The power of political killings

Qasem Soleimani’s killing signals a tearing up of the rulebook and a return to a lawless time where leaders are vulnerable to attack at any moment, writes Patrick Cockburn

At about 2.30pm on 22 June 1922, my mother, Patricia Arbuthnot, then eight years old with long dark hair, was walking with her nanny in Eaton Place in London. This was just off Eaton Square, close to where her parents, Jack and Olive Arbuthnot, were living in a mansion at 42 Grosvenor Place. She later recalled: “I saw an old gentleman in a black coat standing on the steps of one of the great pillared doorways of the houses there, when another man standing below him on the pavement pulled out a gun and shot him. The old gentleman half-turned around and then slowly collapsed. I wasn’t at all frightened, just supremely interested, and stood there watching while the man with the gun and a companion quietly walked away.”

Patricia had just witnessed the assassination by the IRA of field marshal Sir Henry Wilson, until recently chief of the imperial general staff and effective commander of the entire British army. Other accounts relate that he had just got out of a taxi, was walking up the steps of his house at 36 Eaton Place and had his door key in his hand when he was repeatedly shot by a gunman at point-blank range. Born in Ireland, Wilson had been a highly political officer throughout his career, playing a central role in the Curragh Mutiny in 1914, when cavalry officers said they would refuse orders to force Ulster to accept the home rule along with the rest of Ireland. Just prior to his assassination, he had resigned from the army, become a Unionist MP for North Down, and was military adviser to the new Northern Ireland Unionist government at a moment when Protestant mobs were carrying out anti-Catholic pogroms in Belfast that left many dead.

Michael Collins, as the intelligence chief of the IRA, had ordered the killing of Wilson, which was carried out by two IRA leaders in London, Reginald Dunne and Joseph O’Sullivan, both veterans of the Great War. They were captured minutes after the shooting. By then, my mother and her nanny had returned to her home in Grosvenor Place, where Patricia told everybody about the exciting event that she had just seen. Nobody believed a word she said and accused her of making things up. “I was told, ‘Patricia, you must not tell such lies’,” she later recalled, while her father blamed her obviously imaginary claim about seeing a murder on her too long residence in Ireland at the height of the Irish War of Independence.

Later that day, newspapers arrived at the house with banner headlines confirming everything Patricia had told her parents about the assassination. She had a child’s perfect memory of what she had seen and calmly contradicted newspaper stories of a heroic milkman who had supposedly pursued the killers, hurling milk bottles at them. She said that, on the contrary, they had walked away, her precise recollection of events further alarming her father, who mistakenly thought she might be the only eyewitness. “Now, Patricia,” he told her. “You must never, never, never tell anybody about what you have seen. Not anybody, or the most terrible things will happen to you.”

In practice, she was never in any danger because other people were also witnesses and Dunne and O’Sullivan had been detained soon after the killing. At their trial, the jury found them guilty after three minutes of deliberation. Dunne said that he had fought in the British army for the principle of self-determination “for which this country [the UK] stood. Those principles I found as were not applied to my own country.” He and O’Sullivan were hanged soon afterwards.

The year 1922 was a dangerous one for political leaders everywhere in a Europe still shattered by the Great War. On 24 June, two days after the killing of Wilson in Eaton Place, a right-wing gunman shot dead the German foreign minister Walter Rathenau in Berlin. He was targeted because was Jewish, a liberal and deemed by the far right to be over-conciliatory towards the victorious allied powers. In August, Collins was himself killed in an ambush in West Cork by IRA-men who opposed the terms of the peace treaty with the British government that he had signed.

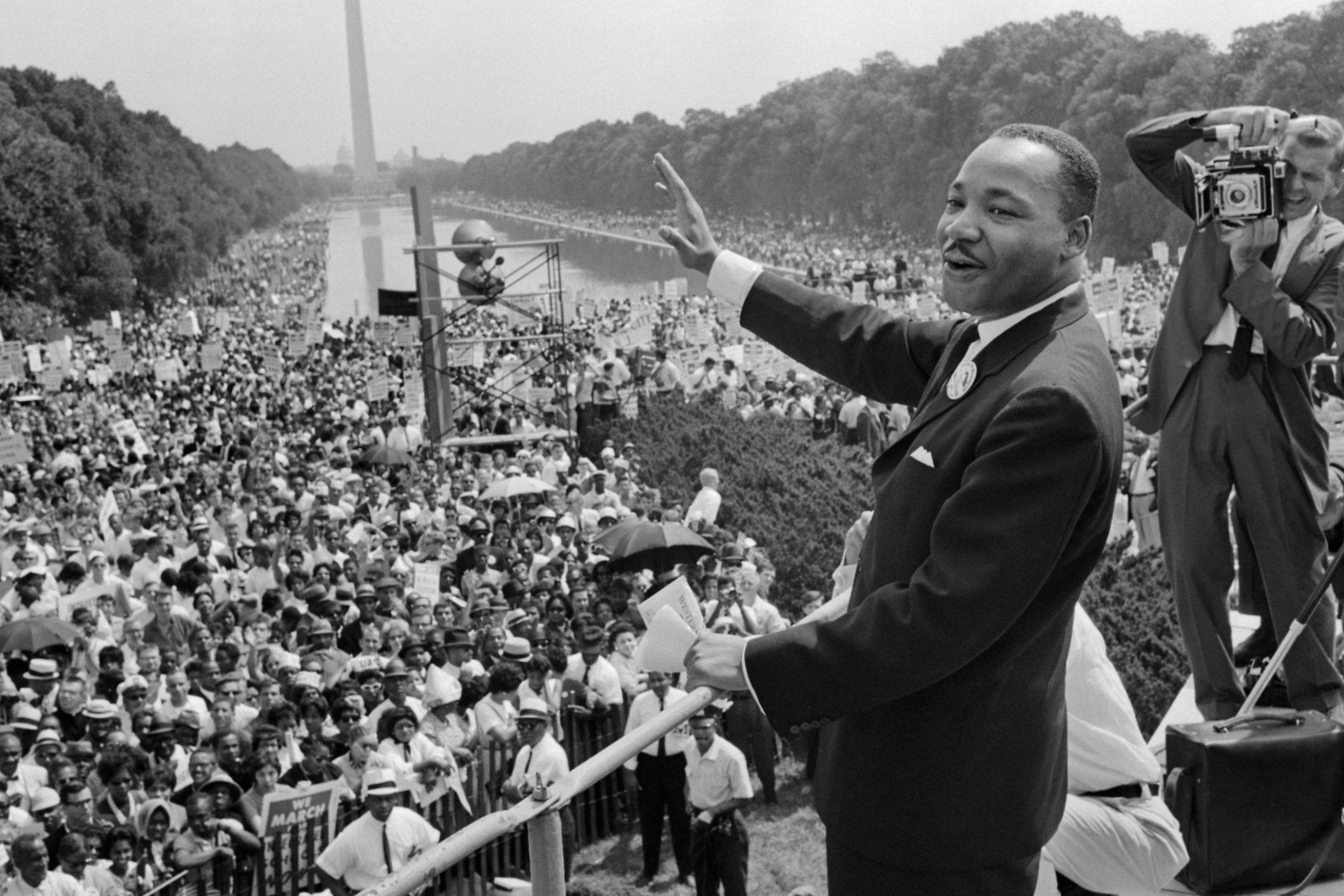

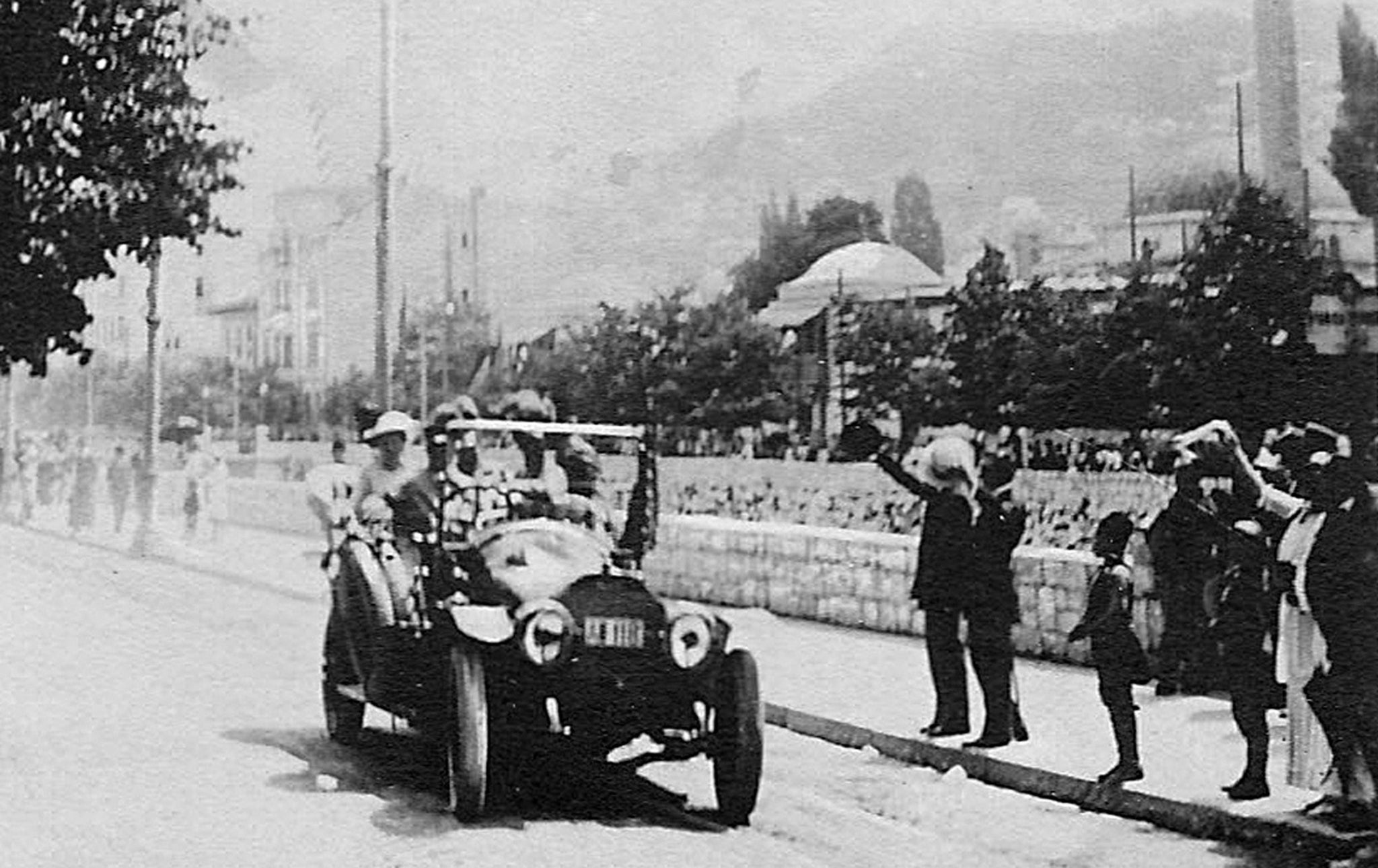

The assassination of monarchs, political leaders and military commanders has traditionally provided convenient punctuation marks in historical narratives, their physical elimination used to denote the beginning or end of an era. School examination papers would ask, for instance, if the shooting of the Habsburg Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, was “the occasion or the cause of the First World War”. The correct answer was a bit of both, though most of those being examined went on to say that probably the war would have happened anyway. Some assassinations, such as that of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, were of undoubted significance and post-Civil War America might have been a better place if he had lived. Others assassinations, like that of President Kennedy in Dallas in 1963, probably had less long-term impact than seemed likely at the time of the shooting. Some political killings, such as that of Martin Luther King in 1968, turned the victims into martyrs, their influence enhanced and sanctified by the circumstances of their deaths. In other cases, like that of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, who was assassinated by soldiers taking part in a military parade in 1981, their deaths seem to have changed very little. Frequently, as with the shooting of Field Marshall Wilson, the violent deaths of people important in their day dominated the news for a short period and they were then forgotten.

Sceptics who downplay the importance of individual leaders in history are similarly prone to conclude that their violent deaths were of marginal influence. This is often correct, but leaders or the absence of leaders may yet be the crucial factor determining the outcome of some struggle or crisis.

I was in Israel in 1995 when a radical right-winger, called Yigal Amir, who was opposed to any accommodation with the Palestinians under the Oslo Accords, shot dead the prime minister Yitzhak Rabin at the end of a peace rally in Tel Aviv. Probably the disparity in power between the Israelis and the Palestinians was so great that the Oslo peace agreement was always doomed, but the death of Rabin was a decisive turning point in more ways than one. It opened the way for Benjamin Netanyahu to win an election the following year and start the first of many terms as prime minister, shifting Israel progressively away from any prospect of an accord with the Palestinians. A broader consequence of the assassination was that Netanyahu became the first of the populist-nationalist politicians who have since taken power all over the world.

Sceptics who downplay the importance of individual leaders in history are similarly prone to conclude that their violent deaths were of marginal influence. This is often correct, but leaders or the absence of leaders may yet be the crucial factor determining the outcome of some struggle or crisis

Assassinations down the centuries differ in method and motivation and have been most common in times of great ideological or religious division. Sometimes the killing is the work of a single professionally skilful, highly motivated assassin, such as the former US marine sniper Lee Harvey Oswald. Sometimes, it is the work of a shadowy intelligence agency and its proxies who seek to cover their tracks like the men who blew up former Lebanese prime minister Rafic Hariri in Beirut in 2005.

Governments and their intelligence agencies may often have been the hidden hand which covertly organised an assassination, but they usually try to conceal their responsibility. To this day it is unclear just how much the Serbian government as a whole knew about what Gavrilo Princip was planning to do in Sarajevo, though ignorance does not quite get them off the hook because governments understandably prefer not to know what their own security services are up to.

But the state-sponsored assassination of the Iranian major general Qasem Soleimani by a US drone at Baghdad International Airport on 3 January was not like that. President Trump said he had ordered it because Soleimani posed an imminent threat to American embassies, though there was no evidence for this. What was new was the killing by one government of a senior official of another government on the sovereign territory of a third government. By ordering it, Trump had torn up the old rules governing international behaviour and reverted to a more primitive and lawless norm when government leaders were vulnerable to attack at any moment.

Openly declared extra-judicial killings by states have become more feasible because of technological developments and their justification is easier because government PR campaigns are more skilful than they used to be in demonising targeted leaders. In the case of Soleimani, the demonisation was retrospective after he was killed and ignored the extended periods when the US was cooperating with him in Iraq, in effect jointly choosing presidents and prime ministers. In the aftermath of his death, a compliant international media focused solely on Soleimani as an enemy with “American blood on his hands”.

It is primarily technological advances that have convinced governments, and above all the US government, that remotely controlled precision-guided weapons enable them to destroy their enemies with impunity. Drones have long been used to eliminate local Taliban leaders in Afghanistan and Pakistan or al-Qaeda leaders in Yemen, so it was probably only a matter of time before they were used to kill the senior officials of a hostile power.

The use of unmanned aircraft makes their use politically attractive because there will be no direct American casualties. Because they are so accurate, striking within a few feet of the target, the chances of failure seem low. The dream of using unmanned aircraft has a long history stretching back to the First World War and the word “drone”, used in this context, dates from 1936 when it was first employed by two scientists in the US navy. But it is only in the last couple of decades that they have been used in large numbers in Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Syria to strike unsuspecting enemies.

A problem is that accuracy is not enough unless there is correct intelligence about the target, and this is often unavailable or mistaken – as a number of wedding parties in Afghanistan and Yemen have found to their cost. Even the successful killing of an enemy commander does not necessarily produce the beneficial result expected because his successor may be more competent and energetic. Precision bombing in Iraq enabled the US to kill Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the founder of al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) in 2006, and his two successors in 2010. But this did not stop AQI, now called Isis, from seizing much of western Iraq and eastern Syria four years later. On the contrary, assassination campaigns tend to fuel a Darwinian process whereby it is the ablest and most competent of those targeted who survive and fight on.

The assassination of Soleimani was lauded for entirely different reasons by the US and by Iran. The US said he was a monster of evil whose activities had contributed to the death of 600 US soldiers, while the Iranians portrayed him as a warrior-martyr who died for his faith and his country. Neither had an interest in admitting that by the time of his death that his strategy in Iraq was not only bankrupt but counter-productive. By orchestrating the violent repression of street protests over social and economic grievances in Iraq, he had unwittingly turned them into something close to a mass uprising by a Shia community that had been previously favourable to Iran.

US presidents, Barack Obama as well as Donald Trump, were attracted by the idea that the US had a monopoly in the Gulf area of precision-guided drones and missiles. As in Hilaire Belloc’s classic rhyme, it appeared that, when all was said and done, that we had “got the Maxim gun and they had not”.

But this monopoly has now been ended. Iran demonstrated this when its drones and missiles temporarily halved Saudi Aramco’s oil output by pinpoint attacks on Abqaiq and al-Khurais oil facilities on 14 September. Houthi rebels in Yemen claimed responsibility, but were disbelieved because the attack appeared to be above their technical capabilities. But this week the Houthis used drones and missiles at a mosque in Marib province in Yemen that killed at least 83 government soldiers, according to the local hospital.

These attacks were directed at buildings and equipment which they hit with great accuracy, but they could have targeted individuals. In other words, a high-tech assassination, like that of Soleimani, is now within the capacity of many countries and paramilitary groups. I was in Baghdad in September, soon after the drone attacks on Saudi Arabia, and I found that the pro-Iranian paramilitary leaders were very excited by the idea that irregular warfare was changing to their benefit. One of them, Abu Alaa al-Walai, the leader of Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada, told me that “we are working day and night to develop drones that can be put together in a living room”. The assassination of Soleimani will have many imitators.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks