Gustav Metzger is the most influential artist you’ve probably never heard of

Metzger created auto-destructive art to confront a society determined to destroy the planet. William Cook on an artist-cum-activist who was truly ahead of his time

At Hauser & Wirth Somerset, a sleek art gallery in England’s West Country, a new exhibition has just opened by an artist you’ve probably never heard of – yet his influence has been immense. This man didn’t just shape the course of modern art – he was a pioneer of green politics, and a tireless campaigner against climate change.

A stateless refugee, he lost most of his family in the Holocaust. He arrived in England with nothing, he remained dirt poor throughout his life, and yet he inspired countless artists and activists. So how did Gustav Metzger become such an important figure, when hardly anyone outside the art world has ever seen his work, or even knows his name?

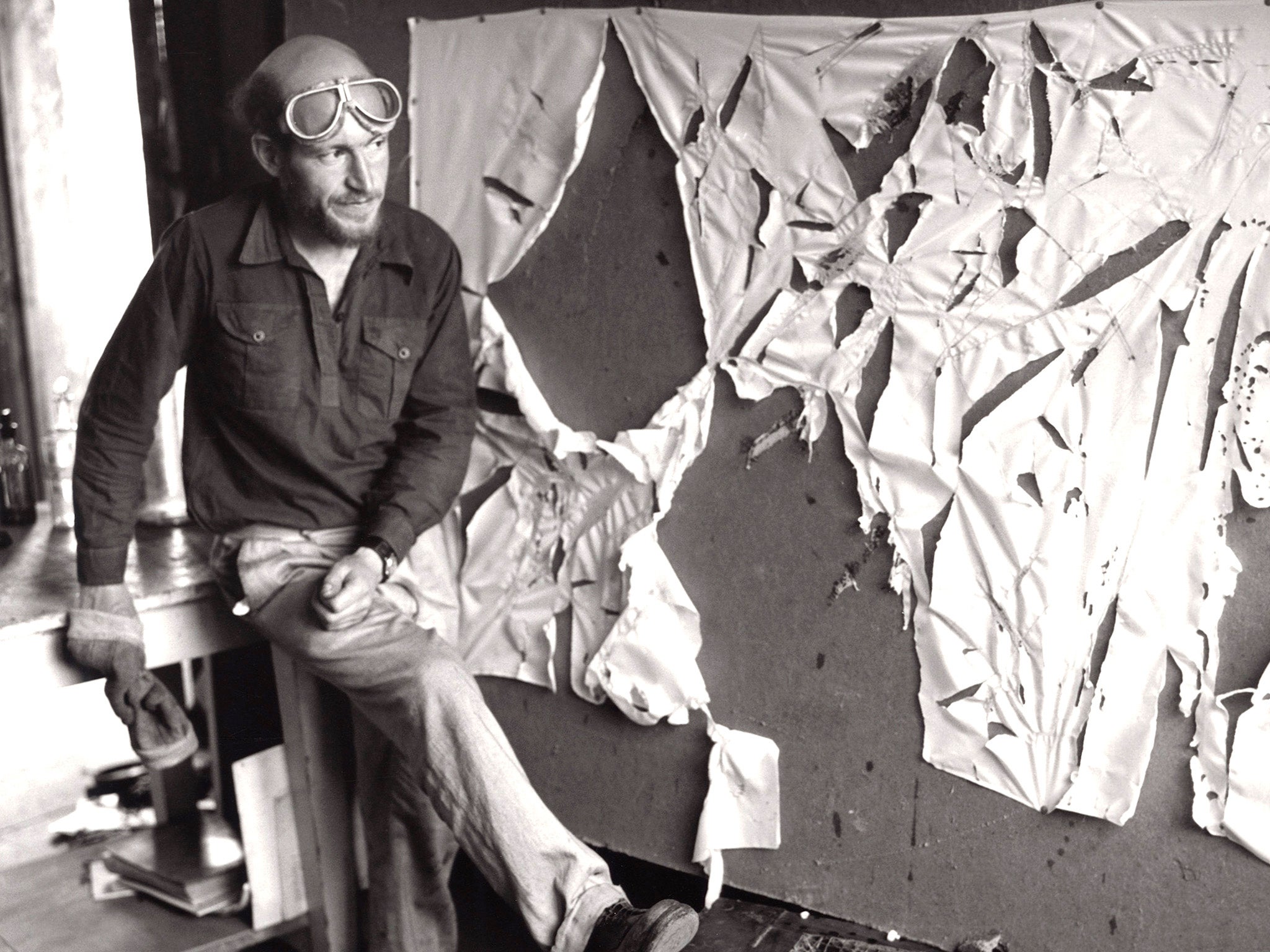

This elusive exhibition provides a few tantalising clues. The first room is a psychedelic light show, like something from a Sixties pop concert. The second room seems more conventional, until you take a closer look. The abstract paintings on the walls are striking, but it’s the tapestry in the centre of the room which really arrests the eye. It looks as if it’s been torn apart by wild beasts. On closer inspection, you realise it’s been sprayed with some sort of acid, which has eaten away at the material, creating a weird otherworldly pattern.

This is a piece of auto-destructive art, an artform Metzger invented as a riposte to the art world. The idea was to create works of art which would automatically self-destruct. It’s a rich irony that this exhibition of his work is being mounted here by Hauser & Wirth, one of the world’s most prestigious commercial galleries, with branches all around the globe.

Gustav Metzger was born in 1926 in Nuremberg. His parents were Polish Jews who’d come to Germany in 1918, in search of a better life (before Hitler came to power, Germany was widely regarded – quite rightly – as one of the best places for Jews to live). That all changed in 1933, but for the Metzgers emigration wasn’t an option. They weren’t wealthy. They ran a modest corner shop. All their money was tied up. Of course, if they’d known what was in store, they would have fled while they had the chance. By the time they realised what was happening, it was already too late.

The Nazis adopted Nuremberg as the venue for their biggest rallies, which gave little Gustav a ringside view of the rise of the Third Reich. As a small boy, he was oblivious to the meaning of these paramilitary rituals. He only knew they were loud and colourful and exciting. On one occasion, as the brownshirts marched down the street, he joined in the procession and got a beating from his horrified, terrified mother. “The impact of the Nazis on me as a child continues to the present day,” he said, 70 years later. “The experience in Nuremberg was very formative for my whole life and for my art.”

By 1938, Gustav’s parents could see the writing on the wall. Kristallnacht (a nationwide pogrom, sanctioned by the Nazi government) had made the situation quite clear. For them there was no escape, but they arranged for Gustav and his brother Max to join the Kindertransport, the British mercy mission which gave thousands of German-Jewish children sanctuary in the UK. They sailed to Harwich in January 1939. Gustav was only 12. He never saw his parents again. They were murdered in the Holocaust, along with his maternal grandparents and his eldest brother, Chaim. As Leanne Dmyterko, co-director of the Gustav Metzger Foundation, says: “From that moment forward, he never really belonged to a place anymore.”

Metzger believed art had been emasculated by the capitalist system, reduced to a mere consumer product. Auto-destructive art was a direct challenge to that

Metzger went to secondary school in London, and then in Hemel Hempstead. In 1941, he left school and went to Leeds to train as a cabinet maker. He worked in a furniture factory, and as a carpenter. When the war ended, he decided to become an artist. However the art that he envisaged was very different from anything that had come before. “The idea that art is something to look at, something in museums, something to hang on a wall, this is something I rebelled against,” he reflected. His art wasn’t about creating objects, to be bought and sold and collected. It was about trying to change society. “It had a social purpose and an ecological purpose,” says Andrew Wilson, who curated a show of Metzger’s work at Tate Britain in 2015. For him, being an artist was a way of life, a state of mind.

From 1945 to 1953 Metzger attended various British art schools. Industrious and talented, his work impressed numerous established artists, but like a lot of gifted students he soon discovered that acclaim is no guarantee of a living wage. He was good enough to get grants to study, but he made hardly any money from his art. And yet he never wavered. The Holocaust had destroyed his childhood, but as an artist it empowered him. As Bob Dylan put it: “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose.”

Alongside his commitment to art, Metzger was an outspoken political activist, and as the Cold War heated up, these two commitments came together. His passionate opposition to nuclear weapons was informed by his experience of the Holocaust. For him, the two were intertwined.

In the late Fifties he was one of the founding fathers of what became the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, organising protest marches to American missile bases around Britain. In 1960 he became a founder member of the Committee of 100, which organised acts of civil disobedience against nuclear armament. In 1961, after refusing to be bound over to keep the peace, he was sent to prison for a month.

“The situation now is far more barbarous than Buchenwald, for there can be absolute obliteration at any moment,” he told the court. “I have no other choice than to assert my right to live, and we have chosen, in this committee, a method of fighting which is the exact opposite of war – the principle of total non-violence.” He made promotional artwork for these protest groups, but his work fused art and politics on a deeper level. British artists were supposed to stay out of politics. Metzger didn’t recognise such distinctions. For him, they were two sides of the same coin.

In the late Fifties and early Sixties, Metzger published a series of manifestos, outlining his theory of auto-destructive art. Metzger believed art had been emasculated by the capitalist system, reduced to a mere consumer product. Auto-destructive art was a direct challenge to that system: canvases ravaged by sulphuric acid, sculptures that crumbled into nothing… how can an artwork have a market value if it’s designed to self-destruct?

It was hardly surprising that many of Metzger’s most ambitious projects never saw the light of day. Who in their right mind would want to fund an artist who wanted to destroy his own work? Yet Metzger influenced all sorts of other artists, who introduced his ideas to a wider audience, especially in the pop world. He befriended Yoko Ono and Paul McCartney. His trippy liquid crystal shows were used in gigs by Eric Clapton’s rock band, Cream. He prompted Pete Townshend’s guitar-smashing antics in The Who (when Townshend was an art student, Metzger was one of his teachers). “He was a visionary,” says Hans Ulrich Obrist, director of the Serpentine Gallery, who mounted a major retrospective of Metzger’s work in 2009. “He always felt that it wasn’t the role of the artist to add objects to the world.”

As an artist, Metzger was way ahead of his time. He foresaw the conceptual art movement of the 1970s. He defied conventional understanding of what constitutes a work of art. His liquid crystal light shows evolved without any input from the artist (he called it auto-creative art). As Dmyterko says: “He used new techniques and methods and materials to do things that artists had never done before.” He showed the way ahead.

While artists like Andy Warhol became pop stars, Metzger kept his head down. He was adept at using the media to promote his message, but he wasn’t interested in personal publicity. For him, the artist was unimportant. The only thing that mattered was the art. As Andrew Wilson observes, auto-destructive art stripped away the ego of the artist. “The artist lights the blue touchpaper, and then the material and the process take over – it’s not about the celebrity artist making their work and taking a bow. It’s about the work itself.”

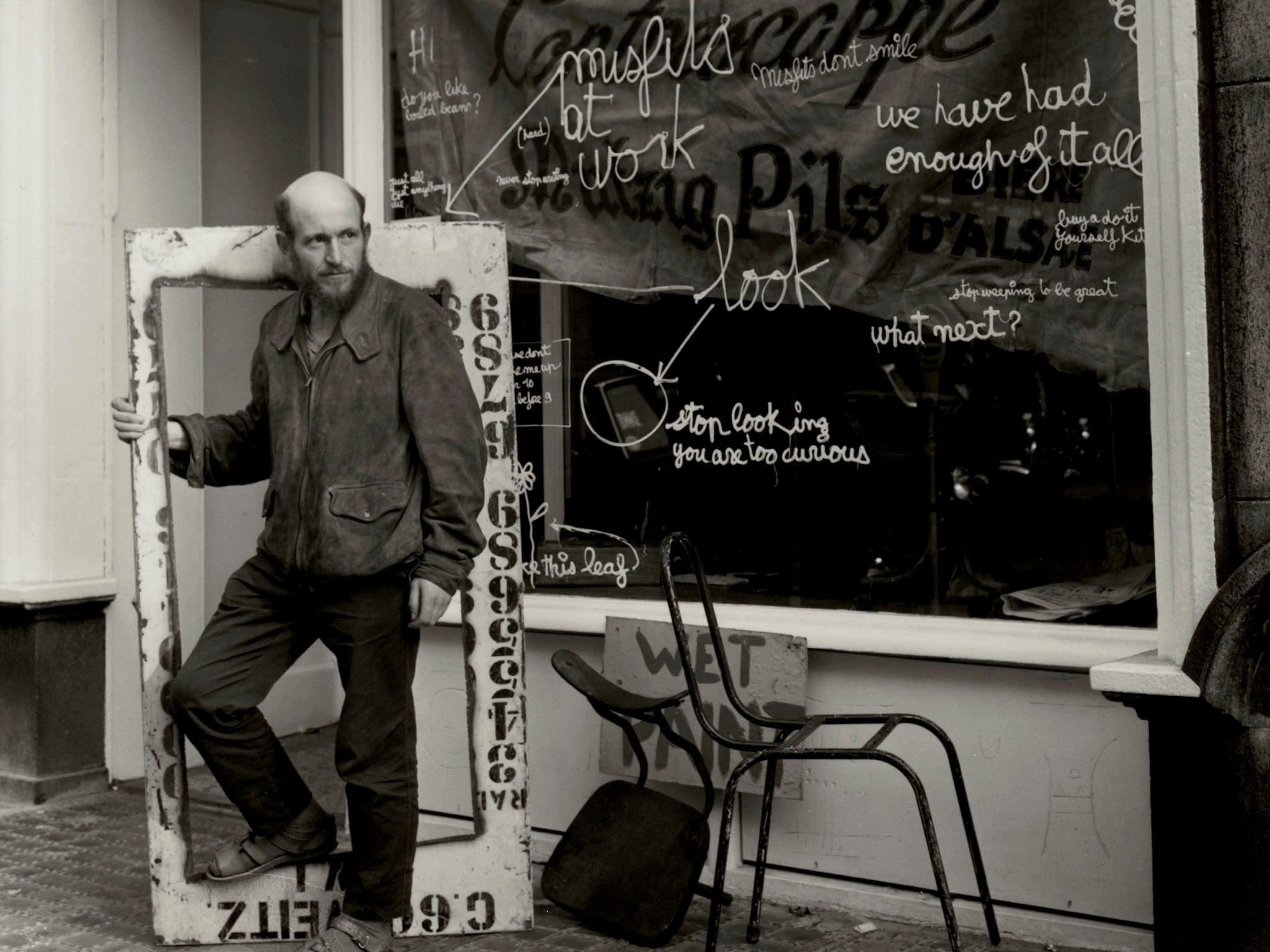

Artists acting individually or in paramilitary units will shoot art dealers, museum officers and art critics. Artists will be invited to enter camps where the making of artworks is forbidden and where any work they produce is destroyed

A lot of the power in his work came from presenting familiar images in unfamiliar settings. For his 1977 artwork, The SunPage 3 Girls, he cut out the topless model from The Sun newspaper every day and pinned it to the gallery wall: one a day, every day, for the duration of the exhibition. Seeing these tabloid images in an art gallery, where you’d least expect to find them, made you look at them in a completely different way. In a later show, he displayed images of the Holocaust in such a way that you had to approach them by crawling under a blanket. Consequently, you arrived at the image on your hands and knees, like a Jew forced to kneel before a Nazi. “What I’m doing is offering everybody the chance to kneel down in front of history,” he explained (this was long before black American sportsmen began to take the knee).

However for Metzger, art was part of the problem. “Artists are dependent on an archaic system of patronage – represented, on the one hand, by the private gallery, which operates for the benefit of market speculators, and on the other hand by the state,” he claimed. “Art today is a monopoly of creativity, a monopoly of knowledge. Art museums are the banks of the art world. Art auction houses are the stock exchanges of art.”

He launched an International Coalition for the Liquidation of Art (“we must liquidate this crazy thing called art, to make it possible for all people everywhere to be creative”) and in 1977 he called for a global art strike, urging all artists to desist from making any art at all until 1980. “This total withdrawal of labour is the most extreme collective challenge that artists can make to the state,” he argued. “Capitalism has smothered art. The deep surgery of the years without art will give art a new chance.” Some of his proposals were pure fantasy, a Swiftian satire on the art world – at least, I’d like to think so. “Artists acting individually or in paramilitary units will shoot art dealers, museum officers and art critics,” he wrote. “Artists will be invited to enter camps where the making of artworks is forbidden and where any work they produce is destroyed.”

This campaign was a colossal failure – hardly anyone else joined in – but it was a fascinating idea all the same. Imagine: if nobody in the world produced any art at all for three years, think how it would reduce our carbon footprint! Think how the power of art to shock and startle would be restored! Undeterred by the lack of support for his crusade, Metzger went on strike, making no art at all from 1977 to 1980. Few people took any notice, but he didn’t seem to care. He called off his one-man strike in 1980, and returned to making art, but he continued to regard the art world as part of a capitalist cabal whose only concern was making money. He campaigned against international art fairs, and the air travel they entailed.

When Metzger called for another art strike, in 1990, he was similarly unsuccessful, but now the ideas behind it no longer seemed so far-fetched. “Civilisation demands a breathing space where people can look back on the cataclysmic changes of the past 200 years,” he wrote. “A winding down of the technological environment, a voluntary abandonment, is the key to survival.” Act or Perish was the title he gave to the Committee of 100 manifesto. It was his misfortune to live long enough to be proved right.

Metzger was most successful as an ecological campaigner. From weapons of mass destruction to the destruction of the rain forests, he confronted a society which seemed determined to destroy the planet. Auto-destructive art was a metaphor for the self-destructive nature of humanity. To simply paint pretty pictures of such obscenities would be pointless. Only an artform which reflected the nihilism of the modern world would do.

Metzger’s ideas are still radical today, but now they’ve gained some traction. “Extinction Rebellion wouldn’t be Extinction Rebellion if it hadn’t been for Gustav,” says Andrew Wilson. Yet now campaigners like Greta Thunberg have become familiar figures, it’s easy to forget what a lone voice he was back then, long before ecology became fashionable. He was there at the beginning. He created a ripple which grew into a tidal wave.

His most potent artworks are ecological: his Mirror Trees, a row of uprooted trees, buried upside down in slabs of concrete (outside the Haus der Kunst in Munich, built to house Hitler’s favourite works of art); his Mobbile, a saloon car driven around the city with a pot plant encased in an airtight capsule mounted on its roof (the exhaust pipe feeds into the capsule, protecting us from its toxic fumes, but killing the plant). Metzger’s book of interviews with Obrist is illustrated with adverts for cheap flights with easyJet et al. Metzger included these ads, without comment, as a statement about low-cost flights in an era of global warming. In isolation, they seem harmless. Displayed en masse, in the sort of book where you’d least expect to see them, the cumulative effect is very powerful indeed.

Metzger wasn’t religious, but his Orthodox Jewish upbringing gave him an ethical and intellectual rigour which endured throughout his life

“There are many dimensions to Metzger,” says Obrist, and that’s what makes him an enigma. In a sense, he wasn’t an artist so much as the ultimate art critic, a man who re-examined western art, and exposed it in an entirely new light: “Art history has been an instrument which upheld the sacredness of art and social institutions. It bolstered the cash and prestige value of collections. It distorted reality and history in order to uphold the status quo.”

Ultimately, Metzger seems destined to be remembered as a philosopher rather than an artist. So many of his artworks have been destroyed, or were never realised in the first place. It’s his ideas that have survived. Mathieu Copeland’s collection of his writings has become a bible for artistic activists. Remember Nature: 140 Artists’ Ideas for Planet Earth (with contributions from Brian Eno, Laurie Anderson, Vivienne Westwood and Yoko Ono, among others) takes its title from the name of one of Metzger’s ecological campaigns. “It was a revolution in art in a very conservative art world,” said Yoko Ono, of his work.

Metzger wasn’t religious, but his Orthodox Jewish upbringing gave him an ethical and intellectual rigour which endured throughout his life. With his ascetic lifestyle and his condemnation of conspicuous consumption (“the co-existence of surplus and starvation”) he resembled an Old Testament prophet commanding rich sinners to repent. As Copeland put it: “Metzger remains a moral compass, a constant reminder that integrity comes at a price, and that fighting for your convictions can indeed change the world.” Like an Old Testament prophet, he sacrificed everything to his vocation. He lived very simply. He was a vegetarian. He didn’t drink. He never owned a mobile phone. “The pathway that he chose was one of extreme difficulty,” says Andrew Wilson. “He didn’t have an easy life.”

Even his close friends knew relatively little about him. “He was incredibly private, in many ways quite a secretive person – I never found out very much about his private life,” says Wilson. “He had relationships with women, but beyond that I think, to a very large extent, you could say he devoted his life to art, to following his calling.” He never married. He didn’t have children. He dated, off and on, but he said he never met the right person. It’s very hard to picture him leading a conventional family life.

Metzger was a shy man, but he was intensely charismatic: driven, determined and utterly sincere. Above all, he was an idealist. “He had a really profound effect on everyone who spent time with him,” says Ula Dajerling, co-director of the Metgzer Foundation. “It completely changed my view of the world.”

“He was quite introverted, but he had this kind of magnetic energy,” concurs Dmyterko.

“He had a seismic impact when you met him,” says Obrist. “It was transformative to be with him.”

Metzger died in 2017, at the grand old age of 90. He kept on working until the very end. “He never gave up,” says Obrist, who last saw him a few weeks before he died. He’s buried in Highgate Cemetery. There’s a Star of David on his grave. The Holocaust robbed him of everything – his family, his innocence, his homeland – yet in a way it made him. It made him fearless. It made him realise that our capacity for destruction is limitless. It made him determined to warn the rest of us, to share that realisation with the world. And in the end, what could be more important than that?

Gustav Metzger is at Hauser & Wirth Somerset to 12 September 2021 (hauserwirth.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks