Apocalypse Now at 40: Why we will never see the likes of Francis Ford Coppola’s war epic again

While the film was released in the US to mixed reviews, writes Gerard Gilbert, it has since come to define our image of the Vietnam War

Whichever movie wins the Palme d’Or at Cannes this week, it is highly unlikely to have the scale and ambition of Francis Ford Coppola’s three-hour opus Apocalypse Now. Awarded the prize (jointly with Volker Schlondorff’s Tin Drum) 40 years ago in May 1979, some four months before a shorter, two-hour version was released in cinemas, it’s widely considered one of the greatest films of all time.

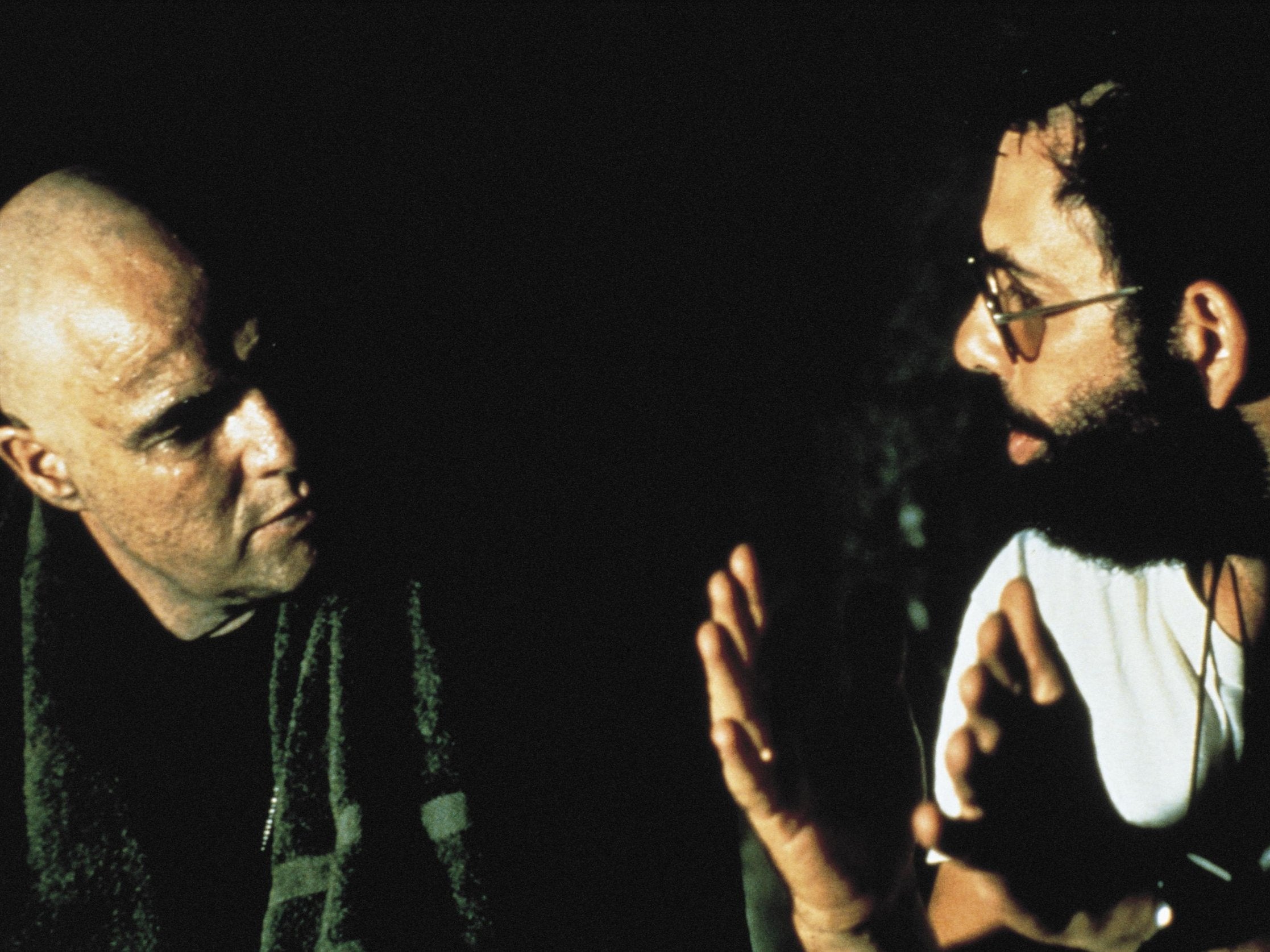

But it wasn’t initially. Indeed, Coppola’s trippy transposing of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to the Gotterdammerung of the Vietnam War in which Martin Sheen’s Captain Willard is dispatched up river to execute Marlon Brando’s rogue Green Beret colonel Kurtz – was met with mixed reviews on its US release. So, although Roger Ebert wrote that the film “achieves greatness not by analysing our experience of Vietnam, but by re-creating, in characters and images, something of that experience”, Frank Rich in Time argued that “while much of the footage is breathtaking, Apocalypse Now is emotionally and intellectually empty”, and Vincent Candy called it “an adventure yarn with delusions of grandeur”.

Others were enraged by Coppola’s press conference at Cannes, in which the director claimed that “My film is not about Vietnam, it is Vietnam”. But in ways I’ll look at later, Coppola’s claim turned out to be oddly prophetic. First, however, a bit on the history of the production.

The best and most immediate account of the logistically mind-boggling five-month shoot in the Philippines during 1976 was written by Coppola’s wife, Eleanor, in her book culled from her diaries and letters, Notes: On the Making of Apocalypse Now. Eleanor Coppola recounts the infamous misfortunes that beset the production, from the typhoon that destroyed the set, Martin Sheen’s heart attack and how Brando turned up overweight and underprepared, as well as her husband’s gradual descent into a nervous breakdown and the near destruction of their marriage. Or as Coppola himself admitted at the Cannes press conference: “Little by little we went insane.”

Notes begins with a quickfire insight into the casting of Brando (Kurtz was also offered to Jack Nicholson and Al Pacino) and Sheen (Willard was turned down by Steve McQueen, James Caan and Robert Redford, while Harvey Keitel was replaced after three days of filming). One can only wonder what Apocalypse Now would have been like with Nicholson as Kurtz and McQueen as Willard, but then movie history is littered with such casting what-ifs.

Having read Notes for the first time recently, I then took another look at the film itself, only my third viewing in 40 years, and the first for a very long time indeed. This was a friend’s DVD of the 2001 Redux version, in which Coppola had added key scenes cut from the original theatrical release – the ones where the boat crew come across the Playboy “bunnies”, now stranded in the jungle, and where they stumble across a plantation owned by defiant French colonialists. Not having seen these before, I feel the studio was right to omit them; they bog the movie down considerably, making it feel far more self-indulgent than it already was.

The film’s opening sequence is still awe-inspiring, the line of palm trees being criss-crossed in slow motion by helicopters before bursting into flames while Jim Morrison sings the doomy Doors dirge “The End”. And I still love the way in which the chopper blades merge into the ceiling fan in Willard’s hotel room (“Saigon… s**t. I’m still only in Saigon”). In Eleanor Coppola’s diary entry for the shooting of this scene, Martin Sheen was purposively a bit drunk, cutting his hand on that mirror after accidentally punching it while making some martial-arts moves.

I first watched Apocalypse Now as a student in Liverpool, where, just before the lights went down, a phalanx of young people ran down the aisle dressed as Vietnamese peasants and plonked themselves in the front row. Was this some sort of protest against the almost complete lack of Vietnamese characters or perspective in the movie, or just the sort of undergraduate lark that would now be frowned upon (or worse) as “cultural appropriation”? I wish I’d asked.

If it had been the former, then their protest would have had a valid point. Apocalypse Now is an entirely one-sided look at the American experience of Vietnam – a civil war (lest it be forgotten) that ended well over two million Vietnamese lives (North and South, military and civilian) against the Americans’ 58,000, and that’s before the long-term effects of the weaponised herbicide Agent Orange kicked in. It could, of course, be argued that the film’s callousness and indifference towards “Charlie” (the Viet Cong) and the Vietnamese citizens, was deliberate and political – and to a certain extent, that’s how I understood it both then and now. But for others, the jury is still out as to whether Apocalypse Now is an anti-war film, or a pro-war one.

Exhibit A for the prosecution is the movie’s most celebrated scene, when Robert Duvall’s Colonel Kilgore orders a helicopter assault on a coastal village (so that his men can go surfing! Far out, man), their assault accompanied by Wagner’s “The Ride of the Valkyries” blaring from the choppers’ loudspeakers. The scene, which includes Kilgore’s immortal line “I love the smell of napalm in the morning”, was actually a survival from the first (1969) draft of the script, written by John Milius, the arch-reactionary who gave the world Dirty Harry and who later directed the communist-paranoia movie Red Dawn.

Coppola has since made the fair point that it’s virtually impossible to make a war movie that’s entirely anti-war, but I think I can see what he was trying to do with this scene. What’s more troubling, and harks back to the director’s contentious statement at Cannes, is how life then imitates art. “The Ride of the Valkyries” was used in the Iraq War to psych up American troops before the battle for Fallujah in 2004, the marines’ Humvees blaring out the music as they prepared for some of the most intense fighting since Vietnam. And then art imitated life imitating art when the use of amplified Wagner in Iraq was replicated in the Sam Mendes’s 2005 movie Jarhead.

In the minds of those who were never involved (that’s to say, most of us), Apocalypse Now has come to define our image of the Vietnam War much more vividly than other celebrated movies about the conflict: The Deer Hunter, Platoon or Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, the latter filmed in London’s Docklands and feeling about as Indochinese as a multi-storey car park in Croydon.

Earlier this year, Coppola released what would seem to be the definitive version of Apocalypse Now, the so-called Final Cut, still including Redux’s French plantation stopover, a wordy interlude that does slow the action (as well as featuring an opium-infused soft-core sex scene that could have come from the contemporaneous Emmanuelle films of Just Jaekin). The encounter with the French does, however, provide some much-needed political and historical context, the plantation owner claiming that it was the Americans who invented the Viet Minh (the precursors of the Viet Cong) during the Second World War.

What is clear from Coppola’s various edits is that Apocalypse Now is not 40 years old, but 40 years in the making. It has its flaws and Coppola could never find a satisfactory ending however many times he re-arranged the footage because perhaps he has never really worked out what he was trying to say (was Kurtz mad or sane? Was he as resigned to his death as the sacrificial caribou?). But taken as a whole, it’s a bold (verging on insane), original and epic piece of movie-making and, in the age of Netflix and CGI, we shall probably never see its like again. Meanwhile, like the America that was still in its imperial pomp when it became embroiled in Vietnam, Coppola was never quite the same again once he returned from the jungle.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks