Elisabeth Frink: Sculptures dealing with timeless issues

With multiple exhibitions about Elisabeth Frink taking place, William Cook revisits her story and examines what drew him to her work in the first place

In a beautiful medieval tithe barn, in the heart of the Wiltshire countryside, gallerist Johnny Messum and his colleague Hannah Hooks are showing me around their new show, devoted to the late British sculptor Elisabeth Frink. The exhibition, titled Man is an Animal, opened in Bremen, Germany, last autumn and was due to travel on to the Netherlands, but that transfer was curtailed by Covid. When he heard about the cancellation, Johnny Messum acquired this sublime show for his gallery, Messums Wiltshire, just down the road from Frink’s old home and studio. The Netherlands’ loss has been Britain’s gain.

When I arrive, her sculptures have only just been installed, but it feels as if they’ve always been here; as if they were made for this ancient space. Frink’s heyday was the 1960s, 70s and 80s, but her work never seemed contemporary, even in her lifetime. It felt primeval, elemental – closer to antiquity than to modern art. I’ve seen Frink’s work all around the country and I’ve always loved it, but this 700-year-old building is the place where it feels most at home. “These figures could be from aeons ago,” says Messum. “You feel like you’re merging different levels of time here.”

“That’s why these works still resonate today, because they are essentially dealing with timeless issues,” concurs Hooks. “They’re dealing with human emotion.”

Elisabeth Frink was born in 1930 in Thurlow, Suffolk. Her father was in the army. During the Second World War she was evacuated to Exmouth, in Devon, where she saw aerial battles in the skies above and was once dive-bombed on the prom. “We saw all these enemy planes coming in over the sea, and we all fell to the ground,” she recalled. “They machine-gunned the parade we were on, and dropped bombs on the road above.” Frink wasn’t hurt, but 25 people died and 40 were injured. She suffered from recurring nightmares. It was in Exmouth that she started making art.

Her father, the absent soldier, loomed large in her war-torn childhood. “I was nine when the war started – I was very, very aware of aggression,” she remembered. “By the time I was 15, I knew about Belsen.” These formative experiences gave her a profound sympathy with all those involved in war – not only the victims, but those who are forced to do the fighting. Her muscular sculptures of naked warriors are menacing, but also strangely vulnerable. As she told the BBC, “The forms I make are inspired by a respect for life which seems to be always threatened by death.”

Success came early for Frink. She was still a student at what was then the Chelsea School of Art when the Tate and the Arts Council bought her sculptures. She’d only just left art school when she won an international competition to make a sculpture for the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts). From the late Fifties, her work was in constant demand. She was commissioned to make monuments for a huge range of public spaces, from sacred sites like Coventry Cathedral to new towns like Milton Keynes.

Why was her work so popular? Mainly because it was simply very good, but also because it bridged the gap between old and new, between figuration and abstraction. There was nothing old-fashioned about it, but it had a connection with the past which so much contemporary sculpture lacked. Her themes were archetypal, and her sculptures were accessible on many levels. They were full of meaning, but they were easy to understand.

In 1963 Frink separated from her first husband, the architect Michel Jammet (the father of her son, Lin Jammet) and in 1964 she married the war hero and businessman Edward Pool. In 1967 the couple moved to the south of France, and here Frink’s work became more smooth and polished, its rough surfaces burnished by the clear, sharp light. Immersed in the French countryside, she started to ride again – no wonder her sculptures of horses are so perceptive. No other modern artist had such an innate understanding of animals. She lived alongside them, and considered them her equals. “Animals have always been a very important part of my life,” she told the playwright Peter Shaffer. “Every being, whether it is animal or human, has a soul.”

Frink’s work was always one step apart from the mainstream. In our secular, irreligious age, it was defiantly, intensely spiritual

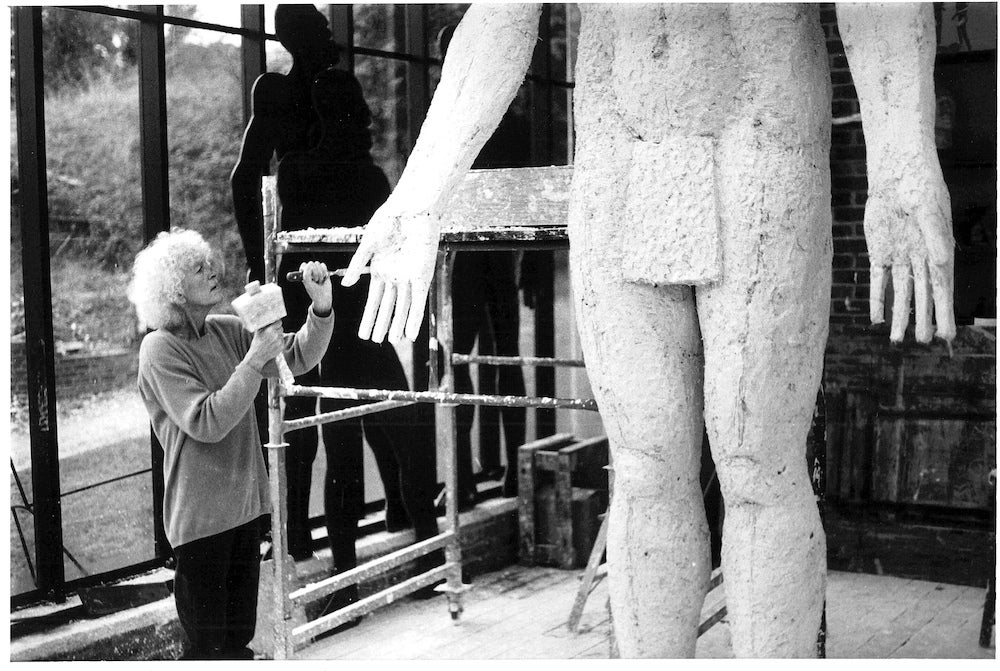

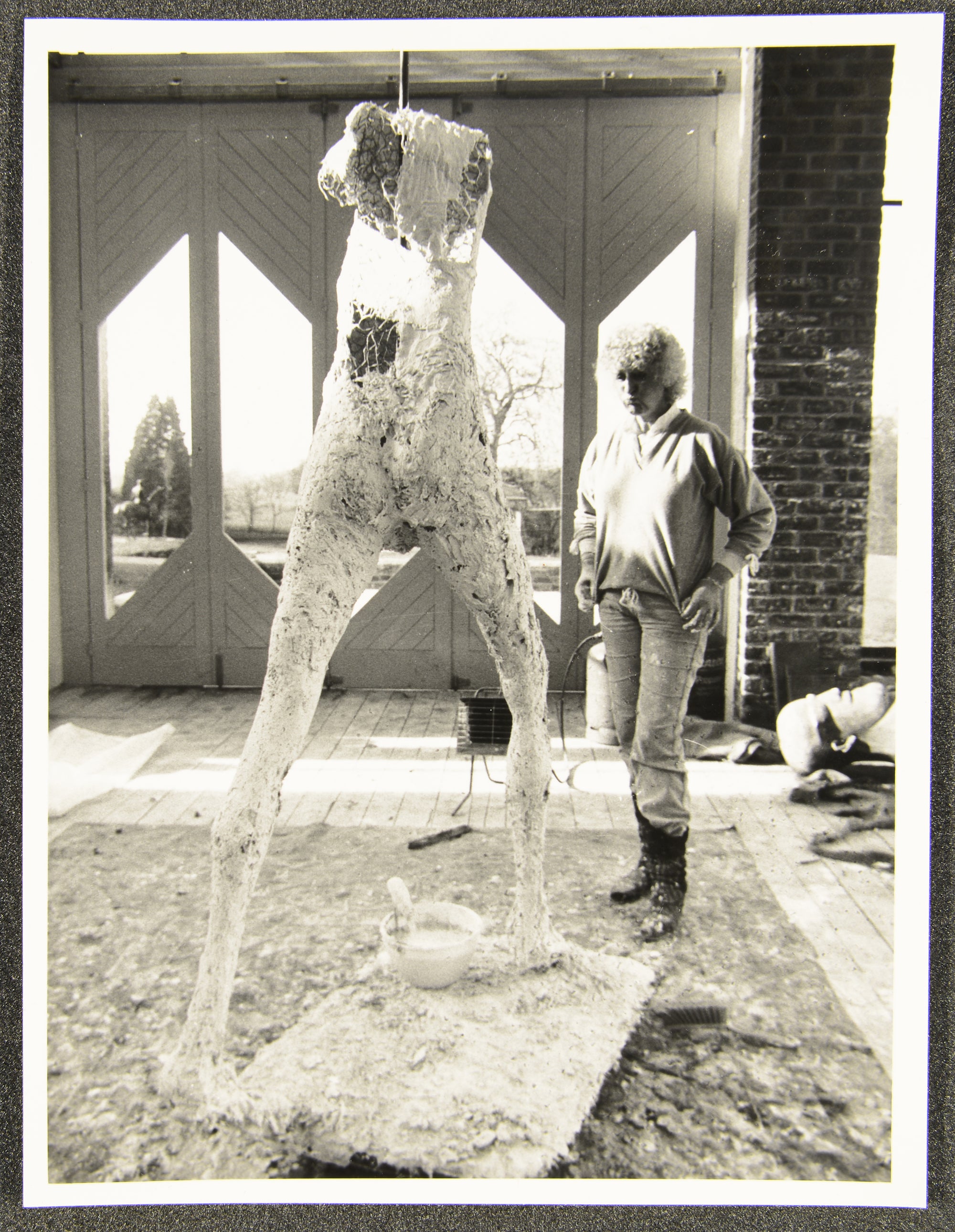

In 1973, Frink split up with Pool and returned to Britain. In 1974 she married for a third and final time, and with her husband Alex Csáky she moved to Woolland, in Dorset, where the couple built a spacious, sunlit studio. “Living in Dorset has opened up my vision enormously because for the first time in my life I’ve had a bigger space in which to put my sculptures,” she said. Personally and professionally fulfilled, her next 20 years were happy and productive. She was in the studio every day at 6.30am, but although her days were full of work, her evenings were convivial. “Her social and family lives were equally important, which was always something I admired about her,” said her son, Lin. In 1985 she had a solo show at the Royal Academy. A trip to Australia in 1986 gave her work a new lease of life.

The Nineties and Noughties should have been the summit of her career. Her hero, Rodin, did much of his best work in his sixties and seventies, and Frink looked set to do the same. However in 1991 she was diagnosed with cancer. “I’ve told it to go away,” she said, “because I want to see my grandson grow up.” But it came back. “It’s a disease everyone dreads, and it’s very difficult to come to terms with it because you feel very threatened,” she revealed, yet she carried on working, right up until the very end. Her final work was the gigantic Risen Christ for Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral (she’d made an altarpiece for the city’s Catholic cathedral 25 years before). She was very ill when she made it, but she was determined to finish it. She died just before its installation, in 1993, aged just 62. “I believe in the survival of the spirit, and of the soul,” she said, and her spirit lives on in her sculptures. The critic and curator Bryan Robertson called her “an artist of great courage, integrity and style”.

My preoccupation with Frink’s work began back in 1986, when one of her finest sculptures was erected on South Walks in Dorchester, a stone’s throw from my mother’s house. Today South Walks is a tranquil tree-lined avenue, flanked by handsome Victorian villas, but it has a long and bloody history. Frink’s statue stands on Gallows Hill, a scaffold for several centuries, where hundreds of people were executed, many for their religious beliefs. Two figures in Frink’s Dorset Martyrs stand side by side before an enigmatic robed figure – priest or executioner? It’s a masterpiece of understatement, all the more resonant for being sited in such a peaceful place with such a violent past. Walking past it, late at night, it inspired me like no other sculpture. I wanted to know more about the woman who made it. I wanted to see more of her work.

I didn’t have to look too far. From her Walking Madonna outside Salisbury Cathedral to her Ascent of Man in Manchester airport, her Horse and Rider in Piccadilly and her Blind Beggar in Bethnal Green, Frink’s monumental works adorn all sorts of public spaces. However in municipal museums, her work is conspicuous by its absence. Like that other great British sculptor, Barbara Hepworth, she was showered with honours in her lifetime; but her reputation hasn’t been preserved like Hepworth’s. She has no dedicated gallery. Her house isn’t on the tourist trail. In the 30 years since her death, her work has remained beloved by the general public, but she’s been largely ignored by the cognoscenti. She’s not part of the cultural conversation.

Why not? Fashion, mainly. Frink’s work was always one step apart from the mainstream. In our secular, irreligious age, it was defiantly, intensely spiritual – not tied to Christianity, but in touch with something deeper than the here and now. Unlike the unmade beds and pickled sharks of Young British Artists like Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin, her atavistic oeuvre didn’t suit our idea of Cool Britannia. It harked back to Greek gods and Norse mythology. It was rooted in the landscape, the rhythms and patterns of the natural world. It wasn’t knowing or ironic. It was emotive, passionate and sincere.

During those wilderness years, one woman toiled tirelessly to keep Frink’s name alive. The curator of the Frink estate, Annette Ratuszniak, compiled a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Frink’s works, and curated several important exhibitions. In 2015, she took me to a barn in Dorset where Frink’s work was stored, to meet Frink’s son, her only child, Lin Jammet.

Lin seemed like a kind and gentle man, proud and protective of his mother’s work, but a bit overwhelmed by the responsibility. And who could blame him? This barn was packed with sketches, maquettes and plaster casts – hundreds of precious artworks, many of which had never been on show. “Every day was a gift – she took full advantage of it,” he told me, shyly, as he showed me around. Enormous figures loomed over us, like Easter Island statues. It struck me that a lot of them looked a lot like Frink herself.

Lin looked a lot like his mother too, but his face had none of her fierce power – the square jaw, the steely gaze. Lis Frink was a striking woman – androgynous, amazonian. Compared to her, Lin seemed childlike, almost feminine. “She was so desperate to survive,” he told me. “She was so determined.” Lin was an artist, a good artist, but he never quite escaped his mother’s shadow. He died two years later, of cancer, like his mum. He was 59.

Last month I travelled to Dorchester to meet up with Annette Ratuszniak. It was the first time I’d seen her since Lin died. I hadn’t been back to Dorchester for 20 years. On my way into town I walked past Frink’s Dorset Martyrs, a memorial I’d walked past so many times, so long ago, and I realised it had become part of my own story, a landmark in my own life.

Lin’s dying wish was to distribute his mother’s works around the British Isles, and since he died, in 2017, Ratuszniak has been working to turn this idea into a reality. Thanks to her, and Lin, there are now Frink sculptures in public collections all over the UK, from the west country to Northern Ireland, but the Dorset Museum in Dorchester is the only place that has a permanent display of her work. Ratuszniak and I sat down there together. Surrounded by Frink’s sculptures, I asked her what made Frink unique.

“The way she works is so intimate,” said Ratuszniak. “It doesn’t matter what bit of the surface you look at on her sculpture. Her hand, her thoughts, her marks are there.” Unlike Hepworth, Frink didn’t use assistants. She made over 400 sculptures, and they were all made by her alone.

She was creating something which was very special and very different, and it had a presence

Like journalists, art historians like to tell clear and simple stories, and Frink doesn’t fit comfortably into the conventional history of 20th century British art. Her work shows that figuration is just as important as abstraction, that a lot of people prefer straightforward sculptures of men and animals to clever-clever minimalist or conceptual artworks, and that modernism was never the only show in town. “If you can’t pigeonhole someone in that sort of way it’s more challenging. You have to put a bit more work into it. You actually have to trust yourself, and your feelings, and I think the general public often do.”

The last Frink show Ratuszniak put on, at the Djanogly Gallery in Nottingham in 2015, was immensely popular. “People poured into that exhibition. They kept on coming back.” The stewards at the gallery told her they’d never known a show where people spent so much time with the artworks. “I think it’s because they’re very personal – you can tell your own story through them. You don’t have to be told what you’re meant to be looking at.”

Ratuszniak has a deep understanding of Frink’s work, but she didn’t know Frink well at all, so the next day I travel to Yorkshire to meet a man who knew her well, as a friend and colleague, for many years. Peter Murray founded the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) in 1977, and he was always a supporter of her work, so it was fitting that the YSP received one of the biggest bequests from the Frink estate – a vast array of her preliminary sketches and models. As he shows me round this treasure trove, I am reminded of my visit to Lin’s barn in Dorset. It is like being inside her studio; it is like being inside her head.

“She got a bit frustrated at times,” says Murray, over lunch in the YSP restaurant, overlooking the sculpture park he created, strewn with the work of Britain’s greatest modern sculptors: Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Anthony Caro and, of course, Elisabeth Frink. As Murray explains, sculptors like Caro (who was an influential tutor at St Martin’s School of Art, as well as a famous sculptor in his own right) took British sculpture off in a different direction – more abstract, less figurative – and so Frink became sidelined.

“When Tony Caro and people from St Martin’s started to reassess what sculpture was all about, she was, to a very large extent I think, left behind.” Yet what goes around comes around. The art world has changed, figurative art is back in vogue, and Frink’s work is now more in tune with the times than it was at the end of her own lifetime. “I think Lis is part of that change in attitude towards what sculpture is, what sculpture should be.”

To his credit, Murray was never swayed by these artistic fads and fashions. “I thought her work was relevant. I thought it had a quality. I thought it had an individuality.” And as they got to know each other, he was intrigued to see her style develop. “As she got older, what was beneath the surface of the sculptures became more and more important,” he tells me. “The emotional intensity is inside the work.”

Frink invited Murray to visit her at her home in Woolland, Dorset. “I found her very approachable. She was always incredibly friendly.” They became firm friends, and he returned to Woolland many times thereafter. “She was great fun – we had some riotous evenings,” he recalls. “She was a great cook – she used to like to cook. There was always plenty of champagne around. She really enjoyed entertaining.” But although she loved to let her hair down, her art came first. “No matter how late she’d been up the night before, she’d be in the studio first thing in the morning.” Frink started visiting Murray at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and in 1983 he mounted an exhibition of her work here. When she died, ten years later, he staged a memorial exhibition. “She was creating something which was very special and very different, and it had a presence,” he says. You can still feel that presence in her works on show here.

Her death was a shock for him. “I was extremely upset. I knew she was ill, but I didn’t know she was that ill.” Frink always wanted a significant number of her works to be sited at the YSP, and after she died, Lin was keen to make it happen. “He certainly wasn’t interested in selling. He wasn’t interested in making a quick buck, or anything like that. He was really truly interested in preserving the legacy of his mum.”

After Lin died, Ratuszniak duly arranged for a selection of Frink’s sculptures to come here. Her sculptures feel at home in the Dorset Museum, among the Roman mosaics and Neolithic relics. They feel at home in the Yorkshire landscape, part of the rugged scenery that surrounds them. Maybe it’s no bad thing that there aren’t so many of her sculptures in big galleries. She preferred to see them outside, in the open air. She made them in the countryside, and they should be seen here in the countryside. They seem lost and lonely in the city.

Back at Messums, they’re unwrapping the last few sculptures. Seeing them in here, all together, I’m struck by how brave and honest they are. “It takes a certain confidence to leave your emotions on the table,” says Johnny Messum, as we stand and watch them. I know exactly what he means. Great sculpture is intensely physical, like great acting; closer to performance art than fine art. It takes a lot of guts to bare your soul like this – it’s easy for folk to take the piss. For a long time, the smart set thought Frink was uncool, but now her time has come again. We’ve grown tired of art that’s suave and cynical. We want some raw emotion. We want the real thing.

“She was clearly a very, very strong woman,” says Hannah Hooks. “She stuck to what she wanted to do.” That’s it, in a nutshell. There’s nothing more to say. As I walk back to the station, I pass some young cattle in a field and I stop and watch them for a while – a little while longer than I would have done before. I end up wondering what Frink would have made of them, how she would have sculpted them. That’s what makes her so special, what makes me love her sculptures. After you’ve spent some time with them, you start to see the world around you in a slightly different way.

Elisabeth Frink: Man is an Animal is at Messums Wiltshire until 16 January 2022 (www.messumswiltshire.com). You can see more of Frink’s work at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (www.ysp.org.uk) and at the Dorset Museum in Dorchester (www.dorsetmuseum.org)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments