What is it we all like about impressions?

When Jamie Costa’s uncanny performance as Robin Williams in a short film went viral, it put the venerable and ever-evolving art of mimicry and impression back under the spotlight. David Barnett reports

What self-respecting child of the 1970s can truly say that they never once stood, at a family gathering or holiday camp talent show, with a wide-eyed, nonplussed expression, knock-knees, and uttered in a slightly camp voice the immortal words: “Oooh, Betty, the cat done a whoopsie on the carpet”?

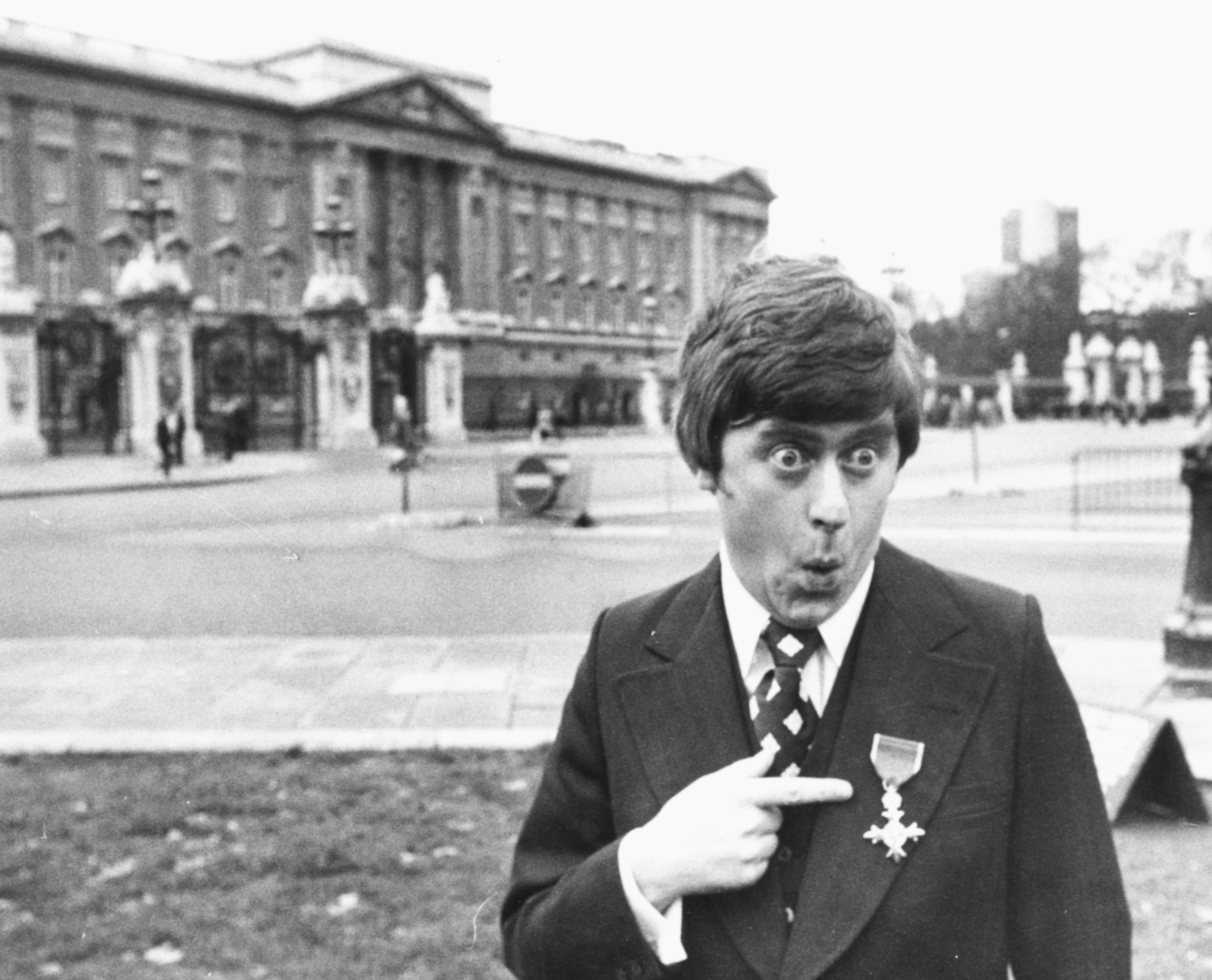

Michael Crawford’s (with hindsight) worryingly childlike Frank Spencer, from the TV comedy series Some Mothers Do ’Ave ’Em, was ripe for “taking off” as my mother would ’ave it. His gormless expression was easy to ape, everyone could do his voice, and he had a simple catchphrase.

Except, according to the website TV Tropes, Frank Spencer never said either “Ooh, Betty” nor even alluded to the cat’s indoor toilet habits. What we were all doing as kids was an impression of an impression of Frank Spencer.

Because if every schoolyard played host to a Frank Spencer impression, so did every Tuesday night at the local working men’s club, every TV talent show, even every now and then at the London Palladium. In those heady decades from the 1960s to the 1980s, comedy was king and the gambolling jester at the court of King Fun was the impressionist.

If you’d have asked me before the age of 20 to name an artist from the impressionist school I’d have probably said Rory Bremner, Janet Brown, or, the daddy of them all, Mike Yarwood. It’s Yarwood who is attributed to giving Frank Spencer the catchphrase he never had, with the beret-wearing idiot savant one of Yarwood’s staples alongside Peter Falk’s shabby detective Columbo, expansive, arm-waving boffin Magnus Pike, up’n’under Rugby League commentator Eddie Wareing, and current affairs presenter Robin Day, as well as a host of then contemporary politicians such as Ted Heath.

Yarwood, now 80, was born in Bredbury, near Stockport, and started his career doing impressions of children’s characters such as Billy Bunter for his schoolmates. He entered a local talent show, which he didn’t win, but the organiser was so impressed he offered him a slot at a club. He then went on to become a warm-up man for the BBC’s Comedy Bandbox show, which saw him invited to perform on the show himself, leading to an appearance in 1965 on Sunday Night at the London Palladium, from where Yarwood went stratospheric. He got his own show and his 1977 Christmas special drew an audience of 21.4 million – still one of the most-watched TV programmes in British television history.

The whole idea of impressions is… well, is it funny? If you think Michael Crawford playing Frank Spencer is funny in a sitcom framework, why is it funny to see Mike Yarwood playing Michael Crawford playing Frank Spencer? Everybody did a Frank Spencer, just as everyone did a take of comic magician Tommy Cooper, donning a fez and shaking their hands in front of them and slurring, “Juss like ’at”. The hand movement also doubled nicely for a Max Bygraves impression, which was essentially Tommy Cooper without the fez and replacing the catchphrase with, “I wanna tell you a story”. Presumably, many impressionists who did the clubs and TV shows in the 1970s and 1980s would like to excise their cigar waggling, “Now then, now then” Jimmy Saviles from their back catalogue.

“Impressionists are maybe scrutinised more than any other comedic performer,” says Keegan Wilson. “It’s not so much about how funny or not they are, but how good is their impression? Do they look and sound just like who they are impersonating?”

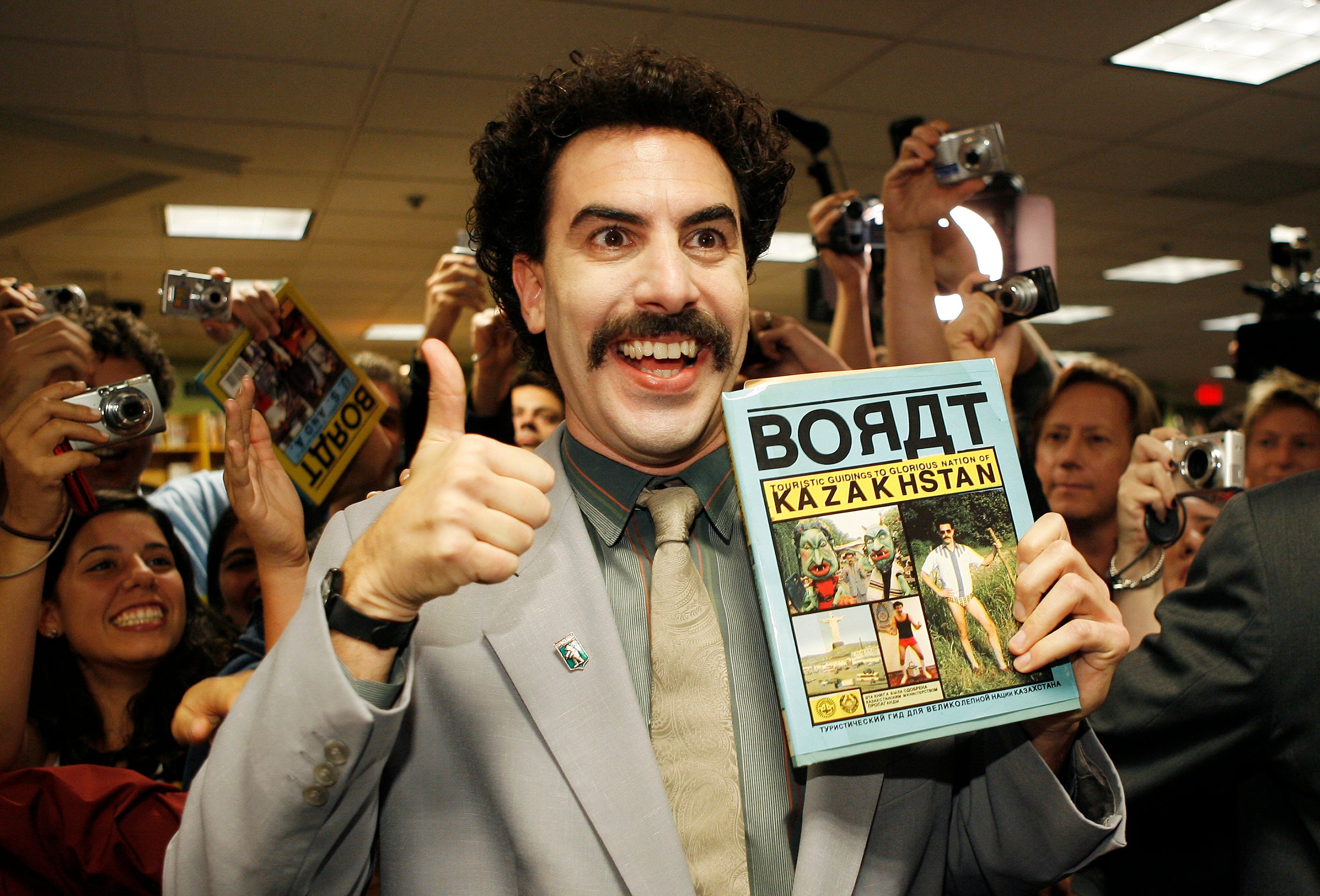

Take Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat and Ali G. In my opinion, these are pioneering characters, but essentially they are impressions of fictitious characters created by him and his writing team

Wilson is a comedy writer, scholar and formereditor of the quite excellent humorous magazine Pop Cult, which is now sadly doing an impression of an extinct thing, maybe a dodo. And, he says, the roots of impressionism were not originally just to entertain and amuse, but to mock and ridicule.

“Impersonating people for reasons of comedy has a long history in Europe,” he says. “In ancient Greece mimics would entertain crowds by ridiculing known people through mime. Jesters date back to Roman times, and part of their comedic weaponry, as was the case when the tradition was revived in royal courts around Europe during the renaissance, was ‘doing impressions’.

“Imitating and exaggerating characteristics of political rivals and enemies and using humour in ways to mock and question their sexuality, intelligence, bravery and authority, would not only have been highly audacious and entertaining, but in those days it would have been an extremely useful function in shaping wider opinion and getting people onside.

“Take Charlie Chaplin’s 1940 portrayal of Hitler in his satire The Great Dictator, or the hilarious animated impression of Osama bin Laden making a terror video in Family Guy, and suddenly the scary enemy doesn’t seem so menacing. Impressions were, and still can be, an immediate and effective form of propaganda.”

In the 1970s and early 1980s, impressions were largely devoid of cruelty. Though they exaggerated the subject’s mannerisms, speech and appearance, it was more of a homage than an attack. Sometimes, as with Lenny Henry’s impression of TV botanist David Bellamy (“Gwapple me gwapenuts,” anyone?) the impersonation was so warm and lovely that it made you feel even fonder towards the person being mimicked.

It wasn’t really until Spitting Image came along in 1984 that the satirical side of impressions returned to those Greek and Roman roots and really began to bite. Can we really include Spitting Image’s rubbery caricatures of politicians and celebrities as impressions? Well the voices were certainly performed by humans, with luminaries of the comedy acting and impressionist fields including Harry Enfield, Rory Bremner, Phil Cool, Steve Coogan, Jon Culshaw, Kate Robbins, Debra Stephenson and many, many more either finding fresh work there or getting their first TV breaks.

Keegan says: “While it was funny to see Yarwood and other impressionists prod the egos of well-known figures, which perhaps reached its zenith with Spitting Image, critics would point out that impressions were repetitive and cruel.”

Alternative comedy, on the rise in the mid to late 1980s, rarely embraced impressionism (though comedy magician Jerry Sadowitz once did a mean – in both senses of the word – take of fellow prestidigitator Paul Daniels, which mainly involved wearing a piece of card bearing the words “Wee Shite” around his neck and talking in an exaggerated high-pitched voice), so the form sort of fell out of favour for much of the 1990s, save for the ever-present Rory Bremner mainly skewering political figures.

TV and movie biopics of real people are nothing new, of course, but there’s been a shift in recent years towards employing the toolbox of impressionism and applying it to an acting role

“A lot of the impressionists I grew up watching on TV, such as Les Dennis and Lenny Henry moved away from doing impressions to pursue other career paths in television,” says Keegan. “Alternative comedy was beginning to explode and it was simply not cool to do impressions. In didn’t fall completely out of fashion, in the 1990s and 2000s the Mike Yarwood style was kept alive by Alistair MacGowan, Ronni Ancona and the cast of Dead Ringers.”

Spitting Image did give a springboard to a lot of comedians who developed a kind of hybrid act that was somewhere between stand-up, impressionism, and acting – creating comedy characters of their own, which was not really anything new, but it certainly became a trend.

Keegan says: “Peter Sellars, was a master of voices and mimicry, giving life on radio and in film to countless well-rounded fictional comedy characters. He could do impressions, sure, but his gift was for picking out traits and quirks of the people he encountered, famous or not, and developing those into his acting roles. In that way he is a massive influence on today’s top comedians.

“Take Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat and Ali G. In my opinion, these are pioneering characters, but essentially they are impressions of fictitious characters created by him and his writing team. In this regard those characters are much like Sellars’ impression of Frenchman Inspector Clouseau. Though it’s the influence of 1970s American ‘song and dance man’ Andy Kaufman, who often took his surreal and confrontational comedy in the forms of various characters into real world to interact with real people, which elevates the quality and audacity of Cohen’s satire and work as a jester to another level.

“Harry Enfield, Paul Whitehouse and Steve Coogan all provided impressions for Spitting Image back in the 1980s. From there they put those acting abilities into creating hugely popular comedy characters that were familiar enough for audiences to identify with and enjoy. They were impersonating human behaviour and traits rather than specific individuals, so their comedy can be appreciated for their craft and observations, and as such their impressions come across as much less cruel and more sophisticated.

“Coogan in The Trip, along with Rob Brydon, is forever playing with the role of impressions and their importance, all the while the pair doing impressions and keeping the watching audience thoroughly entertained. He gives a great sense that this fictionalised version of himself (an impression of himself?) is stigmatised by being an impressionist and creator of characters, as a result he gives off an air of disappointment and a feeling for being underappreciated for his acting. Like Cohen, Brydon and Coogan are exploring new territories for impressionist.

“It’s a fair point Coogan makes. In The Trip Brydon suggests Coogan is doing an impression of Stan Laurel in the film Stan and Ollie. A shaken Coogan denies this and goes on to explain that it is more than an impression, it is studied acting.”

Which brings us really to the state of impressionism in the 2020s, largely not done for laughs but as acting. TV and movie biopics of real people are nothing new, of course, but there’s been a shift in recent years towards employing the toolbox of impressionism and applying it to an acting role more than ever before.

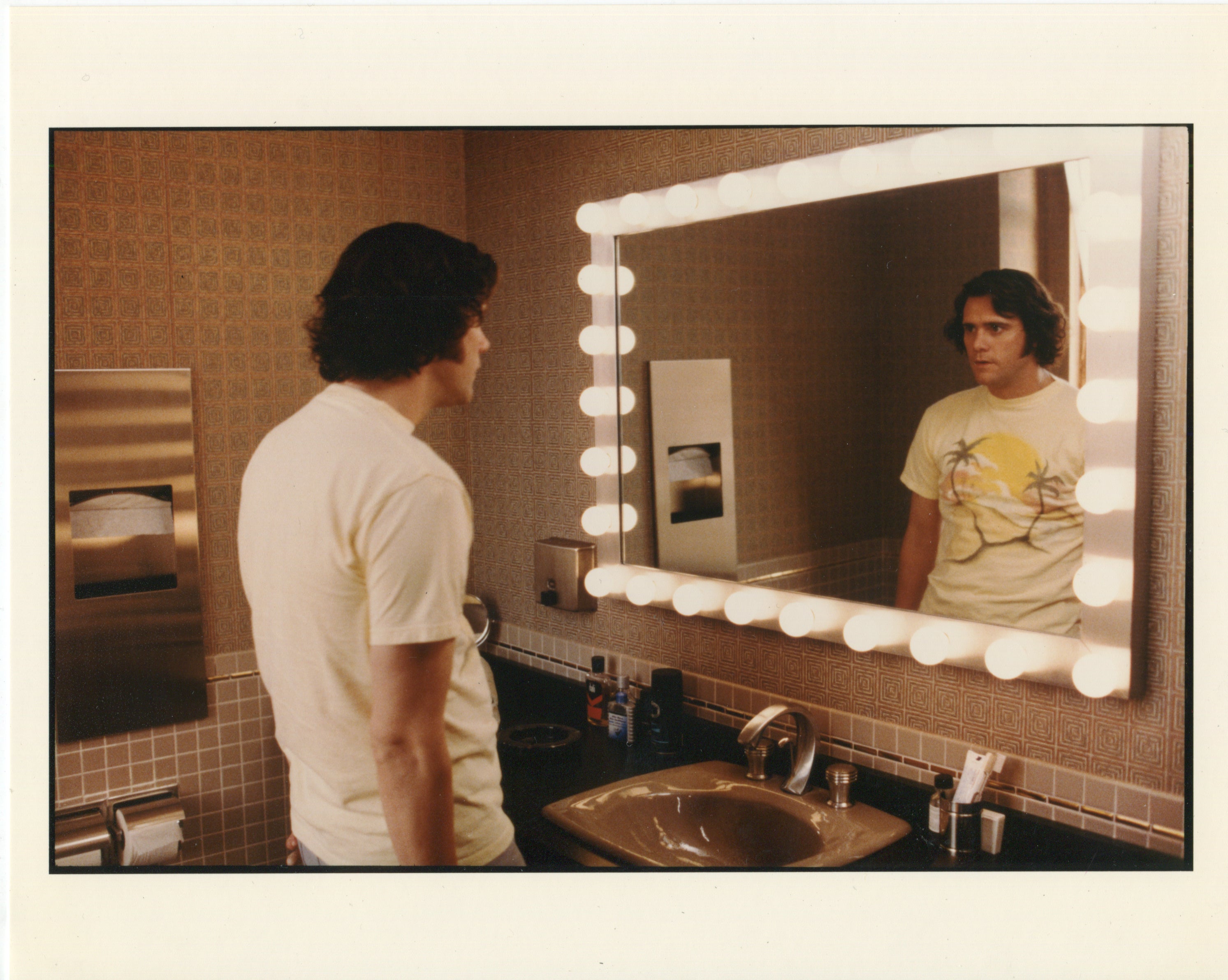

What prompted this piece was the recent viral success of American comedian Jamie Costa’s five-minute YouTube video with Costa acting the part of Robin Williams trying out for his breakthrough TV role in Mork and Mindy. Costa’s note-perfect performance of Williams was uncanny, from the slightest micro-movement of his facial features to his voice to his clothing and his posture.

The video received millions of hits, had fans calling for Costa to star in a full-length movie about Williams, and even had Williams’ family asking for fans not to keep sending links to the footage to them as his performance was so spot-on it was upsetting for them.

As an actor playing a real-life person, you have to get to the root of the person, you have to get to their soul, and give a full, well-rounded interpretation of them

The lines between aping and acting are blurry. Keegan says: “Coogan played Stan Laurel. Jim Carrey, who did impressions as part of his stand-up when he started out, gave a magnificent performance as Andy Kaufman in Man on the Moon. Yet, whenever they do a serious piece they have struggled for credibility from critics. Jamie Costa, who came to prominence doing impressions on YouTube, is joining them as another impressionist playing in film another comedian, Robin Williams. His impression of Williams is stunning and a reminder of what talent we lost with the passing of Robin Williams, but is it acting? I think it is.

“When Charlize Theron played Aileen Wuornos in Monster was she doing an impression? Those giving out Oscars clearly thought she wasn’t, as she scooped up the Best Actress award. So will the Academy recognise Costa when the time comes, or will his talents be easily dismissed as simply copying?”

Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond - Featuring a Very Special, Contractually Obligated Mention of Tony Clifton

Perhaps the king of the character acting impression is Michael Sheen. This truly chameleon-esque Welshman who started out on the stage swiftly carved out a niche for himself with his astonishing ability to inhabit the characters of famous real life people as though putting on a suit. He played Tony Blair in three films: The Deal (2003), The Queen (2003) and Special Relationship (2010). He played British journalist and interviewer David Frost both on stage and screen in Frost/Nixon, and a spine-tingling take of manager Brian Clough during the disastrous Leeds United tenure in The Damned United. He even took the part of the camera-shy Jeremy Dyson, one quarter of the League of Gentlemen writing/acting team, in the 2005 movie The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse.

How does one get under the skin of a real person like that? For Outlander actress Rosie Day, who is playing Cilla Black in the forthcoming drama Epstein, about Beatles manager Brian Epstein, it involved trawling the internet for snippets of footage in the first instance.

While there is lots of video about from Cilla’s later career, the “lorra lorra laughs” Blind Date years, Day is playing a young Cilla, fresh out of school, and had to dig a lot deeper.

Day says: “I’m playing her between the ages of 18 and 24 and there’s not a lot of footage out there, but what there is I studied every single second of it. As an actor playing a real life person, you have to get to the root of the person, you have to get to their soul, and give a full, well-rounded interpretation of them.”

Day would listen to how Cilla spoke – interestingly, in her early days, trying to make a career in show business, she eschewed her native Liverpool accent for something more neutral, though she soon embraced her roots again – and respond to recordings of Cilla speaking, holding a conversation with her. She tracked down people who knew Cilla in the early years and tried out her voice on them, read and re-read her autobiography to pick up turns of phrases.

“Then I would copy her mannerisms, try to work out what felt most like what Cilla would do,” says Day. “I would practice in the mirror constantly.”

After inhabiting Cilla’s character all day during filming, Day found it difficult to switch back to herself in the evenings. “I even had anxiety dreams about having dinner with her!” she says. “Ultimately, I just want to do her justice. Nobody did what Cilla did. She went from girl next door to recording artist to TV superstar. She was a total girl boss.”

The art of impression and mimicry has a long and illustrious history going back thousands of years. Whether gentle homage, spiky satire or faithful on-screen biographical reproduction, we have always found fun, entertainment and fascination in the ability of one person to become another. It is a skill and a talent that even in this age of deep fake digital forgery and CGI trickery is a very human thing that can bring unexplained yet unalloyed joy, even if it’s just an “Ooh, Betty!”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks