The absurdity of owning moors and mountains

Kinder Scout is the highest point of the Peak District. Today it’s quite easy to walk to the top but it hasn’t always been that way. David Barnett tells the story of the famous mass trespass protest

If the weather is fine this weekend, you might decide to go for a walk in the countryside. That you can even do this is mostly thanks to the actions of a scrappy mob of young, working class communists who carried out one of the most important acts of civil disobedience in British history and helped open up the countryside for all of us.

It happened 90 years ago at Kinder Scout, the highest point of the Peak District and a popular destination for walkers. Sitting between Manchester and Sheffield and above the Midlands, it is a vantage point from which you can see – on the clearest days – as far as the peaks of Snowdonia in Wales.

Those who make their way up Kinder Scout for a walk, ramble or hike this summer might well take for granted their right to do so. But it is quite literally a hard-fought one, and something that is as precarious now as it has ever been.

In 1932, Kinder Scout and the surrounding land was owned by the Duke of Devonshire. It hadn’t always been the case; large swathes of what had formerly been common land had been put into private ownership by the various enclosures acts which date back to the 17th century. In many ways, these acts protected and formalised the creation and protection of farmland, but they also allowed the wealthy to essentially lay claim to whatever they fancied, be that a moor or mountain.

After the First World War, and through the 1920s, increased social mobility and improved public transport meant that more and more people wanted to get out of the cities and into the countryside. In the shadow of Kinder Scout, the village of Hayfield, Derbyshire, was a popular destination – especially for mill workers from Manchester and Sheffield wanting to spend their days off in clean, fresh air.

On average, there were around 5,000 visitors to Hayfield at weekends, and the Easter Weekend of 1930 saw 14,000 day tickets sold to take travellers there by steam train.

For the best part of six decades, long negotiations had taken place between the landowners and various bodies such as the Ramblers’ Association to allow access to the land for visitors.

In 1876 the Hayfield and Kinder Scout Ancient Footpaths Association was formed to fight footpath closures across what was once common land. By 1894, the association – led by Manchester radical Richard Pankhurst, husband to Emmeline Pankhurst, one of the leading lights of the suffragette movement – successfully fought the attempted closure of the Snake Path ancient right of way.

So, it was Hayfield that became the scene for what would become known as the Kinder Scout Mass Trespass in 1932 – a deliberate, planned act of civil disobedience that was aimed at opening up the countryside for all, and wrestling control away from the landowners who had decided that it was theirs. And it was not led by a genteel group of ramblers in plus fours and walking boots, but by a contingent of teenage communists from Manchester.

Police had tried to stop some coming through at various stations along the way, but Rothman had cycled all the way there from Manchester to avoid the police attention

Dave Toft is chair of the Hayfield Kinder Trespass Group, which this weekend is organising a series of events to mark the 90th anniversary of the Kinder Mass Trespass. The members of the Young Communist League had often come up to Hayfield and Kinder Scout for camps, where they would hold discussions and debates and, very often, fall foul of the gamekeepers who were patrolling the land on behalf of its owner, the Duke of Devonshire.

“They would go off into the moors and trespass on the land and get manhandled off it by the gamekeepers,” says Toft. “And they sat down and said, ‘We should do something about this. What would we do if this was back in Manchester? We’d hold a demonstration.’ So that’s what they decided to do on Kinder Scout.”

The ringleader was Benny Rothman, from Manchester’s Cheetham Hill, and with his compatriots, including Jimmy Miller, who would later change his name to Ewan MacColl and achieve renown as an activist and folk singer, set about organising the event.

Leaflets were distributed across Manchester and coverage obtained thanks to Miller, who acted as press secretary, in the Manchester Guardian and Manchester Evening News. The establishment took notice of what was going on and took it seriously. On 24 April, all police leave across Derbyshire was cancelled in anticipation of the event.

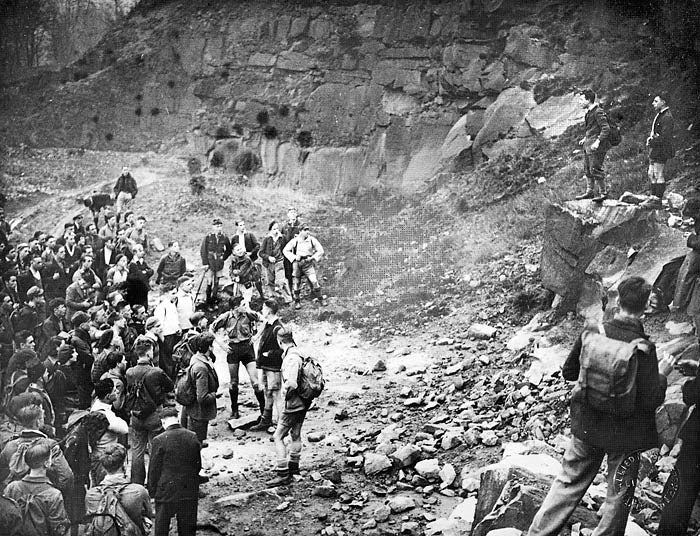

Around 600 protesters arrived from Manchester, with more from Sheffield and Derbyshire. Police had tried to stop some coming through at various stations along the way, but Rothman had cycled all the way there from Manchester to avoid the police attention.

The police blocked the routes to the walking paths up to Kinder Scout, but the protesters broke through the lines, and singing The Red Flag and the Internationale they marched to the foot of Kinder, where Rothman and others addressed them and drove home their right to access the countryside, then they marched up the hill.

Toft says there was no real violence, just a few scuffles with the Duke of Devonshire’s gamekeepers, armed with sticks, who tried to prevent them marching on the land. And the protest might have been of brief interest to the general public and then perhaps forgotten, but for the trial that followed.

Police made five arrests in Hayfield, and when they came to court, they were charged with a variety of offences including breach of the peace and even riot – there wasn’t an offence of trespass on the statute books. A jury of what Toft calls, “retired colonels and local landowners” found the five guilty and they were given custodial sentences of up to six month’s hard labour.

But the trial had attracted national interest and the sentences provoked outrage from not just the liberal chattering classes but from ordinary people as well, who recognised that these protesters weren’t rabble-rousing communists but simply exercising their right to do what every person in the UK should be able to do – walk in the countryside.

“Most of them were in their late teens,” says Toft. “They’d all left school at 14, and the farce of a trial got a lot of national attention. Initially, the official groups such as the Ramblers Association had been very opposed to the protest because they had their own negotiations going on and thought this was going to spoil the discussions, but they realised when the trial hit the headlines that this was what was exactly needed to get public sympathy which it did.”

The publicity from the trial and the debate it sparked led directly to the creation in 1951 of the Peak District National Park, and the handing over of the land by the Duke of Devonshire to essentially public ownership again. The national park was the first of its kind in the UK, and at its centre is Kinder Scout. It is now managed by the National Trust, and 10 million people visit every year.

But its not quite the happy ending that it could be. Because while our right to roam the countryside was, in part, given to us by the Kinder Scout Mass Trespass 90 years ago, it isn’t as set in stone as we might like to believe.

“We perhaps haven’t come as far in 90 years as we might like to think,” says Toft. “Of the United Kingdom, only eight per cent of it is accessible by the public, which I think is quite astonishing, given the amount of open space we have in this country.

“Yes, we made steady progress with the national parks opening, and the Countryside Rights of Way Act (2000) has consolidated gains in access and helped extend it, but we do live in quite dangerous times. When the Kinder Scout protesters were arrested there was no such criminal offence as trespass, but the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill that they’re trying to bring in creates such an offence for the first time, and that’s definitely a step back.”

The pandemic made us realise how great walking is and how access to the countryside is as good for mental health as much as anything

This past weekend there was a raft of events at Hayfield and Kinder Scout to mark the 90th anniversary of the trespass, and present will be the President of the Ramblers Association, one Stuart Maconie, who you might know better as a broadcaster and writer.

Although the Ramblers Association was perhaps a little dubious about the actions of Benny Rothman and the Young Communists League back in 1932, Maconie is in no doubt at all about the importance of that protest.

“When I took over as president one thing I was keen to do was re-emphasise the fact that we are a campaigning organisation,” he says. “Yes, walking is great for fitness, wellbeing, and mental health, but we must also remember that the roots of access to the countryside are in dissent by some commies from Manchester and Sheffield.

“This lot didn’t just set off for a stroll, they deliberately organised a mass disobedience event because they’d had enough of being bossed around and chucked off land they felt they had an absolute right to be on.

“The thing we have to remember is that nothing in Britain we get as a right or privilege has ever been gained by asking politely for it. Open access is one of those things, and it has been hard-won by sustained campaigning and events such as the Kinder Mass Trespass.”

Maconie is passionate about our right to get out into the countryside and agrees with Toft that it can be a bit precarious, pointing to incidents in the first lockdown during the pandemic in 2020. We were all encouraged to get out and exercise once a day, and that led to people taking to the countryside for their prescribed walks. But then we also saw that landowners were barring footpaths and putting up no entry signs when there was no justification for it.

“The minute people had the feeblest excuse to start bossing people around again they took the chance,” says Maconie. “Signs went up telling people to go home, footpaths were closed off, the mask slipped completely as soon as they had the chance, backed up by the government and the police. The bloody landowners were at it again.” He pauses. “I should say this is not official Ramblers policy but my own personal view.”

Toft says that lockdown also highlighted tensions between the rural and urban communities, and that Derbyshire police were the first to use drones to take footage of a couple walking on the moors when they weren’t supposed to be there. “It has brought up lots of issues and shows us that people don’t have the free access all the time that they think they do,” he says.

“It took the merest thing for people to say, ‘we can stop these oiks coming on our land again’,” says Maconie. “And that made us realise that the thing we take for granted was quite precious because it can be taken away from us.

“Some of the crackdowns we saw during lockdown were very heavy-handed and over the top, such as police threatening to arrest a couple of women with a flask of coffee when champagne corks were popping in Downing Street, as we now know.

“It was the same sort of motivation that the gamekeepers had on Kinder Scout in 1932. It’s not really farmers, most farmers are brilliant. It’s people who think the public shouldn’t be allowed on their land.

“The whole idea that people can own moors and mountains and places like Kinder Scout is just mad anyway. It’s absurd that some guy not through any hard work but through some accident of birth, some criminality and skulduggery in the 17th century or whatever, can enclose the land, just say, I own this mountain, I own this moor. It’s preposterous.

“And remembering the Kinder Mass Trespass is a way for us to remind ourselves how absurd it is for someone to say they can own that, helps us see what a nonsense that is so we don’t let it happen again.”

For more information go to kindertrespass.org.uk/

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks