The fear of nuclear annihilation raises its head once more

Like many children of the 1980s, David Barnett grew up with the fear of nuclear war. As global tensions over Ukraine intensify, he really doesn’t want to go back there

Ah, the spectre of nuclear annihilation once again raises its mushroom-shaped head, resurrecting the latent dread that is baked into the DNA of anyone who lived through the 1980s.

Not that the fear of nuclear war is the preserve of Generation X, Boomers and older cohorts; when atomic death starts raining from the skies, we’ll all be either immediately vaporised or reduced to scrabbling around the ruins of our cities hunting for rats to eat.

But for those of us who did live through the Cold War, the threats emanating from Russia do conjure up a particularly unpleasant set of memories of the time when nuclear war felt like a very real possibility — and sometimes, an inescapable probability.

As the 1980s began, I was ten years old. That same year, the Cold War really began in earnest as the Soviet Union began a programme of nuclear proliferation, siting nuclear warheads across its western borders and throughout the Warsaw Pact countries it controlled – Hungary, Poland, Albania, and countries that no longer exist in the form they did then, such as Czechoslovakia and East Germany.

We were a family that consumed news – on the TV at teatime and bedtime, throughout the day on Radio 1, and in print via the Daily Mirror and the local paper, the Wigan Evening Post. Even if I didn’t understand what was going on, I absorbed it through osmosis, until the certainty of nuclear war was entwined in my DNA.

It was a popular topic of conversation among my peers. I vividly remember sitting at a table at primary school, surrounded by friends. I drew a circle on a piece of paper and held a pencil upright in the middle of it. The pencil was a nuclear missile. The circle was the impact area, the centre of Wigan. We would all be dead if that bomb fell on us. I drew another circle around the first. We might be dead, I told my friends, if we live here. The buildings would probably come down. We’d get radiation sickness for sure, even if we survived the blast.

Another circle around those. Here, I said, we might survive. But for how long? We’d get sick, for sure. The animals would get sick. There’d be nothing to eat.

I got told off by the teacher for frightening the class.

Close to where I lived was a reclaimed, landscaped mining site, formed of grassed-over slag heaps with a popular fishing pond, the Trenchy. On a small hill overlooking a flooded quarry, across from a quiet, eerie railway line used by the nearby British Rail maintenance sheds for shunting rolling stock along for temporary storage, there sat a squat concrete box with horizontal slits in the side.

It had been a “pillbox”, one of many built close to the canal network during the Second World War, when there was a fear that if the Germans invaded they might use the waterways to push north. By the early 1980s it was the haunt of glue-sniffers, and a repository for empty cans of Kestrel lager and pages torn from porn magazines. It was also the place that my friends and I decided we would head for in the event of the four-minute warning.

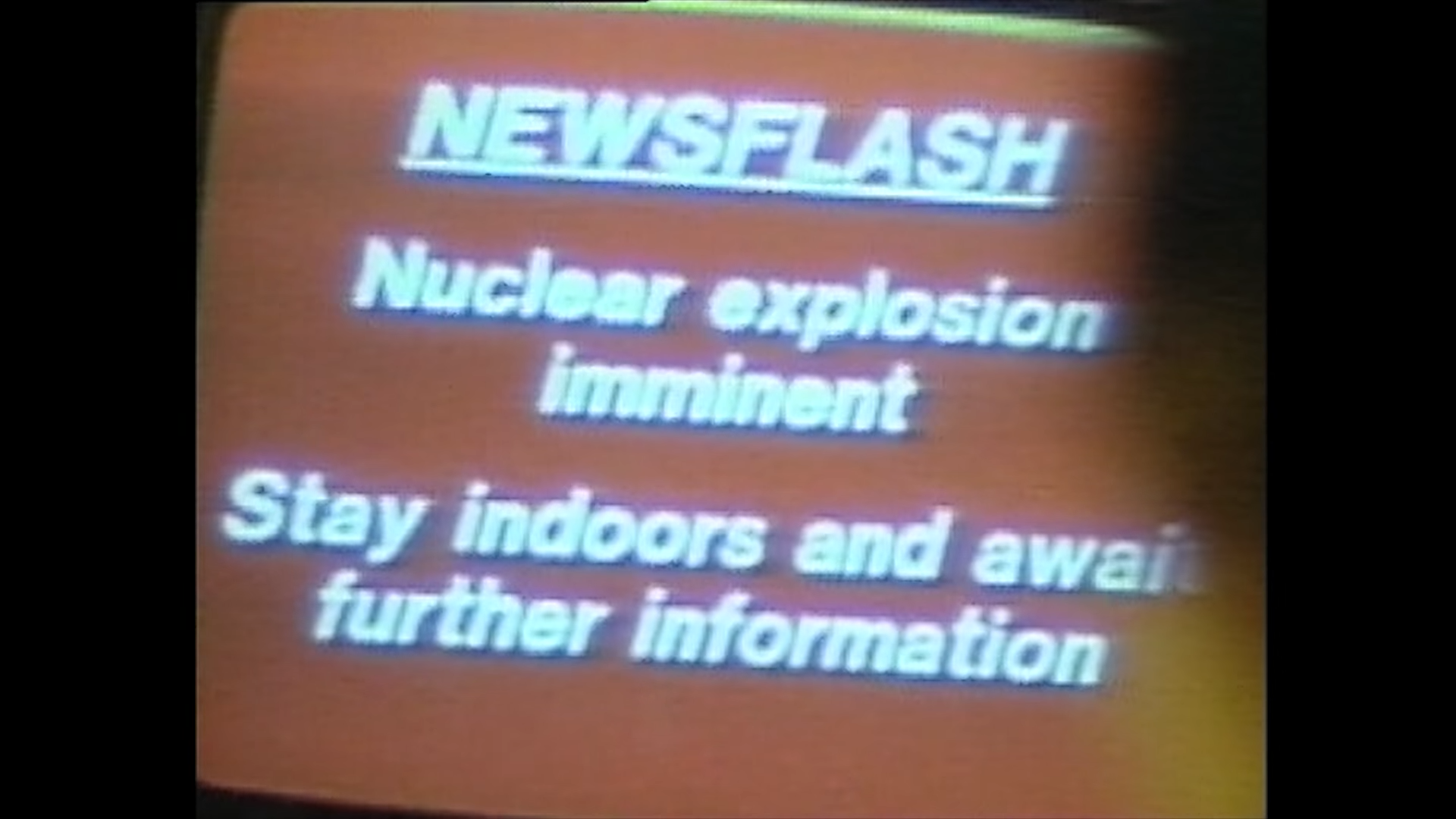

The four-minute warning was something I lay awake at night waiting for, the orange streetlights outside my window glowing diffusely behind the thin curtains while sweeping car headlights cast pale shapes on the dark ceiling through the ruched tops of the drapes. Why would we only be given four minutes’ notice of nuclear conflagration? What would I do in four minutes? Generally, in those pubescent years of the early 1980s, I decided I would run and tell whichever girl was the focus of my always unreciprocated desire that I loved her, and we would embrace as everything turned blinding white and the world ended.

We had no such organised contingencies. In fact, my mum once said that in the event of a nuclear war she would ‘get a gun and shoot us all’

I know exactly where that imagery came from. It was from the video for Ultravox’s 1984 hit Dancing with Tears in My Eyes. Because, although we were a news-consuming family, most of my atomic anxiety came from popular culture in the early 1980s, which was marbled and streaked with nuclear fear, like tributaries of white fat running through cheap bacon.

In Dancing with Tears in My Eyes, Ultravox frontman Midge Ure drives home as the nuclear reactor he works at goes into meltdown, to spend one last night with his lover before the world ends. Horrible, and romantic, and tapping into that baked-in fear we all had about this uncontrollable beast that was nuclear power, which we thought we could tame, like a wild, deadly stallion.

Music was full of nuclear war in the 1980s. And not all of it was as sombre and mournful as Ultravox’s entry into the canon. German singer Nena’s Europe-wide hit 99 Luftballons, released in English under the title 99 Red Balloons in 1984, is still a hit at wedding receptions, which gives me the chills. It posits a clutch of balloons floating into Soviet airspace and triggering a nuclear war, leaving Nena at the end “sitting pretty in this dust that was a city”.

Kate Bush’s typically bonkers Breathing from 1980 seemed to be about an unborn child worried about nuclear fallout from a war. Possibly. It was a little too obtuse to be frightening, and even songs that were more overt were often more hopeful than dour – see Captain Sensible’s Glad It’s All Over (1983), with its sinister submarines in the harbour but its paean to the “people who never, never go to war”.

But if the 1980s had an anti-war anthem with the strongest sense of partying at the end of everything and sticking two fingers up to the establishment that took us there, it has to have been Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s 1984 single Two Tribes.

With a pounding bassline and frenetic vocals, Two Tribes was a nailed-on hit, but it was the video that drove home the message – a no-holds-barred boxing match between fighters wearing masks of US president Ronald Reagan and Soviet Communist Party secretary Konstantin Chernenko, escalating into all-out war.

It was defiant and unruly, and, at 3 minutes 23 seconds, a viable alternative to the four-minute warning. If we had to die in heat, flash and wind, it might as well be to the soundtrack of this monster.

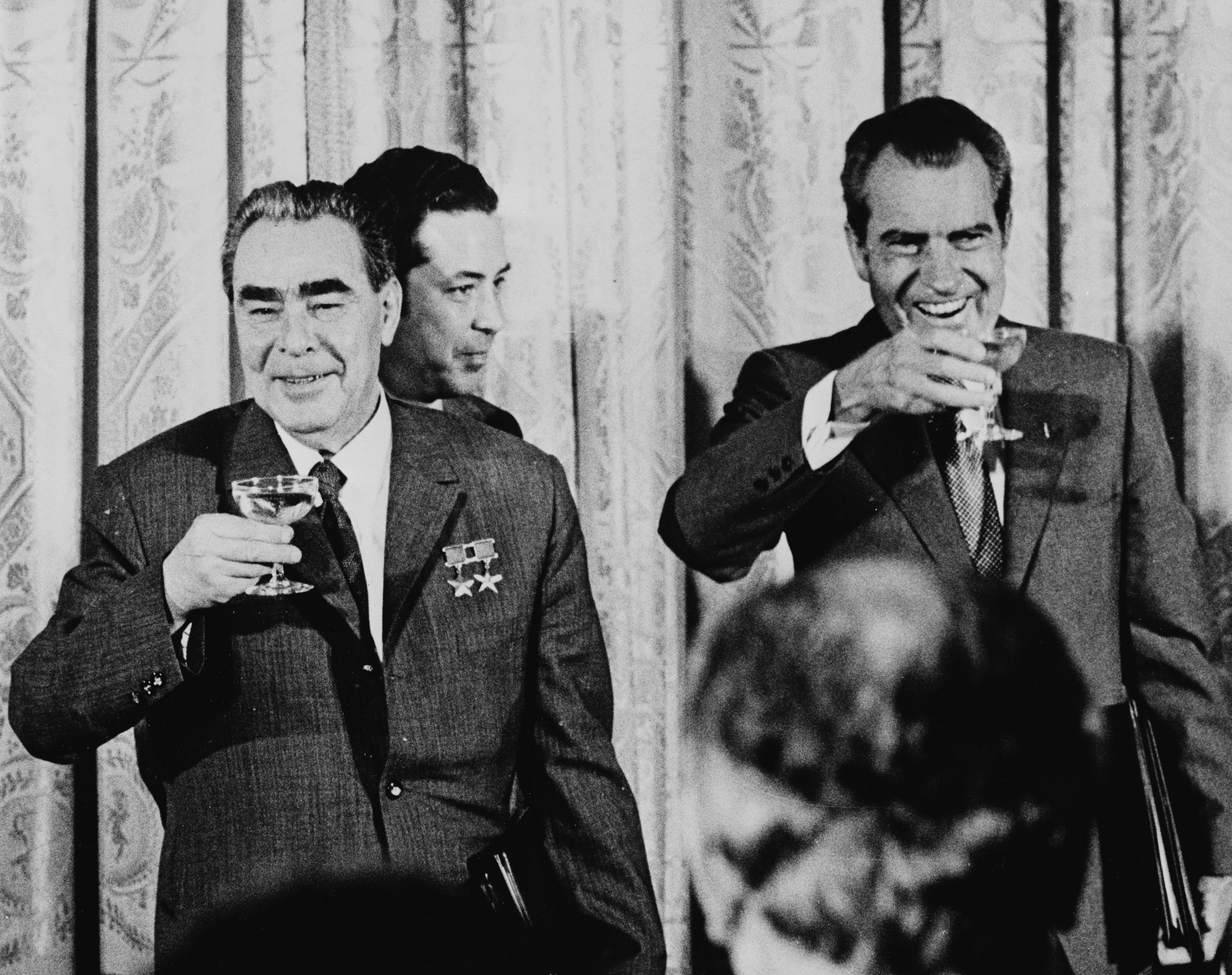

It felt in the early 1980s that the world was ruled by fanatical warmongers. Leonid Brezhnev in the Kremlin, Margaret Thatcher in Downing Street, former cowboy-film actor Reagan in the White House. It felt like they were sitting around a card table, stacking up nukes like poker chips and seeing who would fold first. Mutually assured destruction could only follow.

Two Tribes was grotesquely satirical and echoed the (recently revived) Spitting Image programme, which featured puppets of celebrities and politicians in scathing sketches. One of the most enduring running gags was about the president’s brain being missing – Reagan’s brain is removed for security reasons by his advisers, but takes on a life of its own and hops off. It tapped into the vein of global madness we were all being swept up in.

Nuclear gallows humour abounded on TV, exemplified by the 1982 sitcom Whoops Apocalypse, written by Andrew Marshall and David Renwick, who would go on in comparatively saner times to bring us, respectively, 2point4 Children and One Foot in the Grave.

Ghoulishly funny, the series charts the six weeks leading up to a devastating nuclear war, seen through the lens of comedic politicians and situations that were at once ridiculous and at the same time disturbingly credible. They even had the Soviets finding an ally in a British prime minister who secretly believed he was Superman. Perhaps the situations weren’t so ridiculous after all; prescient, even, with Marshall and Renwick only getting wrong the fact that their fictional PM was a Labour politician.

Hollywood bought into the apocalypse in a big way in the 1980s, too, of course. War Games was a 1983 thriller about the world being brought to the brink of armageddon when a teenage hacker unwittingly takes control of the US security computer systems, and thinks he’s playing a video game when he’s actually declaring war on Russia. It ends well, though, when the computer, locked into its programme, does what we couldn’t dare to believe our leaders would do, and declares that the only way to win the “game” is “not to play”.

Post-apocalyptic films had been on steady release since the 1960s at least, and the Eighties just ramped up the craziness. The second Mad Max movie, The Road Warrior, was released in 1981, as the Cold War was just getting going. And it suggested to us that, if we did survive the inevitable nuclear war, we would inexplicably have to start dressing in bondage gear and roaming the wasteland looking for water.

More sobering was the animated 1986 film of Raymond Briggs’s graphic novel Where The Wind Blows. No road warriors, no last-minute interventions. Just nuclear war, and the heartbreaking story of an elderly couple who survive it, trying to maintain a Blitz spirit in the face of this utterly planet-shattering calamity.

I asked a friend if it was just me who had been obsessed by the threat of nuclear war as a kid. No, she said. Her family lived close to an airbase near Warrington, and it was firmly believed that it would be a target once the nukes started flying. They had a nuclear attack drill, practising putting the mattresses against the windows to minimise the danger of flying glass as the howling, white-hot winds from the nuclear blast assailed their house. They worked out the quickest routes to get home when the four-minute warning sounded.

We stepped back from the edge of the abyss in the 1980s. And the threat of nuclear war receded, and we all hoped that’s where it would stay

We had no such organised contingencies. In fact, my mum once said that in the event of a nuclear war, she would “get a gun and shoot us all”. It was an ill-thought-out plan, to say the least. One, the only gun in the house was a pellet rifle that hadn’t worked for years. Two, my dad was a keen angler and, I think, had a fancy to head off to Scotland in the event of a nuclear attack and live off the bountiful produce of the clean, rushing Caledonian rivers and deep lochs, combining survival with his favourite hobby.

I remember my mum saying that so clearly because it came after perhaps the most infamous piece of popular culture informed by the impending terror of nuclear war.

Yes, it’s time we talked about Threads.

Threads was a British-made film that was broadcast at 9.30pm on BBC 2 on 23 September 1984. I have not watched it since that night, and yet every second of it is scalded onto my brain, like the shadows of the people of Hiroshima burned into the walls of the crumbling buildings of the Japanese city that suffered the first ever atomic bomb deployment in 1945. I will never watch Threads again: I don’t want to and I don’t need to. But I’m glad I did, even if it gave me nightmares for months.

Threads was made in a hybrid documentary/soap-opera style, and was written by Barry Hines, author of A Kestrel for a Knave and the screenwriter of the movie version of his classic book, Kes. The first half of the film introduces us to the principal characters, ordinary people in the South Yorkshire city of Sheffield, against a backdrop of rising tensions between Russia and the west.

Then, at 46 minutes, the bomb drops on Sheffield. It is one of the most harrowing and heart-stopping scenes ever committed to film. And the remainder of the movie is bleak, hopeless and soul-shrivelling as it documents the immediate aftermath of the attack, the breakdown of law and order, the degradation of infrastructure and control, and ultimately the utter collapse of society.

I remember there being a buzz at my secondary school the day it was on. The next morning, there was a sort of muted acknowledgement among us 14-year-olds that we’d all watched it, but only half-heartedly wanted to discuss it. This was no War Games; this was no Mad Max. This was pure, visceral, bile-rising horror. And it could happen. It really, really could happen. And it would happen just like this.

There’s a story that I’m not sure is true, but I want it to be. It’s said that Ronald Reagan was given a videotape of Threads, and after he’d watched it he started to pull back from the nuclear brinkmanship.

Whether it’s true or not, the second half of the 1980s started to see the world doing just that. And in 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became the leader of the Soviet Union, with a manifesto of reform and openness. The Afghanistan conflict that Russia had instigated in 1979, which had ushered in this final phase of the Cold War, was ended.

And the following year the unthinkable occurred, with the Chernobyl nuclear plant disaster. We saw first-hand what happened when nuclear power slithered out of our control. And what would happen if we rained bombs with many times the destructive capability of Chernobyl down on each other.

In 1968 the movie Planet of the Apes was released in cinemas. The central concept is that Charlton Heston’s displaced astronaut Taylor thinks he’s landed on a distant planet ruled by apes. But at the iconic ending of the movie, he realises the truth when he finds a half-buried Statue of Liberty on the shore. This is not an alien world. This is the future. After a devastating nuclear war.

Taylor falls to his knees, raging too late against his long-dead ancestors. “You maniacs! You blew it up! Damn you! God damn you all to hell!”

Except, we didn’t. We stepped back from the edge of the abyss in the 1980s. And the threat of nuclear war receded, and we all hoped that’s where it would stay.

Yet now it’s back. A week into the invasion of Ukraine, in the face of mounting international outrage, Russian president Vladimir Putin very publicly put his nuclear forces on “special alert”. And, most chilling of all, Russian state television host Dmitry Kiselyov declared in the wake of Putin’s announcement: “Why do we need a world if Russia is not in it?”

The spectre of nuclear war is back. We have people in control of nations who think that mutually assured destruction is a price worth paying. We have no reformer in the Kremlin, as we did in the 1980s; we have the opposite.

But still. We have been here before. And we have to believe, no matter how intense the international situation gets over Ukraine, that we don’t really have maniacs in charge who will blow us up, damning them and us to hell.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks