How Zurich became the centre of Europe’s avant-garde

The story of literary heroes who turned Zurich into a beacon of intellectual liberty during the Third Reich can tell us a lot about our own age of intolerance and resistance, writes William Cook

In a beautiful old bookshop in Zurich, a short walk from the lake, Doctor Michaela Unterdörfer is telling me about the Swiss couple who made this shop a beacon of intellectual liberty during the dark days of the Third Reich. It’s not a story of spectacular heroism but discreet and dogged resistance, and that’s what makes it such a potent tale for our troubled times.

Switzerland in 1933 was very different from Britain in 2020, but there was one striking similarity: across the border, 20 miles away, were countless refugees seeking sanctuary, yet the authorities said, “the lifeboat is full”.

Those authorities were Swiss and those refugees were German Jews, but the comparisons with Britain today are telling. Then, as now, these refugees were regarded as someone else’s problem. Then as now, the government reckoned they had enough headaches of their own. Only a few folk cared enough to reach out to persecuted people beyond their own borders, and two of the folk who cared were the young Swiss couple who ran this bookshop.

Emil and Emmie Oprecht opened their bookshop here on Rämistrasse in 1925. Emil had just turned 30. Emmie was 26. Their shop flourished and, when Hitler came to power, they responded by founding a publishing house called Europa Verlag. This name reflected their internationalism. Specialising in political books, especially by exiled authors, it became an important forum for German writers (such as the novelist Thomas Mann and the philosopher Ernst Bloch) who’d been silenced in their native land. More than a hundred German and Austrian authors were published by this enterprising couple (they also published the Italian anti-fascist writer Ignazio Silone).

With Europe in a state of panic, as nation after nation turned to fascism, there was a ravenous appetite for Europa Verlag’s challenging, progressive output. A collection of anti-Nazi essays called Gespräche mit Hitler (Conversations with Hitler) sold over 30,000 copies. Naturally, the Nazis weren’t best pleased, but Emil and Emmie were indifferent to intimidation. When their books were banned in Germany, they responded with a daring window display of censored titles, piled high like a funeral pyre.

Officially, Switzerland was neutral – an island of democracy and liberty, not at all beholden to the Third Reich. Unofficially, the situation was more complex. German was the mothertongue of most Swiss citizens. The two countries enjoyed close cultural and economic ties. Here in Zurich, life was especially fraught. This was a German-speaking city with many German residents, not all of whom were anti-Nazi. The Swiss army was no match for Hitler’s Wehrmacht. The German border was barely 20 miles away.

The Swiss authorities were loath to antagonise their German neighbours, and so Emil and Emmie received scant support (and a good deal of obstruction) from their fellow countrymen. In 1937, when Emil was expelled from the Association of German Publishers and Booksellers, the Swiss Federal Council followed suit by threatening to ban their books. Their activities were monitored by the police and, after 1939, by the army too.

Throughout the Second World War, Switzerland’s future remained uncertain. As the war dragged on the country remained unoccupied, but no one knew how long that would last. Hitler’s Germany lay to the north and Mussolini’s Italy to the south. After the Anchluss and the fall of France, Switzerland was surrounded. The Swiss Patriotic Federation, which was sympathetic to Nazi Germany, had many influential supporters, especially in the upper echelons of the Swiss army. Whether you were for collusion or resistance, a German invasion looked highly likely. If you were anti-Nazi, the Oprechts’ work was a source of peril. If you were pro-Nazi, it was an affront.

The Oprechts’ apartment, on Hirschgraben, was opposite the German consulate. “It was a huge risk for them,” says Unterdörfer. Yet Emil and Emmie weren’t deterred. Now the foreign authors that they championed were in even greater danger, they stepped up their efforts. They didn’t just give these authors a platform for their work. They put them up and found new homes for them. If they’d entered Switzerland illegally, they hid them from the Swiss police. “All available means were mustered to help the persecuted,” said Emmie. “Every life counted.” For those dissident writers who made it into Switzerland, their bookshop was a lifeline – a source of information and companionship, a place to make contacts and exchange ideas.

If anything, the Allies appreciated their efforts more than the neutral Swiss. News of their work reached all the way to Downing Street, and the White House. “I have been told of the great difficulties which you have to encounter,” wrote Winston Churchill in a personal letter to Emil, “and I would like to say how much I and the authorities concerned here value the work which you are doing.” President Roosevelt also conveyed his heartfelt thanks. “We can understand to what lengths our friends have gone in their fight to liberate the world from Nazi oppression,” wrote FDR. “We cannot know of all the risks and dangers which such friends of the Allied cause endure.”

Yet it was only once the war was over that Swiss attitudes shifted. “That’s odd – we’re suddenly in demand,” observed Emil, sardonically, when he was invited to the Bundeshaus, the Swiss seat of government in Bern, in 1945. “After having been suspected and outcast for years, harassed in every conceivable way and tormented with censorship, we are politely received and asked for our advice.” It was a different story during the war.

Sadly, Emil only had a few years in which to enjoy this belated recognition. In 1952 he died of cancer, aged just 57. “My most beautiful memory of him is of an hour in his office on New Year’s Eve, 1936, when I read out loud to him a letter I had just written, a polemic against the corrupters of Germany, which – thanks to his initiative – became world news,” remembered Thomas Mann. After he'd finished reading him this letter, Emil took his hand and held it. Emil didn’t say a word, but his eyes were full of tears.

Emmie carried on the business after her husband’s death, but its glory days were over. She died in 1990, at the grand old age of 91. The bookshop shuffled on until 2003, when it became a travel agency. I must have walked past it a dozen times without ever knowing what had gone on in there. But then last year Hauser and Wirth, one of Switzerland’s leading commercial galleries, bought it and turned it back into a bookshop, under Michaela Unterdörfer’s stewardship. Michaela and her colleagues have done a super job. It’s a lot less cluttered than it used to be, but the old ambience is still there. Here’s hoping it’ll become a forum for a new generation of independent thinkers, folk who refuse to keep their heads down, who aren’t afraid to go against the grain. “What we want is to create a space for free speech,” she says.

The Oprechts’ valiant work didn’t happen in isolation. They were part of a counter-culture which has thrived in Zurich for a century. Despite its smooth veneer of affluence, and its conservative reputation, this sedate city has long been a magnet for refuseniks, a centre for Europe’s avant-garde. Immigration has enlivened and emboldened the cultural life of this city. “There’s a huge energy brought in by individuals from all over,” says Unterdörfer. And that’s as true today as it was in Emil and Emmie Oprecht’s day.

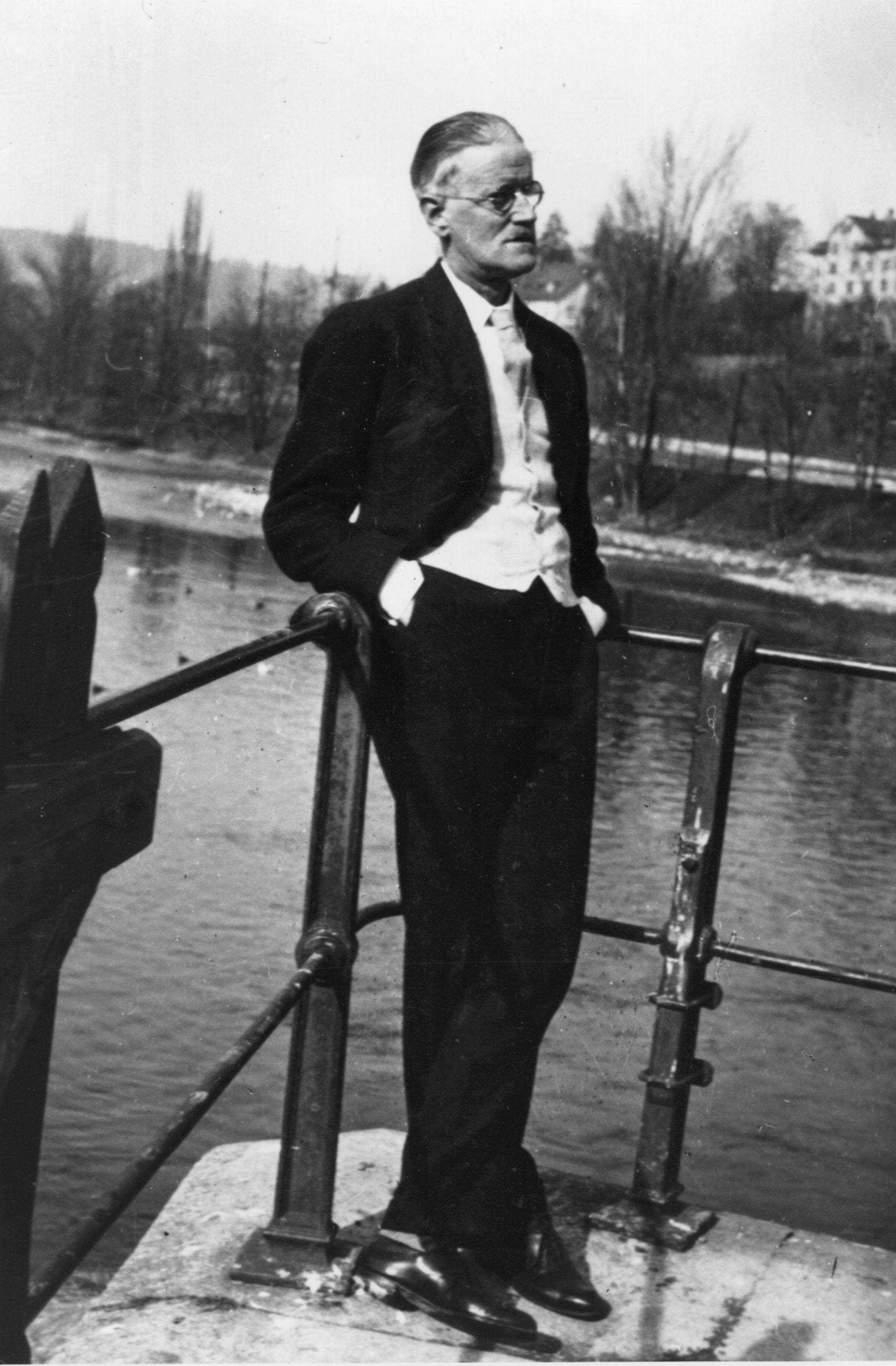

It all began during the First World War, when Zurich became a safe haven for foreign artists and intellectuals, just as it was during the Second World War. Those First World War refugees included Lenin, Einstein and James Joyce, plus a ragbag of international artists, writers and performers who founded the Cabaret Voltaire nightclub, where Dada was born. The club only lasted for a few months, but its influence was immense, inspiring many of the major movements in modern art, and now it’s up and running again.

Hidden down a narrow alley in Zurich’s medieval Altstadt, today’s Cabaret Voltaire is housed in the same building where history was made. Since 2002, it’s been a platform for some of today’s most radical and iconoclastic artists – Jake and Dinos Chapman are among the artists who’ve shown here. Cabaret Voltaire’s director, Salome Hohl, sees some striking similarities between the Dada era and today, not least between Spanish Flu and Covid. “Cabaret Voltaire was always a place of crisis,” she tells me. “It was born in a crisis, to find a new language and to question the language we have.”

After all these years Cabaret Voltaire still feels edgy, and its rebellious ethos is mirrored in the city’s new artistic district, Zurich West. Formerly the city’s industrial zone, its old industrial buildings have been colonised by artists. The Schiffbau shipyard is now a theatre; the Lowenbrau brewery is now a gallery. The Rote Fabrik, a derelict factory on the waterfront, is now an anarchic arts collective. It’s a world away from Zurich’s image as a prosperous, boring city populated by bankers and businessmen, yet Zurich was ever thus – a battleground between financiers and artists.

This kulturkampf was encapsulated in Emil and Emmie’s struggle against Swiss appeasement. It was echoed in the Wohlgroth uprisings of the 1980s, when squatters occupied an abandoned building beside Zurich’s main train station, and painted an enormous sign upon it that read Zureich – too rich – instead of Zurich (what made this graffiti so subversive was that it looked just like official station signage). Eventually, these creative squatters were ejected by Swiss riot police. In the street battle that ensued, some of them took refuge from the teargas in the Oprechts’ bookshop.

Zurich doesn’t like to shout about it, but it’s long been at the cutting edge of modern art and music. The Kunsthaus, Zurich’s municipal art museum, staged the world’s first Picasso retrospective, way back in 1932. The Baur au Lac, Zurich’s poshest hotel, staged the world premier of Wagner’s Ride of The Valkyries – sung by the composer, with Franz Liszt on the piano. From the meisterwerken in the galleries to the murals on the gable walls, avant-garde art is all around you. Yet Zurich prefers to keep it quiet. Elusive and inscrutable – that’s always been the Swiss way.

So what does this story tell us about our own age of intolerance and resistance? That bookish people like the Oprechts often make the biggest difference. That you don’t need to be a loudmouth to change the world. That Zurich, in a way, is a lot like Emil and Emmie Oprecht – quiet and conventional on the surface, brave and bold beneath.

I finished my latest trip to Zurich in the Cafe Odeon, on the corner of Rämistrasse, by the lake. The Oprechts used to come here, and countless writers and artists too: Max Frisch, Stefan Zweig, plus all those Dada pioneers – Hans Arp, Tristan Tzara, Emmy Hennings, Hugo Ball… James Joyce was here, and Einstein, and Lenin, Trotsky and Mussolini. During the 1970s it was stormed by rioters, who damaged its art nouveau interiors. Nowadays it’s a lot more staid, but in Zurich appearances can be deceptive. That nondescript-looking customer might be browsing spreadsheets on his laptop – or he might be the next James Joyce, writing an experimental masterpiece.

“In Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance,” says Orson Welles in The Third Man. “In Switzerland, they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace. And what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.” What an entertaining story. What a shame it isn’t true. Switzerland was a battlefield for 500 years, cuckoo clocks come from Germany, and this unassuming little country has produced more than its fair share of great artists, from Giacometti to Le Corbusier, as well as unsung literary heroes like Emil and Emmie Oprecht.

‘Geta Brătescu x Albert Kriemler. A Collaboration’ is at Hauser and Wirth Publishers HQ and ‘Geta Brătescu. The Gesture, The Drawing’ is at Hauser and Wirth Rämistrasse, 22 October – 21 November 2020, hauserwirth.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks