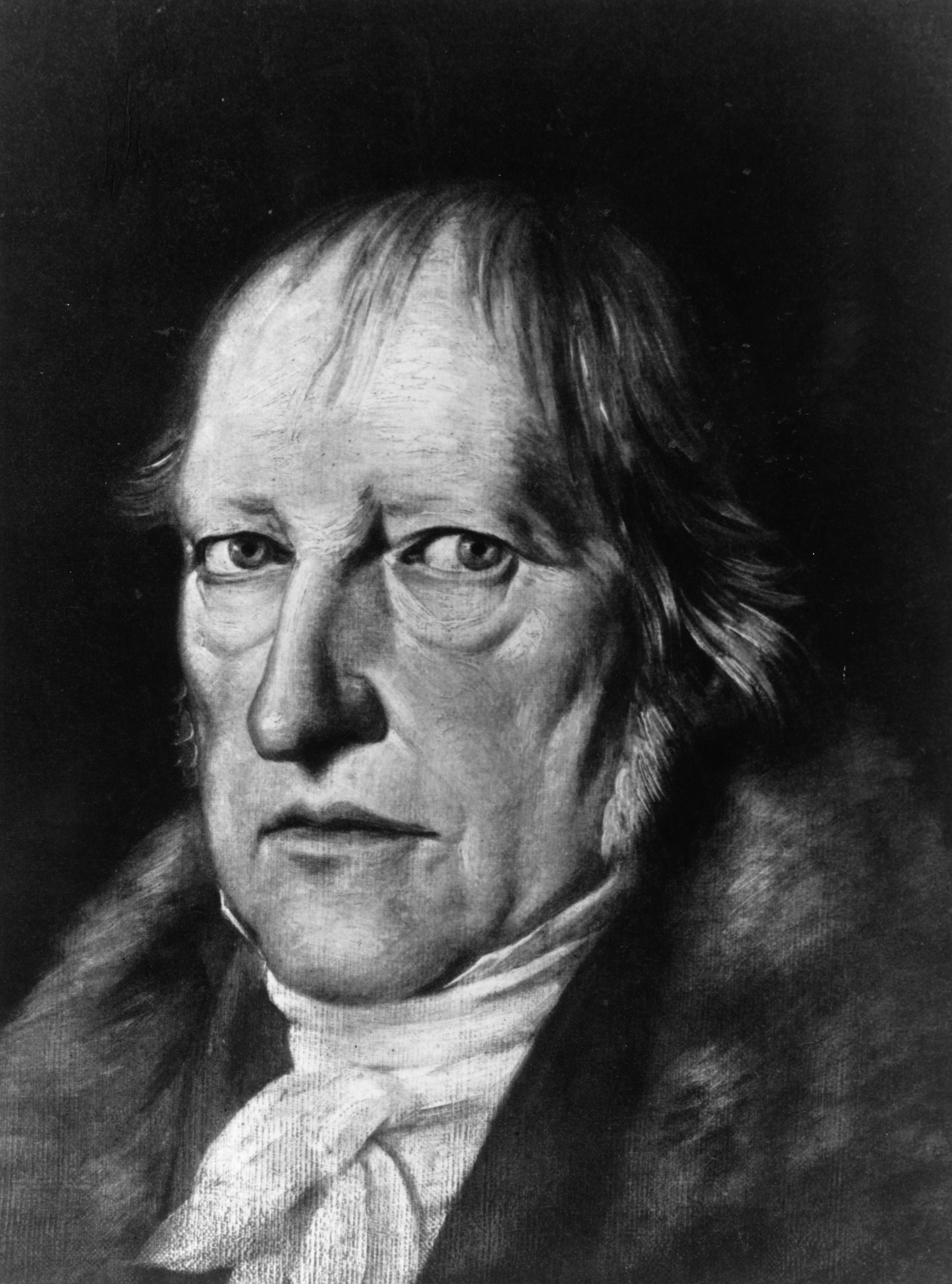

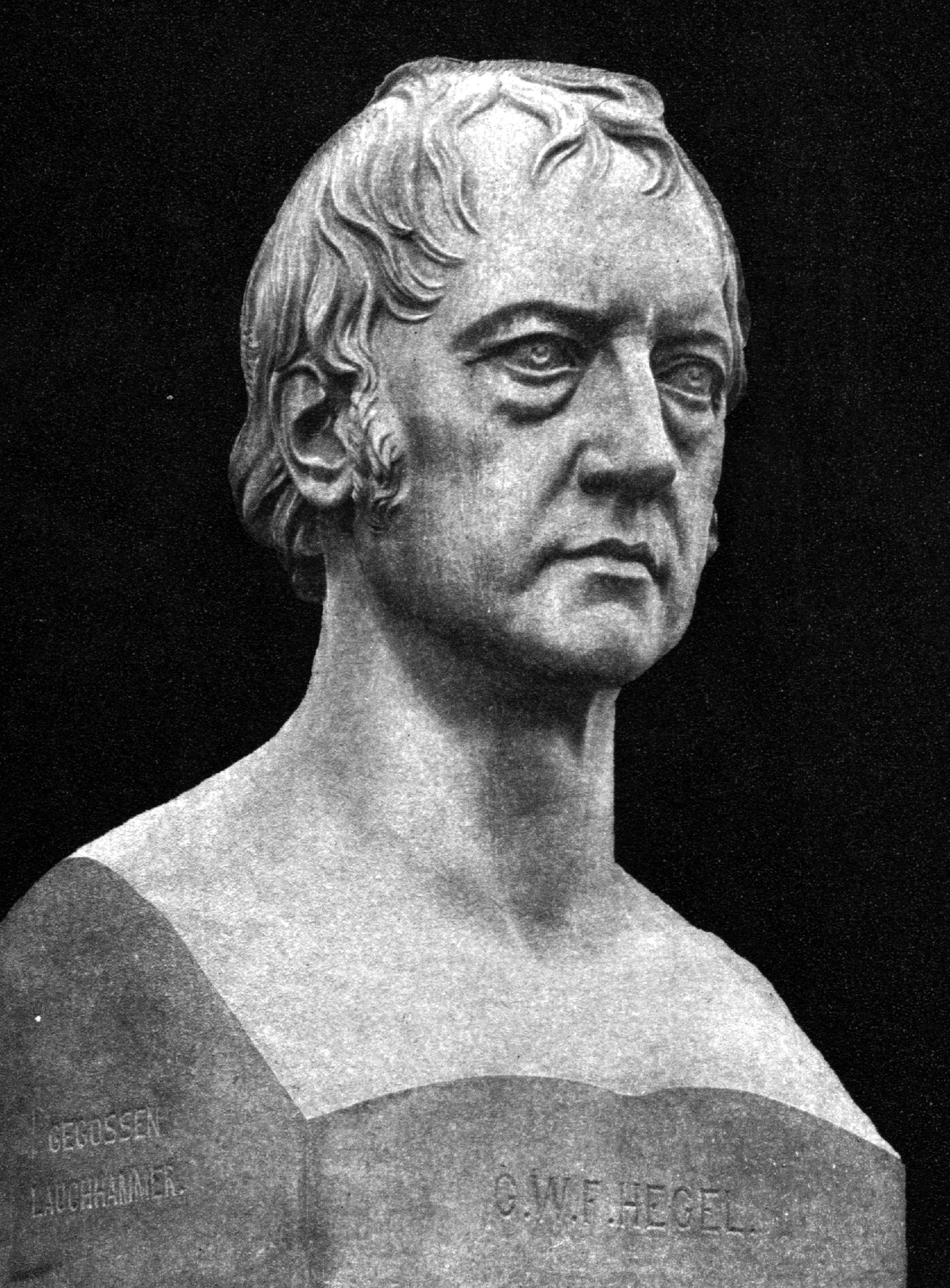

Georg Hegel: Extremely influential yet almost impossible to understand

Hegel’s aim was nothing less than to develop the conceptual apparatus necessary to understand the whole of reality

Georg Hegel (1770–1831) occupies a rather strange position in the history of philosophical thought: he is both extremely influential and almost impossible for a non-specialist to understand.

Two of Hegel’s most important works, The Phenomenology of Spirit and The Science of Logic, contain some of the most difficult philosophical writing which has yet appeared. Indeed, the impenetrability of his prose has led some people to suspect that he was a charlatan; that he deliberately obfuscated in order to create the appearance of profundity where, in fact, none existed.

However, this is to be uncharitable; Hegel’s is a systematic philosophy – indeed, he is arguably the last great system builder in philosophy – and at least some of the difficulty of his work is linked to the magnitude of the task he set himself. His aim was nothing less than to develop the conceptual apparatus necessary to understand the whole of reality, or, as he called it, Absolute Spirit. But even so, close reading of his work will eventually bear fruit; certainly it is possible for readers without a background in philosophy to get something from texts like Lectures on the Philosophy of History and The Philosophy of Right.

Hegel was born on 27 August 1770 in Stuttgart. As the son of an official in the government of the Duke of Wurttemberg, he enjoyed a comfortable, middle-class upbringing. He was educated at the local grammar school, and although he did not show the precocious abilities of a Pascal or a Peirce, he was nevertheless a first-class student. His taste for systematic and methodical work was evident even in these early years: for example, as a schoolboy, he kept a diary in which he carefully charted the progress of his reading; and at the age of 16, he started an alphabetised collection of the detailed notes he took from the books he read.

“His father wanted him to become a clergyman, so in 1788, Hegel entered the Protestant seminary at Tubingen. Although he successfully completed his studies there, his teachers reported that whilst he had excelled in philosophy, he had not appeared particularly interested in theology. Not surprisingly, then, he decided against a career in the church, and instead pursued his ambition to attain an academic position; this he achieved, with the help of his friend Schelling, when he took up a post at the University of Jena in 1801.

In Hegel’s scheme, self-consciousness emerges when consciousness recognises the reflection of itself in the objects towards which it is directed

It was while he was at Jena that Hegel put together The Phenomenology of Spirit, probably his most famous work. In it, he attempted to show, roughly speaking, how consciousness develops via a dialectical process, until it recognises that it is identical with the whole of reality, which itself is pure thought or spirit. Unfortunately, this idea is every bit as complex as it sounds. Perhaps the most fruitful way to gain a sense of it is to consider what is involved in the idea of dialectical progress.

The dialectical method

Hegel’s dialectical method is best understood in terms of the concepts of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Put simply, the idea is that any given phenomenon (thesis) contains within itself contradictory aspects (antithesis) which require a movement towards resolution (synthesis); and that progress in our understanding of reality occurs according to an iterative process which has this dialectical form. It is possible to illustrate this idea by looking at how Hegel thought that an individual self-consciousness moves towards self-certainty.

The idea of self-certainty is a complex one; however, it seems to be most clearly expressed by the notion of “belongingness”. Hegel had in mind that self-consciousness aims towards a situation where there is nothing in external reality that is alien to it; where, in a strong sense, self-consciousness is synonymous with the reality which it constitutes. Part of the significance of this journey to self-certainty is that it underpins the original relationship between self-consciousness and things which are other to it.

In Hegel’s scheme, self-consciousness emerges when consciousness recognises the reflection of itself in the objects towards which it is directed. Thus, “consciousness of another, of an object in general, is in fact necessarily self-consciousness, reflectedness in self, consciousness of oneself in one’s other”. However, while self-consciousness requires an external object to define itself, it is at the same time threatened by this object. The external object is foreign to the self; it is an otherness, in the face of which self-consciousness is unable to attain self-certainty. Thus, in a state of desire, self-consciousness seeks to negate the otherness of the external object by assimilating it. In the words of Hegel, “self-consciousness presents itself here as the process in which this opposition is removed, and oneness or identity with itself established”.

However, with the negation of the otherness of the external object comes a difficulty: if this entails the object’s destruction, then self-consciousness, dependent upon the moment of otherness, is robbed of the foundations of its own existence.

Therefore, self-consciousness requires an object which can be negated, whose foreignness can be annulled, without the object itself being destroyed. According to Hegel, only another self-consciousness fulfils this requirement, since only this is able to effect its own negation, and yet remain an external object. Specifically, he claims that a self-consciousness must seek the “acknowledgement and recognition of other self-conscious beings; only in this way can it attain the self-certainty it desires.

Master and slave

With this insight, therefore, that “self consciousness exists in itself and for itself, in that, and by the fact that it exists for another self-consciousness”, we are led to the famous dialectic of master and slave. Although mutual recognition between self-consciousnesses will ultimately bring the self-certainty that these seek, this will not be easily won. At first, neither self-consciousness is certain of the truth of the other – as self-consciousness – and hence both are deprived of the source of their own certainty. Consequently, each will try to attain the recognition of the other without reciprocating.

According to Hegel, the resulting struggle – for one-sided recognition – is necessarily to the death, because, in risking their own lives, these self-consciousnesses can demonstrate to each other, and to themselves, their freedom from their particular bodily forms, and hence their status as beings for themselves. However, it is clear that in this context the death of either participant would be irrelevant, since it would completely deprive the survivor of recognition. Hence, the solution to the struggle for one-sided recognition, which must put the life of each participant in danger, is the enslavement of one and the mastery of the other: “The one is independent, and its essential nature is to be for itself; the other is dependent, and its essence is life or existence for another. The former is the Master, or Lord, the latter the Bondsman” (The Phenomenology of Spirit).

“However, it is Hegel’s view that the opposition between individuals is something which will in time be overcome. The dialectic of master and slave, and the conflict that this entails, is simply one of the phases that self-consciousness must pass through on its way to self-certainty. Interestingly, it is the slave, and not the master, who takes the next steps on the journey; transformed by the experience of work, the slave comes to possess the intellectual tools necessary to progress to a greater self-understanding.

The philosophy of history

Hegel employed a similar dialectical method in order to analyse the unfolding of human history. In his view, human history is characterised by the move towards greater freedom, rationality and understanding. As he put it in the introduction to Lectures on the Philosophy of History, “The history of the world is none other than the progress of the consciousness of freedom.”

In this book, which was compiled from lecture notes after his death, he tracked this progress of freedom through the examples of various kinds of society. Thus, in ancient oriental regimes, such as China, only the despot is free; the people who make up the populace of these societies lack even the knowledge that they have the ability to make autonomous judgements. Although Hegel thought that the citizens of the city-states of ancient Greece enjoyed a certain truncated freedom, he said that it was only with the Reformation that the idea of individual freedom found proper expression. History from this point on can be understood as the series of changes which societies underwent in order to get to grips with this new concept of freedom. Thus, the Enlightenment, though it led to the excesses of Jacobin terror, and demonstrated that there could be no absolute break with the past, was nevertheless an attempt to reconstruct modern societies in terms of the precepts of abstract universalism.

In Hegel’s view, once an awareness of freedom has come to exist, it will eventually triumph; and in an echo of Rousseau, he said that politics then is about building communities which enable individuals to live out a freedom that is based upon their common ability to reason.

Hegel’s ideas have had enormous impact on social and political thought over the last two hundred years. Most famously, Marx employed Hegel’s dialectical method in the development of his historical materialism; indeed, in the early part of his life, Marx, along with people like Bruno Bauer and Ludwig Feuerbach, considered himself to be a young Hegelian. Sartre’s existentialism was also heavily indebted to Hegel; particularly, his analysis of being for others is predicated on a development of the insights contained in the master and slave section of The Phenomenology of Spirit.

However, it is also true that the kind of philosophy that Hegel represents, namely, the tradition which is fond of grand metaphysical speculation, has fallen on hard times. In particular, the rise of logical positivism in the 20th century, with its claim that statements are meaningful only if they are true by definition or empirically verifiable, undermined the appeal of a philosophy like Hegel’s. AJ Ayer, for example, in his Language, Truth and Logic, had no difficulty in showing that Francis Bradley’s Hegelian-inspired version of idealism was constructed out of claims that were not in any obvious way meaningful. Indeed, for many people working in the analytic tradition of philosophy, Hegel’s kind of philosophy is precisely what has to be avoided in order to produce good work. Therefore, whatever one thinks about the merits of his philosophical system, it is almost certain that we won’t see the like of Hegel again for quite some time.

Major works

Phenomenology of Spirit (1807)

Hegel’s most celebrated work. Employing his characteristic dialectical methodology, it tracks the unfolding of being, or absolute spirit, across the whole of history. It is an extraordinarily difficult book, but also hugely influential, setting in motion a whole tradition of philosophy in the nineteenth century.

The Science of Logic (1812–1816)

It sets down, systematically and in detail, the basis of Hegel’s metaphysical logic. The dialectical method is employed in order to articulate the abstract categories of thought, with the conclusion in the end being that reality is constituted by the absolute.

Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1821)

The most mature statement of Hegel’s social and political philosophy. In it, Hegel suggested that the most rational state was similar to the existing Prussian monarchy. For this he was accused of selling out, and it led the Young Hegelians to develop their own version of Hegelianism, one which in their eyes was nearer to the spirit of the real Hegel.

Lectures on the Philosophy of History (1833–1836)

One of the easiest entries into Hegel’s ideas, compiled from lecture notes after his death, it tracks the progress of freedom across time and in the context of different kinds of society.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments