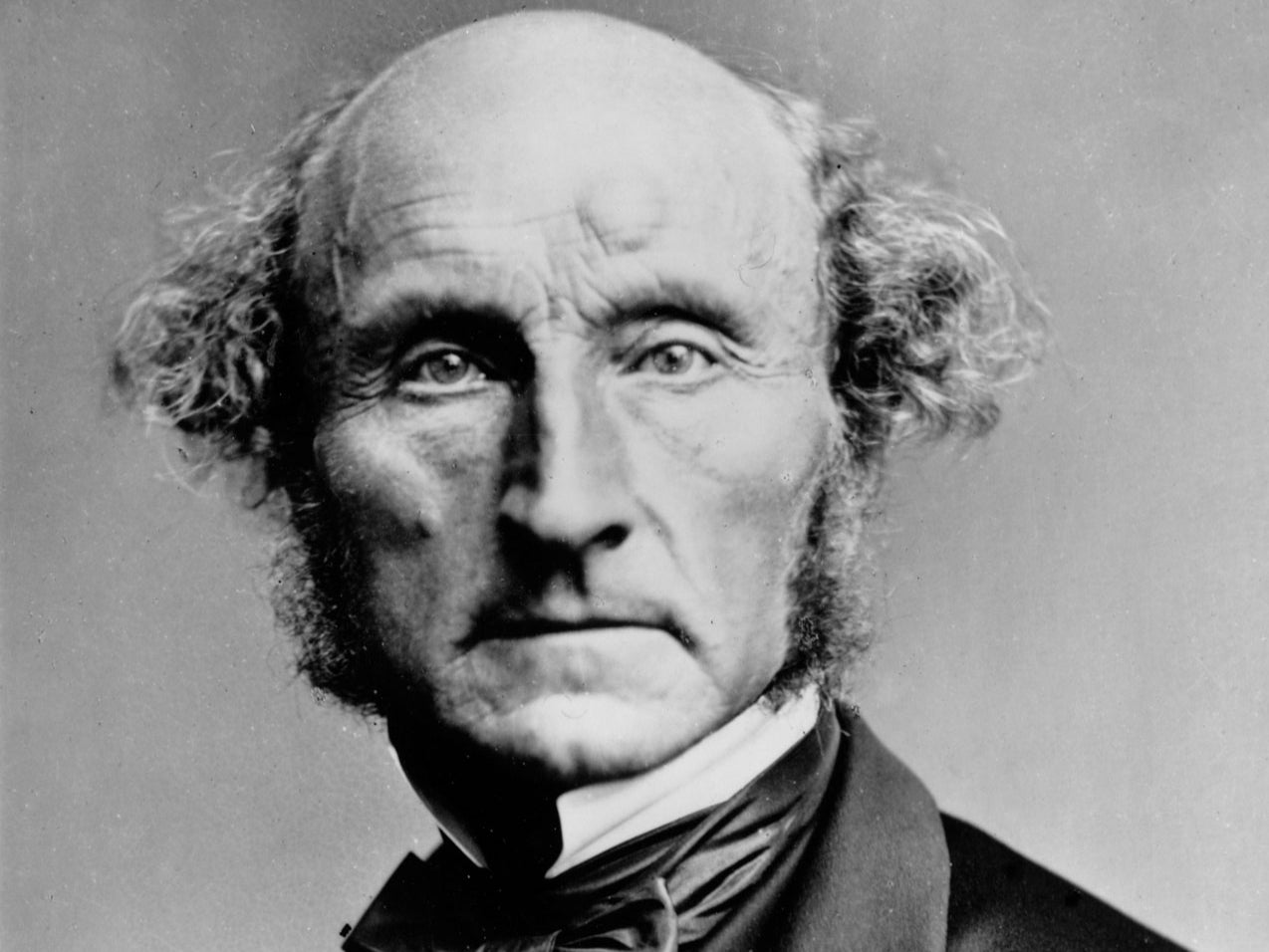

John Stuart Mill: The utilitarian prodigy

Reading Greek at the age of three and Latin at eight, John Stuart Mill was set to become one of Britain’s leading philosophical thinkers

John Stuart Mill’s (1806-1873) father, James Mill, was an outspoken advocate of utilitarianism and a friend of Jeremy Bentham, its founder. John Mill was born into a household steeped in utilitarian thinking, particularly Bentham’s views on education.

It was the aim of Mill’s father to educate the boy himself, in his own words, to turn him into “a mere calculating machine”. This James Mill more or less did, with alarming consequences.

John Mill could read Greek at the age of three and Latin at eight. By his early teens, he had read all the major Greek and Latin works, made an extensive survey of history and become well versed in jurisprudence, psychology, economics, mathematics and logic, according to his autobiography. His father lectured him on such subjects during long walks, requiring him to write up the lectures for the father’s consideration the next day. James Mill based a book, Elements of Political Economy, on a set of these papers. John Mill was just 14 at the time.

At 15, Mill read Theory of Legislation, the first published account of Bentham’s utilitarian views. The book changed him comprehensively: “I felt taken up to an eminence from which I could survey a vast mental domain, and see stretching out into the distance intellectual results beyond all computation.” It gave Mill a standpoint, a philosophical position rich enough to underpin views across the philosophical spectrum, and, he hoped, the means to improve human life generally. His whole life really had prepared him for just this revelation. “When I laid down the last volume of the [Theory],” he said with some reverence, “I had become a different being.” In addition to pursuing the study of law, the new Mill spent the remainder of his teens editing many of Bentham’s unpublished manuscripts, contributing to several journals with papers on current events, political debates and law, all from the utilitarian point of view.

At 20, perhaps predictably, the calculating machine suffered the worst of a series of nervous breakdowns, or at least deep bouts of depression. Already in a “dull state of nerves”, Mill reflected critically on his own happiness. He asked himself if he actually would be happy if all his aims were realised, if all his planned improvements to institutions and law were affected. On discovering that not even this could please him, he plummeted into a kind of hopeless anguish.

Mill had been well-prepared for argumentation and analysis, but it seems he had no training to help him cope with the vagaries of emotion. It will send a Freudian chill down your spine to learn that he was brought out of this depression while reading about a boy who became an inspiration to his family following his father’s death. It perked Mill up, and he returned to his work, supplementing it with a new interest in poetry, culture and the arts, which, it seems, formed a part of the cure too.

Utilitarianism

You will recall that Mill cured his depression, in part, with the finer things in life, and it might be that which clouds his judgement

Mill became probably the foremost English-speaking thinker in the 19th century, and certainly, he is among the most influential and wide-ranging. In addition to studies of jurisprudence, economics and psychology, his philosophical work spans analyses of language, logic and mathematics, as well as scientific methodology. He has clear views on the relationship between inner mental states and the external world, formulating the first expression of phenomenalism, the view that physical objects are permanent possibilities of perception. It is, however, his writings in ethics and politics that have received the most attention, most notably Utilitarianism and On Liberty.

Mill’s general aim in Utilitarianism is to defend and expand upon Bentham’s view that good acts are those that produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Happiness is construed here, as it is in Bentham’s writings, in terms of the intrinsic worth of pleasure. Although the book is a complicated one, we’ll consider just one aspect of Mill’s defence and one aspect of Mill’s expansion on Bentham’s conception of utilitarianism.

Suppose we think along the following lines, like a good utilitarian. Acts that produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number are good. It is the end, happiness, which makes actions good. Happiness itself is understood in terms of pleasure, and it is pleasure that has a special sort of value for the utilitarian. What proof have we that pleasure has this sort of value, the sort of value that carries a moral consequence, namely, that we ought to pursue it as an end? In one of the most perplexing passages in the book, Mill seems to offer the following proof:

The sole evidence it is possible to produce that anything is desirable, is that people do actually desire it. If the end which the utilitarian doctrine proposes to itself were not, in theory and in practice, acknowledged to be an end, nothing could ever convince any person that it was so.

The claim seems to be that pleasure is actually desired by everyone, so it is, therefore, desirable, valuable in the required way for a moral demand, something we ought to pursue. Mill goes on to say that the only things visible are things seen; the only things audible are things heard. Similarly, the only things desirable are things desired, and what everyone desires is pleasure.

First of all, it is not clear that the analogy works. Visible things are things that can be seen; audible things are things that can be heard. Mill needs it to be true that things desired are things that ought to be desired, not things that can be desired. As Bertrand Russell puts it, the argument is “so fallacious that it is hard to understand how he can have thought it valid”.

After all, Mill is proposing a moral system: everyone ought to act in such a way that actions bring about a greater balance of pleasure over pain. The proof of the claim that people ought to desire pleasure cannot be just that people do desire pleasure. We cannot infer what ought to be the case from what actually is the case. Further, what becomes of the moral weight of utilitarianism if it turns out that Mill is right? What is the point of arguing that people ought to desire pleasure if they are going to desire pleasure anyway?

Second, is it true that people, in fact, desire pleasure? For Mill’s line of argument to work, it has to be true that when I desire something, I desire that thing because of the pleasure getting it will give me. My desire, really, is for pleasure. This may sometimes be so, but when I desire a beer, for example, I really do desire the beer first and foremost – the pleasure is, for me, a secondary thing. You can complicate the question if you like by thinking about the possibility of individuals who explicitly deny that they desire pleasure. A masochist might tell you that they desire pain, maybe muddying the waters by explaining that they derive pleasure in a secondary way from their ultimate desire, pain.

Mill’s expansion on Bentham’s conception of utilitarianism consists, in part, of a consideration of not just the quantity of “pleasure derived from an action, but its quality. Bentham’s hedonistic calculus, complex as it was, does provide an algorithm for choosing between actions on the basis of the amount of pleasure produced, but it does not take account of distinctions between the quality of different pleasures. Mill takes it that some pleasures are of a finer quality than others and further that such higher pleasures are more desirable than others. Why think the “higher pleasures” are more valuable than the base ones? Further, is there a clear way to tell the difference between them? Mill’s answers might be gleaned from this passage:

Few human creatures would consent to be changed into any of the lower animals, for the promise of the fullest allowance of a beast’s pleasures; no intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no instructed person would be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and conscience would be selfish and base, even though they should be persuaded that the fool, the dunce, or the rascal is better satisfied with his lot than they are with theirs.

Mill’s claim here is that a person who has experienced both back rubs and poetry, both a full stomach and Mozart, will notice something having to do with the purity, sublimity, depth and refinement of higher pleasures that leaves base pleasures far behind, no matter the quantity. A person who has experienced both sorts of pleasure will be able to tell the difference between them and see that one is of a different and preferable kind to the other.

You will recall that Mill cured his depression, in part, with the finer things in life, and it might be that which clouds his judgement. He seems to be saying that the painful life of a dissatisfied intellectual is to be preferred to an idiot’s life of simple pleasures. Is this compatible, at all, with the principle of utility?

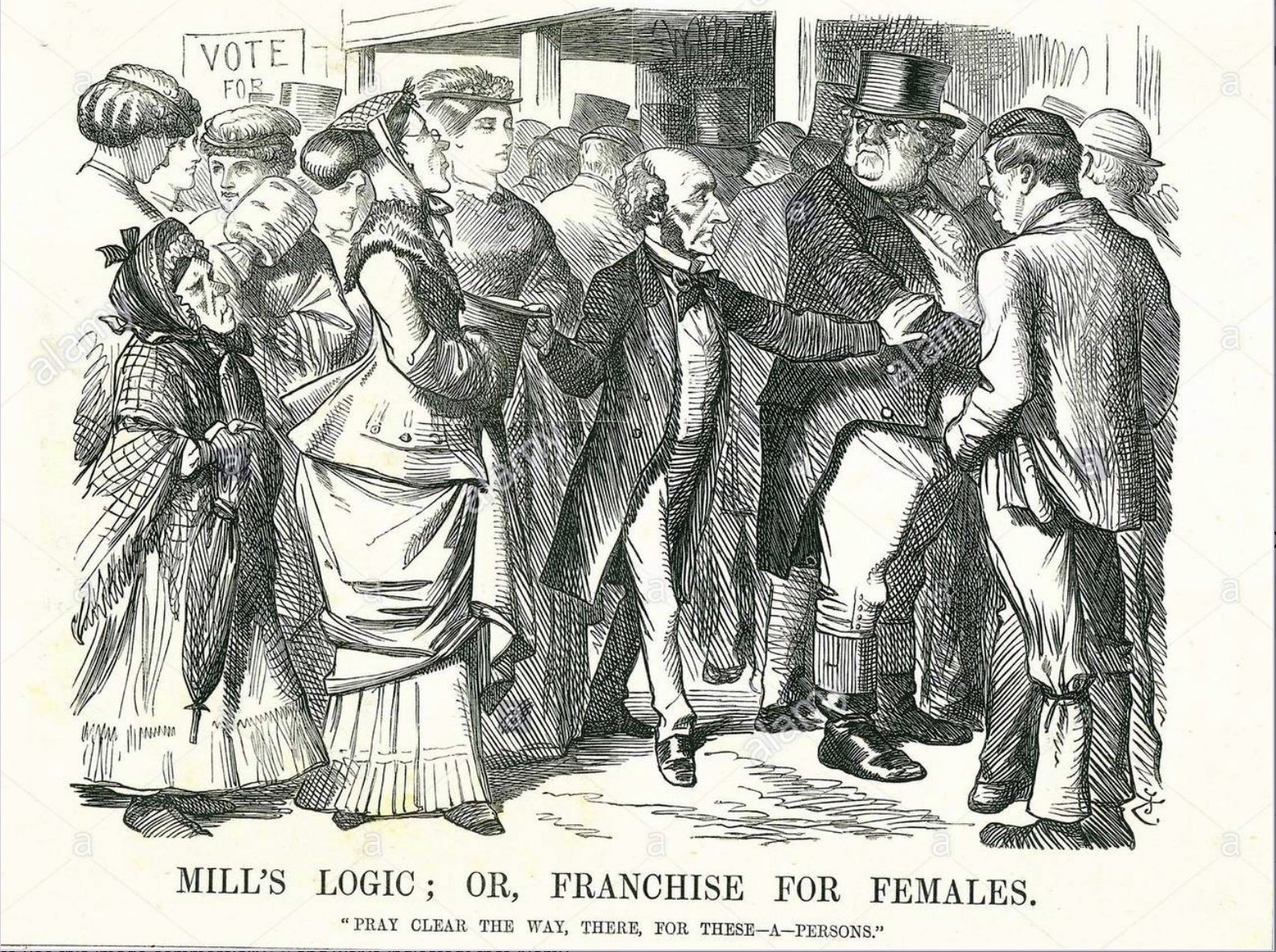

Much of what Mill claims in On Liberty clearly follows from reflections on utilitarian principles coupled with Mill’s view of what is best in us, our capacity for self-improvement and the determination of our own routes to happiness. Mill maintains that self-development, individuals pursuing their own aims, is among “the essentials of human wellbeing”. Thus, individual liberty gets star billing in Mill’s politics.

He argues for the following curb on the powers of government: “… the only purpose for which power can rightfully be exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.”

It is possible to wonder just how far Mill departs from Bentham in this connection. Bentham’s initial aim in working out the principle of utility was to provide lawmakers with a way of coming to reasoned conclusions about what is best for everyone. A Benthamite lawmaker ought to formulate laws for the good of the citizens, ought to curb individual activities in an effort to make the citizenry happier. Mill denies this explicitly. People should be able to do what they like, even to the extent of jeopardising their own happiness, so long as they harm no one else.

This is not as far from the letter of utilitarianism as one might think. Mill maintained that the state adopting this principle has happier people in it than one which does not. Given the alarmingly comprehensive powers of modern states over their citizenry, and the regular attempt on the part of such states to justify their more dubious activities in terms of what is best for us, it is hard not to think Mill was right to want to restrict political power in this way.

Major works

System of Logic (1843)

An expression of Mill’s radical empiricism. In it, he argues that even the laws of logic are empirical in nature. The work also includes an important consideration of induction.

On Liberty (1859)

Deals with the conflict between minority rights and the rule of a democratic government. It contains the excellent suggestion that an individual ought not to be compelled by a government to do something merely for his own good.

Utilitarianism (1861)

Mill’s attempt to expand upon Bentham’s conception of utilitarianism. In particular, Mill offers a treatment of the qualitative aspects of pleasure and pain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks