The fall of Saigon: ‘Nobody wanted to be left behind’

The panic and distress of the final days of the Vietnam War were captured in a single photograph. Forty-five years later, Mick O’Hare revisits a tumultuous time in world history

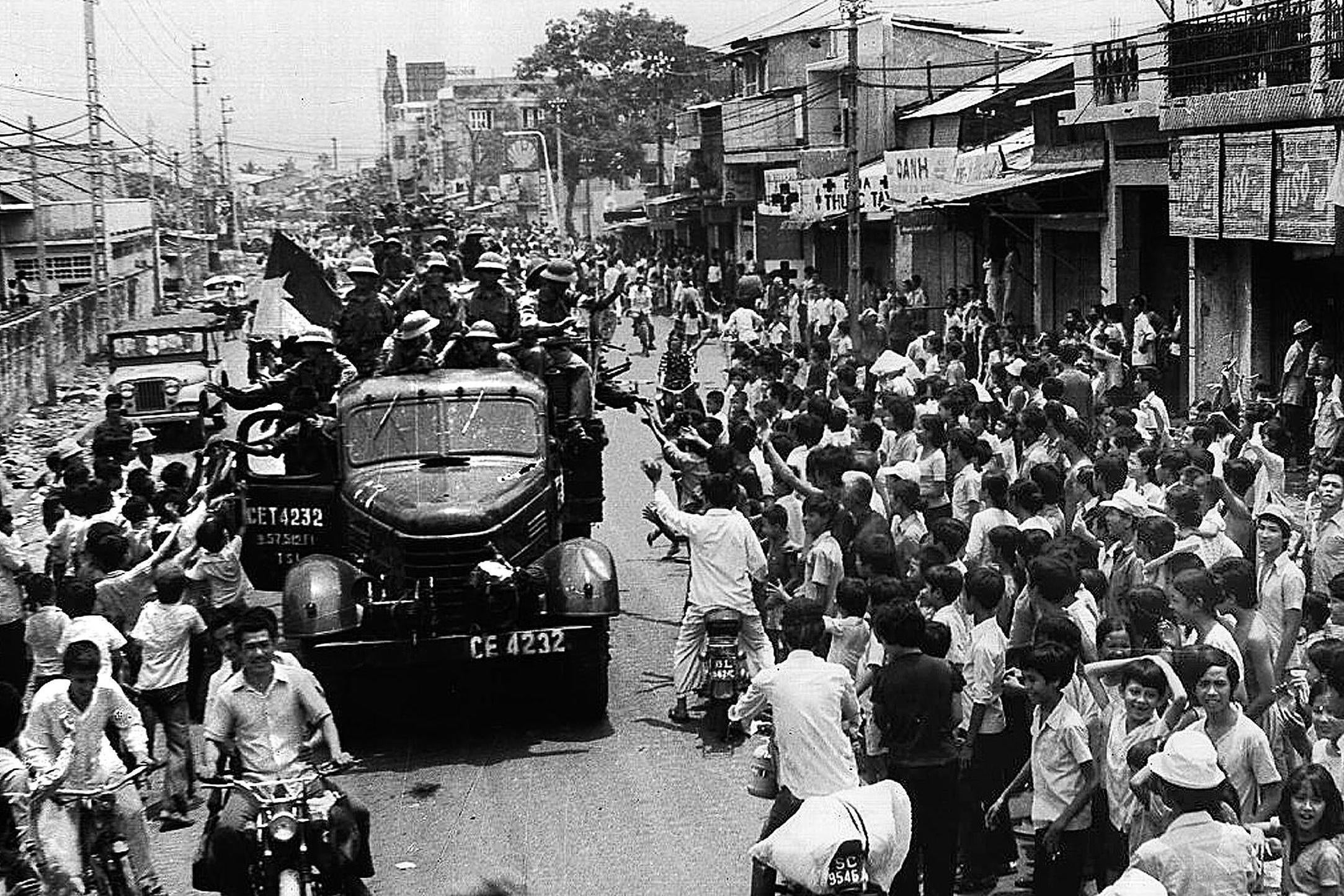

Think of the fall of Saigon, and think of that photograph. The one of people scrambling to the tower atop the United States embassy, desperate to clamber aboard the helicopter perched there as North Vietnamese troops close in on the city. Except, of course, it wasn’t the US embassy, it wasn’t a military helicopter and they weren’t US personnel. But as an image that defines the desperate life-or-death scramble to depart the encircled city following the defeat of the United States and South Vietnam after 20 years of war, it still resonates today.

The photograph was taken 45 years ago today by Hubert van Es, a Dutch photojournalist working for United Press International. The following day Saigon was overrun and the Vietnam War was over. Panic had defined those final days and news reports had emerged of the wretched crush outside the US embassy. The CIA had been scouting rooftops for potential helicopter escape routes and the embassy was indeed selected. Which is probably how the myth grew that the photo was of embassy staff and Vietnamese refugees scrambling their way towards safety. But other sites were pickup points too and Van Es was close by an apartment block at 22 Gia Long Street. Somebody shouted to him that there was a helicopter on top of the apartment building and a snaking line of people climbing their way towards it. The Dutchman began to take photographs.

The Vietnam War was one of the first widely recorded by photojournalism and Es’s photograph is part of an infamous canon that includes Phan Thi Kim Phuc taken by Nick Ut as she ran down the road naked and covered in burning napalm dropped by South Vietnamese planes. Images such as Ut’s ensured that by the time Es’s photograph was taken, public opinion in the US had long since turned against the war. However, as a metaphor for the defeat and panic as the conflict reached its conclusion, it stands alone.

The street chants of “Hey! Hey! LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?” calling out US president Lyndon B Johnson’s support for the war had, by the time of the photograph, been replaced by a “get the folks home” attitude. The photograph shows just how desperate their predicament had become. American citizens in Saigon were rightly terrified of what would almost certainly follow the North Vietnamese victory.

Molly McSmith’s grandfather Harry Maloney was a contractor for an American business based in Saigon. He died four years ago but McSmith, aged 59, who lives in Washington DC, remembers his stories. “He was fortunate, he got out in early April,” she says. “But panic was already spreading. They heard rumours of what would happen to them if the Viet Cong caught them. He talked of American soldiers being strung up and suffocated inside their own skin. Nobody knew what was true and what wasn’t but he didn’t want to wait to find out.” Maloney went by motorcycle to the US embassy where flights were being arranged to the Philippines. “He told me that the scenes outside were mayhem,” says McSmith. “He always said ‘see all those movies about Saigon, and the chaos, and the screaming crowds, and the helicopters. Well it was 50 times worse than that. People were fighting each other to get to the front.’ He saw one guy thrown in front of a bus as others fought to get his papers. He was terrified he wouldn’t be let through, but he had his American passport. Other people weren’t so lucky. What it was like by 29 April I can’t imagine.”

The civil war between the communists in North Vietnam – supported by the Soviet Union and other allies – and the western-backed South had begun in 1955 and while the United States had underwritten the governments of first president Ngo Dinh Diem and then his successor Nguyen Van Thieu in Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, it was only in 1965 that it began committing combat troops to the campaign, along with a handful of other western-bloc nations including South Korea and Australia.

They heard rumours of what would happen to them if the Viet Cong caught them. He talked of American soldiers being strung up and suffocated inside their own skin. Nobody knew what was true and what wasn’t but he didn’t want to wait to find out

It was to become one of the Cold War’s deadliest proxies, ultimately dragging in adjoining Cambodia and Laos. The North using its conventional army, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), in conjunction with the communist-backed Viet Cong, who fought a guerrilla war in the south, made continual progress throughout the long years of the 1960s as America committed more and more personnel (at its peak in April 1968 there were more than half a million in Vietnam) to the conflict. But as the toll of soldiers returning to the United States in body bags grew and the photographs of burning Vietnamese villages and dead and disfigured Vietnamese children spread, any hope the war could be won on the propaganda front at home or on the ground in Vietnam was gone. Official American military involvement ended in 1973 although advisors, CIA operatives and economic support remained in place. It was only a matter of time before the north was victorious.

When the airport at Da Nang had fallen to the PAVN in March 1975, amid chaotic and distressing scenes of US citizens and Vietnamese refugees scrabbling to board full aircraft, then US president Gerald Ford knew the war was lost and that he had but a short time to evacuate all remaining Americans from Vietnam, along with South Vietnamese individuals at risk because of their association with the United States.

As the PAVN’s Spring Offensive brought them ever closer to Saigon, the US began the largest evacuation of its people in its history. The US government was acutely aware of the threats they faced – soldiers who had returned home had spoken of the horrors they had endured while prisoners of the PAVN and rumours spread of mass beheadings and people being burned alive. Intellectuals, businesspeople, Christians… all were on the Viet Cong’s hit list. Nobody wanted to be left behind.

The final hours of evacuation were carried out under Operation Frequent Wind, using only helicopters to skim the city rooftops. It was a fraught task. Anybody who could not get to the pickup sites missed their chance. The radio operators co-ordinating the airlift were unable to fulfil all the anguished requests for evacuation. The pleas, at times, were desperate and would haunt them into old age.

Crowds soon learnt where the helicopters were landing; thousands of refugees rushed to the pickup points. The 31 pilots were ordered to only evacuate Americans at this late stage but many bravely flew in to evacuate South Vietnamese too. In those final hours Frequent Wind removed almost 7,000 people and it was during one of those critical moments that Van Es would take his photo.

Meanwhile, there were many more who would not get out. One of those “unlucky ones” McSmith described was Nguyen Van Khiem (name has been changed). His sister had left Vietnam for the United States two years earlier, to study in Chicago, and he always hoped he would join her. His parents lived in the countryside west of Saigon in territory overrun by the Viet Cong. He never saw them again, although his uncle heard that after postwar “re-education” in a camp they lived out their lives.

Sometimes I wish I had got out. But now life in Vietnam is far removed from those days after the war. We had hardship beyond belief, but truly, I got lucky. Many didn’t

“I was scared for my life when we knew Saigon would fall and the Americans would leave, and we expected reprisals,” he says from Ho Chi Minh City, named after the former president of North Vietnam, and the official name for Saigon today. “I thought if they discovered my sister was in the US they’d think I worked with the Americans. I went to the embassy and the airport but I just couldn’t get near and so I just went back home and waited for the worst. I threw out anything that might mark me out as a supporter of the South Vietnamese or the Americans. Even cigarette wrappings with non-Vietnamese words on them, anything that looked like western goods or food I burnt. Then tanks came down the street. I don’t know which side they were from, I was hiding in the backyard. There was no power or water for a few days and then after all the panic and noise, relative silence. In the end I risked going back to my job as a shipping clerk, and the new owners who turned up seemed to leave me alone. I was lucky. Old friends of my family who had worked for a French company had their house requisitioned and they were taken away to work, presumably in a camp. I know two of them didn’t survive.”

Van Khiem has since visited his sister in Chicago. “Sometimes I wish I had got out,” he says. “But now life in Vietnam is far removed from those days after the war. We had hardship beyond belief, but truly, I got lucky. Many didn’t.”

The US ambassador to South Vietnam at the time, Graham Martin, was one of the last to be evacuated on the early morning of 30 April. In denial, ill-prepared and reluctant to leave (his foster son had died in the fighting earlier in the war), US marines had orders to arrest him if he refused. But for all his shortcomings he managed to persuade the commander of the American Seventh Fleet stationed off the coast of Saigon to remain, even after the city fell as South Vietnamese refugees piled onto any vessel they could and set out for sea. US ships were crammed with those who made it, while aircraft carriers cleared their decks, dumping aircraft into the ocean to allow escaping refugees to land in planes they had managed to board before Saigon airport was overrun.

Mai Thi Ngoc, now 69, was one of those who made her way to the waterfront on the morning of 29 April. She now lives in Los Angeles. “When we got down to the river, there seemed to be no system, no organisation. People were arguing over money, who would take whom and what you could take with you and couldn’t. People were pushing their children onto boats, some of them with labels pinned to their clothing saying ‘Please take care of me, my mother wants me to be a surgeon’. It was heart-wrenching and I still have dreams where I’m running round the wharves, trying to find people I know. It was…” she pauses, then goes on. “It felt… at the time it felt apocalyptical.” Whether her choice of word is prompted by the near-eponymous Marlon Brando movie title is moot. But unconscious or coincidental, to those caught up in the events of that month, that day, and fearing for their lives it must have felt like their world was indeed ending.

In total, 130,000 Vietnamese would escape before Saigon was overrun – 43,000 in the last week alone – removed officially or unofficially on American boats and flights or by their own means. Most were resettled in the US. For those who were left behind and were deemed to have assisted the South Vietnamese government or the Americans – it has been reported that departing embassy staff failed to destroy records and as many as 30,000 were identified from papers found there – life would be cruel. Executions and imprisonment awaited many of them while up to 300,000 would be sent to re-education and hard-labour camps where torture and starvation were commonplace. Those that didn’t die from hunger often succumbed to disease. Some were released when it was deemed that they had atoned for their “imperialism” and had been fully converted into loyal socialist citizens, but many more remained in the camps for two decades or more. It is no wonder that people queued in their thousands to board the helicopters during those final frantic hours.

On the weekend after the Donald Trump-approved assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in early January this year there was a huge spike in online searches in the US for 'draft age'

Look at the photograph again. Its composition is a perfect summation – either by chance or by deft execution – of the panic enveloping the moment. The crowded ladder, the crewman in black trousers with hand out towards the oncoming queue, the helicopter which clearly has capacity for only a fraction of those climbing towards it. Who were they? How many never took off? Well, the crewman was the pilot, OB Harnage, a volunteer, and the person he was reaching for was a young doctor called Thiet-Tan Nguyen. He would be one of around 20 people Harnage took with him as he lifted off, discarding their possessions to reduce weight. On occasion the pilot stood outside his helicopter while flying it so more could fit inside. Considering he knew none of them, he took commendable risks. It was the last trip he would make to Gia Long Street. The vast majority of those in the photograph were left behind.

Had Van Es used a long-focus lens – none was to hand – he would have achieved more detail but the ant-like quality of the chain of desperate humanity would have been diminished. That it was never the US embassy has, given the intervening years, only magnified the story – all of Saigon was in turmoil, not just one small enclave.

Almost 60,000 American soldiers, seamen and airmen died in the Vietnam War. While that is dwarfed by the millions of Vietnamese who also perished, it remains a scar on America today. Thousands flock daily to the Vietnam War Memorial on Washington DC’s National Mall, which lists the names of the dead. Many were conscripts fighting a war on behalf of other people, not least their own government. The collective memory runs deep too; on the weekend after the Donald Trump-approved assassination of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani in early January this year there was a huge spike in online searches in the US for “draft age”.

Vietnam was one of the first wars to be beamed into the homes of the American nation, indeed the whole world, every evening and it has had lasting effects. Despite the fears of those searching online the thought of the US conscripting its young to fight a foreign war in which it had no direct interest seems unthinkable now – whatever one might think of the nation’s unpredictable commander-in-chief.

And what of Vietnam today? While still ostensibly a socialist people’s republic following the communist victory in 1975 and a total restructuring of society along Marxist-Leninist lines, wholesale reforms, similar to those in China, introduced in 1986 have since created a more open, prosperous society. No longer are Vietnamese taking to boats to leave the country as they continued to do until the end of the 1980s. People are now freer to travel and a limited market economy operates. International relations have been re-established with former enemies, including the United States, and Vietnam is a member of the United Nations. Globalisation means young Vietnamese are as interested in the iPhone 11 as they are in their country’s tortured history. Many who fled in 1975 are now returning to visit and in some cases live there.

Other people who lived through the war are long dead, although the photographic and film record ensures the conflict will always remain in the Vietnam’s subconscious hinterland. And while those who took the photographs and made the films were aware they were dispassionately recording history, to be an active bystander in the middle of such horrors means it is impossible to remain emotionally unattached to their subject, for better or for worse. As Van Es said of his photograph: “It was a strange and frightening time. I got 150 bucks for taking that picture. I never resented that but it was worth so much more – from what it was able to show the world. Without photographers and journalists what happened in Vietnam would have never been exposed, and that goes for both sides.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments