The Tom and Jerry wars: How acrimony between the cartoon’s producer and its animators was key to its success

MGM cartoon boss Fred Quimby used to take all the credit for Joseph Barbera and William Hanna’s cat-and-mouse stories. As the new Tom and Jerry movie hits screens, Geoffrey Macnab looks at how resentment can be good for creativity

You can see the footage of the old Oscars ceremony online. The master of ceremonies beckons glamorous star Jeanne Crain to the microphone to present the 1949 short film award. When she announces the winner – the Tom and Jerry cartoon The Little Orphan – a stocky, middle-aged man in a bow tie clumps his way inelegantly to the front, brusquely takes the statuette and quickly disappears backstage. There is no speech or acknowledgement of any of his collaborators.

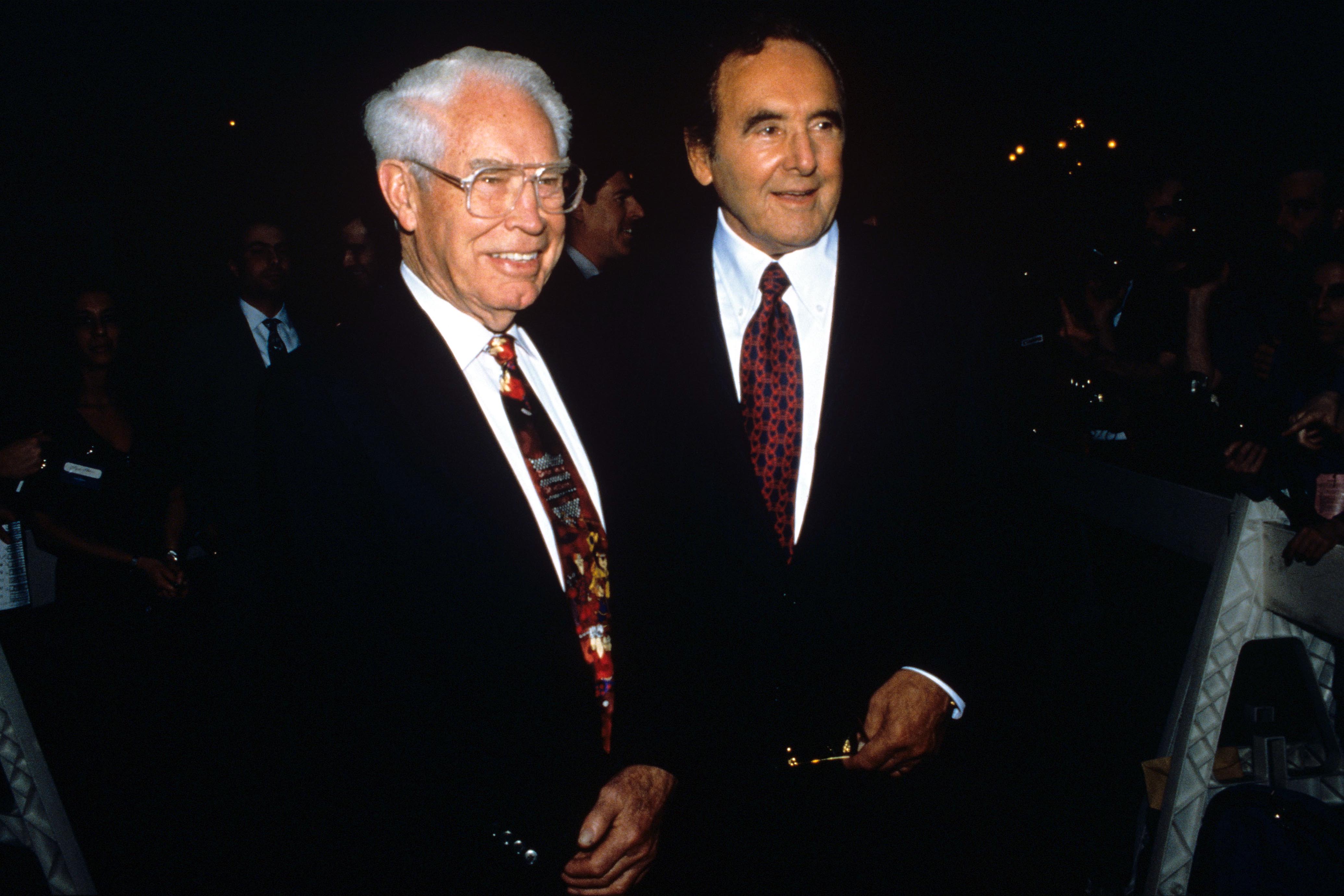

This happened many times over the years. The man who made off with the Oscars was Fred Quimby, the head of MGM’s cartoon department. From 1943 to 1953, Tom and Jerry shorts, written and directed by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, won seven Academy Awards, but Quimby, as the producer, hogged the limelight… and all the statuettes.

“Quimby used to walk up on the stage, take the Oscar, never say a word and leave. It was highway robbery,” Barbera later complained.

Eighty years after the first Tom and Jerry cartoons were made, and as a new film featuring the cat and the mouse is released in the UK this week, it’s a timely moment to look back at one of the most fraught collaborations in the golden age of American animation.

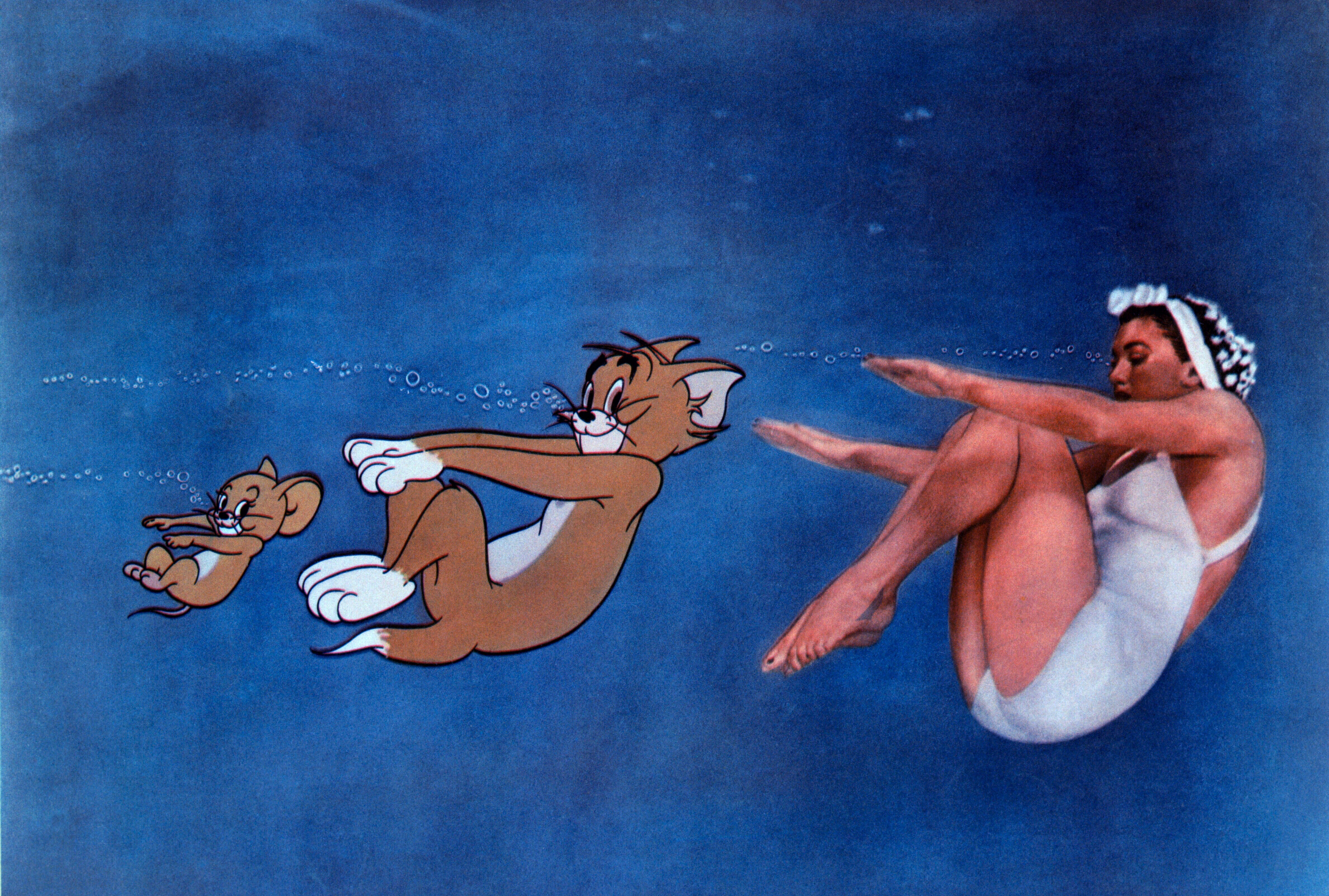

On the Tom and Jerry cartoons, Quimby’s “produced by” credit was always the biggest. It was the last one too, and therefore the name most likely to stick in audiences’ minds. As the animated characters’ fame grew and they were featured alongside live-action MGM stars like Gene Kelly in Anchors Aweigh (1945) or wearing flippers with Esther Williams in an underwater sequence in Dangerous when Wet (1953), Quimby was always there to take the plaudits. The public was convinced he was behind the cartoons they so enjoyed.

Read more:

When Quimby died aged 79 in September 1965, the obituaries referred to him as an “artist” and “the creator of the Tom and Jerry series”.

In fact, as Hanna and Barbera would tell anyone who would listen, the Tom and Jerry cartoons had come into being in spite of Quimby, and definitely not because of him.

Quimby was a former film salesman who had run the short film department at MGM since the mid-1920s. According to those who worked alongside him, he had no creative instincts whatsoever. He was a dour business executive who wore smart, double-breasted suits but whose attempts at suavity were severely undermined by, as Barbera later wrote, “ill-fitting dentures and an abundance of loose jowl”. Animation historians like Leonard Martin talk about his absolute lack of a sense of humour.

The attrition between the MGM animators and Quimby wasn’t entirely surprising, and similar dynamics existed elsewhere in the industry. Art Babbitt, one of Walt Disney’s most talented and best paid artists, loathed his boss too. When Disney’s lower-paid employees went on strike in 1941, Babbitt lent them his support.

In the case of Hanna-Barbera vs Quimby, the hostility was very long lasting. You could still find Barbera in interviews late in his life, complaining bitterly about his old boss’s “outrageous” underhand tactics on Oscars night.

In their accounts of working with Quimby, Hanna and Barbera cast themselves as the plucky little mice and their boss as the lazy, predatory cat. They remembered the studio’s indifference bordering on hostility when they conceived their first cat-and-mouse story, Puss Gets the Boot, in 1940 – in which the cat was called Jasper and the mouse wasn’t named at all.

“We were greeted with a universal chorus of jeers and raspberries. ‘A cat and a mouse! How unoriginal can you get? And how much variety can you milk out of such a hackneyed, shop-worn idea?’” Barbera described the complete lack of enthusiasm the animation studio showed for the idea. Quimby, though, eventually left them to their own devices. He didn’t “know enough” to interfere and wanted to keep his distance from what he was convinced would be a failure anyway. The attitude was “let them [Hanna and Barbera] sink slowly into the mud”. Quimby wasn’t even the producer, leaving that task to Rudolf Ising.

To everyone’s surprise, Puss Gets the Boot was nominated for an Oscar and turned into a sizeable hit. Audiences loved the cartoon, which was very different to both the sentimentality of the Disney shorts and the zany surrealism of Warner Bros’ Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes.

Further cat-and-mouse films were eventually commissioned, although Quimby initially told the animators he “didn’t want any more pictures with the cat and the mouse” and only changed his mind to placate an important distributor.

The first official Tom and Jerry story, The Midnight Snack, was released in 1941. Jasper was ditched and Hanna and Barbera invited their colleagues to come up with alternative pairs of names and put them in a hat. Animator John Carr submitted “Tom and Jerry” and won the $50 sweepstake. By then, Ising had been sidelined, ironically on the grounds that he didn’t contribute enough, and Quimby had begun to slap his own name on the cartoons as the producer.

It might be overstating it to suggest that the longevity of the series is rooted in its creators’ antagonism toward their boss. Nonetheless, Quimby inadvertently inspired Hanna and Barbera. He stole their credit, paid them what they thought was a pittance and stoked their many grievances. They reacted with a manic inventiveness, driven by resentment. A further edge came from the animators’ rivalry with Walt Disney, whom they felt to be high-handed, sanctimonious and condescending. Beating him to Oscar nominations and awards gave them the same pleasure that Tom used to take when, say, he had just electrocuted Jerry, shot a firework down his throat or lit a stick of dynamite beneath his tail.

The cartoons had an unsavoury element. Some broadcasters in recent years have carried health warnings about Tom and Jerry’s “ethnic and racial prejudices”. In particular, the stereotypical depiction of the black maid Mammy Two Shoes has been widely criticised.

Researchers also called attention to the excessive violence in the shorts. Psychiatrists have suggested that young children may be inspired to copy the characters because “Tom and Jerry constantly hit each other and no one dies”. In 2016, an Egyptian academic blamed the cat and the mouse for the rise in sectarian violence in the Middle East.

However, the best Tom and Jerry cartoons were inspired affairs: concentrated exercises in comic, sadomasochistic fury. Generally six or seven minutes long, they were ingenious in their visual gags, relentless in their pacing, beautifully crafted and very funny.

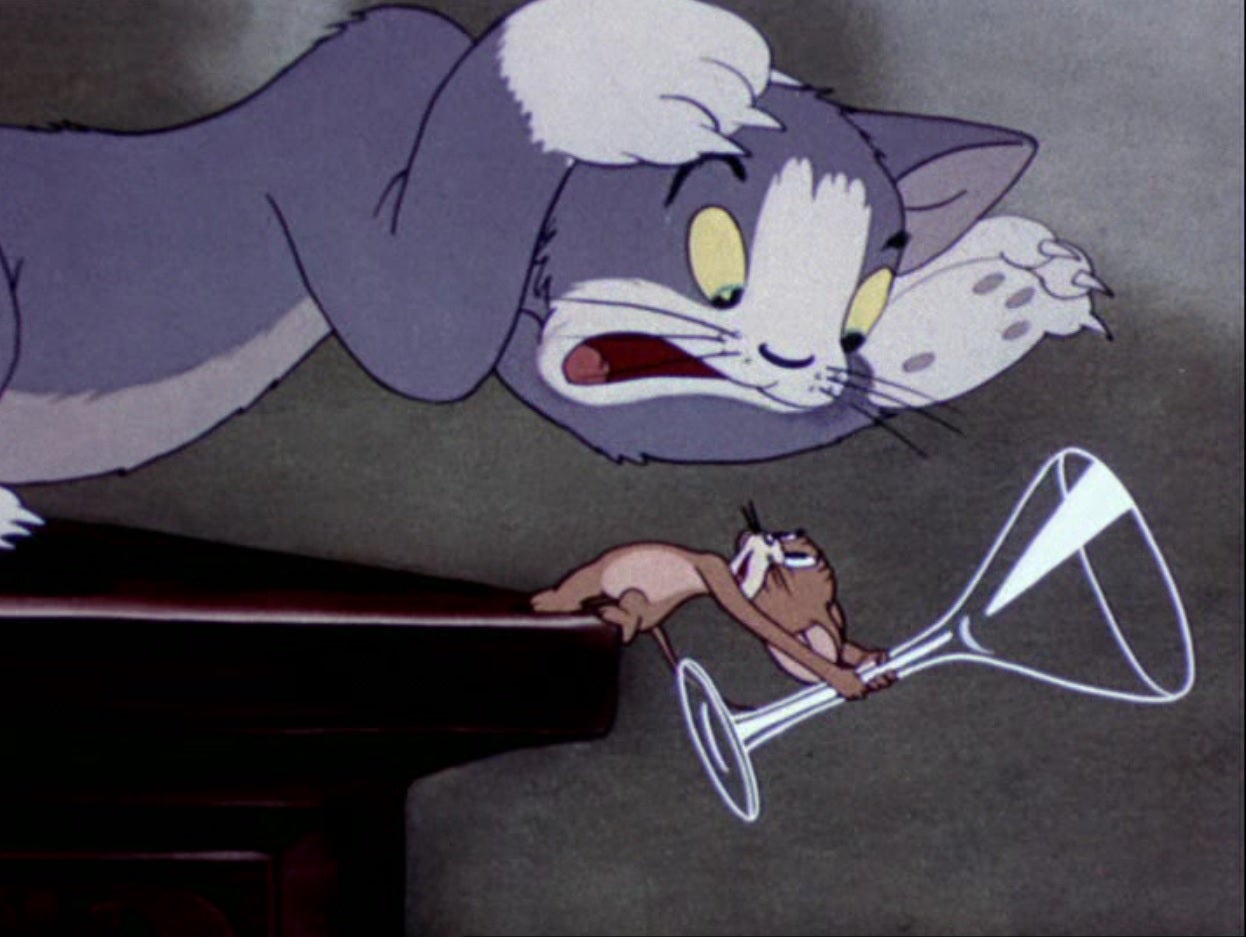

These qualities were evident right from the start. In Puss Gets the Boot, the feral, malevolently grinning cat takes a fetishistic pleasure in tormenting the mouse. Then he smashes a precious vase and it becomes his turn to suffer. The maid warns him that “if he breaks one more thing”, he will be thrown out. That gives the mouse licence to tease and blackmail him. If the cat reacts, all the mouse needs to do is push a precious plate or cocktail glass off a table. The cat will get the blame. There is nothing cosy or maudlin about the storytelling. The humour comes from the ingenious way in which the creatures inflict pain on one another.

By contrast, the new feature film out this week, from Fantastic Four director Tim Story, is sanitised and disappointingly bland. Combining live action with animation, it stars Chloë Grace Moretz as Kayla, a young con artist who wheedles her way into a temp job at a top New York hotel. She is assisting in the preparations for a huge wedding. Mischievous mouse Jerry has also taken up residence in the hotel and is causing chaos. In desperation to save her job, Kayla recruits out-of-work feline musician Tom to hunt the little rodent down.

The live-action and cartoon elements don’t sit at all comfortably together. The rap music and references to social media shoehorned into the script to give it a contemporary feel don’t help. Story, who has never handled animation before, has talked about putting Tom and Jerry on “a much bigger canvas”, as if expanding the environment, moving them out of a house and into a huge hotel, will add to the richness. In fact, it simply makes the storytelling more diffuse. The chases and fight scenes are as hectic as in the original animated shorts but their impact is diminished by the weakness of the plotting. Whereas the cartoons provided short, sharp shocks, the feature film version is rambling, unfocused and only partially salvaged by its main explosive set-piece, the wedding party at which everything goes wrong.

In the credits, Hanna and Barbera are fully acknowledged. For once, Quimby isn’t mentioned at all – and there is no reason why he should have been. Maybe, though, he is the missing factor. The filmmakers behind the new film might have been galvanised to make a far better and more lively movie if they too had had a boss they despised.

True to form, Quimby showed no loyalty to Hanna and Barbera. When he retired because of ill health in 1956 and allowed the duo to take charge of the MGM animation studios, he left them in charge of a sinking ship. By then, Hollywood was struggling to compete with TV. Cartoons were considered far too expensive and time-consuming to keep on making. There weren’t to be any more Oscars. Again, though, Quimby’s callous treatment of the animators was ultimately to their advantage. They were forced to refine their technique, making cartoons for TV cheaply and quickly. It paved the way for the glory years of Hanna-Barbara: for Huckleberry Hound, The Flintstones, Scooby Doo, Top Cat et al.

The two animators’ contempt for Quimby lasted the rest of their lifetimes but, in more reflective moments, the duo must surely have acknowledged that without their infuriating old boss to react against, they might never have scaled such heights.

‘Tom and Jerry’ is released on VOD on 25 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks