The return of Indiana Jones: Can he survive without Spielberg?

Production is shortly to begin on Indiana Jones 5, with James Mangold taking over from Steven Spielberg as director. Geoffrey Macnab is not convinced, however, that the magic of the franchise can be maintained much longer

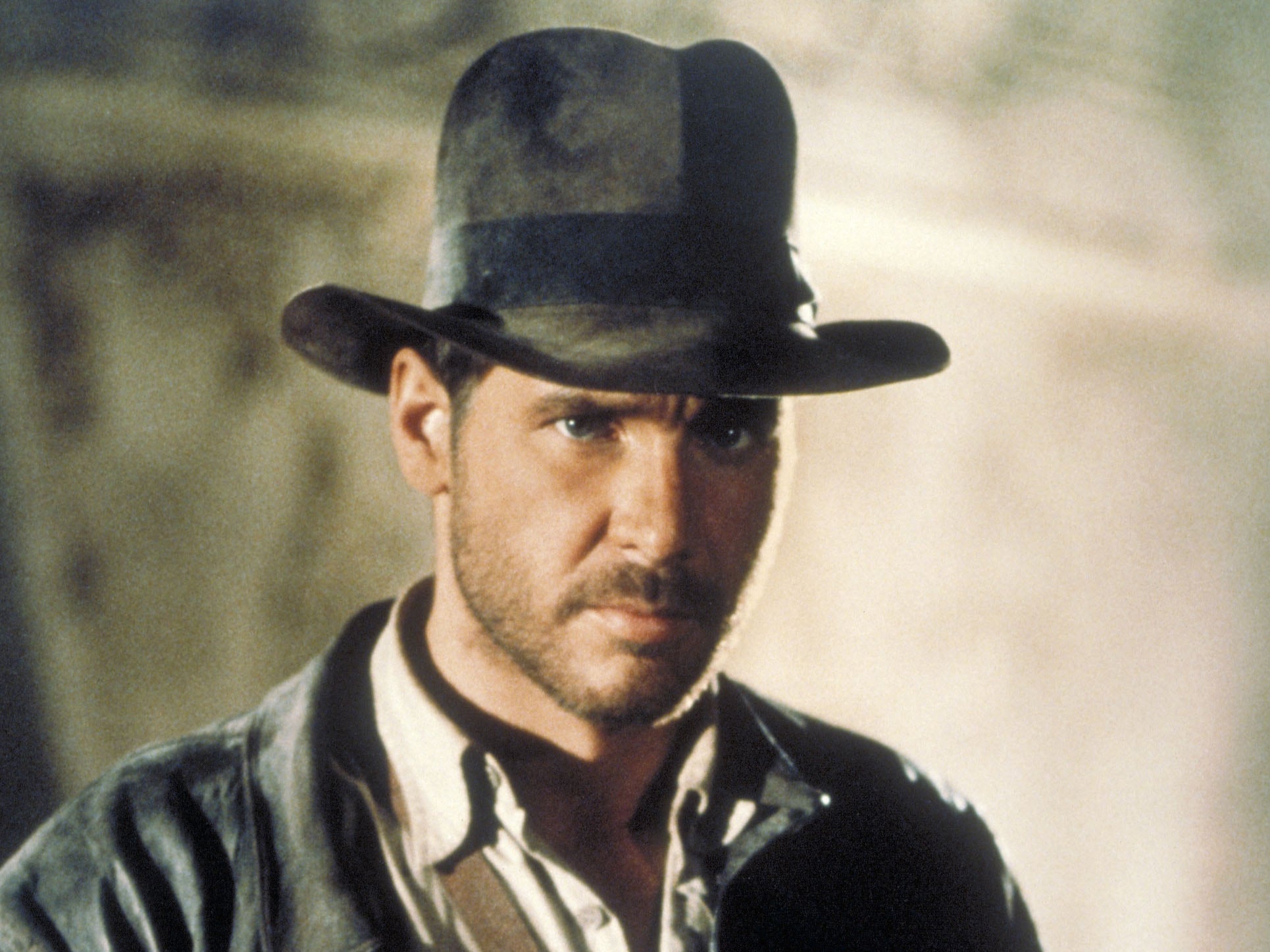

Details are being kept under lock and key but what is now known for sure is that that the fifth Indiana Jones movie is soon to start shooting at Pinewood Studios. At the ripe old age of 78, Harrison Ford will be back in that faded old leather bomber jacket. We’ll hear the rousing John Williams music once again, although, this time, Steven Spielberg won’t be directing. That task has fallen to James Mangold, the filmmaker behind the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line and the full throttle motor racing drama, Ford v Ferrari. Spielberg will executive produce. A release date has been set for July 2022.

The question is whether the new film really is such a good idea. There must be a danger the series’s legacy will be tarnished by an unneeded late addition. Will Mangold have the lightness of touch, ability to improvise, zany humour and sheer relentlessness that Spielberg brought to the original Indiana Jones films?

We can expect that Ford will give a performance similar to that of Sean Connery as Professor Henry Jones, Indiana’s father, in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). Which is to say, he will use cunning and comic timing to make up for his declining powers of athleticism. The main stunts will be left to a younger co-star, whose identity is yet to be revealed. (Ford seemed to suggest in a recent interview that Chris Pine will be involved in some capacity.)

It is 40 years now since Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), the first film in the cycle. On a beach holiday, Star Wars creator George Lucas had famously mentioned in passing to Spielberg that he had a project “about an archaeologist-adventurer who goes searching for the Ark of the Covenant”. When Lucas added that the story was “like the old serials” and that the hero would “wear a soft fedora and carry a bullwhip”, Spielberg, as he told biographer Joseph McBride, was “completely hooked”.

Exhaustive attention has been paid to the Raiders conception story. Lucas and Spielberg recruited advertising writer Lawrence Kasdan to work on the screenplay. They brainstormed together, drawing on John Ford westerns, Kurosawa samurai movies, Casablanca, old Howard Hawks screwball romances, Flash Gordon adventures, Zorro, Tarzan and almost anything else that sprang to mind. The film would be set in the mid-1930s. There would be Nazi villains, mysticism and slapstick.

Just over a decade ago, a transcript emerged of a 1978 story conference to discuss the project, then called Indiana Smith. “It’s a spaghetti western, only it takes place in the Thirties. Or it’s James Bond and it takes place in the Thirties. Except James Bond tends to get a little outrageous at times. We’re going to take the unrealistic side of it off, and make it more like the Clint Eastwood westerns. The thing with this is, we want to make a very believable character…,” Lucas remarked blandly about his ideas for Indiana Jones. His words, though, were treated by fans as if they were gnostic prognostications from some mystical seer.

Harrison Ford was cast in the lead role primarily because the first choice, Tom Selleck, the ruggedly good-looking star of TV show Magnum PI, wasn’t available and Nick Nolte wasn’t interested. The filmmakers went to great lengths to distinguish the character from Ford’s Han Solo in Star Wars as they certainly didn’t want the new movie to be seen as having anything to do with that galaxy far, far away.

Read more:

Pearl Harbour at 20: Was it really as disastrous as reviews made out, or has it improved with age?

Harassment, public scandals, falls from grace: Who wants to be a movie star?

Fangs, lust and coffins: 100 years of vampires on screen

On paper, the film must have seemed juvenile and self-indulgent in the extreme. This was a boys’ own, wish-fulfilment fantasy – a big-budget movie rooted in its two main creators’ shared obsession with cheesy, lo-fi B-movies and serials. Nonetheless, thanks to their alchemical cinematic powers, Raiders turned into the top grossing film of 1981. It was regarded by critics as an instant pop-culture classic and by audiences as one of the most entertaining films they had ever seen.

Raiders of the Lost Ark has aged remarkably well, its occasional moments of jingoism notwithstanding. It is one of the few films from its era that has remained in constant circulation ever since. By a neat irony, a picture predicated on nostalgia is now itself an object of that same nostalgia. Just as Spielberg and Lucas looked back to 1930s serials and matinee adventures with such pleasure, fans regard Raiders with a similar indulgent affection when they remember the early Eighties.

Part of the film’s enduring pleasure lies in its familiarity. Audiences had the sense that they had seen all of its set-ups, chases and action sequences somewhere else before. That’s because they had. Spielberg and his collaborators shamelessly borrowed ideas from elsewhere. The bravura opening, in which Indiana Jones ventures deep into the jungle and finds the booby-trapped temple, was inspired by a Donald Duck comic. The stunt in which Indiana Jones lowers himself under a lorry and lets himself be dragged along was taken from old westerns, with Hollywood’s greatest stuntman Yakima Canutt having performed similar feats underneath stagecoaches. Spielberg has openly acknowledged his debt to Cecil B de Mille’s The Greatest Show on Earth, one of the very first films he ever saw.

De Mille was notorious for his megalomania, a trait that Spielberg partly shared. There is a revealing moment in the “making of” documentary accompanying the film in which the director is distraught because he discovers he only has 2,000 snakes for an important scene. He tells his assistants that at least another 7,000 are needed. “His assistants nod as if they’ve been asked to find paper napkins but two days later, the pet shops of London and Antwerp are bereft of reptiles,” the narrator dryly notes.

In the documentary, Spielberg is also exposed as a bit of a tyrant, pushing star Karen Allen to scream louder and show more terror. “When I say more and more, you give me more but in increments of millimetres instead of feet,” he chastises her.

Certain elements rankle. You won’t find much sophistication or subtlety in Spielberg’s depiction of the Arab world. In particular, the Egyptian characters are grotesquely caricatured. Whether in the jungles of Peru, mountain top bars of Nepal or the hidden tombs and vaults outside Cairo, Indiana Jones treats anywhere he visits as his own adventure playground. The locals are there either to run after, run away from or, as happens most notoriously when he is confronted by the Arab swordsman, to shoot down dead.

Spielberg was so determined to crank up the tempo that he didn’t always pay attention to the nuances in Kasdan’s screenplay. “My feeling was that we should have edited a little of the chase sequences so that we’d have time to properly establish the characters,” the writer later commented. However, the pacing is one of the film’s main glories. Spielberg and Lucas, then in their thirties, were bursting with youthful exuberance.

The sequels were immensely popular too but, by the time Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull premiered at the Cannes Festival in 2008, there was a sense the franchise was stuttering. The fourth instalment was still very successful but was weighed down by a new self-consciousness. Ideas that had seemed spontaneous in 1981 were now looking laboured.

James Mangold is a distinguished filmmaker, but he is best known for dark, dramatic movies, not matinee-style adventure. Raiders of the Lost Ark had a magical innocence because Spielberg and Lucas were trying so hard to recapture the idealism of their own movie-going childhoods. It will be especially hard to emulate this if Spielberg, the original ringmaster, isn’t there to crack the whip.

James Bond and superhero franchises, however, have managed continually to re-invent themselves. If Indiana Jones 5 is a success, Indiana Jones 6 is bound to follow

The screenplay for the new movie has been written by Lawrence Kasdan’s son, Jonathan, who also worked on Solo: A Star Wars Story. His daunting challenge is to reinvigorate the franchise without seeming flip or cynical. Production designer Adam Stockhausen, who worked such wonders for director Wes Anderson on The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), will be responsible for the look of the film and is likely to come up with similarly eye-popping visual ideas.

It’s obviously absurd to worry that a project will be an anti-climax before it has even started shooting. The gap between The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) and the new Indiana Jones is shorter than that between Crystal Skull and The Last Crusade, released in 1989. Even so, getting the band back together isn’t always the best idea. The trouble with belated sequels is that everyone grows old and out of shape. Whether in comedies such as Dumb and Dumber To (released in 2014, 20 years after Dumb and Dumber) or in dramas like the leaden Texasville (1990), Peter Bogdanovich’s sequel to his 1971 classic The Last Picture Show, the magic dissipates as the years pass.

James Bond and superhero franchises, however, have managed continually to re-invent themselves. If Indiana Jones 5 is a success, Indiana Jones 6 is bound to follow. There have been other spin-offs already, of course. Lucas himself was heavily involved in the 1990s TV series, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. Nonetheless, reports that the film will “kick-start multiple spin-off” movies is dispiriting. They suggest that Indiana Jones, once the freshest movie character around, has now turned into just another Hollywood trademark or brand. His new adventures are being planned with marketing opportunities in mind rather than with giving audiences the white-knuckle ride that Raiders of the Lost Ark so memorably provided.

The next Indiana Jones film, as yet untitled, is due to be released in July 2022

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments