difficult book, it introduces the new concept of a discursive formation, which “presents the principle of articulation between a series of discursive events and other series of events, transformations, mutations, and processes”.

Discipline and Punish (1975)

A study of the emergence of the modern prison, and, more generally, a disciplinary technology which functions to classify and control human subjects.

The History of Sexuality (3 volumes, 1976, 1984, 1984)

These three volumes represent the beginnings of a study on human sexuality, which Foucault never completed. The most mature expression of Foucault’s thoughts about biopower and biopolitics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments