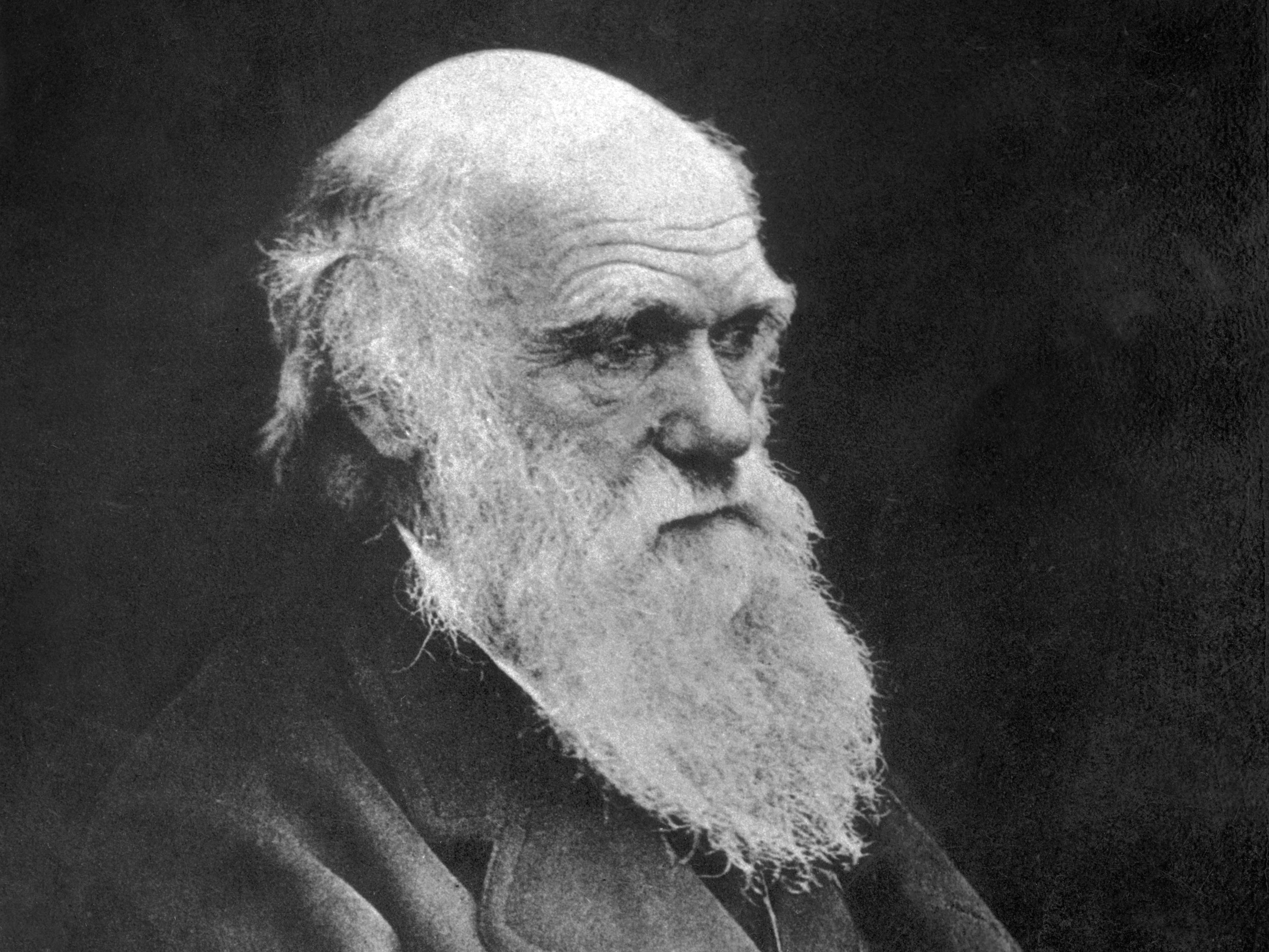

Charles Darwin: The single most powerful idea in the sciences and humanities?

Until Darwin it was hard to see how the natural world could have been anything other than designed

There are a number of candidates for the single most powerful idea in the history of the sciences and humanities. Nicolaus Copernicus’s heliocentric view of the Earth’s place in the universe is certainly one, as is Einstein’s theory of relativity. However, for the breadth of its application, and the impact that it had on modern civilisation, it would be hard to beat Charles Darwin’s (1809–1882) theory of evolution by natural selection.

Until Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species was published in 1859, it was hard to see how the natural world could have been anything other than designed. The significant point here is its complexity. As William Paley famously argued, it seems almost unimaginable that something as complex and highly wrought as the human eye could possibly have emerged purely by natural mechanisms. The eye just appears too precisely specified to be anything other than the creation of an intelligent entity (by which just about everybody means God). Darwin’s importance is that he showed exactly how this kind of “design” could have occurred without a designer.

Darwin was influenced by Thomas Malthus’s famous essay on population, in which Malthus argued that the capacity of a population to sustain itself tends not to keep up with its rate of growth. The lesson that Darwin took from this is that the living world is necessarily thoroughly competitive (“red in tooth and claw”, as one of his disciples later put it). Life is characterised by a struggle for existence – or, more exactly, for reproduction – since any species will tend to produce more individuals than can be sustained. It was this insight that led Darwin to his theory of evolution by natural selection.

Every species manifests some variation in the inherited traits of its members. Take foxes, for example: some foxes will be able to run faster than other foxes; some will have better eyesight, better hearing, sharper teeth and better camouflage. Variations that give an individual a competitive advantage (eg sharper teeth and better eyesight) will tend to be passed on more often than variations that put an individual at a disadvantage (eg a birthmark that makes its bearer a sitting target). Therefore, given enough time, helpful variations will come to be much more numerous than less helpful variations. So long as there are always new variations for natural selection to operate upon, then evolution will carry on in this way indefinitely.

This is a hugely powerful idea. It answers Paley’s challenge to explain how the eye could have emerged naturalistically: by means of tiny, incremental steps, each one beneficial in its own right. In Darwin’s day, the mechanisms of inheritance, and the source of the variations upon which natural selection works, were not known. It was only at the turn of the 20th century, with the rediscovery of the ideas of Gregor Mendel, that this became clearer. One hundred years later, we now know that genes are the units of inheritance; and that, every so often, they mutate to produce new characteristics in an organism, which are then subject to Darwinian selection.

Darwin’s importance simply cannot be overstated. He was the founder of modern biology; the person who, in Huxley’s phrase, put the world of life into the domain of natural law.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments