The lure of the Matterhorn and why so many risk their lives to climb it

To mark the 150th anniversary of the first woman to climb the Matterhorn, Olivia Jane is preparing to make the 4,478m ascent of this unforgiving and exposed peak. William Cook catches up with her in Zermatt

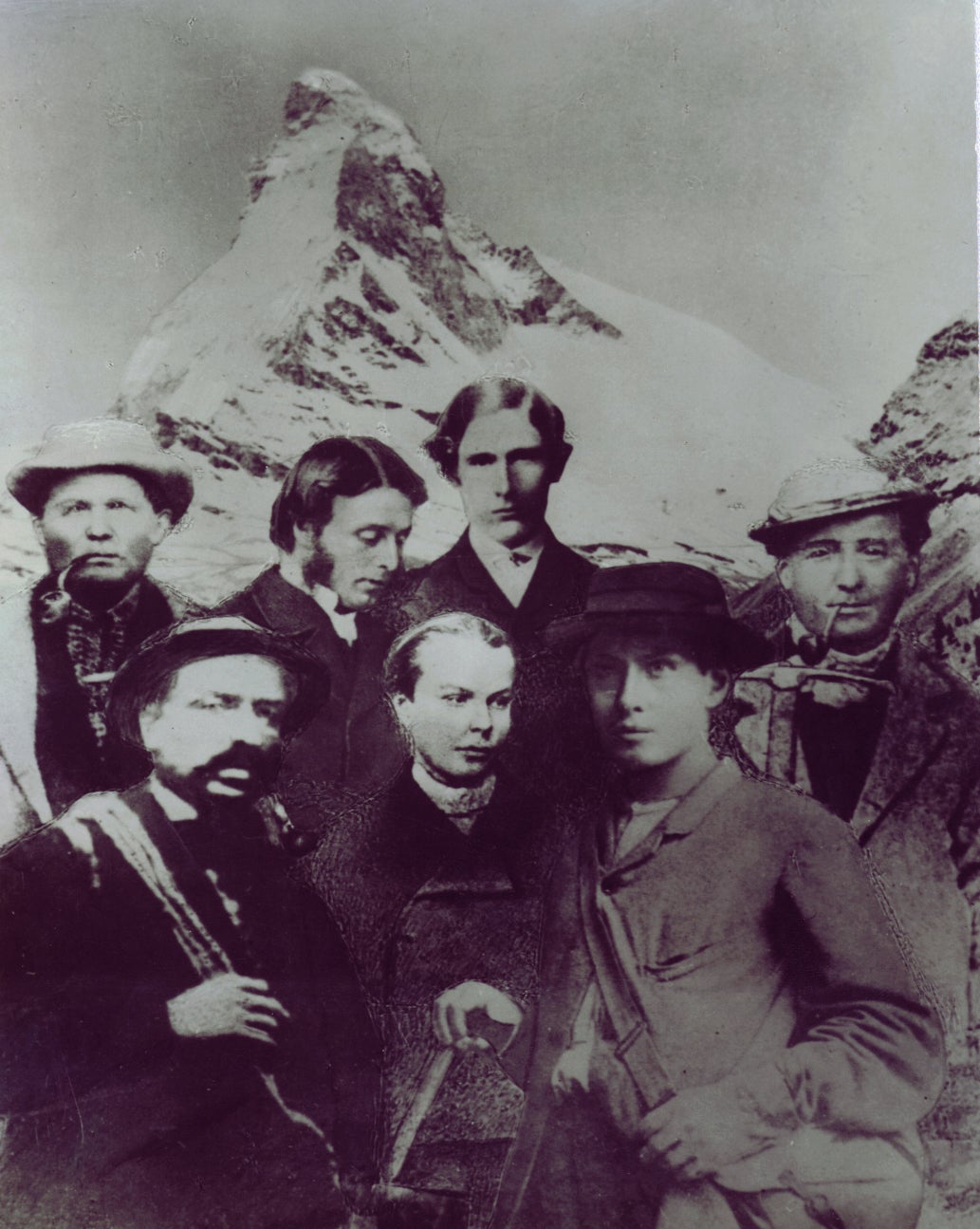

In a quiet corner of the Monte Rosa Hotel in Zermatt, Switzerland’s highest ski resort, there is a room full of faded photographs of Britain’s bravest (and most reckless) mountaineers. These are the pioneers of mountaineering – those heroic, foolhardy Victorians who scaled the most perilous peaks in Switzerland with the most rudimentary equipment, dressed in the sort of tweedy garb you might wear for a Sunday afternoon stroll.

These photos all look much the same, but one face stands out amid the crowd. Among this sea of men is one woman, Lucy Walker, the first woman to scale the Matterhorn in 1871. To mark the 150th anniversary of her climb, a young British mountaineer called Olivia Jane has come to Zermatt to follow in her footsteps up the Matterhorn, and I’ve come here to meet her. I want to find out why this mountain has always been such an object of fascination. I want to find out more about Lucy Walker. And I want to know what drives Jane to do something most of us would never dare to do.

Approaching Zermatt by train, on a single track that clings to steep hillsides and straddles vertiginous ravines, you begin to realise what an ordeal it was for Alpinists such as Lucy Walker to even get here, let alone climb the Matterhorn when they arrived. The train only takes an hour from Visp, at the mouth of the valley (ascending 1,000 metres en route), but this line wasn’t built until 1891. When Lucy came here, 20 years earlier, the only way to reach Zermatt was on foot, along the old mule trail that runs up the valley.

When you finally reach Zermatt, and see the Matterhorn for the first time, you realise why it’s enthralled so many mountaineers – and why so many of them have risked (and often sacrificed) their lives to climb it. I’m no climber (I get giddy up a stepladder) but I love to hike, and I’ve been all around the Alps. I thought I’d seen it all before, but the Matterhorn takes your breath away. It’s like no other mountain I’ve ever seen before. It’s like no other mountain in the world.

What makes it so special? Its incredible shape, for one thing. Most mountains in the Alps have been tempered by the elements. Their sharper edges have been smoothed away. On a sunny day, from a safe distance, they almost look accessible. The Matterhorn looks completely different. It rises to a sharp point, like a mountain in a fairytale. Its sides look almost sheer.

The other thing that makes the Matterhorn so special is its splendid isolation. Most mountains come in clusters. Even Mont Blanc, the highest mountain in the Alps, is surrounded by slightly smaller peaks. By some strange freak of geology, the Matterhorn stands alone, a single snowcapped peak. No artist can do it justice. In paintings it looks implausible, unreal.

Gazing up at the Matterhorn it looks like an impossible feat to climb it, and for a long time it seemed that might well be the case. During the so-called Golden Age of Alpinism, from 1854 to 1865 (the decade when climbing in the Alps took off), other Alpine peaks fell like ninepins, but the Matterhorn remained unconquered. Numerous climbers attempted it, but they were all forced back, mainly by bad weather (the Matterhorn’s isolated position leaves it uniquely exposed to the elements).

Eventually, in 1865, British climber Edward Whymper led a team of seven up to the summit, narrowly beating an Italian team, which was ascending from the other side. However, triumph turned to tragedy as the British team made its way back down. One member of the team, a 19 year-old novice climber called Douglas Hadow, lost his footing and fell. His teammates were roped together but the rope snapped, and three others (Lord Francis Douglas, the Reverend Charles Hudson and a Swiss mountain guide called Michel Croz) were dragged down with him to their deaths.

The catastrophe made front-page news back in Britain. There were calls for mountaineering to be banned (even Queen Victoria voiced her concerns) but no publicity is bad publicity, and the controversy did Zermatt no harm at all. For British mountaineers, the Matterhorn remained the ultimate challenge, and the Monte Rosa became a busy rendezvous for legions of British climbers, drawn to the Matterhorn like moths to a flame.

Mountaineering wasn’t merely regarded as unladylike. Victorian women were routinely dismissed by Victorian men as fragile, hysterical creatures, physically and mentally ill-equipped for all but the most genteel pursuits

It was five years after this disaster that Lucy Walker climbed the Matterhorn. She wasn’t the first woman to try. In 1869, a woman called Meta Brevoort got within 500m of the summit before bad weather forced her back. In 1871, Meta set off for Zermatt, determined to give it another go. Lucy was already in Zermatt, with her father and her brother. When they heard Meta was on her way, they assembled a team and made it to the summit ahead of her. When they returned to Zermatt, Meta was there to greet them.

Sportingly, Meta swallowed her disappointment and congratulated Lucy on her achievement. It was the only time the two women met. Meta went on to climb the Matterhorn, and numerous other Alpine peaks. She died in 1876, of heart disease, aged just 51. Lucy hung up her climbing boots in 1879, but she lived until the age of 80, dying of natural causes in 1916.

What Lucy and Meta achieved would have been remarkable in any era, but in the 1870s it was exceptional, for this was an age when women were actively discouraged from doing virtually any exercise at all. Mountaineering wasn’t merely regarded as unladylike. It was considered to be the sort of thing that women were utterly incapable of doing. Victorian women were routinely dismissed by Victorian men as fragile, hysterical creatures, physically and mentally ill-equipped for all but the most genteel pursuits.

It's surely no coincidence that both Lucy Walker and Meta Brevoort were born and raised in America (Meta was from New York, Lucy came from Canada). Attitudes towards women’s roles were less restrictive in the New World, and although both women ended up in England, they brought these New World attitudes with them. Class was another factor. Then as now, you needed time and money for mountaineering, which confined it to the upper- and middle-classes, but these were the classes where women’s roles were most curtailed. Meta and Lucy came from rich families, but their families were merchants, not gentry. By snobby Victorian standards, they were arrivistes.

One hundred and fifty years later, Lucy’s historic climb is widely acknowledged here in Zermatt, but it’s still a lot less prominent than Edward Whymper’s ascent, five years before. Of course, being first always gets you more plaudits – just ask Meta Brevoort – but to my mind what Lucy (and Meta) did was far more monumental. Whymper scaled the Matterhorn alongside half a dozen other men a few hours before an Italian team and lost four men on the way down. Lucy (and then Meta) matched his achievement just a few years later, overcoming the sort of prejudice that no man could imagine.

Which brings us to 2021, and Jane’s impending climb. I meet her in the lobby of her three-star hotel, an unassuming modern building, a lot more modest than the Monte Rosa. Over coffee in the hotel bar I ask her what brought her to a mountain which has claimed the lives of more than 500 people since Lucy Walker’s day. She doesn’t make a living out of climbing (she has a day job, working for a company that organises trail-running festivals around the British Isles) but it’s quite clear from talking to her that climbing is her vocation. “It’s just passion,” she tells me. “That’s all it is.”

Jane is 29 but she looks both older and younger. She’s lithe and slim, with the body of a teenage gymnast, but her voice has adult gravitas and there’s adult wisdom in her eyes. She’s here with her partner, Tom Lemar, a young man with a boyish friendly face and the body of a superman. They often climb together. “That’s why I dragged him along with me – because I want him to come up with me.” He might climb the Matterhorn with her, if the weather holds.

In midsummer there should be hardly any snow on the mountain, but right now it’s caked in it ... usually, this time of year, it’d just be snow on the peak – but it’s all the way down

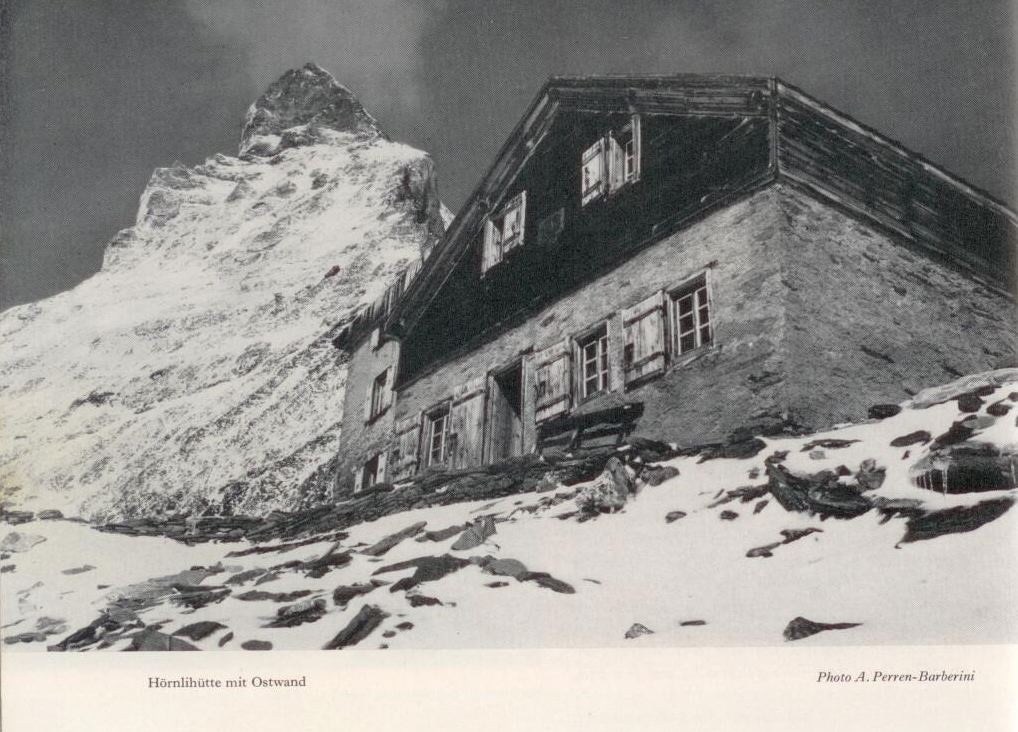

The weather is a problem, as it so often is on the Matterhorn. In midsummer there should be hardly any snow on the mountain, but right now it’s caked in it (“usually, this time of year, it’d just be snow on the peak – but it’s all the way down”). She’s due to climb the Matterhorn in five days’ time. If there’s still too much snow when the big day dawns she won’t go up. It’d be too dangerous. Thankfully, it won’t be her decision. Her guide will decide. Like Walker before her, she’ll be climbing with a local guide. It’s an essential safety requirement. “You can never really do anything like this on your own,” she tells me. “You always need to be with somebody.”

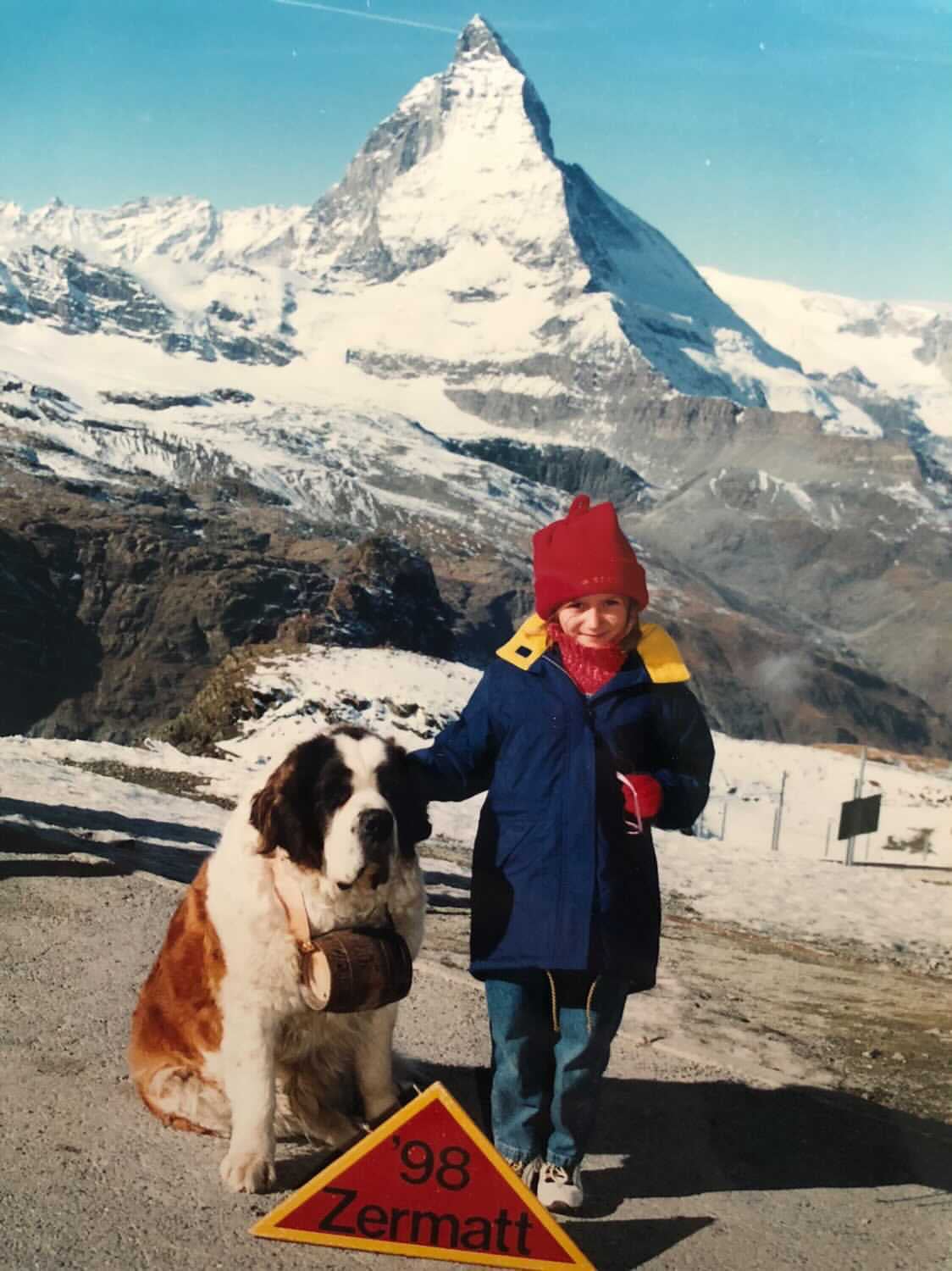

Jane started coming to Zermatt when she was a child. “I came out here pretty much every summer.” Her aunt had a business here. She was a photographer, and she bred St Bernards. Tourists used to pose for photos with them. Jane loved her summer holidays here, but she used to hear about the fatalities on TV – yet another climber had gone up the Matterhorn and hadn’t come back down.

She didn’t remember hearing about the climbers who made it safely back again. That didn’t seem to make the headlines. “It was always in the news that somebody had died – it didn’t put me off though,” she says, with a quiet chuckle. “I do remember saying to my grandparents that I’m going to climb it one day.” And now that day has come. When Jane was 10 her grandmother bought her a necklace with a silver pendant of the Matterhorn, but she didn’t give it to her. Instead, she kept it in a drawer for nearly 20 years, until Jane told her she was coming here to climb the Matterhorn. “She gave it to me just before I came here.”

Jane was born in Manchester and grew up in Lancashire. Nowadays she lives near Chorley. She spent a lot of time in the mountains as a child (“I’ve always been passionate about the mountains”). Her granddad took her hiking and scrambling in the Lake District, but she only started mountaineering six years ago, when she was a student at Salford University. The extraordinary thing about her story is that it was the Matterhorn which came first. “I knew I always wanted to climb it, so it got to a point in my life where I thought, ‘I need to start learning how to do it’.” She joined the student mountaineering club and went to Scotland with some seasoned climbers who showed her the ropes. She didn’t encounter any gender prejudice. The men were all really encouraging. “I love this,” she thought.

But what about the fear factor, I ask, mindful of my dreadful head for heights. “There was no fear,” she says. From then on, there was no stopping her. “I started going on courses, I wanted to learn more things, and then I started ice climbing, and then I started going to different countries. It just kept growing and growing and growing.” She’s climbed in France and Italy and here in Switzerland. She climbed a 6,000m peak in Nepal.

It was the outdoor sports clothing company Mammut, which invited her to do this trip. She was planning to come out here with Tommy anyway, and she got on to Mammut to ask for some free kit (“I was just cheeky – if you don’t ask, you don’t get”) and then they told her about this project, which Mammut was working on with the Swiss tourist board, to mark the 150th anniversary of Walker’s climb. She sent them a picture of her as a kid, stood in front of the Matterhorn. She reckons that’s what clinched it.

Apparently, the Matterhorn isn’t the hardest peak to climb – not technically, at any rate. It’s more of an endurance test – anything from eight to 16 hours, depending on the weather. People always focus on the ascent, but the descent is even harder. “That’s always the case,” says Jane. “Everyone gets to the top and they’re like, ‘Oh my god, I’ve done it!’ But the most dangerous part is coming down.”

“The ascent’s not too bad, because you’ve got a lot of fixed lines,” says Tommy. It’s on the way back down that you can take a wrong turn and end up somewhere you didn’t mean to go.

Another peril is falling rocks. “You can’t do anything. If you get hit by a rock, you get hit by a rock. There’s nothing you can do.” The Matterhorn can be psychologically taxing too. Jane tells me about a friend of hers, who’s a professional climber. “He attempted it, and he said he felt scared. It wasn’t so much the climbing – it was the exposure. You can step out on to a ledge and it’s just a sheer drop.” It makes me shudder to even think of it, but not Jane. “Everybody’s different. Some people don’t have that fear.”

So why does she do it? “I know it sounds weird, but I like things that are dangerous,” she says. “I’m addicted to that adrenalin.” She has three younger half-brothers but no full siblings, and I can see something in her of the classic only child: that obsessive single-mindedness; that attractive, awkward mix of introvert and extrovert. “It makes me happy being in these environments and putting myself out of my comfort zone.”

I’m always cautious. I definitely respect it, probably more so now than I ever did, because I know the dangers and I know what can happen, so I don’t get over-confident. If anything, I take extra care

I keep feeling there’s something she isn’t telling me, and finally she comes out with it. “I’m a mum. I’ve got an eight-year-old girl. I feel like I can’t be selfish, because if something did happen to me…” Her voice tails away. So how much does her daughter Annie know about all this, I ask her. “A lot,” she says. “I’ve taken her climbing a few times. She’s always in the mountains with me.” It sounds as if Annie loves it. “My daughter doesn’t know what fear is.” She sounds a lot like her mum.

So how would Jane feel if Annie ever decided to start climbing seriously? “I’d love it. I’d support her. You can’t stop your children. If they want to do something, you’ve just got to support them, haven’t you? I don’t want to say to her, ‘No, don’t do it because it’s dangerous’.” As she says, it never stopped her from doing dangerous things when she was a kid.

Jane may be fearless, but that doesn’t make her reckless. “I’m not cocky,” she says. “I’m always cautious. I definitely respect it, probably more so now than I ever did, because I know the dangers and I know what can happen, so I don’t get over-confident. If anything, I take extra care.” In mountaineering, more than anything, you have to know your limits. Some young climbers end up dying, she tells me, because they go beyond their natural boundaries. “If I didn’t have a kid, I’d probably be one of those people.”

I tell Jane about my visit to the Anglican Church in Zermatt, and my conversation with the visiting chaplain, a kindly woman called Liz Leaver. I asked the Reverend Leaver about all the plaques around the church, and the gravestones in the graveyard, commemorating the many young men who’ve died on the Matterhorn and the other mountains that surround it.

The gist of what Liz said was that none of us know how long we’ve got, and that young people are driven to take risks. If these young men hadn’t risked (and lost) their lives on the Matterhorn they might have risked them doing something else. “I never thought of it like that,” says Jane, but it sounds like she agrees. “If I’m going to be doing something dangerous, I’d rather be doing something like this.” Something magnificent and magical, like climbing up a mountain. “It’s special in the mornings when no one else is awake,” she says. “Everyone else is asleep and you’re there, stood at the top.”

Despite her love of mountaineering, she has no desire to do it full time. “It’ll always be for passion. I don’t want to be professional, because then I feel the dynamic of it might change and I won’t love it as much.” She just wants to carry on climbing 4,000m summits (“until I can’t walk anymore”). And what about her daughter, Annie? “I’d love to do one with Annie one day.” Last night, here in the hotel, quite by chance, she met a father and son, aged 18, who’d climbed the Matterhorn that day. “I’d love to do that with her.” When Annie is 18, she’ll be 39. Maybe they’ll climb the Matterhorn together? That’s a story I’d love to cover, if I’m still around.

Next morning, I return to the Anglican Church for the Sunday morning service. The Reverend Charles Hudson, who made that first ascent of the Matterhorn, in 1865, and died on the way down, is buried beneath the altar. The readings are from the bible he took to the Crimea. Douglas Hadow, who died with him, is buried in Zermatt’s main graveyard. Lord Francis Douglas is still on the mountain. His body was never found.

“We remember those who have lost their lives on these mountains,” says the vicar. As my train trundles back down the valley, I take a last look at the Matterhorn. Yesterday it was obscured by cloud but today the sun is shining, and its snowcapped peak is so clear and bright you feel you could reach out and touch it. And then we turn a corner, and the mountain disappears.

For more information about Alpine mountaineering trips for women, visit https://www.myswitzerland.com/en-gb/

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks