‘Over before it had really begun’: The last time Britain was invaded? No, it wasn’t 1066

The last invasion of Britain was more recent than you think and is an astonishing tale of botched plans, bad luck and drunken soldiers, writes David Barnett

When was the last time foreign invaders set foot on British soil?

If you said 1066, when William the Conqueror defeated King Harold at the Battle of Hastings, ushering the age of the Norman conquest of Britain, lose five points.

The last invasion of Britain took place considerably more recently than that… just 225 years ago this week, in fact.

On 22 February 1797, four French warships together carrying a force of 1,400 soldiers sailed into the bay at Fishguard, Pembrokeshire, Wales, intending to conquer England.

They were led by Colonel William Tate, an Irish-American military man who was a veteran of the American War of Independence that had ended 14 years earlier, in a plan masterminded by General Lazare Hoche, who had served during the French Revolutionary Wars. The invasion was to be carried out in support of the Society of United Irishman, which was inspired by the French Revolution and advocated a united Ireland against British rule.

And perhaps the most surprising thing about an actual invasion of Britain is that it was actually very, very… funny. So funny, in fact, that anyone looking for the next big British movie could do a lot worse than take a look at the Fishguard invasion.

For example, bad weather forced the invading fleet to not land at Bristol, as planned, and put the port city to the torch, but to go round a bit further and end up in Cardigan Bay. And the first thing the soldiers did when they landed in Wales was to raid local farms and drink all the booze they could find, rendering them insensible. And to cap it all, a local woman decided to take matters into her own hands and armed herself with a pitchfork to prod a group of drunken French invaders back to their ships from the fields in which they’d collapsed in a drunken heap.

But the rather bawdy comedy of it all aside, the planned invasion was a very real attempt to destabilise the British government and could have actually worked, to some extent, but for the co-incidental presence of British military forces in the area.

Our guide to this astonishing little chapter in British history is Edward Perkins, a local historian and member of the trustees of the organisation dedicated to preserving the memory of this curious invasion.

Edward, 79, has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the incident and has assembled a wealth of information and historical documents that chart the beginnings of the attempt to take over Britain.

The French plan was based on a certain presumption: that when they landed, they would be able to persuade the general population of Britain to rise up against the monarchy

And he says we must go back to the French Revolution to understand the context of the events that led up to the invasion of Fishguard.

Until 1789, of course, France was a monarchy, but rebellion was stirring and in July that year crowds of republican-minded Parisians stormed the Bastille to arm themselves against the French troops moving towards the city to quell the disturbances, and the French Revolution had begun.

When the monarchy was overthrown and the revolutionary government established in 1793, there was much disquiet across the Channel in Britain. It was Britain that made the opening gambit against the new republic that was our nearest neighbour.

In June 1795, British naval and land forces supported a royalist invasion of France at Quiberon Bay. The royalist army landed, met and were defeated by the General Lazare Hoche in command of the revolutionary army. By March 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte had been appointed to control the French army in Italy and the French decided that if they had been able to overthrow the monarchy, then surely the disaffected proles of Britain could be encouraged to do the same.

And this was the basic principle behind the invasion of Fishguard. It began 16 February, when General Lazare Hoche – the man who had fought back the British at Quiberon Bay two years earlier – was put in command of four ships that left Brest loaded up with 1,400 French soldiers.

The plan was to sail up the Bristol Channel, burn the city to the ground, and then proceed to London.

Edward says: “Obviously an army of 1,400 men was not going to be able to march on London and take over the country, even back then. The French plan was based on a certain presumption: that when they landed, they would be able to persuade the general population of Britain to rise up against the monarchy and join the French army’s attack on London.”

Even before the invading force had to deal with that small matter, things started to go wrong. They’d waited at Brest for two days for the right winds, and when they set off the weather changed, making it impossible to sail up the Bristol Channel. But the French had a Plan B: sail a little further around the Pembrokeshire coastline and land in Cardigan Bay.

Edward says: “On Wednesday February 22 the French ships appeared off Fishguard. They’d been sighted that morning by Captain Thomas Williams at St Davids. The ships were flying British flags but Captain Thomas recognised them as French, and sent word to Fishguard that they were heading up the coast.”

At Fishguard there was a fort and it fired a blank cannon shot as soon as the invading force came into view. It’s here that a pivotal event occurred. According to Edward, the combined might of the four ships’ armaments could have overwhelmed the fort’s fire-power, and they could have landed at the port, resulting in probably bloody fighting and a huge loss of life.

But put off by the shot across their bows, the French ships sailed on a little, putting in at Carreg Gwastad, just two miles west.

It would have been dark and very late into the night when the ships unloaded their men and equipment, says Edward, adding: “There they unloaded their forces, stores, ammunition, etc, and marched inland reaching the homestead of Trehowell Farm. It is likely most of this work was done in darkness. At the point chosen for disembarkment, there is no steep cliff only a grassy slope running down to the rocks at the edge of the sea. Equally, with small boats and in darkness it must have been a difficult operation.”

The 1,400 soldiers and almost 1,000 crew across the four ships had been cooped up for six days since they had embarked at Brest. They were ready for a fight, and ready for something else as well: booze.

Edward says: “It is recorded that in landing at this point, they carried 47 barrels of gunpowder, 13 boxes of grenades and 2,000 other arms, including muskets, cutlasses, etc, from the ships to their headquarters. The headquarters were located at Trehowell Farm, approximately one mile from the landing place, and at that time in the ownership and occupation of John Mortimer.

“After a night spent in the open, on Thursday 23 February some of the troops penetrated inland occupying Garnwnda and Garn Gelli overlooking Fishguard Bay, and Goodwick and Fishguard areas. There are reports that some of the French troops penetrated down as far as the Goodwick St Davids road close to Manorowen and certainly laid in wait in ambush for British forces on the small roadway leading from Goodwick to Garn Gelli.

“The majority of the French forces were engaged in searching for food supplies on the neighbouring farms of the Pencaer (Strumble Head) Peninsular. The historical records show that somewhere between 40 and 50 different farms, cottages and houses were raided in the search for foodstuffs. In addition to food supplies the French found considerable supplies of beer, wine and spirits. As a result by the afternoon of Thursday 23 February, this military force was basically in an uncontrollable situation with a large number intoxicated from the supplies which they had found and refusing to obey their officers.”

The opposing British forces were lined up not only on Goodwick Sands but on surrounding areas and took control of the French forces and marched them to Haverfordwest

Where were the British troops at this point? As of Thursday morning, the only British forces near Fishguard were the Fishguard Fencibles militia, under the command of Lieutenant Col Knox in two divisions at Fishguard and Newport and totalling about 300 men who were assembling that morning.

The military commander in chief for west Wales was Lord Milford of Picton Castle as lord lieutenant, but by Thursday morning he had delegated his authority to John Campbell, Lord Cawdor of Stackpole, who had under his command a Yeomanry Company of 43 troopers who assembled on Thursday morning and marched towards Fishguard.

Crucially, says Edward, the co-incidental presence in Haverfordwest of Lieutenant Col Colby a regular soldier with 100 troops from the Cardigan militia that might have swung the course of the invasion – on Wednesday evening into Thursday morning he was organising the collection of available forces to march on Fishguard, a force of some 600 men.

There’s a story that Edward says probably is a little apocryphal, but which is lovely nonetheless. He says: “Among the traditions and stories of the French Invasion is the part possibly played by the Welsh ladies of Fishguard, dressing up in red cloaks, and who were mistaken for British regular troops. This story has been heavily publicised over the years, but there is little historical evidence to show that it took place.”

One story that has been stood up, though, is that one local woman, Jemima Nicholas, found a group of a dozen drunk French soldiers in a field, took up a pitchfork, and prodded them up their backsides until all the way to Fishguard, where they were formally captured.

There was no pitched battle, though. Late on the Thursday afternoon some skirmishing took place between French and local forces, and it is thought that in total two soldiers died, but there was no major engagement. Most of the French forces were incapable of any direct action because they’d essentially drunk Fishguard dry and refused to obey their officer’s orders.

And the presumption that the local people would rise up against the British government and march on London alongside the invading French force proved to be something of a major disappointment to the invaders.

Col Tate decided that as he had no control over his soldiers they had no choice but to surrender. Edward says: “As a result, negotiations took place and eventually late at night a surrender was agreed. It was reported that the following morning Lord Cawdor visited the French camp and confirmation of a surrender agreement was made, although no copy of the documents can be found today.

“On Friday 24 February, in the early afternoon the French forces marched from Trehowell Farm to Goodwick, lined up on Goodwick Sands and laid down their arms. The opposing British forces were lined up not only on Goodwick Sands but on surrounding areas and took control of the French forces and marched them to Haverfordwest. There they were imprisoned in various places including St Marys’ church and in due course moved on to other prison locations, mostly in the south of England.”

And the last invasion of Britain was over, before it had really begun.

“It’s a great story,” says Edward. “And a hugely important chapter in British history as the last time a foreign invading force put boots on British soil.”

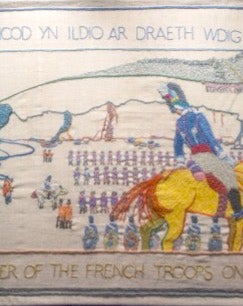

Not William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings, as many people presume. But in common with the Norman Conquest, which has the Bayeaux Tapestry to tell the story, the Fishguard invasion has a similar record, though much more recent.

The Last Invasion Embroidered Tapestry is 100ft long and took four years to complete, and is now housed in a permanent exhibition in Fishguard Town Hall.

The Tapestry was designed by Elizabeth Cramp and she led a team of 80 local people who embroidered it, beginning in 1993 and completing it in 1997, the 200th anniversary of the invasion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks