Jean-Paul Sartre, defining existentialism and nothingness

A consummate philosopher of freedom, Sartre explored the primacy of individual existence and the lack of objective values

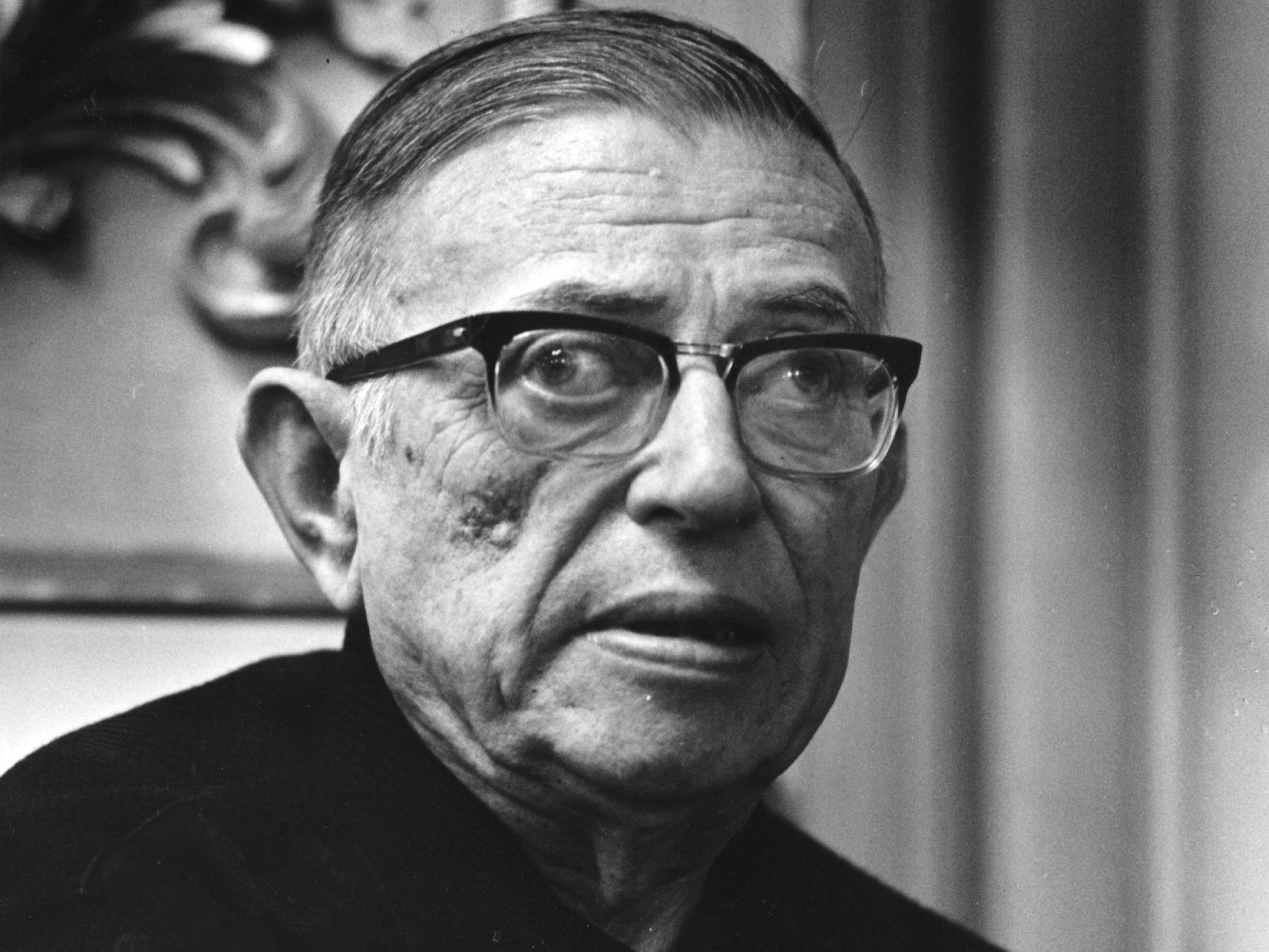

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80) is the philosopher whose work – certainly in the English-speaking world – came largely to define the existentialist movement in the 20th century.

The image of the existentialist as a cafe-dwelling, chain-smoking, beret-wearing intellectual type comes largely from Sartre. And the themes he explored in his writings – particularly the primacy of individual existence, human freedom and the lack of objective values – are precisely those of existentialism.

Sartre was born into a comfortable, middle-class existence. However, his childhood was far from happy. He was brought up in the home of his maternal grandfather, Karl Schweitzer – a strict and domineering man – his father having died when he was just a year old. He was an unattractive child, short in stature and the victim of an eye condition that made it appear as if his gaze were permanently askance. He had few childhood friends, and spent most of his early life reading and writing in his grandfather’s library. There was also a strange dynamic between Sartre and his mother; until his grandfather eventually put an end to it, she pampered him, dressed him in ornate clothing and let his hair grow long.

However, whatever his childhood difficulties, it was clear from very early on that Sartre was extremely smart. Or as he put it, he was a child prodigy. Of course, we now know that the prodigy grew up to be one of the most celebrated intellectuals of the twentieth century. Sartre is perhaps unique in the breadth of his accomplishments. As well as being a considerable philosopher, he was also a top-flight novelist, playwright and biographer. Indeed, in 1964 he was offered the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he declined saying that he didn’t want to be “transformed into an institution”.

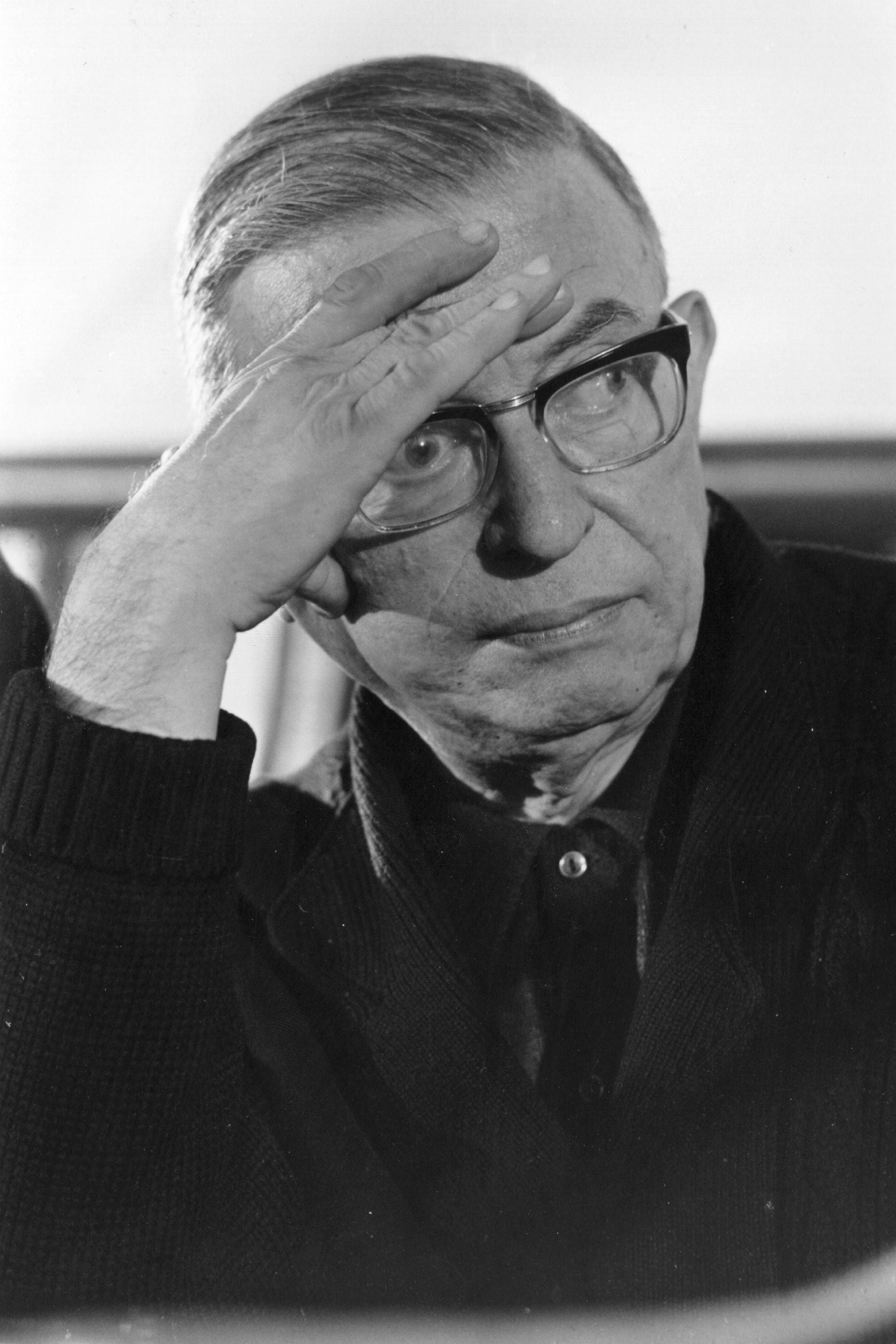

Being and nothingness

In the case of Sartre, there is something paradoxical in wondering whether his childhood explains the kind of life he lived as an adult, because Sartre is the consummate philosopher of freedom. He did not think, at least not in any uncomplicated way, that people are condemned to live certain kinds of lives by the events which occur in their past. Indeed, it is a common view about Sartre that he is a kind of radical humanist, concerned with the requirement which individuals face to choose their own lives and the morals that they espouse. However, although there is something right about this view, the truth about Sartre’s philosophy is more strange than might at first be supposed.

We exist first; the self that we subsequently become is a construct that is built and rebuilt out of experiences and behaviour. In principle, then, the self is something which can be changed

Some of this strangeness derives from the way that he conceptualised consciousness and the human subject. In Being and Nothingness (1943), his major existential work, Sartre divided being into two primary realms: being for-itself, which is consciousness; and being in-itself, which is everything else. He argued that the for-itself is characterised by nothingness – that is, emptiness lies right at the heart of being. What did he mean by this? In simple terms, he meant that there is no human essence. Consciousness is permanently detached from the given order of things. It is pure, empty possibility, and therein lies its freedom.

This is a complicated idea. Some light can be shed on it by considering Sartre’s treatment of the concept of negation. This concerns the capacity to conceive of what is not the case. It is manifest in a whole series of attitudes that the for-itself can adopt towards the objects to which it is directed. Perhaps most significant is the ability of the for-itself to project beyond the given present to an open future of unrealised possibilities – to imagine what might be the case. In this sense, the freedom of the for-itself is the permanent possibility that things might be other than they are. Human beings do not find this freedom easy to live with. With the realisation that the future is always radically in doubt comes anguish. Sartre argued that in order to escape anguish individuals adopt strategies of bad faith, that is, they seek to deny the freedom that is inevitably theirs.

Bad faith

There are a couple of very famous examples which illustrate this point. Sartre asked us to imagine a liaison between a woman and a man who she knows wants to seduce her. He takes her hand, but rather than facing up to the requirement to accept or reject him, the woman pretends not to notice; she leaves her hand there as if she were just a passive object. In this way, by, as it were, denying her own subjectivity, she avoids the obligation to choose. The second example involves an over-zealous cafe waiter who plays his role with just a bit too much care. Sartre’s idea here is that the waiter is attempting to subsume himself within his role; to make it as if everything he says and does is determined by his “waiterhood”. Of course, for Sartre the reality is quite different. The man chose to be a waiter, and at every instance he makes the choice again, because no person has the kind of identity that the waiter seeks in his waiterhood.

A kind of bad faith can also enter into the way that people think about matters of morality. For example, individuals can attempt to flee the freedom which is theirs by adopting an attitude of seriousness towards a perceived moral sphere. That is, they might portray their actions as entirely governed by a binding moral code: “I’d like to help you, but I can’t, it would be wrong.” Of course, as far as Sartre is concerned, this is just so much rationalisation. In his popular Existentialism and Humanism, he considers the case of a young man who is confused about whether or not to join the French Free Forces to fight the Germans or whether to stay at home to look after his mother. He shows that it is very difficult to see that there are any clear guides to action in such a situation.

Christian ethics, for example, doesn’t offer any way of deciding between the general aim of fighting for the whole community and the precise aim of helping one particular person to live. Sartre concludes that all that it is possible to say is that the moral choices that individuals make are theirs and theirs alone, and they are fully responsible for them. All people can do is to choose authentically in the full recognition that they choose freely.

However, the fact that the for-itself is always and inevitably free does not mean that individuals make their choices in a vacuum. Rather, they face up to the specifics of the situations that they confront – for example, that the thief is carrying a knife – and the facticity of their particular lives. Facticity here refers to all the things about an individual that cannot be changed at any given point in time – for example, their age, sex and genetic dispositions. Choices then are made against a particular background, so freedom of consciousness does not translate into the idea that people are free to do absolutely anything at the drop of a hat.

Human freedom and the self

Interesting in this regard is the role of the self and its relation to human freedom (the self was first properly discussed in an early work, The Transcendence of the Ego). Sartre denied that individuals have essential selves. Indeed, part of what defines his philosophy as existentialist is his claim that existence precedes essence. We exist first; the self that we subsequently become is a construct that is built and rebuilt out of experiences and behaviour. In principle, then, the self is something that can be changed, it can be reconstructed. However, in practice, it is not easy to choose a course of action that is out of character with the fundamental project of the self. Consequently, the self that we have become imposes another limit on the practice of the freedom that belongs inevitably to the for-itself.

In this treatment of Sartre’s ideas, we have concentrated on the philosophical foundations of his idea of freedom. As a result, his philosophy comes out looking as though it is almost entirely concerned with the individual. This is something of a distortion. It would have been possible to have entered Sartre’s work at a different point – for example, with his later book, Critique of Dialectical Reason – and to have painted a different kind of picture. His commitment to leftist politics, his interest in the dynamics of social groups, and the fact that he lived at a time of massive political and social upheaval meant that he was almost bound to move beyond the concerns of his early work. Indeed, by the 1960s, with the popularity of structuralism and the emergence of post-structuralism and postmodernism in continental Europe, Sartre’s earlier existentialist philosophy had largely fallen into disrepute.

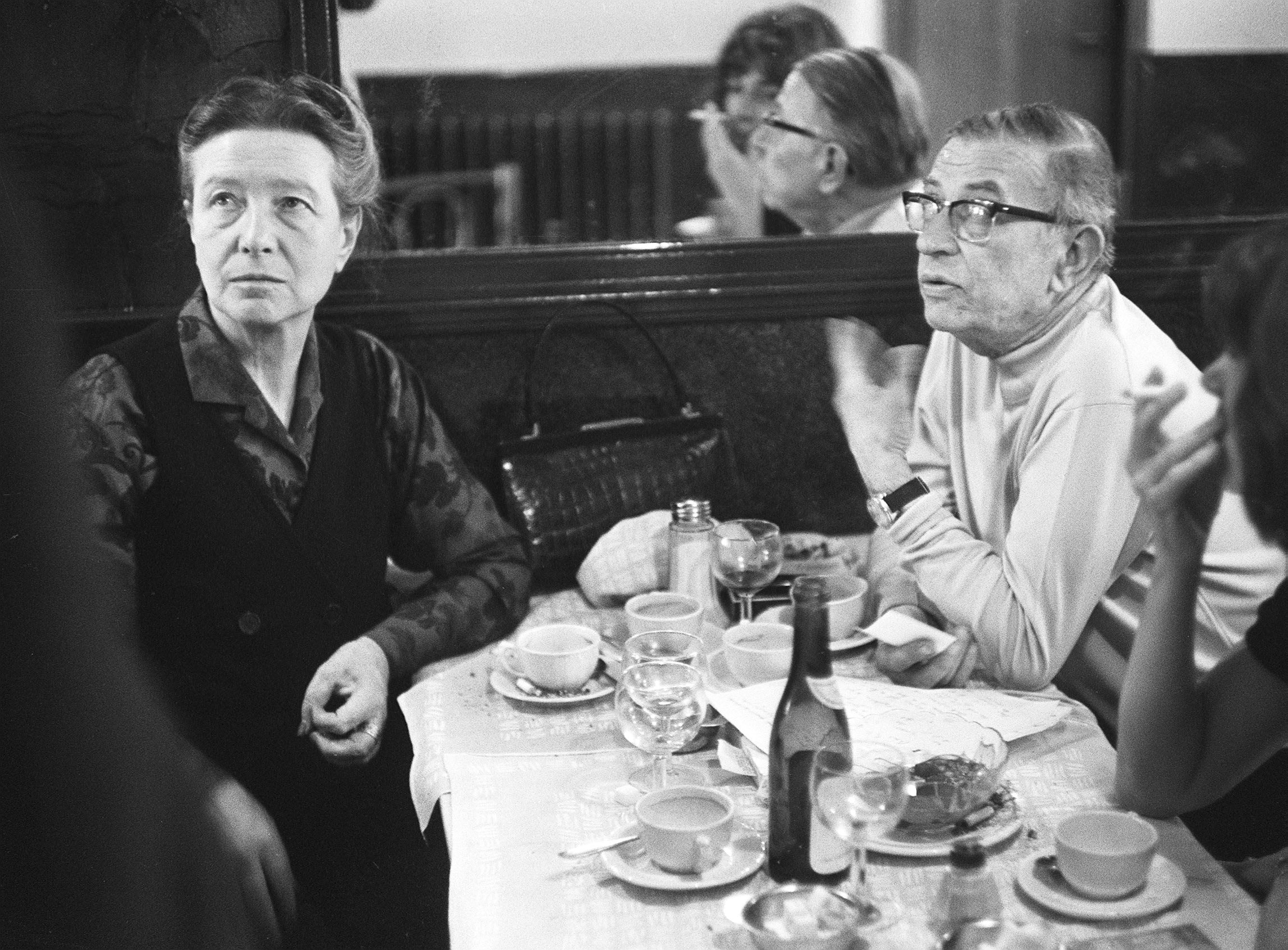

However, fashion in intellectual circles is never constant, and there has been something of a revival of interest in Sartre’s work. Certainly, Sartre remained close to the heart of the French people right up until his death in 1980. His funeral in Paris was attended by more than 20,000 people, and the crowds were so dense that his long-term partner Simone de Beauvoir was almost mobbed as she arrived at the cemetery. Years later, people are still visiting his grave, now shared with de Beauvoir, to pay their respects.

Major works

The Transcendence of the Ego (1936)

This work develops a phenomenological account of the ego, which is specified as a construct rather than the indivisible source of a person’s behaviour and character.

Nausea (1938)

Perhaps Sartre’s major existentialist novel, in which he explores the philosophical implications of the contingency of existence through the experiences, charted in a diary, of its main character, Antoine Roquentin.

Sketch for a Theory of Emotions (1939)

In contrast to the traditional view, which sees emotions as largely unchosen, this work articulates the view that they are actively constructed in order to transform our experience of the world.

Being and Nothingness (1943)

Sartre’s major work is primarily given over to an analysis of being-for-itself (or consciousness). It features groundbreaking discussion of anguish, bad faith, the spirit of seriousness, being-for-others, and other central elements of existentialism.

Existentialism and Humanism (1948)

Popular work in which Sartre defends existentialism against some of the criticisms which had been levelled against it. Features discussions of ‘abandonment’ and the absence of an objective moral sphere.

Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960)

A Marxist makeover of existentialism. It represents a retreat from the existentialist emphasis on radical freedom, stressing instead the historical and social constraints on human choice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments