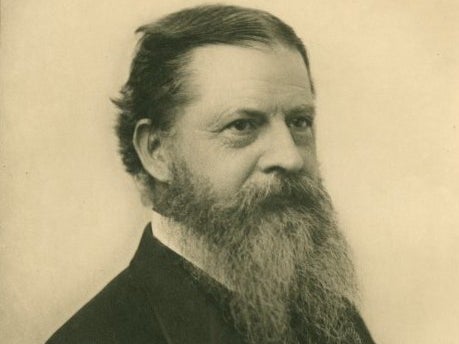

Charles Sanders Peirce: Immensely important if not fully realised

Throughout his articles, and with his famous pragmatism, Charles Sanders Peirce explored what it was to say that something was hard or heavy

Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) was unusual for a philosopher in that he published no major work outlining his thought. Nevertheless, his contributions to the subject are immense, if not yet fully realised.

Peirce is best known as the founder of pragmatism, or, as he later came to call it, ‘pragmaticism’. However, it would be a mistake to suppose that this was the extent of his intellectual interests, since he wrote prolifically on subjects as diverse as mathematics, economics, anthropology, the history of science, language, psychology, and more. Indeed, his published output runs to some 12,000 pages, and there are at least a further 80,000 extant pages which have yet to be published.

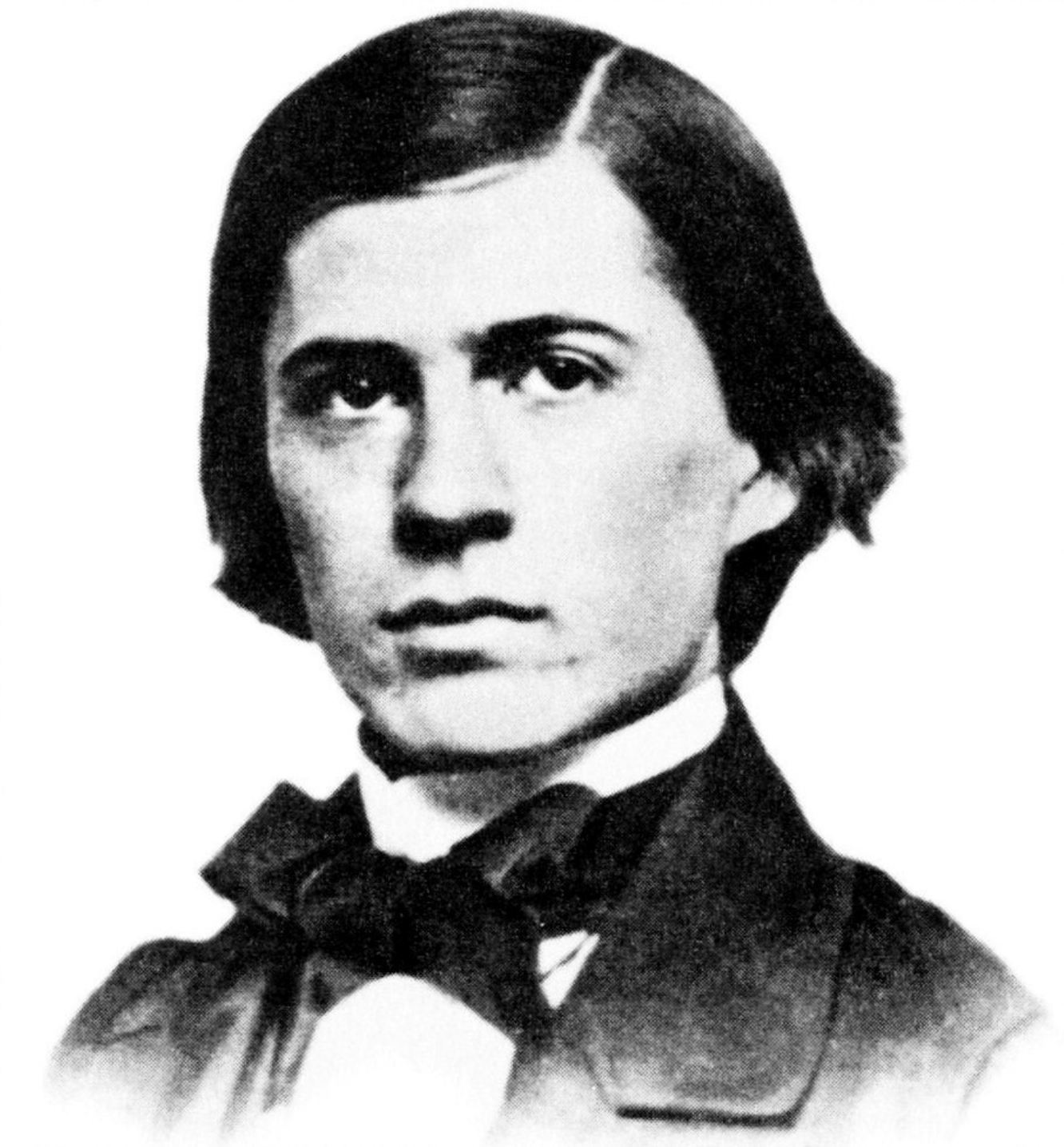

Peirce, the son of Harvard mathematician Benjamin Peirce, was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in September 1839. He was brought up in an atmosphere of intellectual excellence which befitted his father’s status as one of the country’s most esteemed mathematicians. Some of the top scientific and philosophical thinkers of the time were regular visitors to the Peirce household, and Charles was encouraged to be intellectually curious and independent from a very early age.

Benjamin Peirce took responsibility for his son’s education, and many commentators attribute Peirce’s originality to the didactic techniques his father employed. His normal method was to set Charles some problem to solve, to leave him to it, and then simply to check his solution.

As with many of the great philosophers, Peirce showed his abilities very early in life; by the age of eight, for example, he was studying chemistry, and at 13 he started to read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. However, he didn’t do particularly well as an undergraduate at Harvard, reportedly because he found things too easy to be interesting, coming only 79th out of a class of 90. He was soon to show his abilities, though, when he was the first student to graduate summa cum laude from Harvard’s Lawrence Scientific School.

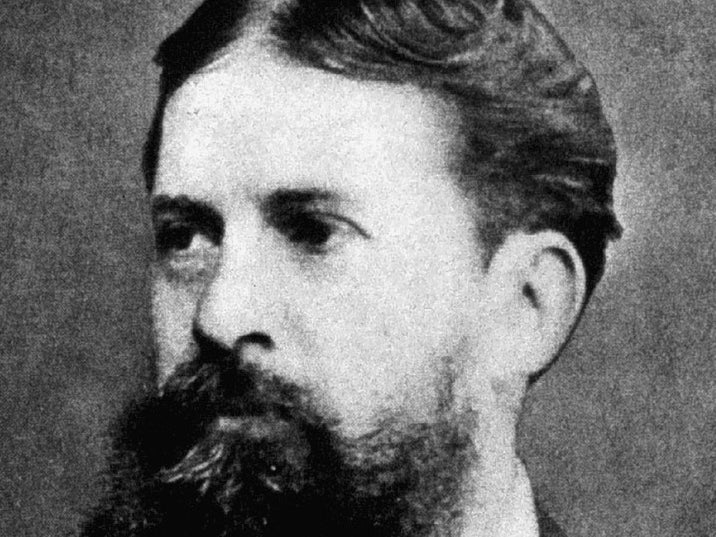

His next move turned out to be very important in shaping the tenor of his philosophy; he went to work for the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, with which he was to be associated for 30 years. The significance of this is that Peirce saw himself as a practising scientist, which is reflected in the concerns which drive his work. He called his pragmatism the philosophy of the laboratory scientist.

The essence of pragmatism

The central contention of pragmatism is summed up in a statement from his article How to Make Our Ideas Clear, which was published in Popular Science Monthly in 1878: “Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.”

In essence, what is being claimed here is that we get clarity about the content of a thought by working through the experimental consequences of the content of a thought or concept.

For Peirce this idea has some radical consequences; most particularly it led him to define truth as that about which there is a long-term consensus of opinion amongst a community of responsible inquirers

Peirce illustrates this idea with reference to the concepts of “hard” and “heavy”:

“Let us ask what we mean by calling a thing hard. Evidently that it will not be scratched by many other substances. The whole conception of this quality, as of every other, lies in its conceived effects. There is absolutely no difference between a hard thing and a soft thing so long as they are not brought to the test.” (How to Make Our Ideas Clear)

To say that a body is heavy means simply that, in the absence of opposing force, it will fall. This (neglecting certain specifications of how it will fall, which exist in the mind of the physicist who uses the word) is evidently the whole conception of weight. (How to Make Our Ideas Clear)

Thus, the concept of “hard” gets its meaning from the things which happen when we put hard objects to the test. For example, they don’t scratch, they don’t crumble when touched, they will dent soft objects, and so on. And similarly with heavy things; they fall when not supported.

A definition of truth

For Peirce, this idea has some radical consequences; most particularly it led him to define truth as that about which there is a long-term consensus of opinion amongst a community of responsible inquirers. The idea here is that, on any given issue, all investigators will eventually come to the same conclusion. This happens because real things have the effect of causing beliefs; therefore, given that there is only one reality, the beliefs of a community of responsible inquirers will eventually accord both with it and with each other:

“Different minds may set out with the most antagonistic views, but the progress of investigation carries them by a force outside of themselves to one and the same conclusion. This activity of thought by which we are carried, not where we wish, but to a fore-ordained goal, is like the operation of destiny. No modification of the point of view taken, no selection of other facts for study, no natural bent of mind even, can enable a man to escape the predestinate opinion … The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real. That is the way I would explain reality.” (How to Make Our Ideas Clear)

This idea is not without its problems. For example, it has been pointed out that there appears to be a strange contradiction in the argument. Reality is said to control and drive people’s beliefs; yet reality itself is constituted by a long-term consensus of agreement. Therefore, it seems that consensual opinion is driving people towards consensual opinion.

Though there may be logical problems with Peirce’s conception of truth, these do not significantly impact on the way in which he saw science in practice as proceeding – by means of the testing of propositions derived from hypotheses about the nature of the world.

In fact, in a fashion which anticipated more modern notions of scientific method, he saw scientific enquiry as proceeding according to three principles of inference: first, abduction, which refers to the generation of hypotheses for the purposes of explaining particular phenomena; second, deduction, which is the mechanism by which testable propositions are derived from hypotheses; and third, inference, which is the whole process of experimentation which takes place in order to test hypotheses.

Peirce was aware that in proposing a fallibilistic account of scientific progress, he was committed to the view that scientific truths are necessarily provisional. Indeed, he came to argue that one should never be committed to the truth of current scientific opinion, but rather merely accept it as a stage on the way towards truth. However, somewhat paradoxically, in line with his idea that reality is constituted by the long-term consensus of a community of inquirers, he was optimistic about the possibility of attaining final answers to particular questions. Indeed, so long as questions had genuinely testable consequences, then the truth about them would eventually be known.

A logical turn

Peirce’s ideas about pragmatism and scientific knowledge were outlined in articles written in the late 1870s. After this time, he turned his attention to logic, and with his students in 1883, he published Studies in Logic, which contained his version of the logic of what is called quantification. However, its publication coincided with a downturn in his fortunes. In 1884, he was effectively sacked from his university position, apparently after information about his errant behaviour – he was widely perceived to be a libertine of dubious morality and unorthodox religious beliefs – came to the notice of the university authorities. In 1891 his job at the United States Costal Survey also disappeared. This plunged him into poverty. Indeed, now living with his second wife in near-seclusion in Pennsylvania, and considered unemployable inside academia, he was dependent on occasional consulting work and the goodwill of friends like William James for his survival.

When Peirce died in 1914, his death went largely unnoticed in the philosophical community. However, since then, and particularly with the publication of the first volume of his collected papers in the 1930s, his reputation has undergone a renaissance. In this outline of his life and work, we have concentrated on his pragmatism and his ideas about science. However, for the professional philosopher, other areas of his work are of equal importance. In particular, he did interesting and original work on logic, semiotics and metaphysics. His significance as an intellectual figure is now coming to be fully appreciated. Max H. Fisch puts it like this:

Who is the most original and the most versatile intellect that the Americas have so far produced? The answer ‘Charles S. Peirce’ is uncontested … [He was] mathematician, astronomer, chemist, geodesist, surveyor, cartographer, metrologist, spectroscopist, engineer, inventor; psychologist, philologist, lexicographer, historian of science, mathematical economist, lifelong student of medicine; book reviewer, dramatist, actor, short story writer; phenomenologist, semiotician, logician, rhetorician and metaphysician.

All this, and yet with some 80,000 pages of his work still to be published, there is presumably more to come. It is fair to say, then, that Peirce lived up to his early promise.

Major works

Peirce did not publish any single philosophical work summarising or explicating his philosophical position, preferring instead to write technical articles for academic journals. Interested readers, therefore, would be best advised to consult a volume of his collected works, perhaps Houser and Kloesel’s two-volume The Essential Peirce (Indiana University Press). Of the many secondary sources available, The Cambridge Companion to Peirce (Cambridge University Press) is perhaps the best starting point.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks