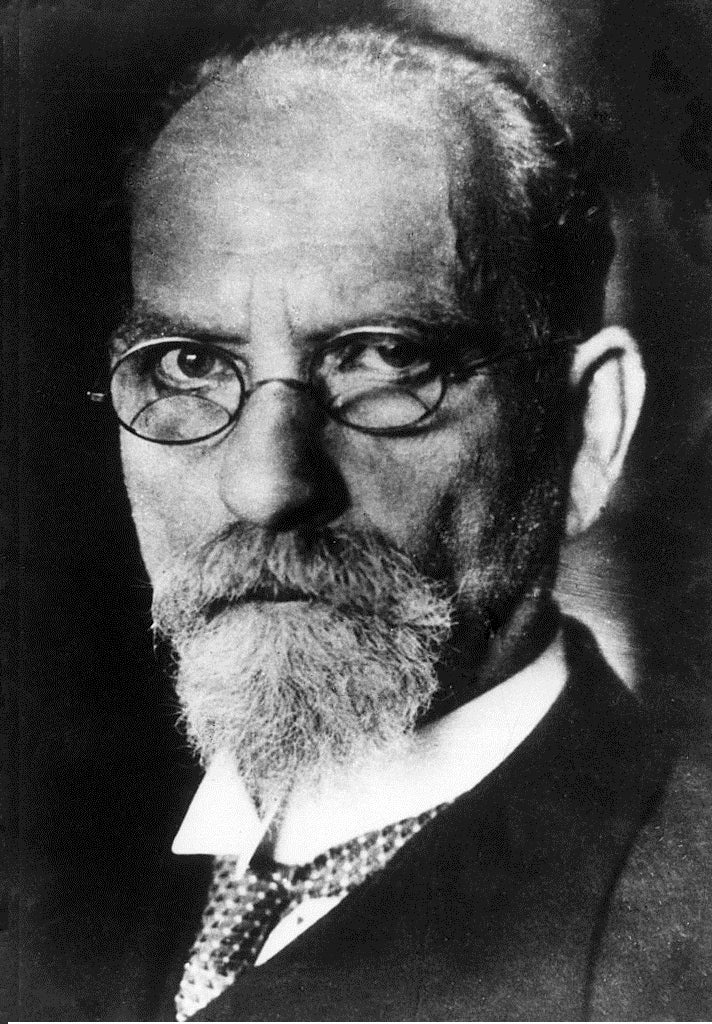

Edmund Husserl: What exactly is phenomenology?

Husserl’s position appears to be that what comes in from the outside is not sufficient to determine our consciousness of it

Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) was the originator of the philosophy of phenomenology, which would come into its own during the 20th century.

Husserl’s liking for new words, and new uses for old words, makes him a difficult philosopher to read. In the eyes of Husserl scholars, this is almost certainly a good thing, for they like nothing better than to entertain each other with talk of “epoches”, “eidetic reduction”, “noemata”, “horizons” and “hyle”. Normally, there would be little excuse for this kind of thing, but, in the case of Husserl, we can perhaps forgive him the technical vocabulary, for he did invent a new philosophical approach, one which dominated much of philosophy in the continental tradition in the 20th century.

He called this approach “phenomenology”, which, in its most general sense, consists of the analysis and explication of the structures of conscious experience. Husserl’s interest in consciousness can be traced to his formative years and the influence of his teachers.

He was born in Prossnitz, Moravia, then a part of the Austrian empire, and now in the Czech Republic, on 8 April 1859. When he was 10, his father, a clothing merchant, sent him to Vienna to begin his education proper at the Realgymnasium. Shortly afterwards, he moved a lot closer to home when he transferred to the public gymnasium in Olmuetz. Although he did not excel at school, he nevertheless developed a passion for science and mathematics. He graduated in 1876 and then went on to study physics, mathematics, astronomy and philosophy at the universities of Leipzig, Berlin and Vienna. He received his doctorate in 1882, with a dissertation titled Contributions to the Theory of the Calculus of Variations. Then he made what was perhaps the decisive move of his intellectual life when he went to Vienna to study with the German philosopher and psychologist Franz Brentano in 1884.

Brentano’s importance lies primarily in the fact that he developed the concept of intentionality, which is central to phenomenology. Intentionality refers to the directedness of consciousness; consciousness is always consciousness of something. Brentano famously put it like this in his book Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint: “Every mental phenomenon is characterised by what the scholastics of the middle ages called the intentional (or mental) inexistence of an object, and what we might call, though not wholly unambiguously, reference to a content, direction toward an object … Every mental phenomenon includes something as object within itself, although they do not do so in the same way. In presentation, something is presented, in judgement something is affirmed or denied, in love loved, in hate hated, in desire desired and so on.”

Husserl, in his turn, expressed it thus in Introduction to Phenomenology: “The terminological expression … for designating the basic character of being as consciousness, as consciousness of something, is intentionality. In the unreflective holding of some object or other in consciousness, we are turned or directed towards it: our ‘intentio’ goes out towards it.”

To give a very simple example, a person who has spent all their life in the Amazon jungle will see different things in the street than the person who has always lived in cities

This basic idea is fairly easy to understand: consciousness, in its various aspects, is always directed towards an object. Thus, for example, a person might perceive a dog; desire an ice-cream; judge a contest; remember a birthday party; or contemplate a sunset. However, in its details, it rapidly becomes much more complicated. For example, consider the case of hallucination: if a person thinks that they see a unicorn, given that consciousness is necessarily directed towards an object, is the unicorn then in some sense real? Brentano’s response – though it is still a matter of scholarly debate, and it is an issue about which he never reached a settled opinion – was that the object has a kind of existence within the realm of the mental. Husserl disagreed: he argued that consciousness is merely as if of an object; the existence, or not, of the objects of consciousness is a secondary matter.

Phenomenological reduction

The best way to get an idea of what Husserl had in mind here is to consider his notion of “phenomenological reduction”. This is perhaps the central phenomenological technique. It comprises a special way of attending to the objects that appear to consciousness. Rather than treating them as everyday objects – for example, the next door neighbour’s dog with the red collar – about which we already have ideas and theories, we treat them simply as appearances. We put their existence in “brackets”, suspend our “natural attitude” towards them, in order to consider them purely as they appear to consciousness; we remain neutral on the question of their existence.

Husserl hoped that by focusing on pure experience in this way it would be possible to learn something about the structure that constitutes the directedness of consciousness. However, this emphasis on the subjective elements of experience has led to the accusation that Husserl is some kind of philosophical idealist; that is, that he does not believe that the world has a reality which is independent of our experience of it. It is easy to see how people have come to this conclusion. Indeed, Husserl himself termed his approach transcendental idealism; moreover, he argued that consciousness constitutes its objects. Yet, at the same time, he claimed that it was indubitable that the world exists.

At first sight this might seem paradoxical, and certainly many commentators do find it so. Indeed, one of the major criticisms of Husserl’s approach is that he gets stuck in the realm of appearances; that, like Descartes, he has no easy way to move from the subjective into the objective. There is a certain irony in this because his wider project was aimed at establishing an objective foundation for all knowledge. He had been impressed with Descartes’ method of radical doubt, but felt it was not carried far enough, hence his insistence that in phenomenological reduction it is necessary to “bracket” all that we think we know about the world. However, the result is this tension between the subjective and the objective.

Consciousness and the external world

Despite this, there is at least the beginning of a way out from what seems to be the paradox of claiming that consciousness constitutes the objects to which it is directed and yet also that the external world has a reality of its own. Husserl’s position appears to be that what comes in from the outside is not sufficient to determine our consciousness of it. To understand how this might be, consider, for example, what happens when we look out on to a street on a foggy night. We will see shapes, yet precisely how these shapes appear to each one of us will vary according to our previous experiences, interests, cultural identity, and so on. To give a very simple example, a person who has spent all their life in the Amazon jungle will see different things in the street than the person who has always lived in cities. Consciousness in this way, then, structures what we see; it is constitutive of our experience of the external world.

The influence of phenomenology

Phenomenology has been hugely influential. In the world of philosophy, it underpins the work of such thinkers as Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Thus, for example, Heidegger dedicated his great work Being and Time to Husserl (though he later withdrew the dedication); and Sartre, in Being and Nothingness, stated that “all consciousness, as Husserl has shown, is consciousness of something”, and he used this insight as the foundation upon which to build his existential theory of human freedom.

Phenomenology has also been influential beyond the world of philosophy. For instance, in the social sciences, Husserl’s concept of the “lifeworld”, the taken-for-granted world of our everyday lives, has received much attention. The sociologist Alfred Schutz, for example, spent a good part of his intellectual life explicating the structures of the lifeworld as they are both constituted and experienced by human beings. Thus, in his book The Phenomenology of the Social World, he argued that we experience the lifeworld as our natural world, one that we take for granted and gear into in the pursuit of our projects and life-plans. Consequently, it requires something akin to a shock for us to break out of the bounds of this world to enter the realm of another world. According to Schutz, however, such shocks occur frequently in the course of our lives. He mentions, as examples, the shock of falling asleep as the transition into the realm of dreams; the Kierkegaardian “leap” into the world of religious experience; and the transformation that occurs as the curtain rises in a theatre.

It is hard to draw definitive conclusions about Husserl’s significance as a philosopher. Whilst it is true that the high point of phenomenology is now in the past, he remains a major figure in the continental tradition of philosophy. Moreover, a number of analytic philosophers, particularly those working in the philosophy of mind, have begun to take his work seriously. However, it is likely that he will always remain a slightly marginal figure in the pantheon of greats. There are a couple of reasons for this. First, his style of writing; it is fair to say that it is is not good, and it is undoubtedly a barrier to a greater appreciation of his work. Second, the fact that he did not complete the philosophical task that he set himself; in the end, his aim of establishing the firm foundations for all human knowledge went unfulfilled.

The last few years of his life were both eventful and difficult. The rise of Nazism led to him being denied the use of the library at the University of Freiburg, where he had taught until 1928, and to him being excluded generally from German academic life. He nevertheless continued to work, bolstered by the daily walks he took with his friend and research assistant Eugen Fink, visits from philosophical colleagues, and invitations to lecture abroad. In 1937, he became ill, and by the beginning of 1938 it was clear that he would not live much longer. He remained a philosopher to the end. At his death, he refused spiritual counselling, saying that he had lived as a philosopher and wanted to die as one.

Major works

Logical Investigations (1900-1901)

This work is made up of two volumes: the first is a criticism of “psychologism” in the study of logic; the second, an analysis of the key themes of the phenomenological method. These studies are generally considered to be Husserl’s first in the area of phenomenology.

Ideas (three volumes, 1913)

Very difficult exposition of the major themes of phenomenology. Introduces and/or develops many of the major concepts associated with Husserl’s approach, including intentionality, transcendental reduction, noema, noesis and hyle.

Formal and Transcendental Logic (1929)

As the title suggests, this book deals with the phenomenological foundations of formal logic. As with Ideas, it is a very difficult text for people not familiar with Husserl to get to grips with.

Cartesian Meditations (1931)

Perhaps the easiest of Husserl’s later works, it is a reworking and expansion of a series of lectures that were given at the Sorbonne in 1929. Its focus is primarily the phenomenology of the ego, and the processes that underpin and constitute intersubjectivity.

The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology (1936)

In this work, there is a move away from the more abstract concerns of the earlier works towards, instead, a concern with the lifeworld. This book is among the most influential of Husserl’s, particularly in that it played an important role in extending phenomenology into the social sciences.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments