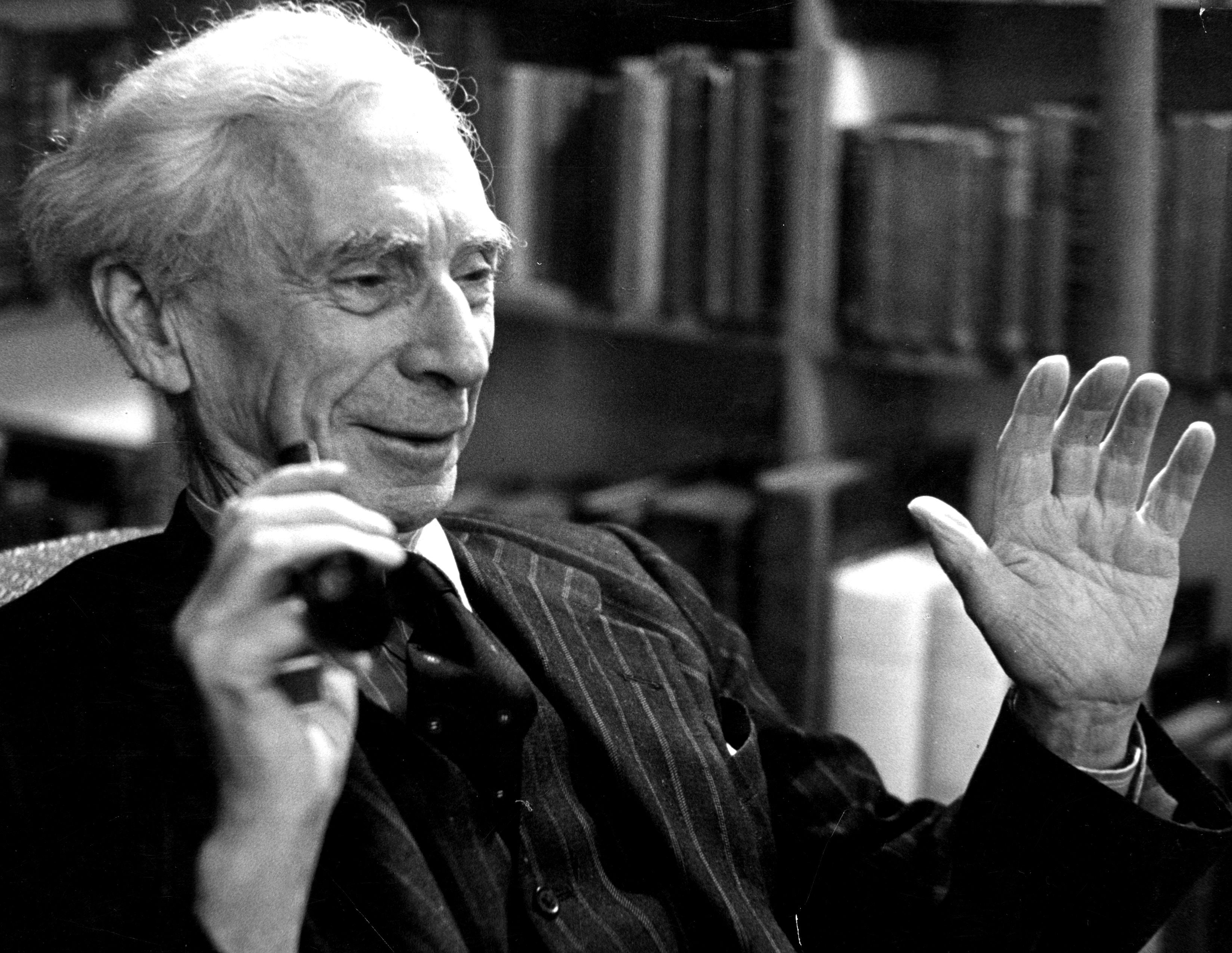

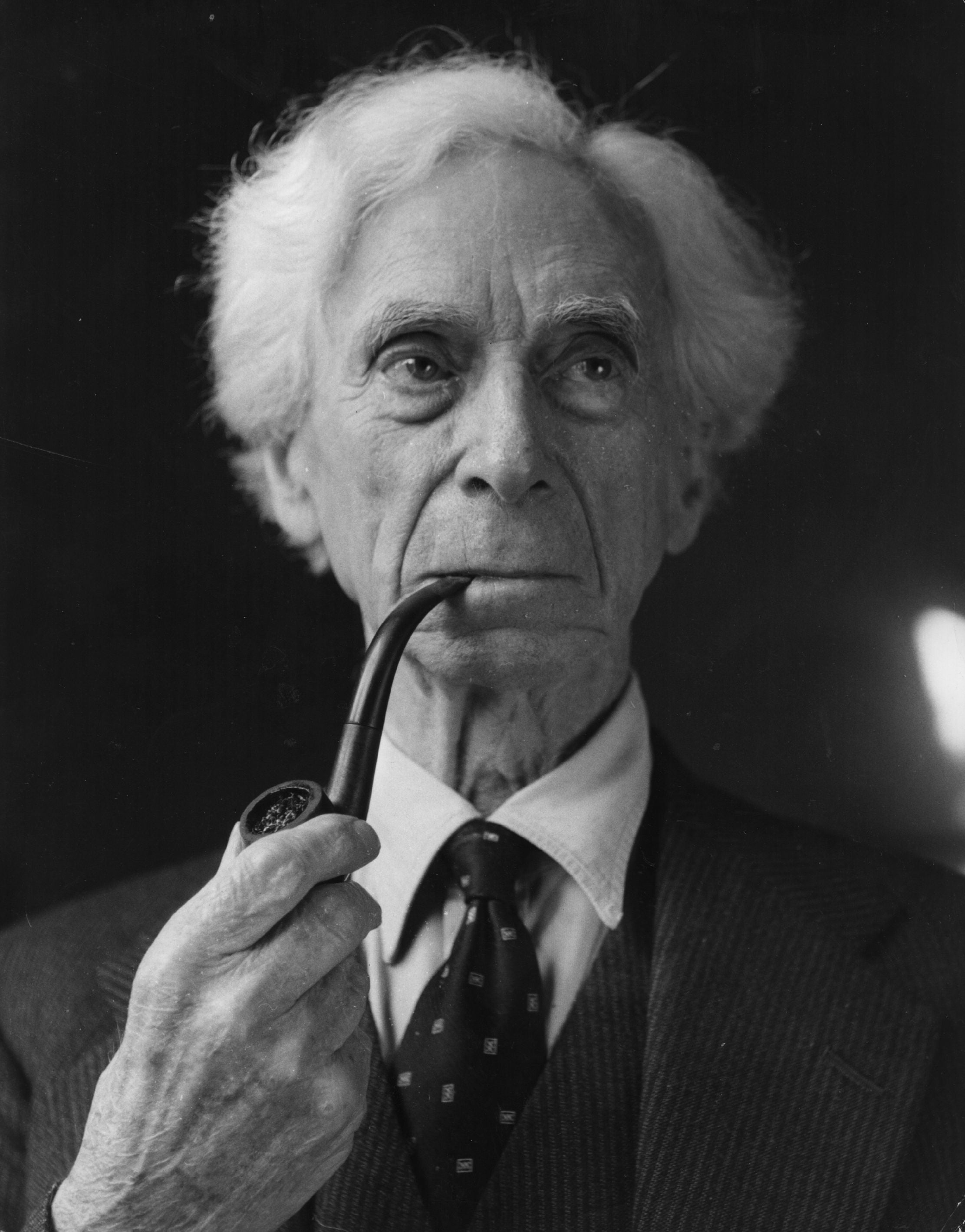

Bertrand Russell: One of Britain’s most famous philosophical commentators

Russell probably did more than anyone in the first decades of the 20th century to put philosophy on the course of logical analysis it generally still holds today

Generally recognised as one of the founders of analytical philosophy, Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) is perhaps Britain’s best-known, and most controversial, philosophical commentator of modern times.

Reflection on the life of Bertrand Russell, Third Earl Russell, can be a little tiring. He seems to have crammed a lot of living into a life that was unusually long. He probably did more than anyone in the first decades of the 20th century to put philosophy on the course of logical analysis it generally still holds today. It equipped him with a method, and using it he came to large conclusions in the philosophy of mathematics, metaphysics and epistemology. Without doubt, he was a brilliant mathematician, and according to some sources his insights into set theory had more than a little to do with the development of computing.

You might conclude from this that Russell was a wild-haired, desiccated calculating machine, detached from practical matters, but you would be quite wrong. Not only was he presentable and socially graceful, but he was an excellent stylist – he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950 – and his many public writings, particularly his History of Western Philosophy and The Problems of Philosophy, more often than not manage the rare combination of rigour and readability. He was also a very public figure, campaigning for civil rights and protesting against war and nuclear weapons, spending time in prison for his efforts. The story of his private life is a little darker and perhaps less admirable.

Russell was born in Trelleck, Monmouthshire, Wales, to Lord Amberley, oldest son of the First Earl Russell, and Kate Stanley, daughter of the second Baron Stanley of Alderly. His parents were dead by the time Russell was four years old, and this seems unusually tragic, both because he was then raised a little sternly by his austere, Unitarian grandmother and because Russell, by temperament, would have got on spectacularly well with his parents. He did not actually come to know much about them until he was 18, and it was probably with some delight that he discovered, as he writes with unconcealed pride in the first sentence of My Religious Reminiscences, that they were “considered shocking in their day on account of their advanced opinions in politics, theology and morals”.

Lord Amberley, for example, got himself thrown out of parliament when it was discovered he supported the use of birth control. Lady Amberley, for her part, spoke publicly in defence of women’s suffrage, somehow managing to annoy Queen Victoria, who allegedly fumed: “I wish I could whip that Kate Amberley.” The Amberleys were long-standing admirers of Bentham and Mill, and eventually became friends with the latter, contemplating the possibility of asking Mill to be the secular equivalent of Russell’s godfather. Given his parent’s early death, it is hard not to wonder what sort of philosopher Russell might have become had things turned out differently. A young Russell tutored at Mill’s knee is an image it is difficult to clear from one’s mind.

It seems to me that philosophical investigation, as far as I have experience of it, starts from that curious and unsatisfactory state of mind in which one feels complete certainty without being able to say what one is certain of

Russell took a place at Trinity College, Cambridge, to study mathematics, eventually turning to philosophy. He was appointed lecturer at Trinity, but his loud and public opposition to the First World War led to his dismissal and, eventually, a prison term. He was reappointed but finally resigned from Trinity, becoming dependent on popular writings for an income. He remained politically active throughout his life, well into his nineties, campaigning against America’s involvement in Vietnam and serving as a vocal proponent of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

His life was also marked by a number of turbulent marriages and disastrous love affairs, suggesting that Russell’s capacity for clear-headed thinking somehow deserted him in private life. His allegedly stunted capacity for emotion, which does not quite square with the occasional fervour of his public campaigns, is taken as the fundamental explanatory principle required for an understanding of Russell’s personality by some biographers. It is hard to know just what to think in this connection.

The revolt against idealism

When Russell came of age at Trinity, the final stages of an intellectual shift in British philosophy from empiricism to variations on the idealisms of Kant and Hegel were being articulated by FH Bradley. In Appearance and Reality, Bradley operates with a modification of the Kantian distinction between the mind-constituted world of appearances and the world as it is in itself. The distinction is roughly between propertied objects standing in causal relations to one another in space and time on the one hand and reality itself on the other, which Bradley takes to be something akin to the Hegelian Absolute, a single Cosmic Experience of which we are a small, self-conscious part. Odd tenets follow from the view. For example, the very idea of independently existing things (bacon sandwiches and plates) standing in relation to one another (the bacon sandwich is on the plate) is incoherent. Reality itself is unified, and the appearance of distinct objects, as well as relations between them, is illusory. “Truths” about particulars, on this view, can only be partial.

Along with GE Moore, Russell led the revolt against British Idealism. While Moore deployed arguments rooted in common sense and ordinary language, Russell’s arguments were grounded in logic and mathematics, the “logical-analytic method”. By expanding the scope of logic dramatically, along with AN Whitehead in the monumental Principia Mathematica, Russell shows that it is possible to restate propositions in a more rigorous and revealing logical form. This can sometimes uncover errors – such as vagueness, equivocation, or other sorts of confusions – in our everyday and philosophical talk. In addition to this and in direct reply to the idealists, Russell hoped to find a way to make talk of concrete particular objects, their properties and relations, logically respectable and clear, showing up confusions in idealist arguments in the process. The result was devastating to idealism, which more or less died the death in the English-speaking world, and it put logical analysis at the centre of 20th-century philosophising.

Although Russell’s various positions changed throughout his life – he made no apology for this, claiming that mental stagnation was far worse than the occasional revision of philosophical doctrine – he applied the same method to virtually all of the largest philosophical questions going. It might be that the method is more important than the answers he gives. He characterises his view of the process in this passage:

It seems to me that philosophical investigation, as far as I have experience of it, starts from that curious and unsatisfactory state of mind in which one feels complete certainty without being able to say what one is certain of. The process that results from prolonged attention is just like that of watching an object approaching through a thick fog … It seems to me that those who object to analysis would wish us to be content with the initial dark blur.

Even if we place a higher value on Russell’s method than the content of his thinking, this is to take nothing away from that content. There is no question that the content has had large implications for the philosophy of mathematics, epistemology and metaphysics.

The problem of the external world

Consider Russell’s response to the problem of how we know the nature of objects in the external world. Russell begins with reflections on perceptual experience. We seem to see tables, chairs and books in the room, but closer inspection reveals that we are not quite seeing what we normally take ourselves to see. We suppose, for example, that the table is brown, perhaps uniformly brown, brown all over. However, parts of the table reflect light differently, and if you move your head around you will notice that the reflective parts shift around too. The apparent shape of the table changes as well – from above it looks circular, but from the side it looks elliptical. Putting other heads, other points of view, into the equation complicates matters further. What then are we seeing when we claim to see a table? What’s the real table? “… [T]he real table, if there is one, is not the same as what we immediately experience by sight or touch or hearing. The real table, if there is one, is not immediately known to us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known.”

Russell calls the ever-shifting appearances “sense-data”. It is sense-data we immediately know, with which we are directly acquainted, and about which it is hard to think we might be wrong. What is needed is a connection between sense-data and objects, and here Russell admits that the view of objects as substances cannot stand. A new conception of objects as logical constructions built out of or inferred from sense-data is required. On at least one reading of Russell’s view (and Russell’s account changed over time), objects are sets or collections of perspectives. It is important to notice that this is saying something different and something less than that we infer the existence of an object (in the usual sense) on the basis of sense-data. Instead, Russell is claiming that the objects themselves are logical constructions, not substances out there causing sense-data, at least not in a straightforward sense.

You can wonder, maybe unkindly, what these constructions of perspectives are perspectives on, and in so wondering you might have made a syntactical error which a good student of logic might be able to clear up for you. You can also take it that Russell’s claims, to have any meat on the bones at all, have to be a form of inferential realism, the view that the existence of objects, even logically constructed objects, is somehow inferred from sense-data. If this is the right interpretation, you can object in the same way everyone objects to this sort of view: it seems to make the table invisible, and that can’t be right.

There is another, more general objection to Russell’s views and method, an objection he considered himself. All of this seems to make philosophy a branch of science or logic, seems to rob philosophy of what is most attractive about it, the speculative freedom or playfulness attending philosophical reflection. Reducing philosophical problems to complex, dry logical or mathematical matters makes the world boring. If this is true, Russell says:

… then it’s not my fault, and therefore I do not feel I owe any apology for any sort of dryness or dullness in the world. I would say this too, that for those who have any taste for mathematics, for those who like symbolic constructions, that sort of world is a very delightful one, and if you do not find it otherwise attractive, all that is necessary to do is to acquire a taste for mathematics, and then you will have a very agreeable world …

Many philosophers since Russell have taken this advice, a few going much further than Russell in circumscribing the limits of philosophical reflection to a more narrow range than even Russell would have liked. Still, the philosophical world as it is, no doubt because of the emphasis on logic in Russell’s writings, would be a very agreeable world to him.

Major works

Principia Mathematica (with AN Whitehead) (1910–13)

A massive, three volume explication of Russell’s theory of mathematics. It contains his important theory of types, as well as a defence of logicism, the view that mathematics is a part of logic.

The Problems of Philosophy (1912)

Still among the very best popular or introductory books of philosophy, this slim volume manages to combine philosophical integrity with a clear, readable style.

A History of Western Philosophy (1945)

This is probably Russell’s best-known work. It is a masterful treatment, a clear explication of the whole of western philosophy.

Bertrand Russell: Logic and Knowledge (1965)

A collection of some of Russell’s most important essays. It contains his “Lectures on the Philosophy of Logical Atomism”, the view that the world is made up of logical atoms – fleeting patches of colour or snippets of sounds, predicates, relations and the facts composed of these atoms.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks