Simone de Beauvoir and the ‘other’ woman

‘The Second Sex’, as well as being a feminist manifesto, implored women to challenge ingrained notions of inferiority to the men who dominated them

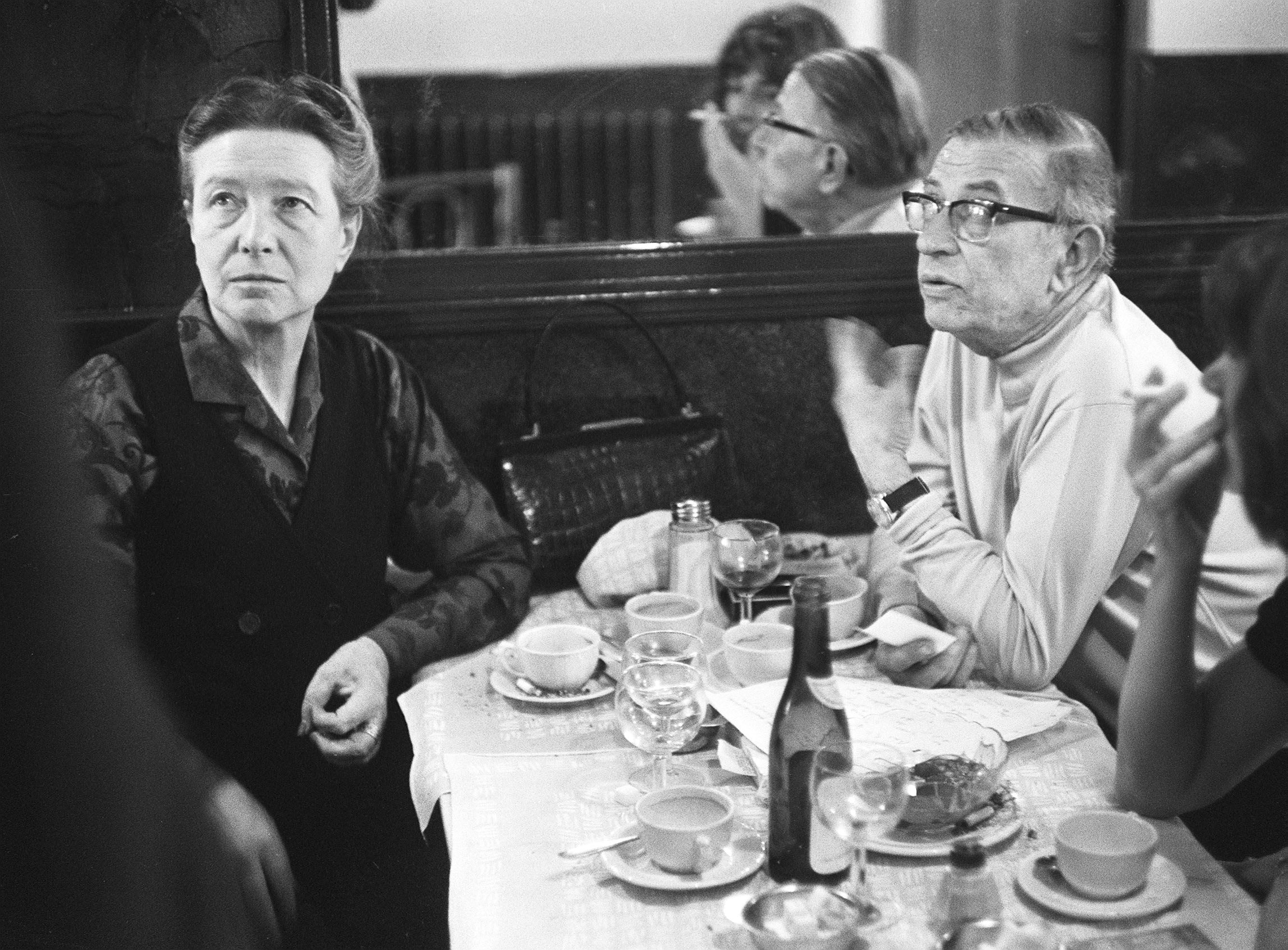

The reputation of the French existentialist and feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir (1908–86) has a certain irony attached to it. The major claim of her most important book, The Second Sex, arguably the most significant feminist text of the 20th century, is that women tend to be conceived as “the Other” of men.

Certainly, this is true in the case of Beauvoir, since quite unjustifiably she is remembered today as much for her relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre, as she is for her own original philosophy.

The notion of “the Other” might sound commonsensical, but in fact it is based on a complex piece of existential analysis. Its roots lie in Hegel’s famous dialectic of the “Master and the Slave”. In simple terms, Hegel argued that people come to see themselves as autonomous agents by dominating other people (the Other). Inspired by Sartre’s arguments in Being and Nothingness, Beauvoir used this idea to understand the relations between men and women. Thus, in the introduction to The Second Sex, she claimed that woman “is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is the incidental, the inessential, as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute – she is ‘the Other’.”

There are two additional Hegelian terms that Beauvoir makes use of in order to understand the relationship between the sexes: transcendence and immanence. Men exhibit their transcendence by choosing to take on projects, normally within their working lives, which define their relationship with the world. Women, in contrast, are confined to a domain that is characterised by immanence: they are condemned to repeat the passive and mundane tasks of everyday existence – in particular, those associated with their roles as mothers, housewives and the recipients of male libidinal desire.

However, this does not mean that women lack freedom. Beauvoir’s existentialism means that she is committed to the view that every person is necessarily free. Rather, her argument is that women are thought of as, and think themselves to be, innately inferior to men – their status as the other is perceived to be coterminous with their womanhood. To put this another way, a belief in the inferiority of women is enmeshed with the idea of “the eternal feminine”. To be a woman is in part to be man’s other.

Because female inferiority seems to be natural, just a part of what it is to be a woman, women are often implicated in their own subjugation. There is a link here with a central theme of existentialist philosophy – that there are certain advantages associated with the denial of freedom. Perhaps, then, Beauvoir suggests, some women just prefer the security of a life defined in terms of their relationships with particular men.

It is Beauvoir’s view, of course, that the idea of the “eternal feminine” is a myth. As she famously puts it in The Second Sex: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” In order to achieve freedom, “women must cast aside those illusions of womanhood that confine them to lives of endless repetition, passivity and drudgery”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments