A brief history of turtle soup and its role in ensuring we protect turtles today

Ahead of World Sea Turtle Day, Ashley Coates looks at how a fondness for turtle meat led to a global industry and turned a once common sea creature into an icon of conservation

Interfering with turtles today can land you in a lot of trouble. The urge to play with them is too much for some tourists but can carry a hefty fine, as two US citizens found out in 2017.

After posting an image with a turtle captioned: “Missing the time we risked a $20,000 (£15,700) fine to catch a sea turtle with our bare hands”, they were roundly criticised on social media and fined within the actual limits of the US Endangered Species Act – $750 for picking up a Hawaiian green turtle.

It is a remarkable change in attitude considering it wasn’t long ago turtles were a central ingredient in a tomato-based soup that was hugely popular in many parts of the world, particularly the US, UK, the Caribbean and China.

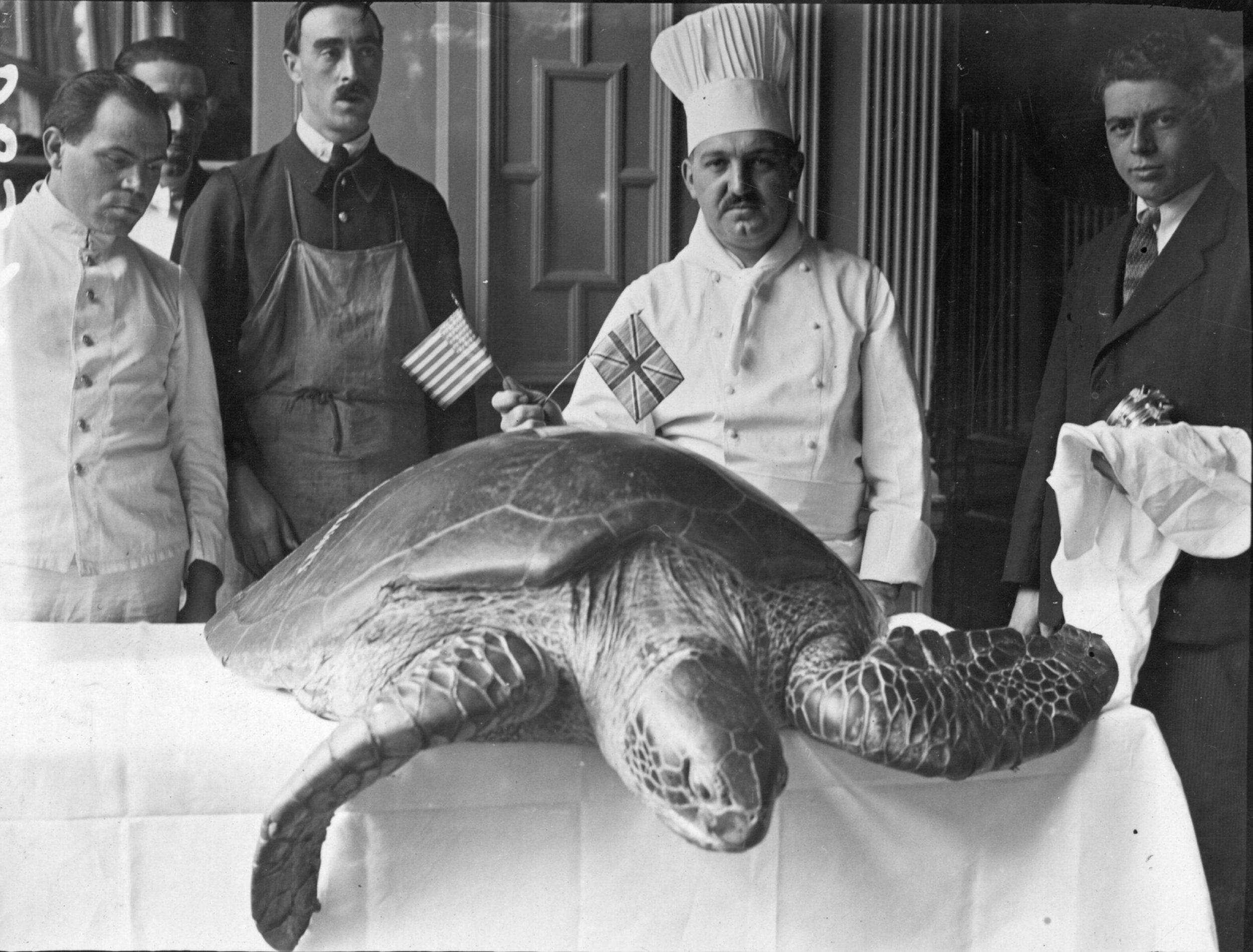

Turtle soup was a favourite of royalty and presidents, with William Howard Taft keeping a specialist chef on White House payroll who knew how to prepare a dish known as “Taft Terrapin Soup”.

The Taft soup was made with one whole turtle and four pounds of veal. Such was the esteem with which Taft viewed his own version of the soup, it was regularly prepared for important visitors and he insisted his soup had to be served with champagne. George Washington and John Adams both served turtle at the White House, while Abraham Lincoln is known to have offered up terrapin hors d’oeuvres at a dinner following his second inauguration.

Some of the 19th century’s biggest fans of turtle soup became the first subscribers to one of America’s oldest social clubs – the Hoboken Turtle Club, which carried the motto Dum vivimus vivamus, “while we live, let us live”.

“It was really an aspirational dish,” Dr Ruth Thurstan, lecturer in biosciences at the University of Exeter, tells me. “It was considered an exotic, high-class dish, associated with the upper classes. It just so happened that it tasted good as well, it was highly nutritious and not too far off our own palette at that time.”

For much of the 1700s and 1800s, turtle was a delicacy for the middle and upper-middle classes in England, something you might serve to impress your guests or to have on a particularly special occasion. Writing in her early journals, Queen Victoria said turtle soup was in the same category as “insects and Tories” when it came to things she didn’t like in the world, but later in life she warmed to the dish to the point where Hatfield House would lay on £800 worth of turtle during a three-day visit by the Queen.

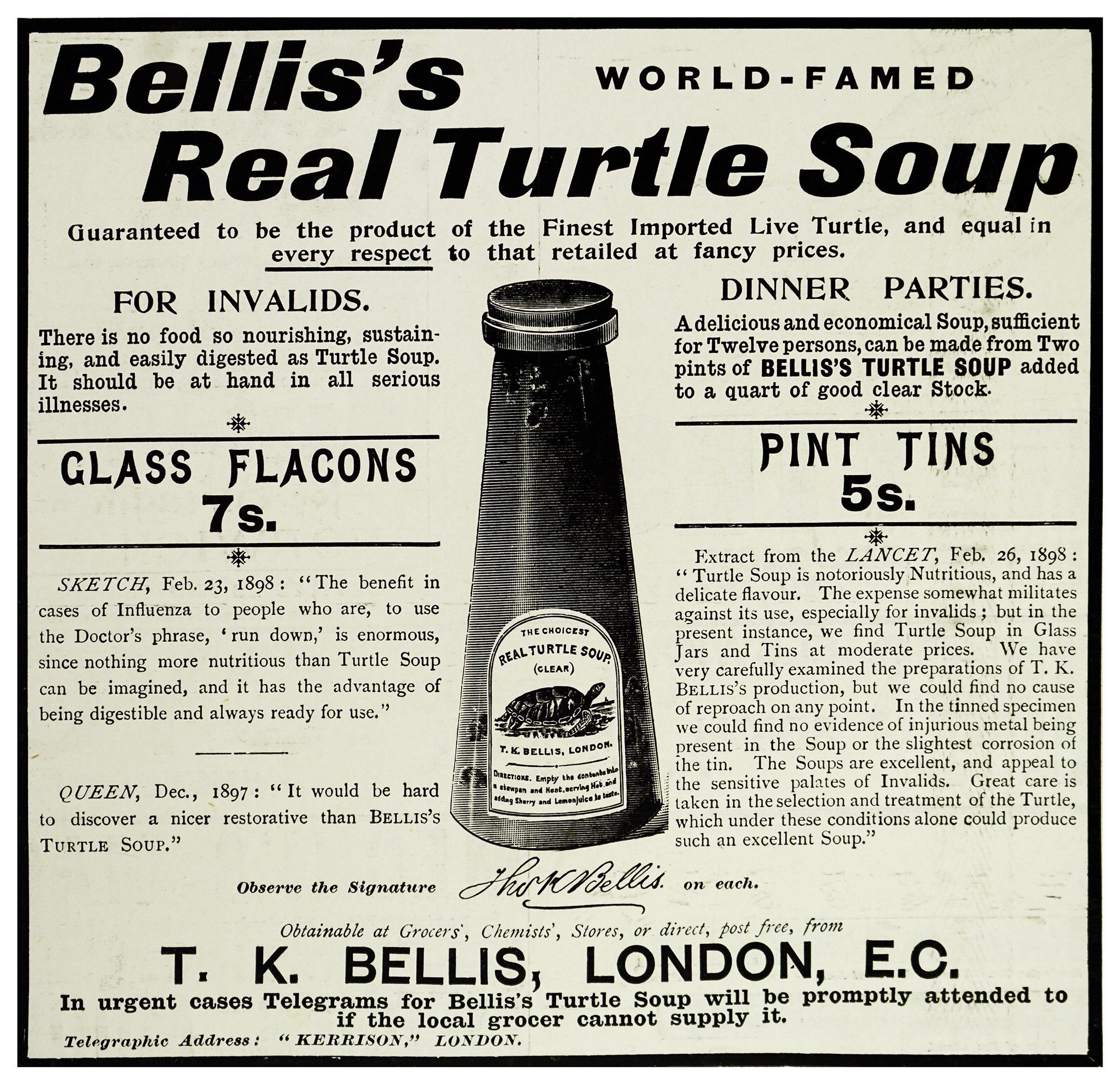

Victoria was supplied by a man colloquially known as the Turtle King, a Liverpudlian who carved out a niche for himself as an importer of live and processed turtles, which was mostly a species called the green turtle. According to an 1898 edition of The Sketch, Thomas Kerrison Bellis’s firm was importing as many as 100 turtles per week in the late 1800s, all on steamboats equipped with salt water hoses to help keep them alive during the voyage. Those turtles that did survive the journey were quickly processed or sent on to their high-end banqueters alive.

Their survivability on long voyages is one of the reasons why turtles became such a popular food. As early as the 1500s, turtles were prized by sailors as easy sources of protein as they could survive journeys on European vessels returning from the Caribbean. The ones that did reach mainland England were of high interest to royalty and the aristocracy, who paid over the odds for turtle, often preparing a broth and using the shell as a bowl.

For all the Victorian ingenuity demonstrated by the likes of the Turtle King, the turtle supply chain wasn’t always reliable, as the elite diners of London discovered in January 1905, when a dispute between Nicaragua and a group of fishermen resulted in a total absence of turtles for cooking in London. A copy of the West Gippsland Gazette read: “DEARTH OF TURTLES – BANQUETERS IN DEEP ALARM”, before going on to note the “amazing restorative properties” of products derived from turtle, including the advantages consuming turtle meat had for battling influenza and a range of other diseases.

They weren’t just useful for their meat – turtles were also used to make leather products such as purses and shoes, their shells have gone into jewellery, hair clips and buttons, while turtle fat was used in soaps and make-up products. Sadly, some of this trade continues to this day, illegally.

“They have always been important for food, but hold a cultural and spiritual significance for many cultures,” Brendan Godley, professor of conservation at the University of Exeter, says.

“Turtles had an importance in dowries, with the bekko trade (trade in shells) being especially important in places like Japan. The Cayman Islands were essentially founded on sea turtle harvests. It was their major industry right up until the 1950s. It is on the national arms, their currency, the logo for the electric company, the tails of the planes.”

Partly due to the difficulties in getting hold of turtles, mock turtle soup emerged as an appealing alternative in the 19th century and was even preferred by some diners. This was essentially the same as turtle soup but with offcuts of chicken or calf’s head substituting the flesh of sea turtle and proved to be a considerable commercial success.

For the British and American consumer, there was a brief period where the tinned food isles included a now lost product – the canned form of mock turtle soup, which was largely discontinued in the Sixties.

In the 20th century, Andy Warhol was among the many fans of the “mock” version of the soup, but it was Lewis Carroll who put mock turtle soup firmly into our cultural heritage. “I don’t even know what a mock turtle is,” Alice says in chapter nine of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The Queen of Hearts replies: “It’s the thing mock turtle soup is made from.” And so the mock turtle is revealed, a bizarre creature with the head of a calf attached to a turtle’s body, who is sad because he once used to be a real turtle.

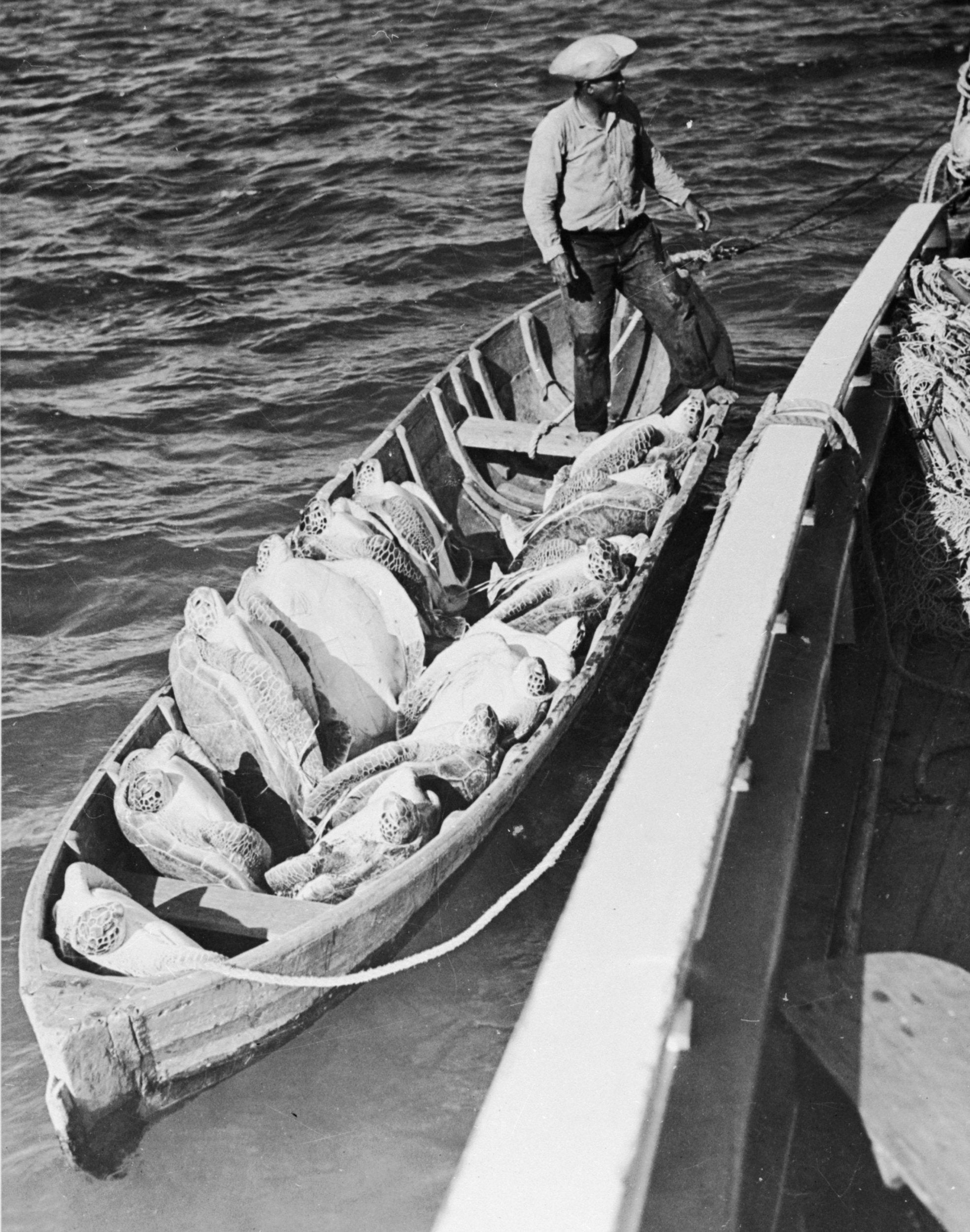

By the 1920s, “real” turtle soup in cans started to be sold in everyday shops, with firms such as Campbell’s and Heinz rolling out canned turtle. It brought a meat that was once the preserve of the upper classes to the masses, but also spelled the end of turtle as a food product.

The industrialisation of turtle fishing had reduced their numbers drastically. Their fate was similar to that of the whales, they had gone from one of the most common large animals in our oceans to one of its most endangered and vulnerable. While the total catch made in the final years of whaling was followed closely by scientists and statisticians, the final years of the large-scale turtle trade were not reported in as much detail.

What finally put an end to the industrial turtle trade? According to Brendan Godley: “Their populations had taken a real hammering and had decreased massively by the middle of the last century, but the real thing that stopped it all was the advent of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites). Once you had Cites, you couldn’t trade these products internationally.

“The Cayman Turtle Farm was selling turtle soup until the 1980s, but Cites meant they were left only with their domestic market.”

So the turtle “industry” was largely wrapped up as a result of a far-reaching multilateral treaty – but just how big did this trade get? In the last few years, researchers at Exeter have been trying to put together the numbers of turtles traded worldwide. This is still a work in progress but the figures that have been established so far confirm that fishing for turtles was taking place on a truly industrial scale, even during the end of the last century.

According to Ruth Thurstan’s team, 2.2 million hawksbills were traded from the Pacific-Asia region alone between 1950 and 1999. The hawksbill, whose ornate shells were used to make musical instruments, jewellery and eye-glasses frames, is now critically endangered. The green turtle that supplied the meals of so many of the great and good is now listed as endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. Both species are threatened by illegal hunting to this day.

Turtles are now icons of the conservation movement, what biologists call “charismatic megafauna”, and are often used to garner support for better protection of the world’s oceans. Much like the whales, sea turtles went from being viewed as a valuable commodity to a much-loved and revered animal, deserving of the highest levels of protection.

Unlike the whales, however, the story of our exploitation of the turtle is not widely known.

“It seems to have been lost from our cultural memory,” Thurstan says, “I don’t think many people know how big turtle was as a food, particularly in this country.

“It was so closely associated with gentry and refinement for many, many years, and became a core part of the lives of people, often trying to appear to be better off than they were. What has surprised me is how quickly turtle appeared and then disappeared and how quickly the trade has gone from our memory.”

Today, the “most endangered turtle” is widely considered to be the Yangtze giant softshell river turtle, the last female of this species died in captivity in April. It is a particularly big loss as the under-developed shell structure connects today’s living species with the very first turtles, which are thought to have evolved from lizard-like creatures around 260 million years ago. With the loss of the last female, it is now highly likely that this species will follow the Yangtze river dolphin in becoming another Chinese species to die out due to hunting and habitat loss.

Despite their relatively precarious position today, turtles are one of the world’s great survivors. Like the sharks and the crocodile, they have been roaming the world well before the first dinosaurs.

The earliest turtles are thought to have evolved during the late Permian period, 298 to 251 million years ago. They have remained largely the same physiologically, with no outside pressures forcing them to drastically adapt, even through the mass extinction at the end of the Permian, which wiped out 90 per cent of life, a smaller extinction event at the start of the Jurassic and another high-impact event at the end of the Cretaceous, where 75 per cent of species were lost.

Eunotosaurus africanus is our earliest known turtle. Dating from about 268 million years ago and first described by scientists in 2015, it would probably have looked like “a strange, gluttonous lizard that swallowed a small Frisbee”, according to the people who found it. Eunotosaurus had a much longer tail than modern turtles and still had the teeth that would be lost in later turtle species. A hardened shell (carapace) would evolve later, for now, it only had the outline of a shell, perhaps similar to the very rare soft-shell turtles we still see today.

The end of the Cretaceous period not only saw the extinction of all the non-avian dinosaurs, but also the last of highly successful marine reptiles that had dominated the seas over the previous 100 million years, the dolphin-like ichthyosaurs, long-necked plesiosaurs and tyrannical mosasaurs. Yet the turtles continued.

The mass extinction created by human actions, now known as the Anthropocene, has proved to be more challenging for these great survivors. To the surprise of some, there is still a legal turtle harvest of around 42,000 turtles per year and turtle soup still appears in some parts of the world, but for Godley, this is not the biggest worry for the preservation of today’s turtles. “The focus is often on relatively poor people taking turtles to eat, but many more die as a result of people fishing for tuna and shrimp,” he says.

“The most significant threat is accidental capture in fisheries, that can be on huge industrial wall-liners but also in artisanal fisheries.”

Yet it is not all bad news. “Many populations are now rebounding,” Godley says. “In fact, more populations are increasing than decreasing. This is because there is active protection around nesting areas and no large-scale fishing of turtles.”

While our ancestors might have laid on turtle soup to impress their guests, now you can be fined hundreds of pounds just for touching one.

Twenty-first-century threats to turtles are more inadvertent, illegal hunting continues, but habitat loss (particularly of seagrasses), plastic pollution and accidental capture in fishing nets have emerged as more significant threats.

World Sea Turtle Day (16 June) was established “to honour and highlight the importance of sea turtles”. It may also be worth using this day to remember a forgotten industry. Turtle went from small-scale fishing by individual fishermen to providing soup for the well-heeled or well-connected, and finally to industrial over-exploitation, with turtle appearing in cans at the supermarket.

The industrialisation of turtle fishing, the crash in turtle numbers, and the sudden demise in turtle as a food product in the western world happened within a few decades. It is an important part of our environmental history and something that is worth us being more aware of. Having a better idea of how we used to treat the animals we now love can give us a different perspective on our attitudes today. What are we doing to the oceans now that will appear to be unacceptable in just a few decades time?

If we are to secure a future for turtles, the great survivors that have weathered multiple extinctions, we need an even greater attitudinal change to the way we treat all our oceans and the life they support.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks